Psychiatric Disorder Onset and First Treatment Contact in the United States and Ontario

Abstract

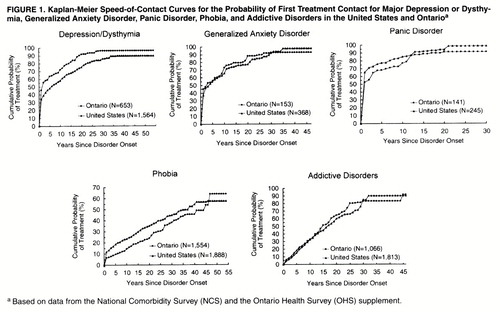

Objective:The authors describe the timing of the first treatment contact following new-onset DSM-III-R mood, anxiety, and addictive disorders in community samples from the United States and Ontario, Canada, before and after passage of the Ontario Health Insurance Plan.Method:The authors drew data from the National Comorbidity Survey (NCS) (N=8,098) and the mental health supplement to the Ontario Health Survey (OHS) (N=9,953). They assessed psychiatric disorders with a modified version of the Composite International Diagnostic Interview; they also assessed retrospectively age at disorder onset and first treatment contact. They used the Kaplan-Meier method to generate time-to-treatment curves and survival analysis to compare time-to-treatment intervals across the two surveys.Results:The overall time-to-treatment curves revealed substantial differences between disorders that were consistent across the two surveys. In both surveys, panic disorder had the highest probability of first-year treatment (NCS, 65.6%; OHS supplement, 52.6%), while phobia (NCS, 12.0%; OHS supplement: 6.5%) and addictive disorders (NCS, 6.4%; OHS supplement, 4.2%) had the lowest in both surveys. Retrospective subgroup analysis suggests that before the passage of the Ontario public insurance plan, the likelihood of receiving treatment in the year of disorder onset was greater in Ontario than in the United States but that this relationship reversed following passage of the Ontario plan. During this period, the authors observed no significant between-country differences in the probability of prompt treatment of adults with 12 or fewer years of education. Conclusions:These results challenge the assumption that the universal health insurance plan in Ontario promotes greater access to mental health services than is available in the United States for vulnerable groups. Marked differences between disorders in the speed to first treatment suggest that in both countries, clinical factors play an important role in the timing of the initial decision to seek treatment. Am J Psychiatry 1998; 155: 1415-1422

There are often long delays between the onset of a mental disorder and the time that it is first brought to the attention of a health care professional. In the United States, it is not uncommon for people with substance use disorders or phobias to wait a number of years before ever discussing their problems with a health care professional (1). An important challenge facing the U.S. mental health system is to extend treatment in a timely manner to people with well-defined psychiatric disorders.

Research on treatment seeking for mental health problems has tended to focus on the current episode of illness. In prevalent cases, the decision to seek mental health care may be determined or modified by clinical (2-4), demographic (5-8), attitudinal (9), cultural (10, 11), social (12-14), geographic (15, 16), and economic (17-19) factors. Much less is known, however, about the factors that influence the speed to initial treatment for new-onset or incident cases of psychiatric disorder. People who have not previously received mental health services may be particularly reluctant to recognize their need for treatment and establish treatment contact (20). Long lag periods between disorder onset and first professional-treatment contact remain an important source of unmet need for mental health care.

U.S. health policy analysts commonly look to the public health insurance system of Canada as a model for reform (21, 22). Some believe that the Canadian system, with its single-source financing, strong public mandate to treat psychiatric disorders, and universal coverage, provides enhanced access to mental health services (23). A survey conducted following the enactment of the Ontario Health Insurance Plan found that most psychiatrists believed that the plan had benefited their patients (24). A later survey, however, indicates that Canadian patients tend to experience longer waits for certain psychiatric services than do their U.S. counterparts (25).

The Canadian health care system relies heavily upon services provided by primary care physicians (26). Access to mental health specialists through primary care physicians is the preferred practice pattern. In Ontario, physicians are the sole providers of publicly funded fee-for-service mental health services. Although some psychologists, social workers, and other nonphysician mental health specialists receive salaries at public health centers, they are not qualified to receive public fee-for-service reimbursement (27).

It is widely believed that the poor have greater access to care in Canada than in the United States. Primary care physicians in Canada rarely report that poor people have problems with access to care (28). In the United States, by contrast, primary care physicians indicate that barriers to health care access pose common and serious problems for the poor and medically indigent (28).

How do the patterns of treatment contact following the initial onset of psychiatric disorders compare in the United States and Ontario? Does universal access to care speed the time to initial treatment contact? More specifically, does the universal access to care available in Ontario accelerate the time to first treatment contact for socioeconomically disadvantaged people, such as those with less formal education, who have well-defined psychiatric disorders?

We address these and related issues through an analysis of the time to initial professional contact following onset of psychiatric disorder in representative samples from the United States (29) and Ontario (30). Between-country comparisons are provided of first-year and cumulative lifetime probabilities of professional contact for five types of psychiatric disorder: depression, panic, generalized anxiety, phobia, and addictive disorders.

Before conducting these analyses, we hypothesized that the time to first professional contact would be shorter in Ontario than in the United States. We expected that the universal mental health insurance available in Ontario would facilitate prompt contact with health professionals by lowering economic barriers to service access. We further hypothesized that this difference would be evident only after the passage of the Ontario Health Insurance Plan in 1966 and that it would be most pronounced among adults with no formal education beyond high school, the education level we selected as a marker of low socioeconomic status.

METHOD

Samples

Data were drawn from two household surveys conducted in 1990 that included identical questions to assess symptoms and service use: the U.S. National Comorbidity Survey (NCS) (29) and the mental health supplement to the Ontario Health Survey (OHS) (30).

The NCS is based on a national probability sample of persons aged 15 to 54 years in the noninstitutionalized U.S. civilian population. The response rate was 82.4%; a total of 8,098 interviews were completed. The data were weighted for differential probabilities of selection and nonresponse. In addition, a weight was included to adjust the sample to approximate the cross-classification of the population distribution on a range of sociodemographic characteristics.

The mental health supplement to the OHS was administered to a follow-up sample of 9,953 respondents randomly selected from households that had participated in the OHS. The response rate was 88.1% to the OHS, 76.5% to the supplement, and 67.4% overall. To maintain comparability with the NCS, we limited analysis of the OHS supplement to respondents from 15 to 54 years of age.

Diagnostic Assessment

Mental disorder diagnoses were derived from a modified version of the Composite International Diagnostic Interview (31), a structured interview designed for use by nonclinicians. The diagnoses include DSM-III-R major depressive episode with impairment or dysthymia with impairment (depressive disorder), panic disorder, generalized anxiety disorder, phobias (simple, social, or agoraphobia with or without panic), and addictive disorders (alcohol or drug abuse or dependence).

World Health Organization field trials (32, (33) and NCS clinical reappraisal studies (34-(36) have documented acceptable reliability and validity of all these diagnoses.

Treatment Contact

Following the diagnostic questions for each of the five disorder groups, we asked NCS and OHS supplement respondents whether they ever told a physician (other than a psychiatrist), a mental health specialist (psychiatrist, psychologist, or social worker), or any other professional about the problems discussed in that section of the interview. We defined first treatment contact as the earliest age the respondent reported telling any of the three groups of professionals about the given disorder.

Predictor Variables

Previous analyses (1) demonstrated that age at onset and age cohort predicted first treatment contact in the NCS. We coded age at disorder onset as a series of categories: ages 0–12, 13–19, 20–29, and 30 years or older. We defined age cohort as the respondent’s age (15–24, 25–34, 35–44, and 45–54 years) at survey interview.

We created a dichotomous variable to define whether the disorder onset preceded (before 1966) or followed (1966 and later) the enactment of the Ontario Health Insurance Plan. For respondents who were at least 19 years of age at disorder onset, we created a dichotomous variable to index whether they had completed 12 or fewer years or more than 12 years of education at the time of interview.

Analysis Procedures

We used the Kaplan-Meier method (37) to generate time-to-treatment curves for each disorder in each survey. We used survival analysis (38) to study time to treatment within disorder and across survey. We treated country, age cohort, age at onset, and level of education as time-invariant predictors; we treated number of years since disorder onset as a time-varying covariate. We estimated standard errors of parameter in the survival models in tables 1 and 2 by using the jackknife repeated replications method (39); we estimated those in tables 3 and 4 with simple random sampling because of the smaller subgroup size. The jackknife method is a resampling approach often used with complex sample surveys: it involves dividing the total sample into subsamples or replicates, dropping out one replicate while doubling the complementary replicate, and repeating this process until all strata are included. There are 42 resamplings clusters in the NCS and 72 in the OHS supplement. Variance estimates are then derived from replicate statistics, thereby producing estimates that account for the complex sample design.

Earlier analyses of the NCS revealed that other basic demographic characteristics (e.g., sex, race, and marital status) did not generally have significant main effects on time to first treatment (1). Among respondents with depression/dysthymia, for example, the odds of receiving treatment in the year of disorder onset were not significantly different for female and male respondents (NCS: 1.3, N=1,030, p=0.10; OHS supplement: 1.3, N=636, p=0.20).

RESULTS

Cumulative Lifetime Probability of Treatment Contact

The five graphs in figure 1 show Kaplan-Meier estimates by disorder of the cumulative probability of any treatment contact in each survey. We used logistic regression to examine the effect of country on speed to treatment for each disorder group. The speed to treatment was significantly greater in the NCS than in the OHS supplement for phobia (χ2=19.5, df=1, p<0.0001), while the reverse was true for depression/dysthymia (χ2=14.2, df=1, p<0.001) and addictive disorders (χ2=3.9, df=1, p<0.05).

The pattern of treatment contact for panic disorder in both surveys was distinguished from the other disorders by its high probability of contact in the year of disorder onset (NCS, 65.6%; OHS supplement, 52.6%). By contrast, phobia (NCS, 12.0%; OHS supplement, 6.5%) and addictive disorders (NCS, 6.4%; OHS supplement, 4.2%) had the lowest probabilities of first-year treatment contact (figure 1).

Effects of Age at Onset and Cohort on Treatment

Table 1 presents the effects of age at onset and birth cohort on treatment contact stratified by country in the year of disorder onset. In both countries, there is a powerful inverse effect of age at disorder onset on treatment contact in the year of disorder onset and thereafter. For example, NCS respondents with a first onset of depressive disorder between the ages of 30 and 54 years were 13.8 times more likely than those with childhood onsets (0–12 years of age) to receive treatment during the year of disorder onset. Similarly, the OHS supplement respondents who first developed a depressive disorder between the ages of 30 and 54 years were 14.9 times more likely to receive treatment within 1 year of the disorder onset than were their counterparts with childhood onsets. In both surveys, people in the most recent birth cohort with phobia or addictive disorders had a significantly greater likelihood of making treatment contact in the year of disorder onset than did people in the earliest cohort with these disorders. For depressive disorders, phobia, and addictive disorders, there were also significant birth cohort effects on treatment contact in the years following disorder onset (table 2).

Effects of Provincial Health Insurance

In an effort to determine whether the U.S.-Ontario difference changed after passage of the Ontario Health Insurance Plan, we used subgroup analysis to examine retrospective reports of speed of initial treatment contact 1) before 1966 (when the plan was passed) and 2) from 1966 to the present. In the years before passage of the Ontario Health Insurance Plan, the OHS supplement respondents with a depressive disorder or generalized anxiety disorder were significantly more likely than NCS respondents to report treatment within 1 year of disorder onset when we controlled for age at onset and cohort (table 3). However, Ontario’s comparative advantage was lost following the implementation of the health insurance plan.

In the years following enactment of the Ontario Health Insurance Plan, the OHS supplement respondents with phobias, addictive disorders, and panic disorder were significantly less likely than NCS respondents with these disorders to receive treatment within 1 year of disorder onset (table 3). For four out of the five disorders examined, there was also a continuing trend toward decreased probability of treatment for OHS supplement respondents relative to NCS respondents. This trend achieved significance for phobias (table 4).

Adults With 12 or Fewer Years of Education

We examined treatment contact during the year of disorder onset for adults with 12 or fewer years of formal education, controlling for age at onset and birth cohort. Under the Ontario Health Insurance Plan, there were no significant between-country differences in the likelihood of first-year treatment contact for this subgroup. The odds ratios for OHS supplement respondents relative to NCS respondents were depression/dysthymia, 2.8 (N=45); generalized anxiety disorder, 0.2 (N=18); phobia, 1.3 (N=37); and addictive disorders, 0.9 (N=36). The country factor was not retained in the model for panic disorder.

During the years preceding the Ontario insurance plan, the OHS supplement respondents with 12 or fewer years of education and depression/dysthymia (odds ratio=1.7, N=597, p<0.05) or a phobia (odds ratio=2.4, N=244, p<0.05) were significantly more likely than NCS respondents to receive treatment in the year of disorder onset when we controlled for age at onset and age cohort. During this period, there was not a significant between-country difference in the likelihood of first-year treatment contact for generalized anxiety disorder (odds ratio=1.5, N=186), panic disorder (odds ratio=0.6, N=133), or addictive disorders (odds ratio=1.0, N=489) among respondents with 12 or fewer years of education.

DISCUSSION

The current findings are limited by several methodological considerations. First, the timing between the onsets of the disorders and their initial treatment is based on long and uncertain periods of recall. Second, differences in immigration patterns to Ontario and the United States may have biased the results. If, for example, a large number of respondents arrived in Ontario from countries with poorly developed mental health systems after they had experienced their first illness episode, this would lead to a misrepresentation of treatment patterns under Ontario Health Insurance Plan coverage. Third, self-reported education is a relatively crude measure of socioeconomic status. A more sensitive measure such as current personal or family income, employment status, or insurance status might have yielded different results. Unfortunately, none of these measures was available for the full recall period. However, education attainment is a widely recognized determinant of occupational achievement (40) and financial security (41). Fourth, the Canadian data are limited to Ontario and may not generalize to the other Canadian provinces. Fifth, we have no information concerning the depth, quality, or effectiveness of services provided. Sixth, we selected an alpha level of 0.05 to highlight contrasts between health care-seeking patterns in the two surveyed populations. Given the relatively large number of comparisons, this threshold level risks type I error.

Within the context of these limitations, the results suggest that the time period separating psychiatric disorder onset from first treatment contact in the United States is not dramatically different from that in Ontario, Canada. For the five types of disorder examined, there were only modest overall between-country differences in the proportion of individuals who established treatment contact within 1 year of disorder onset or the proportion who went on to receive treatment at some later point. In both countries, long delays in initial treatment contact were especially common for addictive disorders and phobias.

More consistent between-country differences in treatment patterns emerged when we stratified the analyses by period and controlled for age at disorder onset and age cohort. During the period following the passage of the Ontario Health Insurance Plan, the probability of receiving treatment in the year of disorder onset was significantly greater in the United States than Ontario for three of five disorders examined.

Previous research indicates that the probability of recent service use is higher in the United States than Ontario for persons with lower levels of service need as defined by one rather than two or more psychiatric disorders (42). The current findings suggest that there is a trend toward shorter delays in time to treatment in the United States than Ontario for some more severe (e.g., panic disorder and addictive disorders) as well as less severe (e.g., phobia) disorders. Further research is needed to tease apart Ontario-United States comparisons in treatment delays for subgroups with multiple mental disorders.

Among people with 12 or fewer years of formal education, we found no significant between-country differences in the likelihood of receiving treatment in the year of disorder onset. This finding challenges the view that the universal public health insurance plan in Ontario, with its reduced financial barriers to care, provides greater access than the U.S. system to mental health services for socioeconomically vulnerable groups.

In the Canadian health system, there is tight control over the supply of specialized services. Canadian public policies strictly limit medical school enrollment and physician subspecialization (26). Reimbursement policies discourage direct access to psychiatrists (43) and restrict mental health services delivered by nonphysicians (27). In Ontario, expanded coverage for mental health services is balanced by close control over the supply of these services. In this regard, the Canadian system resembles evolving prepaid systems of care in the United States that seek to contain costs through managing the supply of services (44). Firm control over the supply of health services has contributed to lower total per capita health expenditures in Canada than the United States (45).

The expanding availability of third-party coverage for mental health services in the United States may also help explain the trend toward shorter delays in initial treatment contact in the United States relative to Ontario. The passage of Medicare and Medicaid legislation in 1965 and the subsequent growth of private mental insurance markets in the United States (46) provided an infusion of new funds to pay for mental health services. Unfortunately, it is not possible with the current data to desegregate the relative contribution of secular changes in the financing of mental health care in the United States from concurrent changes in Canada.

Until the early 1990s, fee-for-service care dominated outpatient mental health service delivery in the United States. During this period, consumers of mental health services in the United States had variable first-dollar coverage and were likely to incur higher out-of-pocket expenses than their counterparts covered by the Ontario plan. However, the price patients pay for outpatient mental health care may have a greater impact on the number of visits and total mental health expenditures than on the number of users (47). The initial decision to discuss a mental health problem with a health professional may turn more on clinical than economic considerations.

The marked variation in the time-to-treatment curves across disorders suggests that disorder-specific factors are important in early help-seeking processes. In both countries, for example, panic disorder had the highest rate of treatment contact in the year of disorder onset. The abrupt, intense, unexpected, and often frightening nature of an unheralded panic attack may drive individuals to seek professional help. By contrast, the relatively low level of disability associated with phobias and the denial and insight deficits that commonly occur in addictive disorders help explain the longer delays in treatment contact for these disorders in both countries. As Mechanic has noted, the salience, frequency, and persistence of symptoms—as well as the degree to which they disrupt daily activities or are perceived to threaten general health—are powerful determinants of health care seeking (48).

The current findings replicate in Canada earlier NCS analyses which demonstrated that the probability of treatment contact is inversely related to age at disorder onset and has increased in recent cohorts (1). In both countries, children may experience longer delays in receiving treatment because of their dependence upon adults to initiate a referral. The cohort effects may reflect a shared evolution in public attitudes and cultural assumptions concerning the importance of recognizing and treating mental illness as well as expanding third-party reimbursement to treat these conditions.

Our findings indicate that the availability of universal public mental health insurance in Ontario did not correspond with increased access to mental health services relative to the United States. On the contrary, the creation of the Ontario Health Insurance Plan coincided with a trend toward longer delays in mental health treatment in Canada than in the United States. This indicates that universal health care does not guarantee earlier recognition and treatment of common mental disorders. At the same time, however, the findings may tell us less about universal health care in general than about how it was defined and implemented in Ontario. An important challenge ahead lies in determining the extent to which prolonged delays in receiving treatment affect the course and outcome of the common mental disorders.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The National Comorbidity Survey (NCS) is a collaborative epidemiologic investigation of the prevalences, causes, and consequences of psychiatric morbidity and comorbidity in the United States.

Collaborating NCS sites and investigators are the Addiction Research Foundation (Robin Room); Duke University Medical Center (Dan Blazer, Marvin Swartz); Harvard Medical School (Richard Frank, Ronald Kessler); Johns Hopkins University (James Anthony, William Eaton, Philip Leaf); the Max Planck Institute of Psychiatry Clinical Institute (Hans-Ulrich Wittchen); the Medical College of Virginia (Kenneth Kendler); the University of Miami (R. Jay Turner); the University of Michigan (Lloyd Johnston, Roderick Little); New York University (Patrick Shrout); State University of New York at Stony Brook (Evelyn Bromet); and Washington University School of Medicine (Linda Cottler, Andrew Heath). A complete list of NCS publications along with abstracts, study documentation, interview schedules, and the raw NCS public use data files can be obtained directly from the NCS home page on the World Wide Web (http://www.hcp.med.harvard.edu/ncs/).

Received Aug. 5, 1997; revisions received Nov. 14, 1997, and Jan. 20, 1998; accepted Feb. 9, 1998. From the Department of Psychiatry, College of Physicians and Surgeons, Columbia University; and the Department of Health Care Policy, Harvard Medical School, Boston.. Address reprint requests to Dr. Olfson, New York State Psychiatric Institute/Department of Psychiatry, College of Physicians and Surgeons, Columbia University, 722 West 168th St., New York, NY 10032. Supported by NIMH grants MH-56490 (Dr. Olfson), MH-46376, MH-49098, and MH-52861; by the National Institute on Drug Abuse (through a supplement to grant MH-46376); and by the W.T. Grant Foundation (grant 90135190) (Dr. Kessler).

|

|

|

|

Figure 1. Kaplan-Meier Speed-of-Contact Curves for the Probability of First Treatment Contact for Major Depression or Dysthymia, Generalized Anxiety Disorder, Panic Disorder, Phobia, and Addictive Disorders in the United States and Ontarioa

1. Kessler RC, Olfson M, Berglund PA: Patterns and predictors of treatment contact after first onset of psychiatric disorders. Am J Psychiatry 1998; 155:62–69Link, Google Scholar

2. Wells KB, Burnam MA, Camp P: Severity of depression and fee-for-service general medical and mental health specialty practices. Med Care 1995; 33:350–364Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

3. Dew MA, Dunn LO, Bromet E, Schulberg HC: Factors affecting help-seeking during depression in a community sample. J Affect Disord 1988; 14:223–234Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

4. Olfson M, Pincus HA: Outpatient mental health care in nonhospital settings: distribution of patients across provider groups. Am J Psychiatry 1996; 153:1353–1356Link, Google Scholar

5. Padgett DK, Patrick C, Burns BJ, Schlesinger HJ: Ethnicity and use of outpatient mental health services in a national insured population. Am J Public Health 1994; 84:222–226Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

6. Temkin-Greener H, Clark KT: Ethnicity, gender, and utilization of mental health services in a Medicaid population. Soc Sci Med 1988; 26:989–996Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

7. Leaf PJ, Bruce ML, Tischler GL, Freeman DH Jr, Weissman MM, Myers JK: Factors affecting the utilization of specialty and general medical mental health services. Med Care 1988; 26:9–26Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

8. Gallo JJ, Marino S, Ford D, Anthony JC: Filters on the pathway to mental health care, II: sociodemographic factors. Psychol Med 1995; 25:1149–1160Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

9. Leaf PJ, Bruce ML, Tischler GL: The differential effect of attitudes on use of mental health services. Soc Psychiatry 1986; 21:187–192Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

10. Wells KB, Golding JM, Hough RL, Burnham A, Karno M: Factors affecting the probability of use of general and medical health and social/community services for Mexican Americans and non-Hispanic Whites. Med Care 1988; 26:441–452Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

11. Hu TW, Snowden LR, Jerrell JM, Nguyen TD: Ethnic populations in public mental health: services choice and level of use. Am J Public Health 1991; 81:1429–1434Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

12. Phillips MA, Murrell SA: Impact of psychological and physical health, stressful events, and social support on subsequent mental health help seeking among older adults. J Consult Clin Psychol 1994; 62:270–275Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

13. Sherbourne CD: The role of social support and life stress events in use of mental health services. Soc Sci Med 1988; 27:1373–1377Crossref, Google Scholar

14. Goodman SH, Sewells DS, Jampol RC: On going to the counselor: contributions of life stress and social supports to the decision to seek psychological counseling. J Couns Psychol 1984; 31:306–313Crossref, Google Scholar

15. Breakey WR, Kaminsky MJ: An assessment of Jarvis’ law in an urban catchment area. Hosp Community Psychiatry 1982; 33:661–663Abstract, Google Scholar

16. Joseph AE, Boeckh JL: Locational variation in mental health care utilization dependent upon diagnosis: a Canadian example. Soc Sci Med 1981; 15:395–440Google Scholar

17. Frank RG, McGuire TG: A review of studies of the impact of insurance on the demand and utilization of specialty mental health services. Health Serv Res 1986; 21:241–265Medline, Google Scholar

18. Keeler EB, Wells KB, Manning WG: The Demand for Episodes of Mental Health Services (R-3432-HHS.NIMH). Santa Monica, Calif, Rand Corp, 1986Google Scholar

19. Taube CA, Rupp A: The effect of Medicaid on access to ambulatory mental health care for the poor and near-poor under 65. Med Care 1986; 24:677–686Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

20. Yokopenic PA, Clark CA, Aneshensel CS: Depression, problem recognition, and professional consultation. J Nerv Ment Dis 1983; 171:15–23Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

21. Iglehart JK: The United States looks at Canadian health care. N Engl J Med 1989; 321:1767–1772Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

22. Detsky AS: Northern exposure: can the United States learn from Canada? N Engl J Med 1993; 38:805–807Google Scholar

23. Torrey EF, Bigelow DA, Sladen-Dew N: Quality and cost of services for seriously mentally ill individuals in British Columbia and the United States. Hosp Community Psychiatry 1993; 44:943–950Abstract, Google Scholar

24. Lippman DH, Lowy FH, Rickhi B: Attitudes of Ontario psychiatrists towards health insurance. Can Med Assoc J 1981; 125:167–170Medline, Google Scholar

25. Newell AR, Saltzman GM: Impact of reimbursement systems on child psychiatrists: a comparison of Canada and the United States. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 1995; 34:1326–1335Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

26. Sullivan RB, Watanabe M, Whitcomb ME, Kindig DA: The evolution of divergences in physician supply policy in Canada and the United States. JAMA 1996; 276:704–709Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

27. Freeman SJ: An overview of Canada’s mental health system, in Mental Health Care in Canada. Edited by Bachrach LL, Goering P, Wasylenki D. San Francisco, Jossey-Bass, 1994, pp 11–20Google Scholar

28. Blendon RJ, Donelan K, Leitman R, Epstien A, Cantor JC, Cohen AV, Morrison I, Moloney T, Koeck C, Levitt SW: Physicians’ perspectives on caring for patients in the United States, Canada, and West Germany. N Engl J Med 1993; 328:1011–1016Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

29. Kessler RC, McGonagle KA, Zhao S, Nelson CB, Hughes M, Eshleman S, Wittchen H-U, Kendler KS: Lifetime and 12-month prevalence of DSM-III-R psychiatric disorders in the United States: results from the National Comorbidity Survey. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1994; 51:8–19Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

30. Offord DR, Boyle M, Campbell D, Goring P, Lin E, Wrong M, Racine A: One year prevalence of psychiatric disorder in Ontarians 15 to 64 years of age. Can J Psychiatry 1996; 41:549–558Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

31. World Health Organization: Composite International Diagnostic Interview (CIDI), version 1.0. Geneva, WHO, 1990Google Scholar

32. Wittchen H-U: Reliability and validity studies of the WHO-Composite International Diagnostic Interview (CIDI): a critical review. J Psychiatr Res 1994; 28:57–84Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

33. Wittchen H-U, Kessler RC, Zhao S, Abelson J: Reliability and clinical validity of UM-CID DSM-III-R generalized anxiety disorder. J Psychiatr Res 1995; 29:95–110Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

34. Blazer DG, Kessler RC, McGonagle KA, Swartz MS: The prevalence and distribution of major depression in a national community sample: the National Comorbidity Survey. Am J Psychiatry 1994; 151:979–986 Link, Google Scholar

35. Wittchen HU, Zhao S, Abelson JM, Abelson JL, Kessler RC: Reliability and procedural validity of UM-CID DSM-III-R phobic disorders. Psychol Med 1996; 26:1169–1177Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

36. Kessler RC, Crum RM, Warner LA, Nelson CB, Schulenberg J, Anthony JC: Lifetime co-occurrence of DSM-III-R alcohol abuse and dependence with other psychiatric disorders in the National Comorbidity Survey. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1997; 54:313–321Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

37. Kaplan EL, Meier P: Nonparametric estimation from incomplete observations. J Am Stat Assoc 1958; 53:281–284Crossref, Google Scholar

38. Efron B: Logistic regression, survival analysis, and the Kaplan-Meier Curve. J Am Stat Assoc 1988; 83:415–425Crossref, Google Scholar

39. Kish L, Frankel MR: Inference from complex samples (with discussion). J R Stat Assoc, Series B, 1974; 36:1–37Google Scholar

40. Featherman DL: Schooling and occupational careers: constancy and change in worldly success, in Constancy and Change in Human Development. Edited by Brim OG Jr, Kagan J. Cambridge, Mass, Harvard University Press, 1980Google Scholar

41. Jencks C, Bartlett S, Corcoran M, Crouse J, Eaglesfield D, Jackson G, McClelland K, Mueser P: Who Gets Ahead? The Determinants of Economic Success in America. New York, Basic Books, 1979Google Scholar

42. Kessler RC, Frank RG, Edlund M, Katz SJ, Lin E, Leaf P: Differences in the use of psychiatric outpatient services between the United States and Ontario. N Engl J Med 1997; 336:551–557Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

43. Rochefort DA: More lessons, of a different kind: Canadian mental health policy in comparative perspective. Hosp Community Psychiatry 1992; 43:1083–1090Abstract, Google Scholar

44. Mechanic D, Schlesinger M, McAlpine DD: Management of mental health and substance abuse services: state of the art and early results. Milbank Q 1995; 73:19–55Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

45. Barer ML, Evans RG: Interpreting Canada: models, mind-sets, and myths. Health Aff (Millwood) 1992; 11:44–61Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

46. Brady J, Sharfstein SS, Muszynsky IL Jr: Trends in private insurance coverage for mental illness. Am J Psychiatry 1986; 143:1276–1279Link, Google Scholar

47. Taube CA, Mechanic D, Hohmann A (eds): The Future of Mental Health Services Research: DHHS Publication ADM 89-1600. Washington, DC, National Institute of Mental Health, 1989Google Scholar

48. Mechanic D: Medical Sociology, 2nd ed. New York, Free Press, 1978Google Scholar