Help Seeking and Perceived Need for Mental Health Care Among Individuals in Canada With Suicidal Behaviors

Despite the disability and low quality of life associated with mental disorders ( 1 ), a significant proportion of individuals with mental disorders do not seek help ( 2 , 3 , 4 ). Studies examining a broad range of mental disorders confirm that untreated mental illness is a prevalent phenomenon across the world ( 5 , 6 , 7 , 8 ). Use of mental health services is especially important among individuals with suicidal ideation and suicide attempts, because unmet needs might increase the likelihood of completed suicide ( 9 , 10 , 11 ). In fact, two large audits suggest that some suicides may be preventable if services address the needs of individuals with suicidal behaviors ( 12 , 13 ). The prevalence of self-perceived need for mental health care among those with suicidal behaviors is unclear. This is especially important, given that studies suggest that those who do not perceive a need are unlikely to use services ( 14 ).

The available research, consisting of only five studies with significant limitations, suggests that individuals with suicidal behaviors are more likely than those without suicidal behaviors to use services ( 15 , 16 ) and perceive a need for treatment ( 15 , 17 , 18 ). A major limitation in this scant body of literature lies in the fact that mental disorders are rarely taken into account. Two studies that have addressed this limitation suggest that individuals with suicidal behaviors are more likely to receive care if they have a co-occurring mental disorder ( 15 , 19 ). However, conclusions of these studies are limited by the fact that diagnoses were either restricted (that is, one study examined depression only) or suboptimal (that is, one study relied on "probable" mental disorders). Because of these factors, it remains unclear whether suicidal behaviors themselves are associated with increases in help seeking and perceived need or whether increases are due to underlying mental disorders. Finally, previous studies have examined suicidal ideation exclusively or have combined suicidal ideation with suicide attempts, although the two behaviors may have differential relationships with help seeking and perceived need.

To our knowledge, all existing studies examining help seeking and perceived need in relation to suicidal behaviors have taken an atheoretical approach. In contrast, Andersen's behavioral model of health services use ( 20 ) is commonly used in the broader help-seeking literature as a guiding theoretical model. Andersen's model suggests that individuals' predisposing characteristics, enabling resources, and need (evaluated and perceived) determine health service use and, subsequently, health outcomes. This model can be used to further expand the understanding of suicidal behaviors and help seeking. For example, previous studies have not examined various aspects of Andersen's model—specifically, barriers to receiving care and satisfaction with care received among individuals with suicidal behaviors. Studies have suggested that a significant proportion of individuals with suicidal behaviors who do receive services report that their needs were not fully met (39%–60%) ( 15 , 17 ), further warranting the consideration of these factors.

The study presented here addressed the limitations discussed above; included older adolescents, an age group rarely considered in the literature; and used a nationally representative Canadian sample. The objectives of this study were to examine and compare factors related to help seeking among individuals with mental disorders and no suicidal behaviors, those with suicidal ideation with or without mental disorders, and those with a suicide attempt with or without mental disorders.

Using Andersen's model as a framework, this study examined the presence of psychiatric disorders and suicidal behaviors (evaluated need) in predicting contact with health professionals (health service use) and perceived need. Furthermore, this study examined barriers to care (enabling resources) and satisfaction with health professionals (health outcome) in relation to psychiatric disorders and suicidal behaviors (evaluated need).

Methods

Sample

Data came from the public use files of a survey designed by Statistics Canada called the Canadian Community Health Survey Cycle 1.2 (CCHS 1.2) (N=36,984) ( 21 ). This survey, conducted in 2002 by professional interviewers, examined a target population of persons aged 15 or older living in private dwellings in the ten Canadian provinces. Individuals living in the three territories, First Nations communities, or institutions were excluded. A multistage stratified cluster design was used to ensure that the sample would be representative of the Canadian general population, and a very good response rate of 77% was achieved. A detailed description of the method of selection for household interviews is reported elsewhere ( 22 ).

Measures

Sex, age (15–24, 25–44, 45–64, or 65 and older), education (less than high school versus high school or more), marital status (married or cohabiting; separated, divorced, or widowed; or never married), and household income (by quartile: low income, lower-middle income, upper-middle income, or high income) were included as covariates in all analyses because of published findings of associations ( 18 ) and significant associations between each of these sociodemographic variables and help seeking and perceived need in preliminary analyses.

The World Health Organization Composite International Diagnostic Interview (CIDI) ( 23 , 24 ) was used to assess psychiatric disorders. These included past-year diagnoses of major depression, mania, panic attacks, social phobia, agoraphobia, alcohol dependence, and drug dependence. Good concordance has been demonstrated between lay-person-administered CIDI diagnoses and clinician-administered Structured Clinical Interview diagnoses (SCID) ( 25 , 26 ). On the basis of these diagnoses, a four-category covariate was created reflecting number of mental disorders (zero, one, two, or three or more). Because comorbidity of mental disorders has been shown to be associated with both suicidality ( 27 , 28 ) and help seeking ( 18 , 29 ) and because of differences in the prevalence of mental disorders across the three groups examined, this variable was included as a covariate in analyses examining help seeking and perceived need to adjust for severity of mental disorders.

Because of the sensitive nature of questions regarding suicidal behaviors, respondents were given a list of experiences and the interviewer asked whether each experience had ever happened to the respondent. The experiences reflecting suicidal ideation and suicide attempt were, "You seriously thought about committing suicide or taking your own life" and "You attempted suicide or tried to take your own life." If respondents endorsed these experiences, they were asked whether this experience had occurred in the past year.

A three-category variable was created to reflect the presence of past-year mental disorders or suicidal behaviors among respondents, with categories indicating any past-year mental disorder without any past-year suicidal behaviors, past-year suicidal ideation with or without any past-year mental disorder, and past-year suicide attempt with or without any past-year mental disorder. Individuals who reported both past-year suicidal ideation and suicide attempt were categorized into the third group.

Respondents were asked various questions about their use of services in the past year for problems with their emotions, mental health, or use of alcohol or drugs. Specific questions assessed the type of health professional the individual had contact with in the past year as well as whether individuals were hospitalized or used emergency room services in the past year. An additional variable reflecting any help seeking was created on the basis of these sources of contact. Additionally, individuals who had contact with specific professionals were asked how satisfied they were with the treatments and services they received in the past year. Individuals who responded that they were very satisfied or satisfied were coded as "satisfied," whereas those who responded that they were neither satisfied nor dissatisfied, dissatisfied, or very dissatisfied were coded as "not satisfied."

The respondents were also asked whether they perceived a need for help with their emotions, mental health, or use of alcohol or drugs in the past year but did not receive such services. Respondents who endorsed a perceived but unmet need were then asked what type of help they felt they needed but did not receive. Five categories of perceived need were assessed (information about mental illness and its treatments or availability of services, therapy or counseling, help with financial or housing problems, skills training, or medication). Respondents who endorsed a perceived unmet need were also asked to endorse items from a list of 13 potential barriers. Respondents could endorse multiple barriers.

Analytic strategy

Past-year help seeking, perceived need, satisfaction with services, and barriers to receiving care were examined in the three groups (mental disorder without suicidal behavior, suicidal ideation with or without a mental disorder, and suicide attempt with or without a mental disorder) using cross-tabulations and multivariate logistic regressions. A trichotomous variable reflecting these three groups was entered as the independent variable in all regressions. In order to compare the three groups, regression models were used both with past-year mental disorder without suicidal behavior category as the reference group and with past-year suicidal ideation with or without a mental disorder category as the reference group. All regression models were adjusted for sociodemographic factors of sex, age, education, marital status, and household income. Number of mental disorders was also entered as a covariate in regression models examining help seeking and perceived need.

In all analyses, appropriate stratifications and statistical weights were applied to ensure that the data were representative of the general population ( 22 ). In order to account for the complex sampling design of the survey, Taylor series linearization, a variance estimation procedure, was also employed using SUDAAN software ( 30 ) in all analyses.

Results

Of the 36,984 persons aged 15 years and older surveyed, 4,872 had a mental disorder without suicidal behaviors, 1,234 had suicidal ideation, and 230 had attempted suicide in the past year.

Help seeking and perceived need

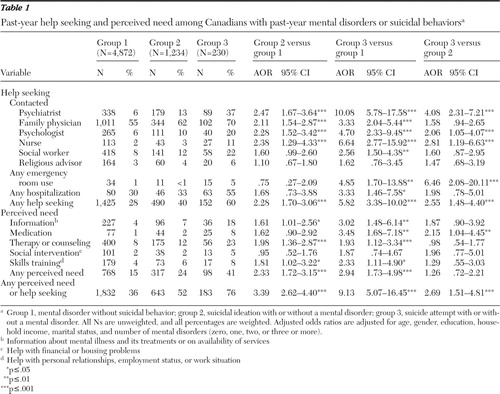

Table 1 shows past-year help seeking and perceived need in the three groups. Among individuals who reported past-year suicidal ideation, 40% had contact with any health professional in the past year. The majority of individuals with a past-year suicide attempt reported having contact with a health professional, although 40% of these individuals did not have any such contact. The most common source of help reported by all three groups was the family physician. Individuals who reported suicidal ideation had significantly higher odds of endorsing most help-seeking variables, compared with those who had a mental disorder but no suicidal behaviors. Individuals who reported a suicide attempt also had significantly higher odds of endorsing nearly all of the help-seeking variables, compared with individuals with a mental disorder but no suicidal behaviors. Individuals who reported a suicide attempt were significantly more likely than those who reported suicidal ideation to have seen a psychiatrist, psychologist, or nurse; to have had an emergency room visit; and to have had any help seeking.

|

In terms of perceived need, 41% of individuals with a suicide attempt felt that they needed help that they did not receive in the past year, whereas 24% of those with suicidal ideation felt this way. The most common type of help all three groups felt they required and did not receive was therapy or counseling. Individuals with suicidal ideation were significantly more likely than those with a mental disorder without suicidal behaviors to endorse a perceived need for information, therapy or counseling, and skills training and to endorse any perceived need. Individuals who reported a suicide attempt were significantly more likely than those with a mental disorder without suicidal behaviors to endorse all perceived needs except a need for social intervention, and they were more likely than individuals with suicidal ideation to endorse a perceived need for medication. Finally, approximately 48% of those with suicidal ideation and 24% of those with a suicide attempt reported they did not seek help and did not perceive a need for help in the past year. Individuals with a suicide attempt were significantly more likely than those with suicidal ideation to report any perceived need or help seeking, and those with suicidal ideation were more likely than those with mental disorders without suicidal behaviors to endorse this variable.

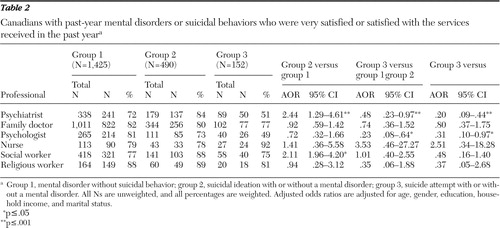

Satisfaction with health professionals

Table 2 shows satisfaction with services among individuals who received services in the past year. Rates of satisfaction ranged from 49% to 92% in the three groups, but few significant differences existed between groups. Individuals with suicidal ideation were significantly more likely than those with mental disorders without suicidal behaviors to be satisfied with their psychiatrist and social worker. Individuals with a suicide attempt were significantly less likely than the other two groups to be satisfied with their psychiatrist and psychologist.

|

Barriers to care

Table 3 shows barriers to care among individuals who had a perceived need for care in the past year. Individuals with suicidal ideation were significantly less likely than those with a mental disorder without suicidal behaviors to endorse a barrier of not knowing how or where to get help. Individuals with a suicide attempt were significantly more likely than those with a mental disorder and no suicidal behaviors to report that professional help was not available at the time required. Finally, individuals with a suicide attempt were significantly more likely than individuals with suicidal ideation to report barriers of not knowing how or where to get help and problems with transportation, children, or scheduling.

|

Discussion

In accordance with the existing literature ( 15 , 16 , 17 , 18 ), our results indicated that individuals with suicidal ideation and suicide attempts had significantly greater rates of help seeking and perceived need, compared with those with mental disorders without suicidal behaviors. Several differences in satisfaction and barriers to care were observed between individuals with mental disorders only, individuals with suicidal ideation with or without mental disorders, and individuals with a suicide attempt with or without mental disorders. The study presented here extends the literature by showing that differences in help seeking and perceived need persist despite adjustment for sociodemographic factors and number of mental disorders. This suggests that suicidal behaviors are associated with increased help seeking and perceived need over and above the presence and severity of mental disorders.

According to Andersen's model, a central determinant of help seeking is need (both perceived and evaluated). Mental disorders and suicidal behaviors are clearly sources of evaluated need as evidenced by classifications within psychiatric nosology as well as associations with distress, disability, and completed suicide ( 4 , 29 ). Results from the study reported here support Andersen's model in that an increased level of evaluated need was associated with an increased likelihood of help seeking. Specifically, individuals with suicidal ideation and those with a suicide attempt were significantly more likely than those with a mental disorder without suicidal behaviors to seek help, suggesting that suicidal behaviors are important evaluated need factors associated with help seeking over and above the presence of mental disorders. Furthermore, individuals who had attempted suicide were even more likely than those with suicidal ideation to seek help, suggesting increasing need with the severity of the suicidal behavior.

Despite the fact that individuals with a suicide attempt were more likely than those with a mental disorder and no suicidal behavior to seek help, 40% of these individuals did not seek any form of help examined, and only 55% were hospitalized. Furthermore, only 5% were evaluated in an emergency room. An even greater proportion of individuals with suicidal ideation (60%) did not seek any form of help, with only 33% in this group hospitalized and less than 1% evaluated in an emergency room. Given these findings, outreach approaches, such as gatekeeper training ( 31 ) and public awareness campaigns, represent an important avenue for identifying individuals with suicidal behaviors. Primary interventions at the community level in high-risk populations are also imperative. Although these individuals report important components of evaluated need, they are not seeking appropriate care.

One potential explanation for this lack of help seeking lies in perceived need. Although related, evaluated need and perceived need are different in many ways. Without a perceived need, evaluated need may not promote help seeking. In accordance with Andersen's model, individuals with suicidal ideation and those with a suicide attempt were significantly more likely than those with a mental disorder and no suicidal behavior to have a perceived need for treatment. However, 59% of individuals with a suicide attempt and 76% of individuals with suicidal ideation did not perceive any need for treatment. This clearly complicates health service delivery and leads to an important question of how these individuals can first be identified and then helped. Individuals with suicidal ideation or a suicide attempt who received health services sought out a family doctor most often, emphasizing the need for general practitioners to inquire about, recognize, and appropriately address suicidal behaviors. Because a lack of perceived need can be a crucial impeding factor to help seeking, general practitioners must attempt to carefully assess mental disorders and suicidal behaviors among their patients.

Although included within Andersen's model, enabling resources have been infrequently studied in the literature on suicidal behaviors and help seeking. These factors can either encourage or discourage an individual from seeking help. Perceived barriers to care are examples of factors that function to dissuade an individual from seeking help. The study presented here found that barriers to care are common among individuals with significant evaluated need. In order to provide services, such barriers need to be addressed. The most common barriers reported among individuals with suicide attempts were a lack of knowledge about where to get services and unavailability of professional help at the necessary time. The barrier most commonly reported by individuals with suicidal ideation was a preference to manage the problem themselves. Again, as primary care physicians are most likely to make first contact with these individuals, it is extremely important that they actively inquire about suicidal behaviors ( 32 ). Family physicians can play a fundamental role in informing these individuals about available resources and directing them to other health professionals if necessary. Because both individuals with suicidal ideation and those with suicide attempts most commonly perceived a need for therapy or counseling, it is especially important that primary care physicians screen for these needs and refer patients to a trained mental health professional who can provide this service.

The findings of the study presented here should be considered in light of several limitations. The CCHS 1.2 is a cross-sectional survey, which prevents any inferences of temporality or causality. Furthermore, timing of service delivery was not assessed, and as a result, it is impossible to know whether suicidal behaviors occurred before or after services were received. Second, the assessment of suicidal behaviors, although possessing face validity, was brief, and lethality of suicide attempts was not assessed. Third, results of this study may not be generalizable to individuals with the most severe suicidal behaviors and mental disorders, because institutionalized individuals were excluded from the CCHS 1.2. Fourth, some barriers to care that are important for individuals with suicidal behaviors may not have been assessed. Indeed, 7% of individuals with a suicide attempt and 12% of individuals with suicidal ideation endorsed "other" barriers. Fifth, significant differences found between the three groups with regard to satisfaction with care and perceived barriers to care are preliminary and require replication. Finally, trained lay interviewers conducted all assessments. Clinicians may have been better able to assess suicidal behaviors or provide a context within which suicidal behaviors may have been more willingly discussed.

Conclusions

Although suicidal behaviors represent a significant source of evaluated need associated with help seeking and perceived need over and above the presence and severity of mental disorders, a significant proportion of individuals with a suicide attempt and those with suicidal ideation do not seek help nor perceive a need for treatment. There is a need for outreach and educational programs such as gatekeeper training ( 31 ) so that individuals with suicidal behavior can receive timely mental health care.

Acknowledgments and disclosures

This research was supported by a Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council Canada Graduate Scholarship, by a Canadian Institutes of Health Research (CIHR) New Investigator Award (grant 152348), and by the Swampy Cree Suicide Prevention Team CIHR Operating Grant 82894. The opinions in this article do not represent the opinions of Statistics Canada.

The authors report no competing interests.

1. Alonso J, Angermeyer MC, Bernert S, et al: Disability and quality of life impact of mental disorders in Europe: results from the European Study of the Epidemiology of Mental Disorders (ESEMeD) project. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica 109:38–46, 2004Google Scholar

2. Kessler RC, Demler O, Frank RG, et al: Prevalence and treatment of mental disorders, 1990 to 2003. New England Journal of Medicine 352:2515–2523, 2005Google Scholar

3. Sareen J, Cox BJ, Afifi TO, et al: Mental health service use in a nationally representative Canadian survey. Canadian Journal of Psychiatry 50:73–81, 2005Google Scholar

4. Kessler RC, Berglund P, Demler O, et al: The epidemiology of major depressive disorder: results from the National Comorbidity Survey Replication (NCS-R). JAMA 289:3095–3105, 2003Google Scholar

5. Bergeron E, Poirier L, Fournier L, et al: Determinants of service use among young Canadians with mental disorders. Canadian Journal of Psychiatry 50:629–636, 2005Google Scholar

6. Wang PS, Aguilar-Gaxiola S, Alonso J, et al: Use of mental health services for anxiety, mood and substance disorders in 17 countries in the WHO world mental health surveys. Lancet 370:841–850, 2007Google Scholar

7. Bijl RV, de Graaf R, Hiripi E, et al: The prevalence of treated and untreated mental disorders in five countries: the work of an international consortium finds sizable populations whose mental conditions are not being treated. Health Affairs 22(3):122–133, 2003Google Scholar

8. Andrews G, Henderson S, Hall W: Prevalence, comorbidity, disability and service utilisation: overview of the Australian National Mental Health Survey. British Journal of Psychiatry 178:145–153, 2001Google Scholar

9. Tejedor MC, Diaz A, Castillon JJ, et al: Attempted suicide: repetition and survival—findings of a follow-up study. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica 100:205–211, 1999Google Scholar

10. Suominen K, Isometsa E, Suokas J, et al: Completed suicide after a suicide attempt: a 37-year follow-up study. American Journal of Psychiatry 161:562–563, 2004Google Scholar

11. Portzky G, Audenaert K, van Heeringgen K: Psychosocial and psychiatric risk factors associated with adolescent suicide: a case-control psychological autopsy study. Journal of Adolescence, in pressGoogle Scholar

12. Burgess P, Pirkis J, Morton J, et al: Lessons from a comprehensive clinical audit of users of psychiatric services who committed suicide. Psychiatric Services 51:1555–1560, 2000Google Scholar

13. Appleby L, Shaw J, Amos T, et al: Suicide within 12 months of contact with mental health services: national clinical survey. British Medical Journal 318:1235–1239, 1999Google Scholar

14. Edlund MJ, Unützer J, Curran GM: Perceived need for alcohol, drug and mental health treatment. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology 41:480–487, 2006Google Scholar

15. Brook R, Klap R, Liao D, et al: Mental health care for adults with suicide ideation. General Hospital Psychiatry 28:271–277, 2006Google Scholar

16. Pirkis JE, Burgess PM, Meadows GN, et al: Suicidal ideation and suicide attempts as predictors of mental health service use. Medical Journal of Australia 175:542–545, 2001Google Scholar

17. Pirkis J, Burgess P, Meadows G, et al: Self-reported needs for care among persons who have suicidal ideation or who have attempted suicide. Psychiatric Services 52:381–383, 2001Google Scholar

18. Mojtabai R, Olfson M, Mechanic D: Perceived need and help-seeking in adults with mood, anxiety or substance use disorders. Archives of General Psychiatry 59:77–84, 2002Google Scholar

19. Rhodes AE, Bethell J, Bondy SJ: Suicidality, depression, and mental health service use in Canada. Canadian Journal of Psychiatry 51:35–41, 2006Google Scholar

20. Andersen RM: Revisiting the behavioral model and access to medical care: does it matter? Journal of Health and Social Behavior 36:1–10, 1995Google Scholar

21. Gravel R, Beland Y: The Canadian Community Health Survey: mental health and well-being. Canadian Journal of Psychiatry 50:573–579, 2005Google Scholar

22. Bailie L, Dufour J, Hamel M: Data Quality Assurance for the Canadian Community Health Survey. Ottawa, Ontario, Statistics Canada, 2002Google Scholar

23. Kessler RC, Wittchen H-U, Abelson JM, et al: Methodological studies of the Composite International Diagnostic Interview (CIDI) in the US National Comorbidity Survey (NCS). International Journal of Methods in Psychiatric Research 7:33–55, 1998Google Scholar

24. Wittchen H-U: Reliability and validity studies of the WHO Composite International Diagnostic Interview (CIDI): a critical review. Journal of Psychiatric Research 28:57–84, 1994Google Scholar

25. First MB, Spitzer RL, Gibbon M, et al: Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Axis I Disorders, Research Version, Non-patient Edition (SCID-I/NP). New York, New York State Psychiatric Institute, Biometrics Research, 2002Google Scholar

26. Haro JM, Arbabzadeh-Bouchez S, Brugha TS, et al: Concordance of the Composite International Diagnostic Interview Version 3.0 (CIDI 3.0) with standardized clinical assessments in the WHO World Mental Health Surveys. International Journal of Methods in Psychiatric Research 15:167–180, 2006Google Scholar

27. Kessler RC, Berglund P, Borges G, et al: Trends in suicide ideation, plans, gestures and attempts in the United States, 1990–1992 to 2001–2003. JAMA 293:2487–2495, 2005Google Scholar

28. Kessler RC, Borges G, Walters EE: Prevalence of and risk factors for lifetime suicide attempts in the National Comorbidity Survey. Archives of General Psychiatry 56:617–626, 1999Google Scholar

29. Sareen J, Cox BJ, Afifi TO, et al: Perceived need for mental health treatment in a nationally representative Canadian sample. Canadian Journal of Psychiatry 50:447–455, 2005Google Scholar

30. Shah BV, Barnswell BG, Bieler GS: SUDAAN User's Manual: Software for the Analysis of Correlated Data. Research Triangle Park, NC, Research Triangle Institute, 1995Google Scholar

31. Isaac M, Elias B, Katz L, et al: Gatekeeper training as a preventative intervention for suicide: a systematic review. Canadian Journal of Psychiatry, in pressGoogle Scholar

32. McNab C, Meadows G: The General-practice Users' Perceived-need Inventory ("GUPI"): a brief general practice tool to assist in bringing mental healthcare needs to professional attention. Primary Care Mental Health 3:93–101, 2005Google Scholar