Premenstrual Syndrome: Evidence for Symptom Stability Across Cycles

Abstract

OBJECTIVE: This study assessed cycle to cycle symptom stability in women with premenstrual syndrome (PMS). METHOD: Symptom ratings obtained prospectively over three or more symptomatic cycles from 16 women with PMS were analyzed. Measures of symptom severity and change were used to generate a coefficient of variation and an intraclass correlation coefficient (ICC) for each one of 14 symptoms across all cycles. In addition, symptoms were divided into three clusters, and the stability of the rank order of severity of symptoms within clusters and the correlation between symptom clusters were also calculated. RESULTS: In the 65 cycles studied, mood symptoms were the most prevalent. Mood symptoms—anxiety, irritability, and mood lability—had the lowest coefficients of variation but also the lowest ICCs of all symptoms. Within their respective symptom clusters, both physical and mood symptoms showed remarkable stability across cycles of their rank order of severity, but only the mood symptom cluster was highly correlated with functional impairment. CONCLUSIONS: Three mood symptoms—anxiety, irritability, and mood lability—were the most stable symptoms in this group of women with PMS. Mood and not somatic symptoms accounted for most of the functional impairment in this group of women. It is concluded that PMS is a stable syndrome that may best be viewed as part of the spectrum of recurrent mood disorders. (Am J Psychiatry 1997; 154:1741–1746)

While a myriad of symptoms—mood, behavioral, and physical—have been described as constituting premenstrual syndrome (PMS), none of these has been shown to be either necessary or sufficient for diagnostic purposes (1). The multitude of symptoms commonly observed in PMS is still fueling the debate over the classification of this syndrome among psychiatric conditions. In fact, the argument that premenstrual mood symptoms are an epiphenomenon of menstrual cycle-related somatic symptoms has yet to be convincingly refuted.

Studies examining the hierarchy of presenting symptoms across individuals with PMS have emphasized the interindividual variability. For example, Gotts et al. (2) asked women with PMS to rank order their four worst (most severe) PMS symptoms and found that while irritability and depression were reported as two of the four worst symptoms in 70% of the women, the identical order (ranking) of the four worst symptoms (out of 32) appeared only twice in 98 subjects. This variability has led to the use of factor and cluster analytic methods to attempt to define clinically meaningful subsyndromes (3). Often, these efforts employ ratings over a single cycle; yet, in the absence of the demonstration of stable patterns of symptom appearance across cycles, symptom clusters (as independent variables) cannot be regarded as meaningful. In addition, the measures employed to observe the course and treatment response characteristics of women with PMS presuppose the intercycle stability of the pattern of symptoms; i.e., one cannot assess the response to intervention if the symptom examined appears during the luteal phase in an inconsistent fashion. Only one study, to our knowledge, prospectively examined symptom stability across cycles, and it observed poor intercycle reliability (4).

In this study, therefore, we asked the following three questions:

1. Are individual symptoms experienced as part of PMS consistent across cycles and, therefore, appropriately employable as outcome measures in determining the course and treatment response characteristics of this syndrome?

2. Is the relative severity of symptoms within an individual maintained across cycles?

3. What is the relationship between ratings of mood or somatic symptoms and ratings of impairment?

To answer these questions we have employed a number of statistical methods to examine the stability of symptom self-ratings across several cycles in women with prospectively confirmed PMS.

METHOD

Subjects

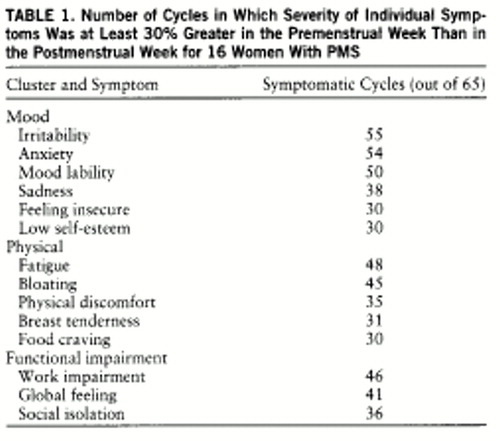

All subjects participating in this study provided written informed consent for collection of mood ratings. Symptom ratings were obtained from a data base collected over the past 5 years from women with diagnosed PMS. It consisted of daily, bipolar, 100-mm visual-analogue self-rating scores (in which a lower score indicates more symptoms) for 14 common PMS symptoms. The group of symptoms selected contains those most commonly reported but does not comprise all symptoms described in the diagnosis of PMS. The data were screened to identify those women with complete daily symptom records for three or more menstrual cycles (not necessarily consecutive) with at least two symptoms (one of which was a mood symptom) that met severity criteria for symptomatic PMS (30% increase in symptom severity, relative to the range of the scale used, from the follicular phase to the luteal phase). Thus, in order to be identified as meeting our severity criteria for the purpose of this study, the symptom not only had to be endorsed but also had to show a luteal phase-specific increase. Cycles were included only if the subject was medication free. Altogether, of data for 78 women reviewed, a complete medication-free data set was found for 16, consisting of 65 symptomatic cycles. Each of these 16 women met DSM-IV criteria for premenstrual dysphoric disorder, the diagnostic term by which we henceforth refer to our group. The total number of cycles in which a specific symptom was found to meet our severity criteria (as defined earlier) is summarized in table 1.

Statistical Analysis

1. Summary measures. For each of the 16 women, the mean symptom severity for each of 14 symptoms was calculated for the 7 days before menses (premenstrual score) and the 7 days after the cessation of menses for each symptomatic cycle. An additional measure was then calculated for further analysis: the percent change from the postmenstrual mean to the premenstrual mean (percent change). The premenstrual score indicates absolute severity of the symptom, while percent change expresses the degree of severity increase relative to baseline (the mean of the postmenstrual week scores). We employed one additional measure for analysis, the absolute difference between postmenstrual and premenstrual scores (delta); however, because findings from this measure were identical to those derived from percent change, the data from this measure will not be presented.

2. Coefficient of variation. The coefficient of variation, defined as the standard deviation divided by the mean, was used as a measure of the reproducibility of symptoms across symptomatic cycles; i.e., the lower the coefficient of variation (closer to zero), the more consistent the severity ratings are over different cycles. Coefficients of variation were calculated for the premenstrual score and percent change scores for each subject, for each one of the 14 symptoms, by calculating the mean across all of the cycles and dividing it into the standard deviation of the mean. Finally, a mean coefficient of variation for each of the symptoms was calculated by averaging the respective coefficient of variation for all subjects.

3. Intraclass correlation coefficient. To assess the consistency of symptom severity within a subject relative to variance between different subjects, an intraclass correlation coefficient (ICC) was calculated for each of the 14 symptoms. An ICC is different from a coefficient of variation in that it is a measure of variance across time within an individual relative to the variance between subjects, while the coefficient of variation is relative only to the individual. The ICC was calculated from an F value that was derived by dividing the mean square error terms for the between-patient variance by that of the within-patient variance. The higher the ICC (closer to 1), the more likely that individuals displayed consistent severity ratings across cycles (low within-subject variance), relative to marked differences in ratings seen across subjects (high between-subject variance).

4. Stability of ranks. In order to determine whether women rank their symptoms according to severity level in a consistent way over different cycles, the association (correlation) among the symptom severity scores was calculated. To perform this analysis we used Kendall's coefficient of concordance (5). This statistic is similar to the Spearman rank correlation coefficient but additionally allows one to determine the rank ordering of symptoms across multiple (more than two) time points. Thus, we used the Kendall statistic to measure the stability (over multiple cycles) of the symptom rank order in three clusters of symptoms: mood (six symptoms), physical (five symptoms), and functional impairment (three symptoms) (table 1). If the symptom rank order is perfectly consistent across the cycles, coefficient of concordance equals 1; i.e., if certain symptoms are consistently rated as more severe than other symptoms, the rank order is stable and will yield a significant Kendall statistic (coefficient of concordance).

5. Correlation between symptom clusters. In order to determine the relationship between physical symptoms, mood symptoms, and the degree of functional impairment, correlations were calculated between the three symptom clusters. This was accomplished first by calculating the cluster means from the premenstrual score for each symptom (i.e., the mean of the component symptom means for the mood, physical, and impairment clusters) for each patient and then by calculating the Pearson product-moment correlation coefficient between pairs of the three cluster means.

RESULTS

= In the 65 symptomatic cycles studied, the most common symptoms experienced (meeting our severity criteria) were irritability, anxiety, and mood lability—all mood symptoms. Almost as common was fatigue, a symptom that was classified as physical but that is commonly associated with mood disorders (table 1).

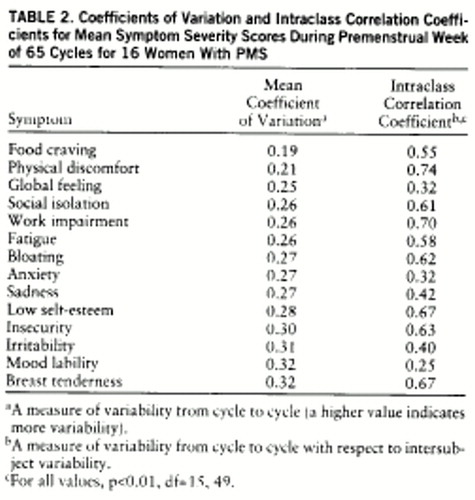

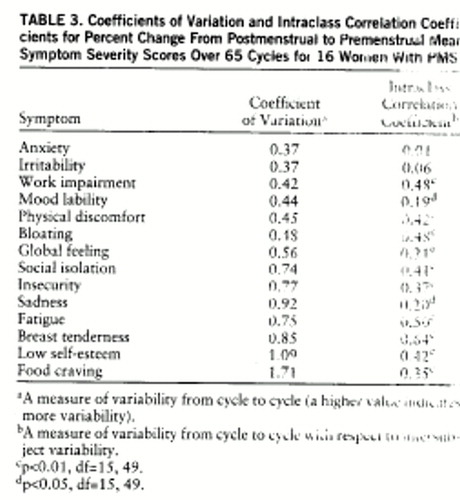

The coefficients of variation, as calculated from premenstrual scores, were all in the narrow range of 0.19–0.32 (table 2). In contrast, the lowest premenstrual score ICCs were found for mood symptoms—mood lability, anxiety, sadness, and irritability—as well as for global feeling, a measure of general impairment. When the coefficient of variation and ICC were calculated from the percent change scores (table 3), three of the five lowest coefficient of variation scores were mood symptoms (anxiety, irritability, and mood lability), and four of the five lowest ICCs were mood symptoms (anxiety, irritability, mood lability, and sadness). These data suggest that on the basis of premenstrual scores, all symptoms have stable severity scores (i.e., low coefficients of variation) across symptomatic cycles, but mood symptoms have a low consistency (a high variability) relative to the variance between subjects in the group (i.e., low ICC). On the basis of percent change scores, premenstrual increases in symptoms are most consistently seen across cycles for mood symptoms, which nonetheless show variability relative to differences seen across subjects.

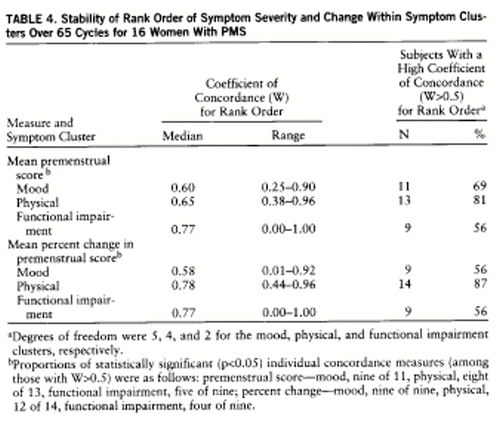

Results of the analysis of symptom rank order stability are presented in table 4. For the majority of the women, all three symptom clusters—mood, physical, and impairment—had a high concordance for rank order stability; i.e., the symptoms with the highest severity ratings in one cycle consistently were rated as the most severe symptoms experienced across other cycles, while the symptoms rated as less severe were also consistently rated so.

The Pearson product-moment correlation coefficients were 0.52 between mood symptoms and physical symptoms (df=14, p<0.05), 0.63 between physical symptoms and functional impairment (df=14, p<0.01), and 0.92 between mood symptoms and functional impairment (df=14, p<0.01).

DISCUSSION

Freeman et al. (6) observed that the five most frequent symptoms reported in a large sample of women presenting with histories of PMS were depression (56%), irritability (48%), anxiety (36%), mood swings (26%), and headaches (23%). Similarly, Hurt et al. (7) found that the symptoms with the highest prevalence among women presenting with PMS were anxiety, mood lability, anhedonia, depressed mood, decreased concentration, and sleep disturbance. The observation that the most frequent symptoms in our prospectively diagnosed group were irritability (85%), anxiety (83%), and mood lability (77%) confirms these earlier studies, suggesting that the study group is a representative one for women with PMS.

The coefficients of variation calculated for the different symptoms from premenstrual scores are remarkable both in their narrow range and their small magnitude. These small coefficient of variation scores can be interpreted to mean that all the symptoms were relatively stable and consistent across cycles during the symptomatic premenstrual week. The range of coefficient of variation scores (table 2) is too narrow to permit further comparison of the stability of the different symptoms.

Coefficients of variation calculated from percent change provide a better indication of the reproducibility of the change in symptom severity from the nonsymptomatic follicular phase to the symptomatic luteal phase. Three mood symptoms (anxiety, irritability, and mood lability), one impairment symptom (work impairment), and one physical symptom (physical discomfort) have the lowest coefficients of variation, indicating relatively good reproducibility. While such somatic symptoms as food craving, fatigue, and breast tenderness are commonly reported symptoms of PMS, our data suggest that they display lower reproducibility than mood symptoms.

One limitation in interpreting the calculated mean coefficients of variation is that the mean used to calculate the coefficient of variation is influenced by the type of scale employed, as well as by the frequency of symptom appearance across individuals. For example, if a symptom is less common, such as food cravings and physical discomfort, then it frequently will be rated (by asymptomatic women) as high on the visual-analogue self-rating scale (100 equals absence of symptoms), resulting in a high mean across cycles, and providing a small coefficient of variation for the same standard deviation. Thus, a small coefficient of variation in this case also reflects the frequency of the symptom presentation and not only its variability across cycles. Conversely, coefficients of variation calculated from percent change scores of less common symptoms may be spuriously increased, because symptoms that meet severity criteria in fewer cycles (e.g., food cravings) will generate smaller mean percent change scores (no change in symptom severity). A high coefficient of variation in these symptoms, therefore, may partly reflect small means in asymptomatic individuals and not only high variability across cycles.

The ICC in this study demonstrates whether the variance in symptom severity between the subjects is high relative to the variance within subjects across cycles. A high ICC score (close to 1) means small within-subject variance and large between-subject variance (the symptom is stable throughout different cycles for each subject, and there is large variability in its severity between subjects), while an ICC close to zero means either high within-subject variance or low between-subject variance (symptom is unstable across cycles or of similar severity between subjects). The ICCs calculated from premenstrual scores are notable for the low scores observed for all four major mood symptoms—anxiety, irritability, mood lability, and sadness. Since the coefficients of variation for these symptoms are small (suggesting relatively low variance across cycles), the explanation for the low ICCs is low between-subject variance. This would mean that mood symptoms show similar severity scores across cycles for most women who have premenstrual dysphoric disorder. Calculated from percent change, the ICC shows the same pattern, consistent with the stability of mood symptoms across cycles. In a similar fashion, the high ICCs and high coefficient of variation that we observed for breast tenderness (and to a lesser extent for insecurity and self-esteem) suggest the presence of high intersubject variability (high ICC), a consequence of the relatively inconsistent appearance across individuals, rather than a product of small within-subject variance.

Food craving, a symptom that is reported to be very common and severe in PMS (8), showed a different pattern compared with mood symptoms. It was less frequent in symptomatic women (seven of 16 women had no food cravings at all), had low premenstrual score coefficient of variation (0.19), had the highest percent change coefficient of variation (1.71), and had a midrange percent change ICC (0.35). The high percent change coefficient of variation implies low replicability, although, as discussed earlier, few cycles in our group were significant for food cravings, thus contributing to both the high percent change coefficient of variation (by providing a low mean percent change) and the low premenstrual score coefficient of variation (by providing a high, asymptomatic mean). Nonetheless, with such a high percent change coefficient of variation (high within-subject variability), the percent change ICC was not one of the lowest observed (0.35), indicating that the between-subject variability was also very high. In our group, then, this symptom was not only inconsistent across cycles in those women who did suffer from it, but was also highly variable in severity between women with premenstrual dysphoric disorder. It is worth noting that the studies reporting food craving to be prevalent and specific to PMS were based on retrospectively obtained symptom ratings (perhaps accounting for differences in our observations) but also found food craving to be independent of cyclic mood symptoms (9).

Women who rank order their presenting premenstrual symptoms seem to have an individualized symptom pattern (2). Our data suggest that the order in which women rank the severity of their symptoms is stable across several cycles in most women both for the mood and the physical symptoms. Clinically, this finding can be interpreted to mean that for each woman, the highest rated symptom in one cycle will predictably be the most severe in other cycles as well, even if the overall level of symptoms for those cycles is variable. The rank ordering of symptoms on the basis of severity is preserved across cycles.

Taken as a whole, our data suggest that episodes of premenstrual dysphoric disorder are characterized by considerable stability in symptom appearance from cycle to cycle. These observations give rise to several conclusions.

First, given the appearance of a stable pattern of symptoms across cycles, it is reasonable to attempt to identify and define symptom clusters (subsyndromes) that may be employed as independent variables and may be used to predict relevant differences in clinical history, biology, course, or treatment response characteristics. For example, Endicott et al. (3) have identified five PMS symptom clusters that were found to be differentially related to a lifetime diagnosis of mood disorder. Conversely, because of the low intersubject variance in mood symptoms, one could argue that nonmood and less prevalent symptoms might be better predictors of differential characteristics than specific mood symptoms.

Second, the stability of symptom appearance in symptomatic episodes of premenstrual dysphoric disorder can be interpreted to indirectly validate the concept of premenstrual dysphoric disorder as a syndrome as opposed to a variable epiphenomenon of menstrual cycle-related somatic symptoms. This notion is further strengthened by the high prevalence of mood symptoms during the symptomatic cycles and the strong correlation between functional impairment and mood symptoms that was observed in this study, as opposed to the weak correlation found with physical symptoms. A number of studies have looked at the stability of symptoms across episodes in other mood disorders. Leibenluft et al. (10) used a similar technique to evaluate symptoms of rapid cycling bipolar patients. Only six of 18 symptoms for depression and one of 11 symptoms for hypomania produced a coefficient of variation of less than 0.32, which was the highest coefficient of variation calculated in our study. Young et al. (11) found that the endogenous subtype of depression was unstable within patients across episodes, and Winokur et al. (12) found psychotic symptoms to be inconsistent in multiple episodes of mood disorder. Young et al. (13) reported that the concordance of depressive symptoms in bipolar and unipolar patients was low across two episodes unless corrected for episode intensity. In relation to these studies, the present data suggest remarkable stability of symptoms in premenstrual dysphoric disorder, further lending support to the notion that premenstrual dysphoric disorder is a mood syndrome and not an epiphenomenon of premenstrual molimina. In fact, because of the high stability of its mood symptoms, premenstrual dysphoric disorder may be useful in the study of mood disorders.

Third, the stability of symptoms across cycles observed in this study suggests that the use of these symptoms as outcome measures in determining the course of the syndrome, or the efficacy of therapeutic interventions, is appropriate. In contrast to our findings, Hart et al. (4) reported poor intercycle symptom reliability in women with PMS over two prospectively rated cycles. Two important methodological differences may account for the discrepancy between their study and ours. First, while in our study all women were prospectively diagnosed as having PMS according to stringent criteria (14), in the study by Hart et al., subjects were recruited as a sample of women who suffered “to some degree” from PMS. Second, Hart et al. followed their sample for two consecutive cycles, either one of which may not have been symptomatic. In the present study, all cycles that were used for the analyses met criteria for being symptomatic, thus minimizing variance due to asymptomatic cycles.

Finally, in our group, depression was the fourth most common mood symptom meeting our severity criteria. It is possible that sadness was actually more common in our group but at severity levels that did not meet our threshold criteria (30% increase from postmenopausal to premenstrual weeks). In this study, the symptoms of irritability, mood lability, and anxiety appear to be more consistent across cycles than sadness. Our findings also are supported by recent data from Bancroft et al. (1997 personal communication), who reported that of 347 women attending a PMS clinic (38% of whom had a past history of treatment for depression), 32% demonstrated premenstrual depression, 37% tension, and 43% irritability. Clearly, sadness is a symptom that is frequently endorsed and often meets syndromic criteria. Nonetheless, it is appropriate to allow for the possibility that premenstrual dysphoric disorder is related to the anxiety disorder spectrum.

One possible source of bias in this study may be the fact that symptomatic cycles were selected on the basis of having at least one mood symptom. Theoretically, this could have accounted for the higher number of mood symptoms present in our group and thus could have biased for less variability in mood measures. However, in our group some mood symptoms occurred infrequently (insecurity, low self-esteem), while other somatic symptoms such as fatigue and bloating were common. Furthermore, since every symptomatic cycle that was selected had on average 8.7 different symptoms that met severity criteria, it seems unlikely that the prerequisite of having one mood symptom significantly biased our results.

CONCLUSIONS

Symptoms in women with premenstrual dysphoric disorder that are of clinically significant severity are highly replicable from cycle to cycle within individuals. Three mood symptoms—anxiety, irritability, and mood lability—were the most common symptoms reported and were the most reproducible for each woman. Not only were the different symptoms found to be stable for each woman, the individual constellation of symptoms (i.e., rank order of severity) proved to be highly stable in the majority of the women. This finding extends observations that women with premenstrual dysphoric disorder have individual-specific symptom patterns by showing that this pattern is stable and replicable across cycles. Finally, our data further emphasize the primary role of mood symptoms in premenstrual dysphoric disorder and support the classification of premenstrual dysphoric disorder as part of the spectrum of recurrent mood disorders.

|

|

|

|

Received April 23, 1996; revisions received Jan. 16 and April 7, 1997; accepted May 12, 1997. From the Behavioral Endocrinology Branch, NIMH. Address reprint requests to Dr. Rubinow, NIMH, Bldg. 10, Rm. 3N238, 10 Center Dr., MSC 1276, Bethesda, MD 20892-1276.

1. Rubinow DR, Roy-Byrne P, Hoban MC, Gold PW, Post RM: Prospective assessment of menstrually related mood disorders. Am J Psychiatry 1984; 141:684–686Link, Google Scholar

2. Gotts G, Morse CA, Dennerstein L: Premenstrual complaints: an idiosyncratic syndrome. J Psychosom Obstet Gynaecol 1995; 16:29–35Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

3. Endicott J, Nee J, Cohen J, Halbreich U: Premenstrual changes: patterns and correlates of daily ratings. J Affect Disord 1986; 10:127–135Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

4. Hart WG, Coleman GJ, Russell JW: Assessment of premenstrual symptomatology: a re-evaluation of the predictive validity of self-report. J Psychosom Res 1987; 31:185–190Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

5. Kendall M, Gibbons JD: Rank Correlation Methods, 5th ed. New York, Oxford University Press, 1990Google Scholar

6. Freeman EW, Sondheimer S, Weinbaum PJ, Rickels K: Evaluating premenstrual symptoms in medical practice. Obstet Gynecol 1985; 65:500–505Medline, Google Scholar

7. Hurt SW, Schnurr PP, Severino SK, Freeman EW, Gise LH, Rivera-Tovar A, Steege JF: Late luteal phase dysphoric disorder in 670 women evaluated for premenstrual complaints. Am J Psychiatry 1992; 149:525–530Link, Google Scholar

8. Bancroft J: The premenstrual syndrome—a reappraisal of the concept and the evidence. Psychol Med Suppl Suppl 1993; 24:1–47Crossref, Google Scholar

9. Bancroft J, Williamson L, Warner P, Rennie D, Smith SK: Perimenstrual complaints in women complaining of PMS, menorrhagia, and dysmenorrhea: toward a dismantling of the premenstrual syndrome. Psychosom Med 1993; 55:133–145Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

10. Leibenluft E, Clark CH, Myers FS: The reproducibility of depressive and hypomanic symptoms across repeated episodes in patients with rapid-cycling bipolar disorder. J Affect Disord 1995; 33:83–88Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

11. Young MA, Keller MB, Lavori PW, Scheftner WA, Fawcett JA, Endicott J, Hirschfeld RMA: Lack of stability of the RDC endogenous subtype in consecutive episodes of major depression. J Affect Disord 1987; 12:139–143Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

12. Winokur G, Scharfetter C, Angst J: Stability of psychotic symptomatology (delusions, hallucinations), affective syndromes, and schizophrenic symptoms (thought disorder, incongruent affect) over episodes in remitting psychoses. Eur Arch Psychiatry Neurol Sci 1985; 234:303–307Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

13. Young MA, Fogg LF, Scheftner WA, Fawcett JA: Concordance of symptoms in recurrent depressive episodes. J Affect Disord 1990; 20:79–85Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

14. NIMH Premenstrual Syndrome Workshop Guidelines. Rockville, Md, National Institute of Mental Health, 1983Google Scholar