Issues for DSM-V: Adding Problem Codes to Facilitate Assessment of Quality of Care

Efforts to improve the quality of medical care (1) —and mental health and substance use care in particular (2) —will be a top priority in the next decade, and incentives are being implemented to reward those clinicians who can demonstrate the delivery of quality care (3 – 5) . In order to minimize burden, automated methods for performance measurement need to be developed. For each psychiatric diagnosis (e.g., major depressive disorder), there are a range of assessment issues that must be considered (e.g., Is suicidal ideation present?) and a range of problems that must be managed (e.g., depressed mood, social withdrawal, job loss). Administrative databases, however, typically include only “codable” information, such as ICD-9-CM diagnostic codes, CPT codes, and pharmacy records. It is often not possible to determine whether a particular treatment was appropriate, since interventions are not aimed at diagnoses per se but at particular symptoms or problems. For example, given only the diagnosis of schizophrenia and the fact that an antidepressant was prescribed, there is no way to determine whether the treatment was appropriate in the absence of other indicators of the presence of depressed mood. Furthermore, the lack of CPT codes for assessing suicidal ideation and other critical symptoms makes it impossible to determine whether such assessments were included in the evaluation process.

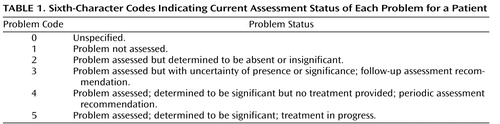

Expanding DSM-V to include a comprehensive list of standardized problem codes could help to facilitate automated quality care assessment. These codes would include a mixture of target symptoms (e.g., risk of self-harm, impulsivity) and psychosocial and environmental problems that require intervention (e.g., homelessness, marital discord) and would be used to indicate problems that are a focus of treatment as well as potential problems that should be assessed (e.g., homicidal ideation in a patient with acute exacerbation of schizophrenia). Given that DSM-V will likely use ICD-10-CM diagnostic codes (expected to be adopted by the U.S. Government before 2012), the proposed problem list codes would be adapted from the ICD-10-CM R codes (symptoms and signs not elsewhere classified) and Z codes (factors influencing health status). The current assessment status for each problem would be indicated in the sixth character ( Table 1 ). For example, the problem list codes for a homeless patient with schizophrenia who presents with command hallucinations, avolition, and a recent history of violence might be as follows: F20.0, paranoid schizophrenia (R44.005, auditory hallucinations; R45.605, violent behavior; R45.304, avolition; R45.852, suicidal ideation; Z59.005, homelessness).

This coding indicates that treatment is currently underway for the auditory hallucinations and violent behavior, that avolition was noted but no treatment was currently provided, that suicidal ideation was assessed and found to be absent, and that plans are under way to arrange for housing. Advantages of this proposal include the provision of standardized codes corresponding to what clinicians actually treat and the provision of a mechanism to indicate that a problem was assessed but determined to not require clinical attention (i.e., codes 2–4).

Practical considerations would likely limit successful implementation to electronic health record systems in which selection of problem codes could be facilitated by presenting pop-up menus displaying those problem codes most commonly associated with a particular diagnosis. Such diagnosis-specific pop-up problem lists could be constructed empirically by examining databases of problem-oriented medical records. Financial rewards in the form of higher reimbursement rates would also likely be necessary to incentivize clinicians to take these extra steps. Insurers would be motivated to collect such data, in order to demonstrate to purchasers that they have high quality clinical networks, and to have mechanisms in place to improve quality. Medicare has already implemented the Physician Quality Reporting Initiative providing a financial bonus to physicians who report coded information on quality of care (6) .

1. Institute of Medicine Committee on Quality of Health Care in America: Crossing the Quality Chasm: A New Health System for the 21st Century. Washington, DC, National Academies Press, 2001Google Scholar

2. Institute of Medicine Committee on Crossing the Quality Chasm: Adaptation to Mental Health and Addictive Disorders: Improving the Quality of Health Care for Mental and Substance-Use Conditions. Washington, DC, National Academies Press, 2006Google Scholar

3. Ettner S, Schoenbaum M: The role of economic incentives in improving the quality of mental health care, in Elgar Companion to Health Economics. Edited by Jones AM. Cheltenham, United Kingdom, Edward Elgar Publishing, 2006Google Scholar

4. Rosenthal B, Landon B, Normand S, Frank R, Ahmad T, Epstein A: Employers’ use of value-based purchasing strategies. JAMA 2007; 298:2281–2299Google Scholar

5. Charland K: Pay for performance comes to Medicare in 2009. Healthc Financ Manage 2007; 61:60–64Google Scholar

6. Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services: Physician Quality Reporting Initiative. http://www.cms.hhs.gov/pqri/ (accessed 2008)Google Scholar