Double-Blind, Fixed-Dose, Placebo-Controlled Study of Paroxetine in the Treatment of Panic Disorder

Abstract

OBJECTIVE: This study was designed to determine the minimum paroxetine dose effective for treating panic disorder. METHOD: Of 425 patients with DSM-III-R panic disorder with or without agoraphobia who underwent a 2-week drug-free screening period, 278 patients were randomly assigned to double-blind treatment with a 10-week course of placebo or paroxetine at a dose of 10, 20, or 40 mg/day. RESULTS: At 40 mg/day, paroxetine was superior to placebo across the majority of outcome measures. Despite a mean of 9.5 to 11.6 full panic attacks during the screening period, 86.0% of the patients taking 40 mg of paroxetine, 65.2% of those taking 20 mg, 67.4% of those taking 10 mg, and 50.0% of the placebo-treated patients were free of full panic attacks during the 2 weeks ending at week 10. The 40-mg paroxetine group experienced significantly greater global improvement than the placebo group and significantly greater improvement in frequency of full and limited-symptom panic attacks, intensity of full panic attacks, phobic fear, anxiety, and depressive symptoms, usually evident by week 4. All doses of paroxetine were well tolerated, and adverse effects were consistent with those associated with selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors. CONCLUSIONS: Paroxetine is an effective and well-tolerated short-term treatment of panic disorder. The minimum dose demonstrated to be significantly superior to placebo was 40 mg/day, although some patients did respond at lower doses. (Am J Psychiatry 1998; 155:36–42)

Interest in the role of potential serotonergic abnormalities in panic disorder has prompted clinical evaluation of the selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs). The SSRIs are generally well tolerated and have become popular treatments of panic disorder (1–3). Paroxetine (4, 5) and fluvoxamine (6–8) have been shown to be effective in controlled trials of panic disorder, and fluoxetine (9, 10) and sertraline (11) have been effective in open trials.

Oehrberg et al. (5) reported that paroxetine was significantly more effective than placebo in panic disorder (N=120). In that flexible-dose trial, ultimately 75% of the patients received 40 or 60 mg/day of paroxetine, but the minimal efficacious dose was not determined. In this report we summarize a multicenter trial designed to determine the minimal effective dose of paroxetine.

METHOD

Study Design

A double-blind, randomized, fixed-dose, placebo-controlled, parallel-design study was conducted in 20 centers in the United States and Canada. All patients received single-blind administration of placebo for 2 weeks. Patients meeting the entry criteria were then randomly assigned to receive placebo or 10, 20, or 40 mg/day of paroxetine for 10 weeks. The patients assigned to paroxetine began with 10 mg/day; the dose for the 20-mg and 40-mg groups was increased to 20 mg/day on day 8. The dose for the 40-mg group was increased to 40 mg/day on day 15. The patients were seen weekly during the first 4 weeks and biweekly thereafter.

The number of subjects calculated to ensure 90% power to detect a 30% difference in response rates with a 30% attrition rate was 79 patients at each dose level. The comparisons of primary interest were the three doses of active drug versus placebo. Dunnett's procedure was used to maintain an overall alpha level of 0.05 for the three comparisons of primary interest. The rejection region for the pairwise comparison was p<0.019.

Patient Selection

Men and women 18 years of age or older who met the DSM-III-R criteria for panic disorder with or without agoraphobia were enrolled. In addition, eligible patients must have had at least two full panic attacks in the 2-week screening period. The protocol was approved by the institutional review boards of all study centers, and the patients signed statements of informed consent.

A patient was excluded if he or she 1) was currently receiving psychotherapy; 2) had a current episode of primary major depression (i.e., preceding panic disorder and dominating the clinical presentation); 3) had another axis I disorder; 4) had a severe medical condition; 5) had substantial suicide risk; 6) had abused alcohol or other drugs recently; 7) was taking other psychotropic medication or oral anticoagulants concurrently; 8) had benzodiazepine withdrawal symptoms during screening; 9) had shown intolerance to an SSRI in the past; 10) had major laboratory abnormalities; 11) had pregnancy, lactation, or childbearing potential without medically acceptable contraception; or 12) had taken medication that would affect the study results.

Measurements

Four primary outcome measures were assessed for the 2-week period ending at week 10: 1) percentage of subjects free of panic attacks; 2) mean change from baseline in number of full panic attacks; 3) percentage of subjects with a 50% reduction from baseline in number of full panic attacks; and 4) Clinical Global Impression (CGI) score for severity of illness. The secondary outcome measures were mean number and intensity of full and limited-symptom panic attacks, number of unexpected and situational panic attacks, severity of anticipatory anxiety (percentage of time and intensity of worry about impending panic attacks), CGI global improvement score, and scores on the Marks-Sheehan Phobia Scale (12), Hamilton Anxiety Rating Scale (13), Montgomery-Åsberg Depression Rating Scale (14), Sheehan Disability Scale (15), and Social Adjustment Self-Report Questionnaire (16).

Full therapeutic response was defined as the absence of full panic attacks during the 2-week period ending at week 10. Patients who were still experiencing full panic attacks but for whom the number of attacks was reduced at least 50% were considered partial responders.

The patients were asked nonleading questions about adverse effects at each visit. Routine laboratory testing (i.e., clinical chemistry, hematology, and urinalysis) and physical examinations were conducted at baseline and week 10. Serum and urine samples were obtained at baseline and weeks 4 and 10 for detection of surreptitious benzodiazepine use.

Data Analysis

The SAS statistical analysis package (17) was used for all analyses. The percentage of patients achieving a dichotomous response (e.g., no full panic attacks) was analyzed by using logistic analysis of the categorical modeling procedure of the SAS system. The method produced chi-square tests for dose, site, and dose-by-site interaction and pairwise comparisons of each paroxetine dose versus placebo. Continuous data were analyzed by using parametric analysis of variance. Mean change from baseline in panic attack frequency was ranked and analyzed with the nonparametric Mann-Whitney U test. The statistical differences were two-tailed and considered to be significant at the 5% level. In the comparisons of paroxetine dose groups against placebo, Dunnett's multiple comparison procedure was used to maintain an overall alpha level of 0.05. This results in a critical region for pairwise tests of 0.019. Results for the intent-to-treat population were determined on the basis of the data sets for both completer analysis (observed cases) and end-point analysis (last observation carried forward).

RESULTS

Demographic Characteristics

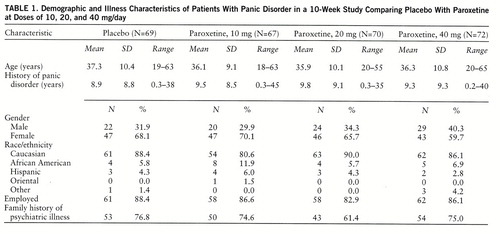

Of the 425 patients screened for eligibility, 147 patients did not fulfill the entry criteria. The intent-to-treat population (N=278) was randomly assigned to placebo (N=69) or to paroxetine at a dose of 10 mg/day (N=67), 20 mg/day (N=70), or 40 mg/day (N=72), resulting in comparable treatment groups (table 1).

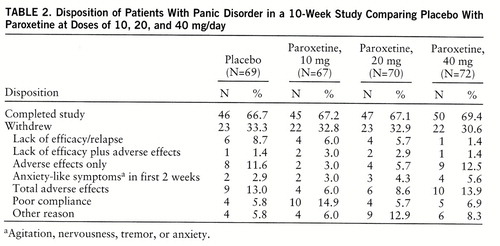

Of the 278 patients, 188 (67.6%) completed 10 weeks of treatment (table 2). Adverse effects were the most common reason for discontinuation for both the paroxetine groups and the placebo group. Withdrawals due to lack of efficacy decreased with increasing doses of paroxetine and were greatest for placebo. The seven patients with serum benzodiazepine concentrations of 3.5 ng/ml or above were evenly distributed across treatment groups and therefore were included.

Clinical Response

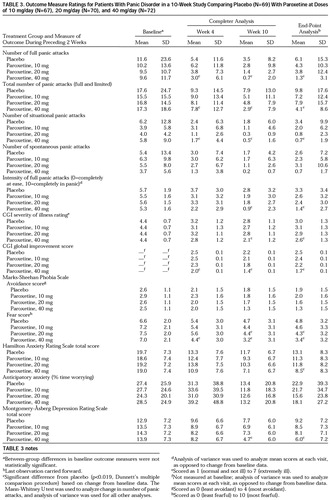

The treatment groups were not significantly different at baseline in panic disorder severity or secondary outcome measures (table 3). The patients treated with 40 mg/day of paroxetine achieved significantly greater improvements than the placebo group in three of the four primary outcome measures—panic-free status, reduction in full panic attacks, and improvement in CGI severity—but not in 50% reduction in panic attacks. There was also a strong numerical tendency (nonsignificant) favoring the 20-mg and 10-mg paroxetine groups over the placebo group.

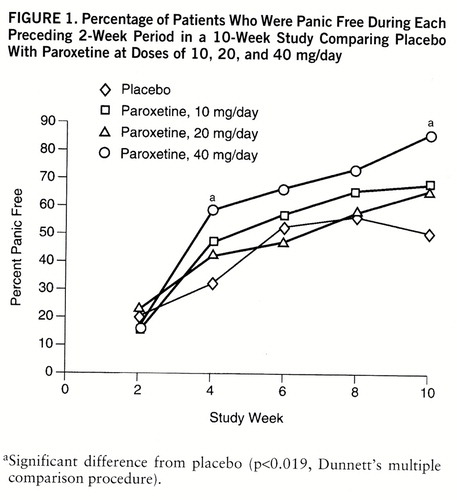

The difference in panic-free status between 40 mg/day of paroxetine and placebo attained statistical significance at 4 and 10 weeks (figure 1). During the final 2 weeks of the 10-week study, complete response was seen in 86.0% of the patients taking 40 mg/day of paroxetine, 65.2% of those taking 20 mg, 67.4% of those taking 10 mg, and 50.0% of the placebo-treated patients. There were no significant differences between the groups in the percentage of patients with partial responses (i.e., 50% reduction in number of full panic attacks).

The mean number of situational panic attacks for the 40-mg paroxetine group was significantly lower than the number for the placebo group at weeks 4 and 10, and the mean intensity of full panic attacks was significantly lower at week 10 (table 3). Differences in spontaneous panic attacks between treatment groups were not significant.

The mean CGI global and severity ratings were significantly lower at week 10 in the 40-mg group than in the placebo group. A rating of 1 (very much improved) or 2 (much improved) on the CGI global improvement scale was given at week 10 to 81.2% of the patients receiving 40 mg/day of paroxetine, 75.4% of those receiving 20 mg, 57.8% of those receiving 10 mg, and 51.5% of the placebo patients. The percent of patients responding to this extent was significantly higher in both the 40-mg and 20-mg paroxetine groups than in the placebo group at week 10 (p<0.019, logistic analysis, df=1).

The mean score for phobic avoidance on the Marks-Sheehan Phobia Scale declined nonsignificantly in all groups (table 3). The score for phobic fear was significantly lower for paroxetine than for placebo at weeks 4 (40 mg) and 10 (20 mg and 40 mg). Very few patients had no avoidance at baseline. However, among the 59 patients taking 40 mg/day of paroxetine for whom efficacy could be evaluated, six (85.7%) of the seven with no avoidance at baseline were full responders, compared to 37 (71.2%) of the 52 with baseline avoidance.

Significant improvement in the score on the Hamilton Anxiety Rating Scale (total) was observed for the 40-mg paroxetine group (in the end-point but not completer analysis). Anticipatory anxiety actually increased in all groups from baseline to week 4 but then declined, and there was no significant difference between any of the treatment groups and placebo (table 3).

Improvement in depressive symptoms (Montgomery-Åsberg Depression Rating Scale total score) was significantly greater for the 40-mg paroxetine group than for the placebo group at week 10 (table 3).

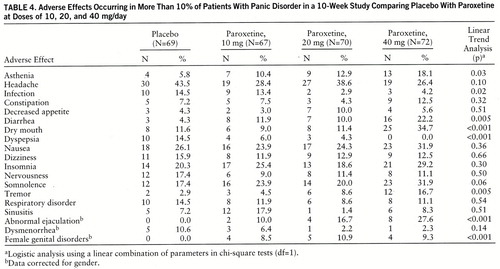

Tolerability

Overall, paroxetine was well tolerated, and the adverse effects were consistent with the usual SSRI side effects. The most frequently reported adverse effects are listed in table 4. Adverse effects resulting in premature study withdrawal occurred in 29 patients: nine (13.0%) from the placebo group, four (6.0%) from the 10-mg paroxetine group, six (8.6%) from the 20-mg group, and 10 (13.9%) from the 40-mg group. Nausea was the most common reason cited, occurring in eight patients (one taking placebo, one taking 10 mg of paroxetine, two taking 20 mg of paroxetine, and four taking 40 mg of paroxetine). Eleven patients, spread across all four groups, discontinued treatment within the first 2 weeks because of anxiety-like symptoms (table 2).

DISCUSSION

This study demonstrates that paroxetine at a dose of 40 mg/day is superior to placebo by week 4 across most outcome measures and is an effective and well-tolerated treatment of panic disorder with or without agoraphobia. Paroxetine at a dose of 10 or 20 mg/day showed a tendency toward superiority over placebo, but these differences did not attain statistical significance, possibly owing to the large placebo response and the relatively small number of patients in each group. Patients in the 40-mg group had a mean of 9.6 panic attacks during the 2-week baseline period, but 86.0% were completely free of panic attacks at week 10. There were also significant differences between the 40-mg and placebo groups at week 10 in intensity of full panic attacks, CGI severity rating, and global improvement.

Patients with panic disorder often suffer from multiple anxiety and depressive symptoms (18). We observed significant improvements in measures of phobic fear, anxiety, and depression with 40 mg/day of paroxetine.

Although the improvements in phobic avoidance were not statistically significant, 40 mg/day of paroxetine did result in significantly greater reductions in phobic fear. Because most effective antipanic agents do reduce agoraphobic avoidance, it is possible that paroxetine trials with greater power to detect differences would demonstrate significant improvement in phobic avoidance. Also, phobic avoidance usually improves later than do other symptoms, and perhaps a longer course of therapy would have resulted in greater reductions in avoidance. Also, higher doses may be required to reduce phobic avoidance, as has been observed with imipramine (19) and alprazolam (20). Further analysis of the clinical database of 218 paroxetine-treated panic patients indicates that more men than women met the treatment response criteria (72% versus 55%) (21), and the incidence of agoraphobia is lower among men (22). Clearly, the relationship between response in agoraphobic patients and treatment duration, dose, and gender requires further investigation.

We observed a substantial rate of response to placebo, which has become a problem in panic disorder studies, reaching as high as 50% (23) and 61% (24). The response to placebo in our study could be secondary to the frequent clinic visits, use of panic attack diaries, unintended cognitive restructuring, and escalating number of tablets provided during the first 3 weeks.

Paroxetine was well tolerated, and the adverse effects observed were those seen with the SSRIs: nausea, insomnia, somnolence, and sexual dysfunction (25). Adverse effects that were more common as the paroxetine dose increased were dry mouth, tremor, diarrhea, abnormal ejaculation, and female genital disorders. Studies comparing the side effects of paroxetine and other available treatments for panic disorder would be important, but paroxetine appears to be safe and well tolerated.

This study was not designed to measure the early treatment-related jitteriness or anxiety-like symptoms that have been reported with other SSRIs and tricyclic antidepressants (9, 10, 26–29). However, in the initial 2 weeks of treatment relatively little evidence of these activation-like symptoms was noted, and no patient withdrew from the study because of treatment-emergent jitteriness. Also, in the flexible-dose trial of paroxetine (5), exacerbation of jitteriness was not observed.

The relatively few comparative studies of antipanic agents make meta-analyses of effect sizes across studies a rational means for comparing treatments. In such a meta-analysis, Boyer (30) determined that SSRIs may be even more effective than tricyclic antidepressants or benzodiazepines for panic disorder.

The highest paroxetine dose used in this study, 40 mg/day, was the minimum dose demonstrated to be more effective than placebo, although some patients did respond to lower doses. Routine clinical practice should involve initial dosing at 10 mg/day, with gradual increases until a clinical response is observed. In this study, dose increases to 20 mg/day by week 2 and 40 mg/day by week 3 were well tolerated, and significant effects were observed among most outcome measures within 1 week after 40 mg/day was reached. Other studies with paroxetine (5) have suggested that even higher doses (60 mg/day) may be useful.

Cognitive behavior therapy is also an effective treatment of panic disorder, and the findings from current studies of combined pharmacotherapy and cognitive behavior therapy are promising (31).

Like treatment for major depression (32), panic disorder treatment for some patients needs to be extended (33) and may prevent or retard the return of panic symptoms. Indeed, preliminary analysis of a 12-week extension beyond this 10-week study (34) demonstrated maintenance of the antipanic effect of paroxetine (N=116). The patients with sustained response during this 12-week maintenance period were then randomly assigned to placebo (N=37) or the same dose of paroxetine (N=43) for an additional 12 weeks. The patients receiving paroxetine were significantly less likely to experience a relapse (5%) than were those who were switched to placebo (30%) (χ2=9.19, df=1, p=0.002).

Collectively, these data support the use of paroxetine for the short-term treatment of panic disorder and its long-term management.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The Paroxetine Panic Disorder Study Group consists of J. Ballenger and B. Lydiard (Charleston, S.C.); J. Carmen (Atlanta); G. Chouinard (Montreal); E. Coccaro (Philadelphia); L. Davis (Indianapolis); E. DuBoff (Denver); A. Feiger (Wheat Ridge, Colo.); J. Ferguson (Salt Lake City); S. Goldstein (New York); C. Houck (Birmingham, Ala.); J. Kreisle and M. Crismon (Austin, Tex.); J. Mattes (Princeton, N.J.); P. Morris (Toronto); D. Munjack (Beverly Hills, Calif.); C. Nemeroff and P. Ninan (Atlanta); P. Silverstone (Edmonton, Alta., Canada); S. Strawn and T. Rea (Bryan, Tex.); M. Tancer (Chapel Hill, N.C.); P. Tucker (Oklahoma City); and M. Van Ameringen (Hamilton, Ont., Canada).

|

|

|

|

Received Aug. 8, 1996; revisions received May 27 and July 14, 1997; accepted Aug. 8, 1997. From the Paroxetine Panic Disorder Study Group and from Clinical Research and Development, Medical Affairs, and Clinical Biometrics and Research Statistics, SmithKline Beecham Pharmaceuticals, Collegeville, Pa. Address reprint requests to Dr. Ballenger, Institute of Psychiatry, Medical University of South Carolina, 5th Floor, 171 Ashley Ave., Charleston, SC 29425; [email protected] (e-mail).

FIGURE 1. Percentage of Patients Who Were Panic Free During Each Preceding 2-Week Period in a 10-Week Study Comparing Placebo With Paroxetine at Doses of 10, 20, and 40 mg/day

aSignificant difference from placebo (p<0.019, Dunnett's multiple comparison procedure).

1. Ballenger JC: Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors: their use in the treatment of panic disorder, in Selective Serotonin Reuptake Inhibitors: Advances in Basic Research and Clinical Practice, 2nd ed. Edited by Feighner JP, Boyer WF. New York, John Wiley & Sons, 1996, pp 155–178Google Scholar

2. Sheehan DV, Harnett-Sheehan K: The role of SSRIs in panic disorder. J Clin Psychiatry 1996; 57(suppl 10):51–58Google Scholar

3. Davidson J, Lydiard RB, McCann U, Pollack M, Rosenbaum JF: Algorithm for the treatment of panic disorder with agoraphobia. Psychopharmacol Bull 1995; 31:457–507Medline, Google Scholar

4. Dunbar GC: A double-blind placebo controlled study of paroxetine and clomipramine in the treatment of panic disorder, in 1995 Annual Meeting New Research Program and Abstracts. Washington, DC, American Psychiatric Association, 1995, p 157Google Scholar

5. Oehrberg S, Christiansen PE, Behnke K, Borup AL, Severin B, Soegaard J, Calberg H, Judge R, Ohrstrom JK, Manniche PM: Paroxetine in the treatment of panic disorder: a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled study. Br J Psychiatry 1995; 167:374–379Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

6. Black DW, Wesner R, Bowers W, Gabel J: A comparison of fluvoxamine, cognitive therapy, and placebo in the treatment of panic disorder. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1993; 50:44–50Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

7. Den Boer JA, Westenberg HG: Effect of a serotonin and noradrenaline uptake inhibitor in panic disorder: a double-blind comparative study with fluvoxamine and maprotiline. Int Clin Psychopharmacol 1988; 3:59–74Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

8. Hoehn-Saric R, McLeod DR, Hipsley PA: Effect of fluvoxamine on panic disorder. J Clin Psychopharmacol 1993; 13:321–326Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

9. Gorman JM, Liebowitz MR, Fyer AJ, Goetz D, Campeas RB, Fyer MR, Davies SO, Klein DF: An open trial of fluoxetine in the treatment of panic attacks. J Clin Psychopharmacol 1987; 7:329–332Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

10. Schneier FR, Liebowitz MR, Davies SO, Fairbank J, Hollander E, Campeas R, Klein DF: Fluoxetine in panic disorder. J Clin Psychopharmacol 1990; 10:119–121Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

11. Gorman JM, Wolkow R: Sertraline as a treatment for panic disorder (abstract). Neuropsychopharmacology 1994; 10(35, part 2):1975Google Scholar

12. Marks IM, Matthews HM: Brief standard self-rating for phobic patients. Behav Res Ther 1979; 17:263–267Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

13. Hamilton M: The assessment of anxiety states by rating. Br J Med Psychol 1959; 32:50–55Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

14. Montgomery SA, Âsberg M: A new depression scale designed to be sensitive to change. Br J Psychiatry 1979; 134:382–389Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

15. Leon AC, Shear MK, Portera L, Klerman GL: Assessing impairment in patients with panic disorder: the Sheehan Disability Scale. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol 1992 27:78–82Google Scholar

16. Weissman MM: The Social Adjustment Self-Report Questionnaire, in Innovations in Clinical Practice: A Source Book, vol 5. Edited by Keller PA, Ritt LG. Sarasota, Fla, Professional Resource Exchange, 1986, pp 299–307Google Scholar

17. SAS User's Guide: Statistics, version 5.18. Cary, NC, SAS Institute, 1988Google Scholar

18. Keller MB, Hanks DL: Course and outcome in panic disorder. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry 1993; 17:551–570Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

19. Mavissakalian MR, Perel JM: Imipramine treatment of panic disorder with agoraphobia: dose ranging and plasma level-response relationships. Am J Psychiatry 1995; 152:673–682Link, Google Scholar

20. Lesser IM, Lydiard RB, Antel E, Rubin RT, Ballenger JC, DuPont R: Alprazolam plasma concentrations and treatment response in panic disorder and agoraphobia. Am J Psychiatry 1992; 149:1556–1562Link, Google Scholar

21. Steiner M, Oakes R, Wheadon D, Gergel IP: Predictors of response to paroxetine therapy in the treatment of panic disorder, in 1996 Annual Meeting New Research Program and Abstracts. Washington, DC, American Psychiatric Association, 1996, pp 122–123Google Scholar

22. Mavissakalian M: Male and female agoraphobia: are they different? Behav Res Ther 1985; 23:469–471Google Scholar

23. Ballenger JC, Burrows G, DuPont RL Jr, Lesser JM, Noyes R Jr, Pecknold JC, Rifkin A, Swinson RP: Alprazolam in panic disorder and agoraphobia: results from a multicenter trial, I: efficacy in short-term treatment. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1988; 45:413–422Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

24. Schweizer E, Patterson W, Rickels K, Rosenthal M: Double-blind, placebo-controlled study of a once-a-day, sustained-release preparation of alprazolam for the treatment of panic disorder. Am J Psychiatry 1993; 150:1210–1215Link, Google Scholar

25. Tollefson GD: Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors, in Textbook of Psychopharmacology. Edited by Schatzberg AF, Nemeroff CB. Washington, DC, American Psychiatric Press, 1995, pp 161–182Google Scholar

26. Amsterdam JD, Hornig-Rohan M, Maislin G: Efficacy of alprazolam in reducing fluoxetine-induced jitteriness in patients with major depression. J Clin Psychiatry 1994; 55:394–400Medline, Google Scholar

27. Ballenger JC, Lydiard RB, Turner SM: Panic disorder and agoraphobia, in Treatments of Psychiatric Disorders, 2nd ed, vol 2. Edited by Gabbard GO. Washington, DC, American Psychiatric Press, 1995, pp 1421–1452Google Scholar

28. Mavissakalian MR, Perel JM: Imipramine dose-response relationship in panic disorder with agoraphobia: preliminary findings. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1989; 46:127–131Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

29. Noyes R Jr, Garvey MJ, Cook BL, Samuelson L: Problems with tricyclic antidepressant use in patients with panic disorder or agoraphobia: results of a naturalistic follow-up study. J Clin Psychiatry 1989; 50:163–169Medline, Google Scholar

30. Boyer W: Serotonin uptake inhibitors are superior to imipramine and alprazolam in alleviating panic attacks: a meta-analysis. Int Clin Psychopharmacol 1995; 10:45–49Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

31. Mavissakalian M: Differential efficacy between tricyclic antidepressants and behavior therapy of panic disorder, in Clinical Aspects of Panic Disorder: Frontiers of Clinical Neuroscience, vol 9. Edited by Ballenger JC. New York, Wiley-Liss, 1990, pp 195–209Google Scholar

32. Frank E, Kupfer DJ, Perel JM: Three-year outcomes for maintenance therapies in recurrent depression. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1990; 47:1093–1099Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

33. Schatzberg AF, Ballenger JC: Decisions for the clinician in the treatment of panic disorder: when to treat, which treatment to use, and how long to treat. J Clin Psychiatry 1991; 52(Feb suppl):26–31Google Scholar

34. Burnham DB, Steiner M, Gergel IP, Oakes R, Bailer DC, Wheadon DE: Paroxetine long-term safety and efficacy in panic disorder and prevention of relapse: a double-blind study, in American College of Neuropsychopharmacology 34th Annual Meeting Abstracts of Panels and Posters. Nashville, Tenn, American College of Neuropsychopharmacology, 1995, p 201Google Scholar