The Use of Animal Models in Psychiatric Research and Treatment

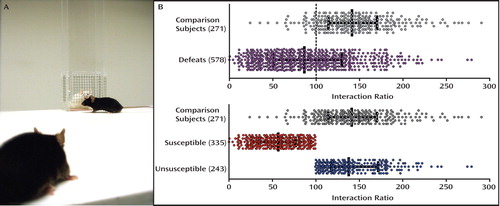

For psychiatric illnesses, animal models are essential to study disease mechanisms and develop novel treatment approaches, particularly given the very limited availability of the human brain for basic experimentation. These models must incorporate behaviors that resemble the human condition, predictably respond to available clinical treatments, be based on known (or strongly hypothesized) etiological factors, and be molecularly congruent with disease markers in humans. Our animal model was motivated by the following clinical observation: Upon exposure to the same stressful stimulus, human responses vary; some humans develop clear psychiatric conditions (e.g., depression, posttraumatic stress disorder [PTSD]), whereas other resilient individuals function normally. We set out to model this phenomenon of “resilience” by employing a chronic social defeat paradigm. An episode of social defeat was accomplished by forcing a mouse to intrude into space that was “territorialized” by a larger mouse of a more aggressive type, leading to an agonistic encounter that ultimately resulted in intruder subordination. Using a quantitative social interaction task (panel A), such repeated defeat encounters produced a wide distribution in measures of social interaction (panel B). Defeated mice were segregated into those that displayed clear deficits in social interaction (“susceptible”) and those that did not (“unsusceptible” or resilient). Through such segregation, we discovered that only susceptible mice displayed several mouse analogs of human depressive behavior (anhedonia, circadian abnormalities, weight loss, and sensitized responses to abused drugs). An elevation of brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) in the nucleus accumbens (NAc) was uniquely associated with the susceptible phenotype. Moreover, the reduction of BDNF in the ventral tegmental area (VTA) (a region in the brain that projects directly to the NAc) using genetically modified mice, as well as the inhibition of neuronal activity in the VTA, blocked BDNF and depression-like behaviors in socially defeated mice. To confirm the relevance of this model to human depression, we demonstrated elevations of BDNF in postmortem human NAc in depressed subjects relative to comparison subjects. We also showed that a naturally occurring impairment in activity-dependent BDNF release (BDNF G196A, val66met) promotes resilience to social defeat.

Figure 1. Following repeated social subordination, defeated mice (black) are tested for their display of social avoidance toward an unfamiliar aggressor (white mouse in cage [panel A]). This photograph serves to illustrate how some mice adopt a “freezing” posture and position themselves at a distance (“susceptible”), while others actively explore and interact with the aggressor (“unsusceptible”). Such a phenotypic classification is long lasting and cannot be explained by inherent differences in anxiety-related behavior. Furthermore, social avoidance in susceptible mice is reversed by the chronic (but not acute) administration of antidepressant agents. Such heterogeneity in response to social defeat can be quantified using measures such as the “interaction ratio,” a representation of a relative preference for a social cue (panel B, error bars: mean ± interquartile range). Images adapted/modified with permission from Krishnan et al., “Molecular Adaptations Underlying Susceptibility and Resistance to Social Defeat in Brain Reward Regions” [Cell 2007; 131:391–404]). Copyright © Cell.

The application of this mouse model provides an opportunity to look further at molecular and behavioral correlates of vulnerability and resilience to stress. A deeper understanding of mechanisms imparting a resilient phenotype can promote the development of prophylactic approaches to depression following significant stress as well as the design of pharmacological and behavioral interventions to prevent stress-related psychiatric conditions.