Psychopathology During Childhood and Adolescence Predicts Delusional-Like Experiences in Adults: A 21-Year Birth Cohort Study

Abstract

Objective: Community surveys have shown that many otherwise well individuals report delusional-like experiences. The authors examined psychopathology during childhood and adolescence as a predictor of delusional-like experiences in young adulthood. Method: The authors analyzed prospective data from the Mater-University of Queensland Study of Pregnancy, a birth cohort of 3,617 young adults born between 1981 and 1983. Psychopathology was measured at ages 5 and 14 using the Child Behavior Checklist (CBCL) and at age 14 using the Youth Self-Report (YSR). Delusional-like experiences were measured at age 21 using the Peters Delusional Inventory. The association between childhood and adolescent symptoms and later delusional-like experiences was examined using logistic regression. Results: High CBCL scores at ages 5 and 14 predicted high levels of delusional-like experiences at age 21 (odds ratios for the highest versus the other quartiles combined were 1.25 and 1.85, respectively). Those with YSR scores in the highest quartile at age 14 were nearly four times as likely to have high levels of delusional-like experiences at age 21 (odds ratio=3.71). Adolescent-onset psychopathology and continuous psychopathology through both childhood and adolescence strongly predicted delusional-like experiences at age 21. Hallucinations at age 14 were significantly associated with delusional-like experiences at age 21. The general pattern of associations persisted when adjusted for previous drug use or the presence of nonaffective psychoses at age 21. Conclusion: Psychopathology during childhood and adolescence predicts adult delusional-like experiences. Understanding the biological and psychosocial factors that influence this developmental trajectory may provide clues to the pathogenesis of psychotic-like experiences.

Behavioral dysfunction during childhood and adolescence can foreshadow the development of psychopathology in adulthood. For example, several population-based prospective studies have documented social, behavioral, and emotional antecedents in children who later develop schizophrenia and related disorders (1) . These studies have tended to focus on clinical diagnostic categories (e.g., schizophrenia, nonaffective psychoses) as outcome measures. However, in recent years there has been increasing interest in the idea that features of psychosis can be conceptualized along a continuum (2) . Subclinical psychotic-like experiences are much more prevalent than clinically defined psychotic disorders. A recent systematic review and meta-analysis reported that psychotic-like experiences are found, on average, in about 5% of the general population (3) .

The research community has been particularly interested in psychotic-like experiences as antecedents of clinical disorders. For example, there is evidence to suggest that psychotic-like experiences are associated with an increased risk of developing mood disorders (4 , 5) and substance use disorders (6) as well as psychotic disorders (7 , 8) . From this perspective, delusional-like experiences and hallucinations have been viewed as “intermediate phenotypes” that may be of importance either in predicting later psychosis or as a phenomenological feature that may share etiological or pathogenic mechanisms with full clinical syndromes.

A complementary type of research has examined delusional-like experiences and hallucinations as outcome variables. In a recently published systematic review, van Os and colleagues (3) reported that delusional-like experiences and hallucinations were associated with developmental stage, child and adult social adversity, psychoactive drug use, male sex, and migrant status. To our knowledge, no population-based study has examined broad childhood and adolescent psychopathology as an antecedent of adult psychotic-like experiences.

The main aim of this study was to explore the emotional and behavioral antecedents of delusional-like experiences, as measured by the Peters Delusional Inventory, based on a large Australian birth cohort study (9) . The cohort study included detailed assessments of psychopathology at 5 years and 14 years, and we had the opportunity to include a detailed evaluation of delusional-like experiences at 21 years in the most recent follow-up. Given the findings that the clinical syndrome of psychosis is associated with psychopathology during childhood and adolescence (8) and that psychotic-like experiences predict the clinical syndrome of psychosis (3) , we predicted that increased psychopathology during childhood and adolescence would be associated with delusional-like experiences in adulthood.

Method

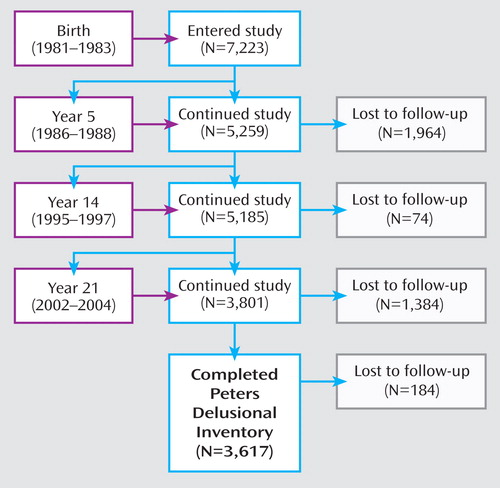

Participants

The Mater-University of Queensland Study of Pregnancy is a prospective longitudinal cohort study of mothers and their offspring who received antenatal care at a major public hospital in Queensland, Australia, between 1981 and 1983 (10) . Data were collected on 7,223 singleton live-birth offspring and their mothers. The mothers and offspring have undergone prospective follow-ups at 6 months, 5 years, 14 years, and, most recently, 21 years (9) . Figure 1 indicates the cohort sample size at the various follow-up points (excluding the 6-month follow-up).

Written informed consent was obtained from the mother at all data collection phases and from the young adult at the 21-year follow-up. Ethical approval for this study was obtained from the University of Queensland Ethics Committee.

Measures

We used the 21-item version of the Peters Delusional Inventory (PDI) to measure adult delusional-like experiences. This instrument, which was based on the Present State Examination (11) , has been used to measure delusional-like experiences in clinical and community populations (12 , 13) . The PDI explores a wide range of beliefs; examples of questions include the following: “Do you ever feel as if you are possessed by someone or something else?”; “Do you ever feel as if people seem to drop hints about you or say things with a double meaning?”; “Do you ever feel as if all things in magazines or on TV were written especially for you?”; “Do you ever feel as if someone is deliberately trying to harm you?”; “Do you ever think that people can communicate telepathically?”; “Have your thoughts ever been so vivid that you were worried other people would hear them?”; and “Do you ever feel as if other people can read your mind?” The PDI total score is designed to capture a distribution of scores rather than to provide a discrete clinical threshold.

Several instruments were used to measure broad psychopathology and substance use in childhood and adolescence. The Child Behavior Checklist (CBCL; 14 ) is a parent-report instrument developed for measuring a broad range of emotional and behavioral problems in children and adolescents. At the 5-year follow-up, a shortened version of the CBCL (15) was used. At the 14-year follow-up, two measures of psychopathology were available. The full CBCL was completed by the mothers, and the Youth Self-Report (YSR; 16 ), an instrument with items comparable to the CBCL, was completed by the adolescent cohort member. Total scores and scores on the two main subscales, internalizing and externalizing problems, were assessed.

Two items from the CBCL and the YSR thought problems subscale were chosen for their face validity in measuring psychotic-like experiences: “I hear sounds or voices that other people think are not there” and “I see things that other people think are not there”; participants could respond “never,” “sometimes,” or “often.”

To explore the impact of substance abuse on the variables of interest, we examined an item from the Young Adult Self-Report (17) , which was administered at the 21-year follow-up (“I use drugs other than alcohol for nonmedical purposes”).

Statistical Analyses

Analyses were performed using SAS (SAS Institute, Cary, N.C.). We used generalized linear models to examine the association between PDI score (the outcome variable) and either CBCL or YSR score (predictor variables), after adjustments for gender and age at assessment at the 21-year follow-up (because the cohort births occurred over 3 years, the actual ages at follow-up varied slightly). To provide more meaningful effect sizes for the associations, we then divided the CBCL and YSR scores into quartiles and used maximum-likelihood logistic regression to examine the association between these scores and delusional-like experiences at age 21. These analyses allowed us to examine whether the relationship was distributed evenly across the quartiles or was more prominent in the highest quartile. For predictor variables, we dichotomized the sample based on those whose scores were in the highest quartile versus those whose scores were in the lowest three quartiles.

To ascertain whether mental health problems during childhood and in adolescence were independently associated with later delusional-like experiences, the analysis was adjusted for gender and age at assessment at the 21-year follow-up. Because our previous work had found that younger members of this cohort and females were significantly more likely to have higher PDI scores (18) , gender and age were included as covariates in the analyses. We repeated the main analyses with the subgroup that reported no substance abuse.

To capture the within-individual trajectory of psychopathology across childhood and adolescence, we linked comparable scores at ages 5 and 14. For the purposes of these analyses, we were interested in adult delusional-like experiences in those cohort members who were in the top quartile on psychopathology scores at ages 5 and 14. Thus, for the 5-year and 14-year assessments, we dichotomized the cohort into those in the highest quartile (“high”) versus the lower three quartiles (“low”) based on each separate follow-up. Based on these scores, we created four discrete groups of cohort members who showed consistently high scores (high at year 5 and high at year 14); consistently low scores (low at year 5 and low at year 14); relative improvement in psychopathology (high at year 5 and low at year 14); or relative worsening in psychopathology (low at year 5 and high at year 14). We examined the association between this four-level longitudinal variable and later PDI score.

We also examined whether the two specific items related to hallucinations at age 14 were associated with PDI score at age 21. If significant associations were found, we planned secondary analyses to further examine the strength of this relationship in participants who had a high total YSR score (i.e., those with broad psychopathology in addition to hallucinations).

At the 21-year follow-up, the lifetime prevalence of psychotic disorders was assessed by trained health professionals using structured interviews, including the Composite International Diagnostic Interview (19) . Sixty cohort members were identified as having nonaffective psychoses (schizophrenia, delusional disorder, brief psychotic disorder, and schizophreniform disorder). We recently reported, on the basis of this same cohort, that childhood and adolescent psychopathology was significantly associated with adult nonaffective psychoses (8) . To exclude the influence of this subgroup, we conducted an additional planned sensitivity analysis in which these 60 cohort members were excluded from the analyses.

Attrition

There has been considerable research in recent years related to the handling of missing data in longitudinal prospective studies (20) . While sophisticated techniques such as multiple imputation are now available (21) , these methods rest on the assumption that variables or cases have been lost to follow-up in a random fashion. Because experience shows that patterns of attrition in birth cohorts are mostly nonrandom (9) , modeling exercises (i.e., “thought experiments”) can also be used to explore the robustness of the findings in response to particular scenarios.

We explored the influence of attrition using three methods. First, to examine whether psychopathology scores during childhood or adolescence (the predictor variables in this study) were differentially associated with attrition, we examined whether being lost to follow-up at age 21 was associated with quartile distributions for CBCL total score at age 5 and for YSR total score at age 14. Second, we used SAS PROC MI and MIANALYZE to explore the data under the assumption that data were missing randomly. For the multiple imputation, we included the main variables of interest (CBCL, YSR, and PDI scores) and a broad range of potential confounders that were either examined specifically in this study (age at assessment, gender, and past substance abuse) or known to be associated with attrition in this cohort (9) (birth weight and various maternal variables at first clinic visit related to age, education, marital status, mental health, and smoking). We used linear regression based on five imputed data sets. Finally, based on the assumption that the data were missing in a nonrandom fashion, we undertook post hoc modeling exercises to explore the robustness of the main findings under a set of assumptions that would be potentially damaging to the original findings.

Results

Of the original 7,223 participants, the PDI was completed by 3,617 (50%) at the 21-year follow-up. Within this subgroup, 1,709 (47.2%) were male, and maternal ethnicity was 95% white, 3% Asian, and 2% Aboriginal or Torres Strait Islander. Because the cohort was born over several years and the follow-up interviews were completed within a narrower time frame, the mean age at assessment was 20.1 years (SD=0.90; range=18–23). The mean PDI score for the sample was 5.08 (SD=3.65, modal score=3, range=0–21). The quartiles for the PDI score were scores of 2 or lower; 3 or 4; 5 to 7; and 8 and above.

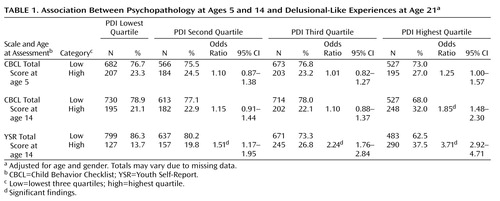

When scores were assessed as continuous variables, significant associations were observed between PDI score at age 21 and CBCL score at age 5 (F=16.99, df=1, 3231, p<0.001), CBCL score at age 14 (F=73.52, df=1, 3405, p<0.001), and YSR score at age 14 (F=263.79, df=1, 3407, p<0.0001). When scores were assessed as quartiles ( Table 1 ), there was a trend-level association between CBCL score at age 5 and PDI score at age 21 (odds ratio=1.25). Participants whose CBCL scores were in the highest quartile at age 14 were significantly more likely to have PDI scores in the highest quartile at age 21 (odds ratio=1.85). Participants whose YSR scores were in the highest quartile at age 14 were significantly more likely to have elevated delusional-like experiences at age 21. The effect size for the association between the highest quartile of the YSR score at age 14 and the highest PDI quartile (odds ratio=3.71) was nearly twice that for the highest CBCL quartile at age 14.

The association between CBCL and YSR subscale scores and adult PDI score was examined. Even after adjusting for age, gender, and illicit drug use, those who scored in the highest quartile on the internalizing or the externalizing subscales at age 5 were significantly more likely to score in the highest quartile on the PDI at age 21 (odds ratio=1.32, 95% CI=1.05–1.66, and odds ratio=1.36, 95% CI=1.09–1.70, respectively). Similar to associations seen with total scores, those whose scores were in the highest quartile on the internalizing or externalizing subscales of the CBCL and YSR at age 14 were significantly more likely to have elevated PDI scores at age 21 (data not shown).

Table 2 summarizes the trajectory of psychopathology during childhood and adolescence and delusional-like experiences at age 21. Participants whose scores were in the lowest three quartiles on the CBCL at age 5 and the YSR at age 14 were the reference group (i.e., consistently low). For those who were in the highest quartile for childhood psychopathology at age 5 but who had shifted to the lower three quartiles at age 14 (i.e., relative improvement), there was no significant association with adult delusional-like experiences. Conversely, those who scored in the lower three quartiles at age 5 but who were more symptomatic at age 14 (i.e., relative worsening) were more likely to report delusional-like experiences at age 21 (odds ratio=3.76). As predicted, the strongest association with delusional-like experiences at age 21 was observed in participants who had continuously high levels of psychopathology during childhood and adolescence (i.e., consistently high). Those who were in the highest quartile on the CBCL at age 5 and the YSR at age 14 were more than four times as likely to have high levels of delusional-like experiences in adulthood ( Figure 2 ).

a The level of psychopathology was measured by the Child Behavior Checklist (CBCL) at age 5 and the Youth Self-Report (YSR) at age 14. The cohort was dichotomized into those whose scores on these instruments were in the highest quartile (“high”) versus those whose scores were in the lower three quartiles (“low”). The level of delusional-like experiences at age 21 was measured by the Peters Delusional Inventory.

Endorsement of the two items related to hallucinations at age 14 was significantly associated with elevated PDI scores at age 21 ( Table 3 ). The more frequent the hallucinations, the stronger the association. For example, compared to those who responded “never” on the item on hearing sounds or voices that other people think are not there, those who reported “sometimes” were more than twice as likely to be in the highest quartile on PDI score at age 21 (odds ratio=2.47); those who responded “often” on this item were almost five times as likely to be in the highest PDI quartile at age 21 (odds ratio=4.84) ( Table 3 ).

We wished to explore the strength of the relationship between the items related to hallucinations and delusional-like experiences at age 14 and PDI score at age 21 in the subgroup with high levels of psychopathology at age 14 (i.e., those in the highest quartile for total YSR score). As predicted, the strength of the relationship between the variables of interest in this more disturbed subgroup was larger. For example, compared to those who reported never hearing voices, those who reported hearing voices “often” at age 14 within the high-YSR-score subgroup were nine times as likely to be in the highest PDI quartile at age 21 (odds ratio=9.24). This same pattern was seen in the other hallucination item assessed at age 14 (data not shown).

With respect to differential attrition, there was no significant association between scores on the CBCL at ages 5 and 14 or on the YSR at age 14 and being lost to follow-up at age 21 (data not shown). Based on five imputed data sets, the main findings based on linear regressions remained statistically significant (data not shown). Based on our findings linking early psychopathology with higher PDI scores at age 21, we assumed that if cohort members who were lost to follow-up had high scores on the CBCL, YSR, and PDI, then our analyses would have underestimated the effect size of the relationship. Instead, we chose to model a scenario that would be more likely to weaken the identified relationship. We assumed that cohort members who were lost to follow-up at either age 5 or age 14 were restricted to the lower quartiles of the YSR and CBCL and would have had PDI scores in the highest quartile had they remained in the cohort. With respect to the relationship between CBCL score at age 5 and PDI score at age 21, the modeled scenario resulted in a reversal of the pattern of association (modeled odds ratio=0.69, 95% CI=0.58–0.82), indicating that this particular finding was not robust to the differential attrition included in our model. In contrast, for the other variables of interest, while the effect size of the relationship decreased, the direction and statistical significance remained consistent with the actual results (CBCL score at age 14, modeled odds ratio=1.19, 95% CI=1.003–1.41; YSR score at age 14, modeled odds ratio=1.62, 95% CI=1.37–1.91).

With respect to substance use, 25.6% of the cohort reported illicit drug use. When the main analyses were repeated with the cohort members who denied illicit drug use, the effect size was reduced slightly, but the direction and significance level of the findings remained unchanged (data not shown). Finally, we repeated the main analyses, excluding the 60 participants identified as having nonaffective psychoses. There was no change in the overall pattern of results with respect to effect size or significance level (data not shown).

Discussion

We found that psychopathology as measured by the CBCL and the YSR during childhood and adolescence was associated with high levels of delusional-like experiences at age 21. For some young adults, psychotic-like experiences appeared to be evident at age 14 and were associated with increased psychopathology from at least age 5. These key results are summarized in Figure 3 . Based on this same cohort, we recently reported that an elevated CBCL score at age 5 was associated with a significantly increased risk of nonaffective psychoses in male but not female cohort members (8) . The finding that psychopathology at age 5 predicts both psychotic disorders and high PDI scores at age 21 suggests that these outcomes may share pathways with respect to etiopathogenesis. This finding is consistent with the association between childhood psychopathology and later schizophreniform psychosis (7) .

It is conceivable that childhood psychopathology could lead to greater cannabis use, which in turn could result in higher delusional-like experiences in young adults. Previous studies based on this cohort have identified an association between broad childhood psychopathology and subsequent substance use disorders during adulthood (22 , 23) . However, the association between psychopathology in childhood and delusional-like experiences in adulthood persisted in the subgroup that denied illicit drug use, suggesting that this pathway was not sufficient to account for the main finding.

With respect to the prediction of delusional-like experiences in young adulthood, the self-report measure used at age 14 (the YSR) was more informative than the comparable measure completed by the mothers at the same follow-up (the CBCL). This may reflect the normal developmental process of individuation-separation between adolescents and their parents (24) , when the cohort members may have been less likely to share emotional experiences with their parents. Other studies have also noted that adolescents rarely confide psychotic-like experiences to caregivers or clinicians (25 , 26) .

Our study also provided insights into the within-individual trajectory of psychotic-like experiences. Participants who had consistently high psychopathology between ages 5 and 14 were those most likely to have high PDI scores as young adults. Those who had relative worsening of psychopathology were also more likely to have elevated PDI scores at age 21. The study also demonstrated that, conversely, cohort members who had a relative improvement in psychopathology between ages 5 and 14 were “normalized” with respect to the endorsement of delusional-like experiences at age 21. Understanding the factors that influence these transitions could have implications from a public health perspective (e.g., interventions might be able to reduce the prevalence of delusional-like experiences).

This study has a number of important limitations. While we were able to exclude individuals with nonaffective psychoses as assessed at age 21, diagnostic instruments were not administered at ages 5 or 14. Some of the cohort members may have sought treatment for their symptoms. While we were unable to address this issue directly, we based our main analyses on a sizable subgroup of the cohort (i.e., those who scored in the top 25% on psychopathology scales) in order to focus on a general population sample rather than on those with extreme or clinical-level symptoms. In this study we focused exclusively on the antecedents of delusional-like experiences in adulthood rather than hallucinations in adulthood. We have reported elsewhere that individuals who experience delusional-like experiences are also significantly more likely to report hallucinations (18 , 25) . As in other comparable longitudinal studies of the antecedents of psychopathology (1) , the generalizability of our findings may be affected by attrition. The modeling exercises we conducted suggest that although the association between psychopathology at age 5 and PDI score at age 21 was fragile, the associations between psychopathology at age 14 and PDI score at age 21 were robust in the face of modeling. Although we cannot directly assess the validity of our modeling, we believe that the scenario we used for the modeling would be unlikely to occur. We believe it is more likely that attrition in this sample would have weakened the effect size of the association we detected—that is, it would have made the association between childhood psychopathology and adult delusional-like experiences more difficult to detect.

We have previously speculated about the biological mechanisms that may underpin the age-related decline in the prevalence of psychotic-like experiences (18) . Throughout adolescence, there is loss of gray matter from the prefrontal cortex (26) and maturation of prefrontal networks important for cognitive processing (27) . Van Os and his colleagues have proposed that psychotic-like experiences that persist into adulthood may be a reflection of delayed neurophysiological maturation (28 , 29) . With respect to the persistence of psychotic-like experiences over the course of development, dopamine-mediated endogenous sensitization warrants closer scrutiny as a potential neurobiological mechanism underpinning the developmental trajectory identified in this study (30 , 31) .

1. Welham J, Isohanni M, Jones P, McGrath J: The antecedents of schizophrenia: a review of birth cohort studies. Schizophr Bull (epub ahead of print, July 24, 2008)Google Scholar

2. Scott J, Chant D, Andrews G, McGrath J: Psychotic-like experiences in the general community: the correlates of CIDI psychosis screen items in an Australian sample. Psychol Med 2006; 36:231–238Google Scholar

3. van Os J, Linscott RJ, Myin-Germeys I, Delespaul P, Krabbendam L: A systematic review and meta-analysis of the psychosis continuum: evidence for a psychosis proneness-persistence-impairment model of psychotic disorder. Psychol Med 2009; 39:179–195Google Scholar

4. Chapman LJ, Chapman JP, Kwapil TR, Eckblad M, Zinser MC: Putatively psychosis-prone subjects 10 years later. J Abnorm Psychol 1994; 103:171–183Google Scholar

5. Verdoux H, van Os J, Maurice Tison S, Gay B, Salamon R, Bourgeois ML: Increased occurrence of depression in psychosis-prone subjects: a follow-up study in primary care settings. Compr Psychiatry 1999; 40:462–468Google Scholar

6. Dhossche D, Ferdinand R, Van der Ende J, Hofstra MB, Verhulst F: Diagnostic outcome of self-reported hallucinations in a community sample of adolescents. Psychol Med 2002; 32:619–627Google Scholar

7. Poulton R, Avshalom C, Moffitt TE, Cannon M, Murray R, Harrington H: Children’s self-reported psychotic symptoms and adult schizophreniform disorder. Arch Gen Psychiatry 2000; 57:1053–1058Google Scholar

8. Welham J, Scott J, Williams G, Najman J, Bor W, O’Callaghan M, McGrath J: Emotional and behavioural antecedents of young adults who screen positive for non-affective psychosis: a 21-year birth cohort study. Psychol Med (epub ahead of print, July 8, 2008)Google Scholar

9. Najman JM, Bor W, O’Callaghan M, Williams GM, Aird R, Shuttlewood G: Cohort profile: the Mater-University of Queensland Study of Pregnancy (MUSP). Int J Epidemiol 2005; 34:992–997Google Scholar

10. Keeping JD, Najman JM, Morrison J, Western JS, Andersen MJ, Williams GM: A prospective longitudinal study of social, psychological and obstetric factors in pregnancy: response rates and demographic characteristics of the 8556 respondents. Br J Obstet Gynaecol 1989; 96:289–297Google Scholar

11. Wing JK, Cooper JE, Sartorius N: The Measurement and Classification of Psychiatric Symptoms: An Instructional Manual for the PSE and CATEGO Programs. New York, Cambridge University Press, 1974Google Scholar

12. Peters ER, Joseph SA, Garety PA: Measurement of delusional ideation in the normal population: introducing the PDI (Peters et al Delusions Inventory). Schizophr Bull 1999; 25:553–576Google Scholar

13. Peters E, Joseph S, Day S, Garety P: Measuring delusional ideation: the 21-item Peters et al Delusions Inventory (PDI). Schizophr Bull 2004; 30:1005–1022Google Scholar

14. Achenbach TM: Manual for the Child Behavior Checklist/4-18 and 1991 Profile. Burlington, University of Vermont, Department of Psychiatry, 1991Google Scholar

15. Najman JM, Behrens BC, Andersen MJ, Bor W, O’Callaghan M, Williams GM: Impact of family type and family quality on child behavior problems: a longitudinal study. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 1997; 36:1357–1365Google Scholar

16. Achenbach TM: Manual for the Youth Self-Report and 1991 Profile. Burlington, University of Vermont, Department of Psychiatry, 1991Google Scholar

17. Achenbach TM: Manual for the Young Adult Self-Report and Young-Adult Behavior Checklist. Burlington, University of Vermont, Department of Psychiatry, 1997Google Scholar

18. Scott J, Welham J, Martin G, Bor W, Najman J, O’Callaghan M, Williams G, Aird R, McGrath J: Demographic correlates of psychotic-like experiences in young Australian adults. Acta Psychiatr Scand 2008; 118:230–237Google Scholar

19. World Health Organization: Composite International Diagnostic Interview (CIDI), version 1.0. Geneva, WHO, 1990Google Scholar

20. Kristman VL, Manno M, Cote P: Methods to account for attrition in longitudinal data: do they work? a simulation study. Eur J Epidemiol 2005; 20:657–662Google Scholar

21. Klebanoff MA, Cole SR: Use of multiple imputation in the epidemiologic literature. Am J Epidemiol 2008; 168:355–357Google Scholar

22. Hayatbakhsh MR, Mamun AA, Najman JM, O’Callaghan MJ, Bor W, Alati R: Early childhood predictors of early substance use and substance use disorders: prospective study. Aust N Z J Psychiatry 2008; 42:720–731Google Scholar

23. Hayatbakhsh MR, McGee TR, Bor W, Najman JM, Jamrozik K, Mamun AA: Child and adolescent externalizing behavior and cannabis use disorders in early adulthood: an Australian prospective birth cohort study. Addict Behav 2008; 33:422–438Google Scholar

24. Meeus W, Iedema J, Maassen G, Engels R: Separation-individuation revisited: on the interplay of parent-adolescent relations, identity, and emotional adjustment in adolescence. J Adolesc 2005; 28:89–106Google Scholar

25. Varghese D, Scott J, McGrath J: Correlates of delusion-like experiences in a non-psychotic community sample. Aust N Z J Psychiatry 2008; 42:505–508Google Scholar

26. Toga A, Thompson P, Sowell E: Mapping brain maturation. Trends Neurosci 2006; 29:148–159Google Scholar

27. Yurgelun-Todd D: Emotional and cognitive changes during adolescence. Curr Opin Neurobiol 2007; 17:251–257Google Scholar

28. Collip D, Myin-Germeys I, van Os J: Does the concept of “sensitization” provide a plausible mechanism for the putative link between the environment and schizophrenia? Schizophr Bull 2008; 34:220–225Google Scholar

29. Cougnard A, Marcelis M, Myin-Germeys I, De Graaf R, Vollebergh W, Krabbendam L, Lieb R, Wittchen H, Henquet C, Spauwen J, van Os J: Does normal developmental expression of psychosis combine with environmental risk to cause persistence of psychosis? a psychosis proneness-persistence model. Psychol Med 2007; 37:513–527Google Scholar

30. Kapur S: Psychosis as a state of aberrant salience: a framework linking biology, phenomenology, and pharmacology in schizophrenia. Am J Psychiatry 2003; 160:13–23Google Scholar

31. Featherstone RE, Kapur S, Fletcher PJ: The amphetamine-induced sensitized state as a model of schizophrenia. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry 2007; 31:1556–1571Google Scholar