A Qualitative Analysis of the Perception of Stigma Among Latinos Receiving Antidepressants

A number of strategic research goals have been highlighted to improve the care of mental illnesses, such as depression, among Latinos, a traditionally underserved group ( 1 ). Major depression treatment is often complicated by poor adherence to medication ( 2 ), and this problem has been reported to occur more frequently among Latino patients ( 3 ). As a result, strategic research goals have included the improvement of antidepressant adherence among Latino patients ( 1 ). This has included the exploration of variables related to medication adherence, such as perceived stigma ( 4 ). The importance of studying stigma among Latinos is further underscored by the fact that stigma varies according to culture ( 5 ). Stigma generally refers to the negative social evaluation associated with a particular label, such as mental illness. Stigma may be one of the most significant barriers to improving mental health ( 6 ), and it has been shown to negatively affect antidepressant adherence ( 4 ).

The study presented here examined the perception of stigma related to antidepressants among a group of Latino outpatients. The study utilized qualitative methods because of this approach's utility for generating new ethnically relevant information ( 7 ). The data are presented within a previously reported conceptual framework for stigma that is comprised of various components ( 8 ). The components include labeling, negative associations conferred upon those who are labeled, social separation, and consequences—that is, discrimination and increased barriers in society. This study also focused on whether individuals resist or accept the stigma.

Methods

Six focus groups were conducted with Latinos receiving treatment for depression. The groups were conducted as part of a larger study to develop an intervention to improve antidepressant adherence among Latinos. Participants were recruited from a community mental health center, where they were receiving outpatient psychotropic and psychotherapeutic treatment for depression. Most were referred by their clinicians, although some were self-referred via recruitment flyers. Inclusion criteria required that they were receiving antidepressants for depression, were not diagnosed as having psychosis, were Hispanic or Latino, and were between the ages of 18 and 65 years. No formal diagnostic information was collected. A total of 51 participants were recruited. One person declined to participate, and 20 were not enrolled because of difficulty with scheduling or contacting. A total of 30 participants participated in the focus groups, which were conducted between April 2006 and August 2006.

Each focus group was begun by completing the informed consent procedure, which was approved by the institutional review board of the University of Medicine and Dentistry, New Jersey-Robert Wood Johnson Medical School. Participants signed consent forms after a complete description of the study was provided. Participants also completed a demographic questionnaire. Once the groups commenced, the conversation followed a discussion guide. [An appendix showing the discussion guide is available as an online supplement at ps.psychiatryonline.org.] The discussion guide, which consisted of 11 topics related to issues of antidepressant adherence and culture, did not include questions directly related to stigma. Rather, issues of stigma emerged as participants discussed other aspects of antidepressant adherence. All groups were conducted in Spanish, lasted from 90 to 120 minutes, and were audio recorded for subsequent analysis.

Each audio recording was transcribed into text. The text files were imported into ATLAS.ti, a qualitative analysis software program. ATLAS.ti facilitates the storing, management, and visualization of qualitative data (that is, quotes, memos, and codes), particularly when the data are complex as a result of numerous codes and multiple raters. Grounded theory is a qualitative analysis approach that systematically describes data in a way that draws from the data, rather than from preconceived theories or concepts ( 9 ). As part of this analytic approach, two raters (AI and IM) independently read through each transcript multiple times and coded text that was related to stigma. The raters then reviewed each other's text coded as stigma and discussed discrepancies to arrive at a consensus. The analysis presented here focused on the issue of stigma, but the overall analysis included the coding of various issues related to antidepressant use.

Results

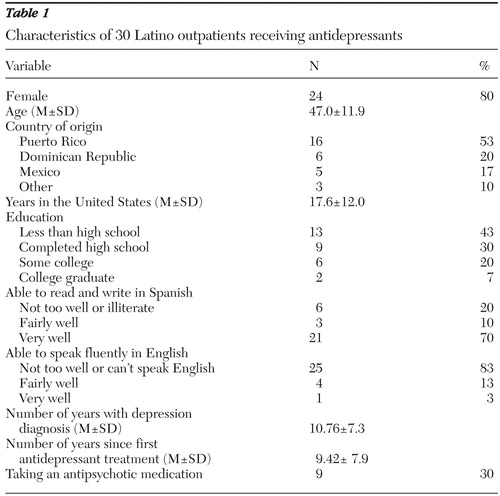

Table 1 displays the characteristics of the sample. Although there was some diversity across the demographic variables, the participants were mostly women from Puerto Rico, the Dominican Republic, and Mexico. Issues of stigma frequently occurred in participants' descriptions of their experiences with antidepressants. Of the adherence complications, stigma ranked second only to side effects, which was discussed by 26 (87%) of the participants. Twenty-two (73%) participants made comments that were coded as being related to stigma. There were 86 instances of stigma coded by the raters overall.

|

An expected finding was participants' perception that experiences with depressive symptoms are labeled negatively, particularly within their social contexts. This labeling extended to both their depression and use of antidepressant medication. One participant described the label for antidepressant use, "Yo si oía decir de la medicina de que eso era para locos." (I did hear people say about the medicine that it was for crazy people.)

Ample evidence emerged that illustrated the negative attributes that participants associated with antidepressant medication. Participants appeared to struggle with many of these negative attributes mostly when first confronting their diagnosis and with the commencement of antidepressant treatment. The examples we present are mostly participants' own expressed thoughts during this process and not necessarily comments from others.

One negative association of antidepressants was that they were for "severe" cases. One participant reported her initial reaction to the treatment recommendation, "¿Bueno, tan grande es mi problema?" (Well, so my problem is that big?) Weakness and inability to deal with life's problems were also reported to be among the negative associations linked to depression and antidepressant medications. This view was illustrated by some of the pejorative labels reported—for example, floja or weak, inútil or useless, and chiquitita or small. Reactions to the initial recommendation for antidepressant medications again illustrated the role that these negative associations played.

"Ay Dios mío, que inútil yo voy a ser… . Me sentí muy chiquitita. Por que si yo estoy bien, yo no necesito eso. Yo estoy bien. Yo podía hacer mis cosas sin medicamento. Yo podía. Yo era otra persona. ¿Por que me pasa esto? ¡Ay, mucho!" (Oh my God, how useless I will be… . I felt very small. Because if I'm fine, I wouldn't need this. I'm fine. I could do my things without medication. I could. I was another person. Why does this happen to me? Ahh, too much!)

Taking antidepressants was also seen as subjecting one to some of the negative associations typically related to taking drugs. This included the potential for addiction, which has long been a common misperception with antidepressants. It should be noted that drug addiction has an independent and very negative connotation in Latino culture. Negative perceptions also included the fear that others would associate taking antidepressant medications with being under narcotic effects.

"Muchas de las personas piensan por el hecho de estar tomando medicamentos antidepresivos es como las personas que toman cocaína y todas esas cosas, que van a estar así." (Many people think that because they are taking antidepressant medications, it's like people who are using cocaine and all those other things, that they're going to be like that.)

Participants depicted a social environment that carried negative connotation and disapproval related to depression and antidepressant medication. Whether by fear of negative evaluation or actual behaviors from others, one result from such a social context was the experience of separation for those who were targets of stigma. For example, separation was evident in the use of labels for antidepressants—for example, "para los locos" (for crazy people). Also, separation occurred when the cultural context was such that the use of antidepressant medication was not normative. Cultural expectations described by participants emphasized being resilient and coping with life's problems without antidepressants. Taking antidepressants seemed to subject participants to disapproval from their family and social support systems. One family member reportedly stated, "Yo tantos problemas que he tenido y nunca he tenido que ir a un psiquiatra. ¿En que fallaste tu? ¿Qué tu hiciste?" (I've had so many problems, and I have never had to go to a psychiatrist. What did you fail in? What did you do?)

In these instances, family members were described as exerting a direct influence on whether the medications should be taken. Such stigma would also contribute to family dysfunction in the form of conflicts, negative statements, and limited support. These consequences are noteworthy given that those with depression are already likely to be struggling with a negative sense of self and interpersonal dysfunction. It should be noted that such lack of support was not reported by all participants.

Other consequences were described in occupational and social domains. A notable example was related to discontinuation of antidepressant medication before seeking employment. The participant described concern about being negatively evaluated as a result of antidepressant treatment. Other examples described a fear of the social impact of being seen entering the mental health clinic.

Although discussing issues related to depression and antidepressants, participants revealed instances of both acceptance of and resistance to stigma. Some participants revealed clear examples of accepting or internalizing the stigma.

"Muchas veces uno piensa que si uno le habla a los demás, que ellos pensarán que uno es loco. Entonces a veces uno mismo piensa, '¿Será verdad?' Como que la depresión es un miedo tan fuerte que uno piensa que si es verdad, que uno esta loco." (Many times you think that if you talk to others, they will think that you are crazy. Then sometimes you think, "Is it true?" As if the depression is a fear so strong that you think that yes it's true, you're crazy.)

In contrast, other participants seemed to resist stigma by directly rejecting terms like loco. Participants also resisted the stigma by adapting their thinking or by educating individuals within their social networks regarding depression and its treatment.

"Yo les explico que lo que estoy tomando es para mi cerebro… . 'Ve los efectos secundarios, es algo que a mi me hace falta, porque no ando ni drogada ni borracha.' Le explico que es una falta de células, 'Es un suplemento que necesito para mi cerebro.' Así los convenzo." (I explain to them that what I am taking is for my brain… . "See the side-effects, it's something that I am missing, because I am neither drugged nor drunk." I explain to them that it's a lack of cells, "It's a supplement that I need for my brain." That's how I convince them.)

During the focus groups, participants were asked to describe important aspects of being Latino or Hispanic. Common features included being family oriented (familismo), helpful toward one another, and united. These features were reported by 22 (73%), 14 (47%), and nine (30%) participants, respectively. Together, these self-perceived characteristics reflected a collectivist orientation. Other frequently cited characteristics were related to being trabajadores (hardworking), luchadores (people who fight against problems), and aprovechadores (people who take advantage) of the opportunities available in the United States. The combination of these characteristics was reported by 19 participants (63%). Many of these self-perceived cultural characteristics were at odds with the perceived negative attributes of taking antidepressants. For example, the values of being a hardworking person who struggles to overcome problems contradicted the association of weakness ascribed to antidepressants. Furthermore, being family oriented is likely to contribute to ambivalence about accepting the diagnosis of depression or depression treatment when a family member espouses stigmatizing views. In these cases, patients must overcome an additional barrier to treatment.

"Si, pase mucho, sufrí mucho y segundo como que la familia no me entendía. Como que se creían que lo que yo tenía no era nada, changuerías. ¿Entiendes? Entonces, pues yo me sentía mal. Y le explicaba y ellos me decían, 'Tu lo que tienes que hacer es dejar todas esas medicinas y botarlas.'" (Yes, I went through a lot, I suffered a lot, and secondly, it was like my family did not understand me. It was as if they thought that what I had was nothing, a joke. Do you understand? Then, well I would feel bad. I would explain to them and they would say to me, "What you need to do is stop all those medications and throw them out.")

Discussion

The significance of stigma and antidepressant use is noteworthy given that none of the focus group questions directly inquired about stigma. Despite this lack of specific probing, stigma emerged as one of the most common adherence issues. This is consistent with the finding that Latinos have greater stigma concerns, compared with non-Hispanic whites ( 10 ). We found that the stigma of antidepressant use implied social deficiencies. These included weakness or inability to cope with stressors and the presence of severe problems or a severe mental disorder. In addition, using antidepressants was seen as being equivalent to using illicit drugs. Many of these issues parallel previous work ( 11 , 12 , 13 ). Our data also illustrated the consequences of stigma, which seemed to contribute to social and occupational fears. Consequences also included discontinuation of antidepressant use. Overall, our results suggest that the dimensions of stigma proposed by Link and Phelan ( 8 ) are useful for understanding stigma among Latinos with depression. We also found that the cultural context is interconnected with stigma, in which self-described values among Latinos in our focus groups were at odds with the perceived negative attributes of antidepressant use. These issues exemplify unique cultural contributions to stigma that may have particularly important implications for antidepressant adherence ( 3 ).

The study presented here was not designed to study stigma, and this is its major limitation. Future studies whose primary aims include stigma can utilize more focused questions related to the topic. At the same time, however, the strong emergence of stigma within general discussions of adherence illustrates the salience of this phenomenon. In addition, because participants were mostly monolingual Latinas from the Caribbean and Mexico who had extensive experience with antidepressant treatment, our findings are limited in generalizing to other Latinos with depression. It is noteworthy that stigma appeared to be very relevant among our participants, who have been involved with treatment for many years and have likely "accepted" treatment. Thus a potential line of inquiry would lead one to examine stigma among those who have not accepted treatment and can be presumed to harbor greater perceptions of stigma. Alternatively, the perceptions of stigma may have been greater in this group because of the adverse effects of a chronic experience with depression.

The methodology used in this study was also limited in differentiating between the perception of stigma versus the actual experience of stigma. However, these perceptions, which this study sought to describe, are important because they may influence behavior. Although all participants were referred for antidepressant treatment, diagnostic and depression severity data were not collected. This is an additional limitation, particularly given that depression severity may perhaps be related to treatment motivation and treatment acceptance.

In the study presented here, qualitative data were used as a preliminary approach to discover cultural information pertaining to antidepressant adherence. Future studies should employ hypothesis-driven, quantitative methodologies or mixed methods to confirm our findings ( 7 ). If confirmed, stigma measures should be adapted to include content domains that represent some of the issues described herein. This would allow researchers to measure the degree to which the issues reported here apply to various Latino samples. Furthermore, interventions for treatment adherence may benefit from giving consideration to the issues identified in this study.

Conclusions

Stigma is a significant concern among Latinos receiving antidepressants. Participants perceived stigma related not only to their depression but also to their use of antidepressant medication. As part of stigma, antidepressant use among Latinos has negative associations, which leave patients fearing social consequences. Finally, cultural values and stigma are interconnected.

Acknowledgments and disclosures

This study was funded by grant K23-MH-074860 from the National Institute of Mental Health.

Dr. Interian has an unrestricted educational grant from Forrest Laboratories, Inc. The other authors report no competing interests.

1. Vega WA, Karno M, Alegria M, et al: Research issues for improving treatment of US Hispanics with persistent mental disorders. Psychiatric Services 58:385–394, 2007Google Scholar

2. Katon W, von Korff M, Lin E, et al: Adequacy and duration of antidepressant treatment in primary care. Medical Care 30:67–76, 1992Google Scholar

3. Olfson M, Marcus SC, Tedeschi M, et al: Continuity of antidepressant treatment for adults with depression in the United States. American Journal of Psychiatry 163:101–108, 2006Google Scholar

4. Sirey JA, Bruce ML, Alexopoulos GS, et al: Perceived stigma as a predictor of treatment discontinuation in young and older outpatients with depression. American Journal of Psychiatry 158:479–481, 2001Google Scholar

5. Weiss MG, Jadhav S, Raguram R, et al: Psychiatric stigma across cultures: local validation in Bangalore and London. Anthropology and Medicine 8:71–87, 2001Google Scholar

6. Perlick DA: Special section on stigma as a barrier to recovery: introduction. Psychiatric Services 52:1613–1614, 2001Google Scholar

7. Bernal G, Scharron-del-Rio MR: Are empirically supported treatments valid for ethnic minorities? Toward an alternative approach for treatment research. Cultural Diversity and Ethnic Minority Psychology 7:328–342, 2001Google Scholar

8. Link BG, Phelan JC: Conceptualizing stigma. Annual Review of Sociology 27:363–385, 2001Google Scholar

9. Strauss A, Corbin J: Basics of Qualitative Research. Thousand Oaks, Calif, Sage 1998Google Scholar

10. Nadeem E, Lange JM, Edge D, et al: Does stigma keep poor young immigrant and US-born black and Latina women from seeking mental health care? Psychiatric Services 58:1547–1554, 2007Google Scholar

11. Ayalon L, Arean PA, Alvidrez J: Adherence to antidepressant medications in black and Latino elderly patients. American Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry 13:572–580, 2005Google Scholar

12. Martinez Pincay IE, Guarnaccia PJ: "It's like going through an earthquake": anthropological perspectives on depression among Latin immigrants. Journal of Immigrant Health 9:17–28, 2007Google Scholar

13. Pyne JM, Kuc EJ, Schroeder PJ, et al: Relationship between perceived stigma and depression severity. Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease 192:278–283, 2004Google Scholar