Acute Stress Disorder as a Predictor of Posttraumatic Stress Symptoms

Abstract

OBJECTIVE: Using the DSM-IV diagnostic criteria for acute stress disorder, the authors examined whether the acute psychological effects of being a bystander to violence involving mass shootings in an office building predicted later posttraumatic stress symptoms. METHOD: The participants in this study were 36 employees working in an office building where a gunman shot 14 persons (eight fatally). The acute stress symptoms were assessed within 8 days of the event, and posttraumatic stress symptoms of 32 employees were assessed 7 to 10 months later. RESULTS: According to the Stanford Acute Stress Reaction Questionnaire, 12 (33%) of the employees met criteria for the diagnosis of acute stress disorder. Acute stress symptoms were found to be an excellent predictor of the subjects' posttraumatic stress symptoms 7–10 months after the traumatic event. CONCLUSIONS: These results suggest not only that being a bystander to violence is highly stressful in the short run, but that acute stress reactions to such an event further predict later posttraumatic stress symptoms.

Acute stress disorder is a new psychiatric diagnosis in DSM-IV that includes a set of symptoms experienced by some individuals shortly after a traumatic event. To be diagnosed as suffering from acute stress disorder the individual must exhibit at least three dissociative symptoms along with at least one intrusion, avoidance, and hyperarousal symptom. In addition, the symptoms must cause clinically significant difficulties in functioning and persist 2–28 days. Also, the reaction must not be due to the ingestion of substances or to a general medical condition or be attributable to a brief psychotic disorder or a preexisting axis I or axis II disorder.

This diagnosis is based on a large body of research dating back to Lindemann's classic paper (1) in which he described survivors' immediate reactions to the Coconut Grove fire. Since Lindemann's observations there have been numerous studies that have reports of dissociative, avoidance, and hyperarousal symptoms shortly after traumatic experiences (2–10). The specific diagnostic criteria for acute stress disorder were based on empirical evidence from studies that systematically documented acute stress reactions in response to traumatic events (2–4, 7).

The scientific basis for the diagnostic category of acute stress disorder was also justified by research showing that dissociative reactions immediately after a traumatic experience predicted later posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) symptoms (2–4, 7, 11–14). These studies were conducted before the final definition of acute stress disorder and its inclusion in DSM-IV and, therefore, did not include a systematic assessment of all acute stress disorder symptoms and their relationship with later PTSD symptoms. To our knowledge, no published research has systematically examined the relationship between acute stress disorder and PTSD symptoms, despite the assumption stated in DSM-IV that acute stress disorder can lead to PTSD. Therefore, we conducted a study to examine the relationship between acute stress disorder symptoms and PTSD symptoms.

Along with documenting the relationship between acute stress disorder symptoms and PTSD symptoms, in the present study we examined this relationship within the context of two other factors, gender and degree of exposure to the traumatic event. Gender has been shown to be associated with acute stress reactions (15) and PTSD symptoms (16–19), with women reporting the most symptoms. Degree of exposure to the traumatic event has been found to be associated with the level of symptoms following a traumatic event (7, 8, 14, 19–26), although in one anecdotal study no such relationship was found (27).

The hypotheses in this study were as follows: 1) meeting all of the symptom criteria for acute stress disorder would predict subsequent PTSD symptoms, 2) women would be more likely than men to exhibit PTSD symptoms, and 3) degree of exposure to the threat would be positively associated with PTSD symptoms. Along with gender, other demographic variables (education and marital status) were included in the analyses in order to control for their contribution to the development of PTSD symptoms.

The traumatic incident examined was the shooting of persons by a gunman in an office building where the respondents in this study worked. Unfortunately, such events are not rare. In 1993, a thousand employees in the United States were murdered at their places of work (28). Research suggests that persons who are bystanders, such as other employees, are deeply affected by these events. Several studies have examined stress reactions to being a bystander to shootings (24, 29–31). These studies indicated that acute stress reactions to such an event are normal. Nevertheless, some individuals may exhibit more extreme reactions to the event, warranting a diagnosis of acute stress disorder in the immediate aftermath, and may later experience posttraumatic stress symptoms.

We conducted a study of employees working in an office building where a shooting spree occurred during the workday. We examined their acute stress reactions in the immediate aftermath of this event. Their posttraumatic stress symptoms were assessed 7 to 10 months later.

METHOD

The Traumatic Event

On the afternoon of Thursday, July 1, 1993, 14 persons were shot on two floors and in the stairwell of a high-rise office building at 101 California Street in San Francisco. Eight persons, including the gunman, were shot fatally. Many employees were trapped inside the building for hours while police officers tried to stop the gunman, and there were rumors that there were at least two gunmen on the loose. Within 8 days after the shootings, 36 employees from two firms on nearby floors of the building attended a crisis intervention session and completed questionnaires about their acute distress symptoms and other reactions.

Study Group

After obtaining permission from our institutional human subjects review committee to perform this study, we were granted permission from two firms to meet with their employees to offer a crisis intervention session and to seek their participation in this study. Before the intervention and data collection, the subjects were fully informed regarding the crisis intervention and the data collection. They were invited to participate in the intervention session and were told that their participation in the intervention in no way obligated them to participate in the study. The intervention took approximately 1 hour and consisted of inviting the employees to describe the thoughts and feelings they had had both during and after the traumatic event, providing a brief overview of common reactions to trauma as a way of normalizing their experience, providing suggestions for what they could do to help themselves integrate the experience and then move on in their lives, and describing how to determine whether they required professional help.

After the crisis intervention session, the study was introduced, the procedure of the study was fully explained, and the employees were again reminded that they were under no obligation to participate. Written informed consent was received, and the questionnaires were distributed; 36 employees completed the questionnaires. All worked in the office building where the shootings occurred; 26 worked in one firm and 10 worked in another. All questionnaires were completed within 8 days after the shootings. A follow-up assessment was mailed to the participants 7 months later, and follow-up mailings and phone calls were conducted to encourage willing participants to complete this follow-up assessment. Of the 36 persons who participated in the original assessment, 32 (89%) completed the follow-up assessment.

Measures

Demographic characteristics. The respondents provided demographic information in a self-report questionnaire. The variables assessed were sex, age, marital status, and years of education.

Ratings of the threatening event. An additive exposure scale assessed the degree of contact that the respondents had with the traumatic event. The types of exposure included being in the office building at the time of the shooting and seeing the S.W.A.T. (police tactical) team. None of the subjects saw the gunman or his victims. The respondents were asked to indicate whether they had experienced each of these forms of exposure to the event. Exposure was scored as 0 if the respondent was not in the building at the time, 1 if the respondent was in the building but did not see the S.W.A.T. team, and 2 if the respondent was in the building and saw the S.W.A.T. team.

The respondents were asked to rate how disturbing their experience with this event was, on a scale of 0–10, where 0 represented “not at all disturbing” and 10 indicated “extremely disturbing.”

Stanford Acute Stress Reaction Questionnaire. This self-report measure asks the respondent to indicate the frequency with which he or she experiences a variety of symptoms during or after a stressful event. Versions of this measure have been used in studies that have assessed acute reactions to an earthquake (2), witnessing an execution (4), and a firestorm (7). This version of the Stanford Acute Stress Reaction Questionnaire assessed four types of symptoms matching the criteria for a diagnosis of acute stress disorder: dissociation (nine items, e.g., “I experienced myself as though I were a stranger”); hyperarousal (five items, e.g., “I felt hypervigilant or on edge”); reexperiencing the traumatic event (six items, e.g., “I had repeated and unwanted memories of the shootings”); and avoidance of reminders of the traumatic event (two items, e.g., “I tried to avoid activities or situations that reminded me of the shootings”). Internal consistency for this group of subjects, based on Cronbach's alpha, was high overall (0.93) and also for the particular symptom subscales of the questionnaire (0.72–0.88).

Impact of Event Scale. The Impact of Event Scale (32) is a self-report measure assessing the degree of subjective distress experienced after a stressful life event. In this study, the Impact of Event Scale was used in the 7-month follow-up assessment as an additional measure of PTSD symptoms. Individuals were asked to rate the frequency with which they had had intrusive or avoidant experiences in the 7 days before assessment. Intrusive experiences include unwanted thoughts, feelings, or images of the trauma (e.g., “Pictures about it popped into my mind”). Avoidant experiences include having tried to avoid reminders of the trauma or to dull emotional reactions to it (e.g., “I stayed away from reminders of it”). Internal consistency (Cronbach's alpha) for this group was high overall (0.91) and for both subscales (intrusion=0.89, avoidance=0.88).

Davidson Trauma Scale. The Davidson Trauma Scale (33) was developed to assess each of the symptoms in DSM-IV needed for a diagnosis of PTSD. This instrument comprises 17 items inquiring about frequency and severity of PTSD symptoms within the past week; frequency is assessed on a 0–4-point scale in which 0 represents “not at all” and 4 indicates “every day,” and severity is assessed on a 0–4-point scale in which 0 represents “not at all distressing” and 4 means “extremely distressing.” This instrument is used to assess PTSD symptoms and has been validated with adult survivors of childhood sexual abuse (33), rape survivors, and Hurricane Andrew survivors (Davidson, unpublished manuscript). Its internal consistency is excellent; the Cronbach's alpha was 0.91 in a test with rape survivors. Its criterion validity was evidenced in the studies of both rape and hurricane survivors, in which the survivors diagnosed as having PTSD (with the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-III-R) had significantly higher mean scores than did the survivors not meeting the diagnostic criteria for PTSD. Also, this measure's concurrent validity is supported by strong correlations with the scores on the Impact of Event Scale of rape survivors and with the SCL-90 global severity scores, anxiety subscale scores, and depression subscale scores of hurricane survivors (Davidson, unpublished manuscript). Internal consistency for this study group was high (Cronbach's alpha=0.92). To yield a summary score on this measure, we tallied the number of symptoms experienced at least once in the past week (at least twice for recurrent symptoms) that were minimally to extremely distressing.

Data Analysis

Means, standard deviations, and frequencies were computed to summarize the distribution of values for each variable. To test the relationships between PTSD symptoms and the independent variables, we conducted multiple regression analysis to analyze PTSD symptoms (assessed as number of symptoms reported on the Davidson Trauma Scale and subscale scores on the intrusion and avoidance subscales of the Impact of Event Scale) by three blocks of independent variables, entered hierarchically. In the first block we used the stepwise forward procedure with the variables of sex, age, years of education, and marital status to examine for preexisting demographic differences that could account for the variance in posttraumatic stress symptoms. In the second block we again used the stepwise forward procedure and entered the degree of exposure to the threatening event, and in the third block we entered whether the respondent met the symptom criteria for an acute stress disorder diagnosis. Using this analytic strategy, we were able to examine whether any significant variance in PTSD symptoms was associated with demographic and exposure variables before we analyzed the variance in PTSD symptoms associated with meeting the criteria for acute stress disorder, the variable of most interest. To analyze the relationships between specific symptoms of acute stress disorder and PTSD symptoms, we computed Pearson's product moment correlations between the four types of acute stress disorder symptoms (dissociation, hyperarousal, intrusion, and avoidance) and the three measures of PTSD symptoms.

RESULTS

Univariate Statistics on Independent and Dependent Variables

Of the 36 employees, 24 (67%) were women. The employees ranged in age from 22 to 74 years (mean=33.2, SD=10.4) and ranged in education from high school diploma to graduate school, with 80% having completed college (28 of 35). Their marital status distribution (N=35) was as follows: single, 54% (N=19); married, 34% (N=12); and divorced, 11% (N=4).

The majority of the respondents (69%, N=25) were in the building at the time of the shooting and saw the S.W.A.T. team, 17% of the respondents (N=6) were trapped in the building but did not see the S.W.A.T. team, and 14% (N=5) neither were trapped in the building nor saw the S.W.A.T. team. None of our subjects actually saw the gunman or the victims.

When asked how disturbing the event was, the respondents gave the event a mean rating of 6.9 (SD=2.6). This is almost 2 points above 5, which is labeled “moderately disturbing.”

Of the 36 subjects, 12 (33%) met the criteria for the acute stress disorder diagnosis. The respondents experienced a mean of 2.0 dissociative symptoms (SD=1.5) out of a possible 5 symptoms, a mean of 1.3 symptoms of reexperiencing the traumatic event (SD=1.3) out of 5, a mean of 2.7 symptoms of anxiety and hyperarousal (SD=1.7) out of 5, and a mean of 1.0 of 2 possible symptoms of avoiding reminders of the event (SD=0.9).

At the 7–10-month follow-up assessment, 32 of the 36 respondents completed the questionnaires, although one of these respondents did not complete the Davidson Trauma Scale. The respondents' mean frequency of PTSD symptoms reported on the Davidson Trauma Scale was 2.5 (SD=3.9) out of a possible 4. Also, the respondents' mean score at follow-up on the Impact of Event Scale intrusion subscale was 7.9 (SD=7.8); their mean score on the avoidance subscale was 8.1 (SD=9.3).

Relation of PTSD Symptoms to Acute Stress Disorder, Trauma Exposure, and Demographic Characteristics

The overall regression models were significant for predicting overall posttraumatic stress frequency scores on the Davidson Trauma Scale (F=5.86, df=1,27, p<0.05, adjusted R2=0.15), frequency of intrusive symptoms as indicated by the intrusion subscale of the Impact of Event Scale (F=30.38, df=1,28, p<0.0001, adjusted R2=0.50), and frequency of avoidance symptoms as indicated by the avoidance subscale of the Impact of Event Scale (F=21.25, df=1,28, p<0.0001, adjusted R2=0.41). The results supported the hypothesis that PTSD symptoms were associated with meeting all of the symptom criteria for acute stress disorder; however, PTSD symptoms were not significantly related to exposure to the traumatic event, contrary to our hypothesis. None of the demographic variables was significantly related to any of the measures of PTSD symptoms, thereby providing no support for the hypothesis that women would be more likely to show PTSD symptoms. Meeting the criteria for the acute stress disorder diagnosis was significantly related to the overall posttraumatic stress frequency score on the Davidson Trauma Scale (B=3.39, SE=1.40, t=2.42, df=1,27, p<0.05), to frequency of intrusive symptoms as indicated by the intrusion subscale of the Impact of Event Scale (B=11.79, SE=2.13, t=5.51, df=1,28, p<0.0001), and to frequency of avoidance symptoms as indicated by the avoidance subscale of the Impact of Event Scale (B=12.70, SE=2.76, t=4.61, df=1,28, p<0.0001).

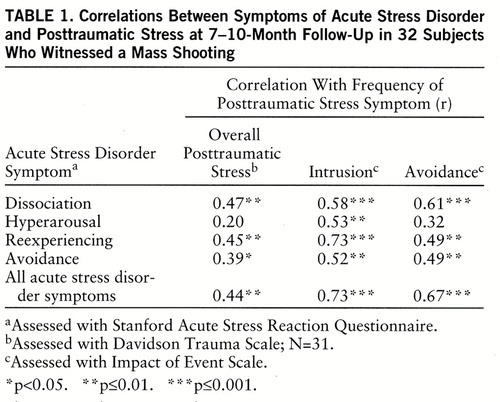

Relation of Acute Stress Disorder to PTSD Symptoms

Table 1 shows the Pearson's product moment correlation coefficients for the association between acute stress disorder symptoms and PTSD symptoms in response to the shootings. All but two of the 15 relationships were statistically significant and in the positive direction. This showed that three of the four symptoms included in the acute stress disorder diagnosis (dissociation, reexperiencing, and avoidance) and the overall diagnosis were strongly related to the frequency of experiencing posttraumatic stress symptoms. Hyperarousal was found to be positively correlated with intrusion, although it was not significantly correlated with overall PTSD or avoidance.

DISCUSSION

This study provides evidence that acute stress disorder predicts PTSD. As hypothesized, individuals who met all of the symptom criteria for acute stress disorder were more likely to report PTSD symptoms 7 to 10 months later. However, neither extent of exposure to the traumatic event nor gender was found to predict PTSD symptoms. An exploratory analysis showed that three of the four symptoms included in the acute stress disorder diagnosis (dissociation, reexperiencing the traumatic event, and avoidance) and the overall diagnosis of acute stress disorder were strongly related to the frequency of experiencing PTSD symptoms. Of these acute stress disorder symptoms, dissociation in response to the trauma was found to be one of the strongest predictors of PTSD symptoms 7 to 10 months later. This suggests that dissociation may be a fundamental symptom of acute stress disorder. Hyperarousal was found to predict intrusion at follow-up but not avoidance or overall posttraumatic stress. This suggests that hyperarousal might be less important as a predictor of PTSD.

There are several limitations to this study. The main limitation is that the subjects were not formally diagnosed by a clinician as having either acute stress disorder or PTSD. Instead, the diagnoses were based on paper-and-pencil measures that were designed to assess some but not all diagnostic criteria. The measures did not assess whether the symptoms caused clinically significant distress or impairment in functioning, which is necessary for a formal diagnosis of acute stress disorder or PTSD. Also, other diagnoses that may have accounted for the acute stress disorder symptoms were not ruled out.

The study group in this study was small, the subjects were not randomly selected, and there was no control group. The subjects were recruited from two nearby floors and consisted of individuals who had agreed to participate after having received a crisis intervention session. A larger group of subjects randomly selected from all floors would have been better. It would have given us greater power to test our hypotheses, ensured varying degrees of exposure, and circumvented the problem of having subjects who were self-selected on the basis of their desire for crisis intervention. Having a control group that experienced the traumatic event and did not receive an intervention would have enabled us to also examine the relationship between acute stress disorder and PTSD symptoms when there is no intervention.

Our clinical impression was that the debriefing was experienced as beneficial. The participants appeared relieved to be able to share their experiences with others and to learn that they were not alone in their reactions. Several commented on the helpfulness of the intervention. Thus, to the extent that the intervention was effective, the relationship between acute stress disorder and PTSD symptoms may be underestimated.

In this study we did not find a relationship between exposure and PTSD symptoms, and this negative finding might be due to the small number of subjects or to a restricted range of exposure. Additionally, it may be because our measure of exposure lacked sensitivity. In addition, the small number of subjects precluded examining the role of acute stress disorder relative to other predictors of PTSD, such as stressful life events (11).

Notwithstanding these limitations, the results suggest that when individuals experience a traumatic event and suffer from acute stress disorder, they may also be vulnerable to developing PTSD and might benefit from immediate treatment (34–36). Given the role of dissociation in acute reactions to a traumatic event, affected individuals are likely to distance themselves from the event through amnesia, depersonalization, derealization, or other means, thereby avoiding the “grief work” necessary to working through the traumatic experience and putting it into perspective (1, 37, 38). Sufferers of acute stress disorder are likely to split off the event from their experience if untreated.

Thus, individuals who have experienced a traumatic event should be given the opportunity to process it. The goals should include normalizing the reactions to the trauma, providing a safe environment that enables the expression of strong feelings, enhancing understanding, and making meaning out of the experience (38, 39).

Another implication of this study is that when individuals are not directly the targets of violence but experience only the threat of violence, they too are vulnerable to developing acute stress disorder and PTSD. A full one-third of the individuals in this study met the symptom criteria for acute stress disorder and were more likely to develop PTSD symptoms. These were individuals who never actually saw the gunman, although several individuals stated that they saw a member of the S.W.A.T. team and momentarily thought it was the gunman. Nevertheless, there was only the threat of violence, and it was sufficient for development of symptoms.

The results of this study suggest that individuals who are exposed to violence may develop acute stress disorder as a precursor to PTSD symptoms. Given the increasingly violent nature of our society, this puts substantial numbers of individuals at risk of developing psychological problems. Given the predictive value of acute stress disorder symptoms, they provide an opportunity for early case identification and intervention to prevent the development of PTSD.

|

Received March 25, 1996; revisions received Feb. 19 and July 11, 1997; accepted Sept. 18, 1997. From the Department of Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences, Stanford University School of Medicine, and the Department of Psychiatry, University of California, Davis. Address reprint requests to Dr. Classen, Department of Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences, Stanford University School of Medicine, Stanford, CA 94305-5718; [email protected] (e-mail). Supported by grants from the John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation and the American Psychiatric Association. The authors thank Ami Atkinson, John Mori, and the persons who participated in the study.

1 Lindemann E: Symptomatology and management of acute grief. Am J Psychiatry 1944; 101:141–148Link, Google Scholar

2 Carde¤a E, Spiegel D: Dissociative reactions to the San Francisco Bay Area earthquake of 1989. Am J Psychiatry 1993; 150:474–478Link, Google Scholar

3 Feinstein A: Posttraumatic stress disorder: a descriptive study supporting DSM-III-R criteria. Am J Psychiatry 1989; 146:665–666Link, Google Scholar

4 Freinkel A, Koopman C, Spiegel D: Dissociative symptoms in media eyewitnesses of an execution. Am J Psychiatry 1994; 151:1335–1339Link, Google Scholar

5 Hagstrom R: The acute psychological impact on survivors following a train accident. J Trauma Stress 1995; 8:391–402Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

6 Holen A: The North Sea oil rig disaster, in International Handbook of Traumatic Stress Syndromes. Edited by Wilson J, Ra~phael B. New York, Plenum, 1993, pp 471–478Google Scholar

7 Koopman C, Classen C, Spiegel D: Predictors of posttraumatic stress symptoms among survivors of the Oakland/Berkeley, Calif, firestorm. Am J Psychiatry 1994; 151:888–894Link, Google Scholar

8 Nolen-Hoeksema S, Morrow J: A prospective study of depression and posttraumatic stress symptoms after a natural disaster: the 1989 Loma Prieta earthquake. J Pers Soc Psychol 1991; 61:115–121Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

9 Shalev AY, Peri T, Canetti L, Schreiber S: Predictors of PTSD in injured trauma survivors: a prospective study. Am J Psychiatry 1996; 153:219–225Link, Google Scholar

10 Ursano RJ, Fullerton CS, Kao TC, Bhartiya VR: Longitudinal assessment of posttraumatic stress disorder and depression after exposure to traumatic death. J Nerv Ment Dis 1995; 183:36–42Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

11 Bremner JD, Southwick SM, Johnson DR, Yehuda R, Charney DS: Childhood physical abuse and combat-related posttraumatic stress disorder in Vietnam veterans. Am J Psychiatry 1993; 150:235–239Link, Google Scholar

12 Marmar CR, Weiss DS, Schlenger WE, Fairbank JA, Jordan BK, Kulka RA, Hough RL: Peritraumatic dissociation and posttraumatic stress in male Vietnam theater veterans. Am J Psychiatry 1994; 151:902–907Link, Google Scholar

13 McFarlane AC: Posttraumatic morbidity of a disaster: a study of cases presenting for psychiatric treatment. J Nerv Ment Dis 1986; 174:4–14Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

14 Solomon Z, Mikulincer M, Benbenishty R: Combat stress reaction: clinical manifestations and correlates. Military Psychol 1989; 1:35–47Crossref, Google Scholar

15 Palinkas LA, Russell J, Downs MA, Petterson JS: Ethnic differences in stress, coping, and depressive symptoms after the Exxon Valdez oil spill. J Nerv Ment Dis 1992; 180:287–295Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

16 Breslau N, Davis GC: Posttraumatic stress disorder in an urban population of young adults: risk factors for chronicity. Am J Psychiatry 1992; 149:671–675Link, Google Scholar

17 North CS, Smith EM, Spitznagel EL: Posttraumatic stress disorder in survivors of a mass shooting. Am J Psychiatry 1994; 151:82–88Link, Google Scholar

18 Raphael B, Meldrum L: The evolution of mental health responses and research in Australian disasters. J Trauma Stress 1993; 6:65–89Crossref, Google Scholar

19 Hardin SB, Weinrich M, Weinrich S, Hardin TL, Garrison C: Psychological distress of adolescents exposed to Hurricane Hugo. J Trauma Stress 1994; 7:427–440Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

20 Palinkas LA, Petterson JS, Russell J, Downs MA: Community patterns of psychiatric disorders after the Exxon Valdez oil spill. Am J Psychiatry 1993; 150:1517–1523Link, Google Scholar

21 Bowler RM, Mergler D, Huel G, Cone JE: Psychological, psychosocial, and psychophysiological sequelae in a community affected by a railroad chemical disaster. J Trauma Stress 1994; 7:601–624Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

22 Carlson EB, Rosser-Hogan R: Trauma experiences, posttraumatic stress, dissociation, and depression in Cambodian refugees. Am J Psychiatry 1991; 148:1548–1551Link, Google Scholar

23 Mueser KT, Butler RW: Auditory hallucinations in combat-related chronic posttraumatic stress disorder. Am J Psychiatry 1987; 144:299–302Link, Google Scholar

24 Pynoos RS, Frederick C, Nader K, Arroyo W, Steinberg A, Eth S, Nunez F, Fairbanks L: Life threat and posttraumatic stress in school-age children. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1987; 44:1057–1063Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

25 Sanders B, Giolas MH: Dissociation and childhood trauma in psychologically disturbed adolescents. Am J Psychiatry 1991; 148:50–54Link, Google Scholar

26 Wood JM, Bootzin RR, Rosenhan D, Nolen-Hoeksema S, Jourden F: Effects of the 1989 San Francisco earthquake on frequency and content of nightmares. J Abnorm Psychol 1992; 101:219–224Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

27 Hillman RG: The psychopathology of being held hostage. Am J Psychiatry 1981; 138:1193–1197Link, Google Scholar

28 Martin S: Workplace is no longer a haven from violence. APA Monitor, October 1994, p 29Google Scholar

29 North CS, Smith EM, McCool RE, Shea JM: Short-term psychopathology in eyewitnesses to mass murder. Hosp Community Psychiatry 1989; 40:1293–1295Abstract, Google Scholar

30 Creamer M, Burgess P, Pattison P: Reaction to trauma: a cognitive processing model. J Abnorm Psychol 1992; 101:452–459Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

31 Sewell JD: Traumatic stress of multiple murder investigations. J Trauma Stress 1993; 6:103–118Crossref, Google Scholar

32 Horowitz MJ, Wilner N, Alvarez W: Impact of Event Scale: a measure of subjective stress. Psychosom Med 1979; 41:209–218Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

33 Zlotnick C, Davidson J, Shea MT, Perlstein T: The validation of the Davidson Trauma Scale in a sample of survivors of childhood sexual abuse. J Nerv Ment Dis 1996; 184:255–257Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

34 Hoiberg A, McCaughey BG: The traumatic aftereffects of collision at sea. Am J Psychiatry 1984; 141:70–73Link, Google Scholar

35 Manton M, Talbot A: Crisis intervention after an armed hold-up: guidelines for counsellors. J Trauma Stress 1990; 3:507–522Crossref, Google Scholar

36 Spiegel D, Classen C: Acute stress disorder, in Treatment of Psychiatric Disorders, 2nd ed, vol 2. Edited by Gabbard GO. Washington, DC, American Psychiatric Press, 1995, pp 1521–1535Google Scholar

37 Spiegel D: Vietnam grief work using hypnosis. Am J Clin Hypn 1981; 24:33–40Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

38 Spiegel D: The use of hypnosis in the treatment of PTSD. Psychiatry Med 1992; 10:21–30Google Scholar

39 Embry CK: Psychotherapeutic interventions in chronic posttraumatic stress disorder, in Posttraumatic Stress Disorder: Etiology, Phenomenology, and Treatment. Edited by Wolf ME, Mosniam AD. Washington, DC, American Psychiatric Press, 1990, pp 226–236Google Scholar