Teaching Supportive Psychotherapy to Psychiatric Residents

“Mr. A” is a 45-year-old married teacher pursuing a doctorate in education at a local university. Although he completed the course work without difficulty, he feels “stuck” and unable to move ahead with his dissertation. In this setting, his chronic, low-grade depression has worsened and now includes profound feelings of humiliation, despair, and hopelessness, near-panic-like anxiety, insomnia, and trouble functioning at his teaching job. His wife urges him to get help after he begins to talk about an impulse to jump from their balcony.

Mr. A went through a period of depression, heavy drinking, and narcotics addiction in his early 20s, after a sports-related injury forced him to drop out of college. He was referred to a psychiatrist but felt the psychotherapy had been “too open-ended” and “a waste of time and money.” With his wife’s support, he managed to stop drinking and using narcotics and has remained sober ever since. He went on to become a valued high school teacher and coach, receiving several medals for excellence in teaching. Later he was awarded a full scholarship to an Ivy League university, where he earned a master’s degree in education. Asked about any other events in his life that may have contributed to his current depression, Mr. A mentions that his father was a heavy drinker who used to chase him around the house with a loaded gun when drunk. The father was diagnosed with cancer shortly after Mr. A started the doctoral program and died after a brief illness, during which Mr. A lived with and helped care for him.

The second-year resident to whom Mr. A has been assigned admits to her supervisor that she is already having a “sinking feeling” about Mr. A. He says he is too depressed to talk about his future, much less make any important decisions about his life. He is also reporting debilitating side effects from the antidepressant she has prescribed and has warned her that he is “sensitive” to most drugs. The resident describes him as “not just stuck, but sticky—I feel like I’m wading in molasses.” She finds herself wanting to end sessions early but tends to run late because of his last-minute reports of alarming physical symptoms or fleeting thoughts about “blowing his brains out.” The resident has noticed that although Mr. A is relentless in his protestations of worthlessness, he likes to wear a sweatshirt from the Ivy League school he attended, and he enjoys acting as an auxiliary therapist in groups—“a pretty good one, too.” The resident adds ruefully, “I guess he just needs support, but we haven’t had that course yet. What do you suggest?”

What Is Supportive Psychotherapy?

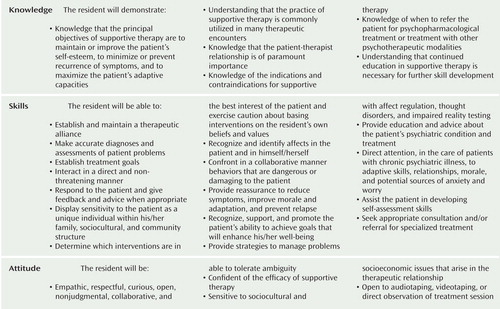

Formerly regarded as the “Cinderella of psychotherapies” (1) and requiring no special training or abilities beyond common sense, interpersonal skills, and a capacity for empathy, supportive psychotherapy has over the past several decades gradually assumed a position of greater importance within the didactic curriculum of residency training programs in psychiatry. The Accreditation Council on Graduate Medical Education’s Residency Review Committee for Psychiatry now requires training directors to certify that graduating residents have achieved “competency” in supportive psychotherapy along with four other areas of psychotherapy (brief therapy, cognitive-behavioral therapy, combined psychotherapy and psychopharmacology, and psychodynamic therapy). As a guide for program directors, the American Association of Directors of Psychiatric Residency Training developed sample “competencies” for each form of therapy, including, inter alia, five “facts,” 15 “skills,” and three “attitudes” related to supportive therapy ( Figure 1 ). Although there is a growing literature on attaining and assessing psychotherapy competency in residency training (3 – 10) , few publications provide guidelines on how supportive psychotherapy should be taught (11 – 13) , and there is a lack of consensus on what exactly we want residents to be learning. From their perspective, residents face the daunting challenge of trying to integrate contrasting and sometimes mutually exclusive perspectives.

a Adapted from Pinsker et al. (2).

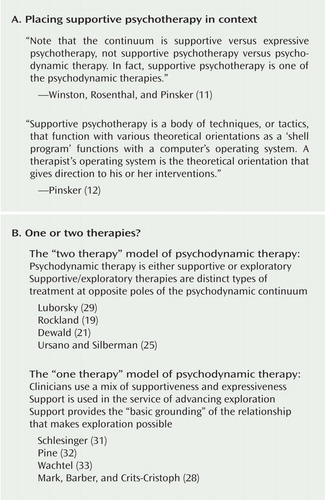

While most authors regard supportive therapy as a form of psychodynamic or psychoanalytically oriented psychotherapy (14 – 22) , some appear to make a distinction between psychodynamic and supportive therapies, implying if not stating unambiguously that supportive therapy is not psychodynamic (23 – 25) . Others argue that supportive therapy should be conceptualized as an “atheoretical” set of techniques not derived from any one overarching model of personality development or psychopathology ( Figure 2 , part A) (12 , 26 , 27) . Even among proponents of the view that supportive therapy, like exploratory (or expressive) psychotherapy, is conceptually rooted in psychodynamic theory, there is lingering controversy about whether these approaches are dissimilar enough in basic goals, strategies, and techniques to be considered two distinct types of psychotherapy at opposite poles of a “psychodynamic continuum” extending from supportive psychotherapy to psychoanalysis (19 , 21 , 28 – 30 ). Others suggest that there is no such thing as supportive psychotherapy as a distinguishable kind of psychodynamic treatment. Instead, support is seen as a dimension of all dynamic psychotherapy, present to a greater or lesser extent depending on the particular context, problems, and needs of the person ( Figure 2 , part B) (17 , 20 , 21 , 31 , 32) .

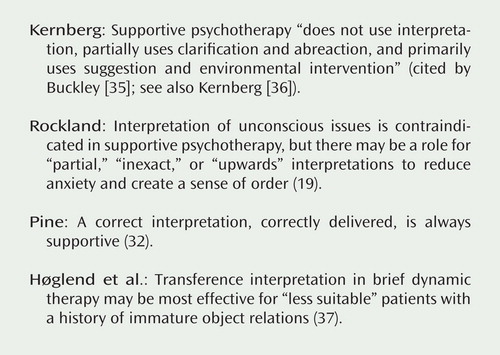

In addition to these discrepancies in theory, basic differences of opinion exist about the indications for supportive therapy, ranging from the classical view that supportive therapy should be prescribed for “lower-functioning” patients considered unsuitable for exploratory approaches to the position that supportive treatment should be the default treatment of choice for all patients regardless of the severity of their psychopathology (34) . There are also lingering disputes about the “correct” methods of supportive therapy, such as the role for interpretation ( Figure 3 ) (12 , 15 , 19 , 32) . The mainstream clinical thinking that interpretive approaches and transference work are generally reserved for patients with “good ego strength” must also be reconciled with recent research findings suggesting that transference interpretation in brief dynamic therapy may be most effective for the so-called less suitable patients who have a history of immature object relations (37) .

“Think Psychoanalytically” in Providing Support

As difficult as it has been to reach a consensus on the body of knowledge and skills that we hope to impart to our trainees, even less is known about what constitutes effective training in supportive psychotherapy for psychiatric residents. Some authors have suggested that supportive therapy should be taught as a body of generic techniques compatible with a variety of different theoretical perspectives (e.g., psychodynamic, cognitive-behavioral, and interpersonal) (12 , 13 , 34) . Yet, as one of these authors readily admits, “psychodynamic positions” are embodied in the clinical vignettes he offers to illustrate the mechanics of what to say in supportive therapy ( 12 , p. 4). Much of the literature on supportive psychotherapy relies heavily on the language of psychoanalysis in describing characteristic techniques, such as “improving ego functions,” “minimizing the focus on transferential material,” and “confronting maladaptive defenses,” thus assuming some familiarity with ego-psychological psychodynamic theory.

Without some introduction to core psychoanalytic concepts, beginning psychotherapists can hardly be expected to understand what it means to “manage” or “manipulate” the transference in supportive therapy and how this differs from “interpreting” the transference in a more exploratory treatment, let alone which patients under what circumstances require such “management” and why. Without working hypotheses about the unconscious motives, feelings, and conflicts underlying a person’s distress, it is also difficult to see how they would have any basis for predicting what would be supportive or nonsupportive for the individual patient at any given moment in the treatment (16) . It seems akin to asking novice pilots to fly in the dark without maps or instruments.

Asked why Mr. A is seeking help now, the resident suggests that he is “a narcissist in the middle of a midlife crisis” and probably felt mortified when he realized that he was never going to write the “perfect” dissertation. She also speculates that unresolved anger about his difficult childhood may have been stirred up by his father’s death. But when she asked about his childhood, Mr. A complained that he had already “been there, done that” in his prior psychotherapy and added irritably, “Enough rugs have been pulled out from under me lately to explain my funk without dredging up my childhood.” Despite nagging feelings that she was “ignoring the elephant in the room,” the resident shifted gears and tried to boost Mr. A’s morale by expressing optimism about his potential for achieving his career goals. With a trace of condescension in his voice, Mr. A responded icily, “I’m going to need a lot more than cheerleading, honey.”

Trainees also need to understand the differences between thinking psychoanalytically in providing support and acting like a psychoanalyst. Residents often feel compelled to explore the emotional “hot spots” in the person’s history (such as Mr. A’s history of childhood trauma). They have trouble understanding how a person can change in meaningful and enduring ways if these more conflict-laden issues are “supportively bypassed” in favor of the “here-and-now” problems that are consciously on the patient’s mind. They can certainly support their patients’ wish to know and understand more about themselves, but at the person’s own pace, and at a comfortable depth. One of the cardinal rules of supportive therapy is “Do not say everything you know, only what will be helpful.” The same might be said about teaching any form of psychotherapy.

What Needs Support?

For the sake of clarity and because it is a model that is easier for the beginner to assimilate, supportive therapy is often taught as a “pure culture” form of dynamic therapy with its own distinct goals, methods, and techniques and is differentiated as much as possible from more exploratory approaches to highlight their theoretical and technical differences (21 , 22) . Perhaps for this reason, many residents believe that psychodynamic psychotherapy must be either exploratory or supportive, and that where there is support, there cannot be exploration. Schlesinger (31) has questioned the validity of such dichotomous thinking and has argued persuasively that truly useful prescriptions for treatment should be explicit about what aspects of a person’s emotional and mental functioning need “support.” The therapist can then determine what kind and amount of support will be required as the person begins to explore the problems that brought him into treatment (31) .

What is “supported” in supportive psychotherapy is not simply a sense of safety, self-esteem, or hope—all of which are priorities early in treatment—but deficient psychological capacities or “ego functions.” Thus, the supportive therapist helps the patient see things more clearly by supporting reality testing, tactfully challenging unrealistic ideas, and demonstrating more effective, less costly ways of defending while supporting adaptive defenses. Additionally, it is the supportive therapist’s role to examine with the patient the possible consequences of one path of action or another. The supportive therapist helps the person tolerate and regulate a wider range of affects; limits self-destructiveness and impulsivity; helps the person talk about his inner life in more productive ways by sharpening vague speech; and helps him get along better with others by strengthening control over socially unacceptable behavior and encouraging healthier ways of relating to others, both in and outside of therapy (16) . Residents should be encouraged to ask themselves what their patients’ strengths are as well as their vulnerabilities. Which ego functions are basically intact and which are deficient or failing? What circumstances in the person’s treatment or in his life call for more supportive interventions, and at what point might these supports no longer be required?

Like most people, Mr. A presents with a mix of personality strengths and vulnerabilities. His past history includes significant emotional trauma in childhood and suggests “ego weaknesses” in a number of areas of functioning, including impulse control, affect regulation, defensive functioning, and self-esteem. He has also recently lost his father and is currently in the midst of a life crisis—all of these well-recognized indications for adopting a more “supportive” approach. At the same time, he has numerous strengths for which he has trouble giving himself credit: he is intelligent, a good athlete and teacher, a loving husband and father, and a good auxiliary therapist in groups. He has demonstrated a capacity for perseverance and discipline in his work despite long-standing internal conflicts and has maintained an enduring marriage with a woman he experiences as loving and supportive, suggesting a capacity for mature relationships. In the balance, he seems to be a man who, over the course of his life and in the context of a supportive relationship with an affirming woman, has achieved a generally good level of ego-functioning, which has now been temporarily overwhelmed in the setting of major depression, setbacks in his career, and his father’s death.

Provide a Holding Environment

Despite differences of opinion about theory and technique, there is general agreement that the main priority in supportive psychotherapy is to build a “holding environment” and to foster the therapeutic alliance. Whether because of inexperience, lack of confidence, or perhaps mistaken application of what they have heard about Freud’s “blank screen” model of the therapist-patient relationship, residents sometimes err on the side of being too silent, passive, and opaque with patients they are treating supportively. Although they intuitively understand that the first order of business in any psychotherapy is to establish an atmosphere of emotional safety and trust, they tend to be insufficiently mindful of the fact that this is especially crucial, and usually harder to achieve, with more fragile patients. As Appelbaum has emphasized (17 , 18) , whereas basically healthy people are able to maintain their sense of self-worth in relation to the therapist and to weather the inevitable ruptures that occur in the treatment relationship, more vulnerable patients have special sensitivities that make it harder for them to shrug off what they perceive as the therapist’s blunders and empathic failures. They are more prone to misinterpreting things the therapist says and does and tend to feel anxious, demeaned, or mistrustful if the therapist maintains an overly neutral, abstaining, and anonymous stance.

Residents learning about supportive psychotherapy need to be encouraged to work actively from the very beginning to ensure that their patients’ feelings of anxiety, shame, envy, anger, and despair are kept within tolerable bounds and to pay continuous attention to the person’s self-esteem (11) . Although transference is neither fostered nor focused on in supportive psychotherapy, residents should be told to keep a watchful eye on the “prevailing climate” in the relationship. They should monitor how the person is feeling about himself, the therapist, and the treatment and intervene quickly to repair (rather than explore) any signs of rupture in the alliance. This should also be the supervisor’s primary concern.

Recognizing that the resident feels demeaned and defeated, the supervisor tries to help her find some basis for liking Mr. A. He begins by empathizing with her feelings of frustration and dread and acknowledging the ways in which Mr. A appears to thwart her efforts to help him (“You want to help, but he will not let you”). He shares personal anecdotes about similarly “resistant” patients he has treated and offers a few tricks of the trade for ending sessions with Mr. A on time. The supervisor then quietly comments on Mr. A’s courage in weathering his father’s terrorizing behavior and expresses admiration for his obvious strengths—the durable and loving nature of his relationship with his wife, his resolve to provide for his son the safe haven he never had, his basic toughness in holding things together as well as he has, and his incentive to continue working in spite of his depression. As well as his life has turned out, apparently it is not enough. Another man in his shoes might have been content to rest on his laurels, but not Mr. A. The supervisor adds that in his experience it is typical for someone who is seriously depressed to forget that he has ever had periods of better functioning, to overlook the things in his current life that are actually going well, and to have trouble imagining that anything will ever alleviate the pain. The supervisor also reminds the resident that letting herself become affected by Mr. A’s sense of urgency and panic will probably only increase his “resistance.” Borrowing a page from the manual on cognitive therapy, the supervisor models a more “decatastrophizing” approach (“What would be the worst outcome if he never finished the dissertation? What would be so terrible about that?”).

“Be Yourself”

Residents have usually heard the oft-quoted injunction to “be yourself” in conducting supportive psychotherapy—more responsive, conversational, “real,” and “self-revealing”—but typically receive little guidance about how responsive and self-revealing they should be, about what, and why. They tend to talk about providing support with a hint of guilt or shame, as if they have broken some inviolable rule of therapist conduct. The “proper conduct” of the supportive psychotherapist is a teachable interpersonal style best modeled in the supervisory relationship. Just as residents learn over time to offer their own lived experience as an “object lesson” for the person they are treating supportively, supervisors should feel free to share their own learning process, including any gaffes, confusion, and embarrassing moments they may have experienced along the way. Being open with residents about our own struggles, rather than pretending to be omniscient “gurus” with secret knowledge and abilities far beyond those of mortal man, helps to demystify the process of becoming a competent psychotherapist (E. Auchincloss, personal communication, 2007). Residents generally enjoy these confessional accounts and tend to respond with greater openness about their own perceived mistakes, uncertainty, and apprehensions (38) . Sharing examples from our own work also gives residents a more accurate picture of the complexity and ambiguity of the moment-to-moment real-world clinical decisions we typically face in the “middle ground” of the psychodynamic continuum where most psychotherapy is conducted and enables them to view these decisions in a more realistically nuanced manner. The supervisor’s approach has much in common with the “pedagogical and personal” manner of the supportive psychotherapist as described by Schafer (39) .

Do Just Enough

Like the people they are trying to help, residents often feel overwhelmed by the apparent enormity of the task they face and may feel responsible for bringing about a total life overhaul in a relatively brief period of time. They need to be reminded that small improvements can lead to bigger changes and that setting overly ambitious goals will only increase the likelihood of failure. Doing “just enough” is good enough—just enough to reduce anxiety, build self-esteem, instill hope, support deficient psychological functions, and improve overall functioning. Within these general parameters, the resident should be encouraged to enlist the patient’s input in clarifying what sort of help he was hoping the therapist might provide and defining specific and achievable objectives for their work together. Residents also need to be cautioned about the possible “ego weakening” effects of blindly applying too many “supportive” interventions often assumed to be at the core of supportive psychotherapy. These include offering advice, feedback, or solutions for problems without first actively encouraging the person to examine his options, consider alternative strategies, and weigh their relative merits and drawbacks. Residents should be alerted that they will need to modify their approach over time as the person and his circumstances change. It might be appropriate for the resident to offer limited advice early in the treatment, but not later when the person is in a position to make decisions for himself.

The supervisor suggests that Mr. A is a proud man—justifiably so—and seems to feel humiliated about his need for help. He suggests that the resident should view her role less as a cheerleader (which Mr. A seems to experience as insincere and patronizing) and more as a “hands-off” coach, ready to “spot” him if he falters and offering a few pointers here and there as needed, but implicitly expressing her faith in his ability to call the plays and manage the game on his own. The supervisor wonders aloud whether Mr. A’s trouble acknowledging his strengths and accepting praise might be “the depression talking,” and he asks the resident if she thinks Mr. A’s pride would allow him to receive just a little psychoeducation about the cognitive symptoms of depression. Perhaps he might then be more willing to retry the antidepressant he so clearly needs, particularly if she assures him that it will be started at a minuscule dose and increased very gradually. At the same time, the supervisor cautions the resident not to oversell the relief an antidepressant is likely to provide (contrary to the approach she might take with a dependent patient who is looking for a benevolent parent to pull him out of his depression). She should take care to attribute any improvements along the way to Mr. A’s own efforts rather than medication effects. While avoiding easy reassurances, she should continue to gently and tactfully challenge his distorted beliefs about his incompetence, quietly comment on the ways Mr. A has helped himself in the past, and compliment him for his achievements, such as his helpful contributions in group and his efforts to keep up with his son’s hockey team in spite of feeling bad. In short, the supervisor models for the resident what it means to truly provide support—conveying an accurate understanding of the person’s predicament, being empathic and warmly accepting, showing respect for and interest in them as a person, unobtrusively bolstering morale, encouraging mastery, and maintaining realistic hope for two.

Conclusion

It is important for residency training programs to reach a consensus about the body of knowledge and skills we hope to impart to our trainees about supportive psychotherapy and to establish some uniformity in how it is taught, if only to provide residents with a more coherent training experience. In the absence of agreed-on guidelines, teaching approaches vary significantly even within the same training program, and residents can have the bewildering experience of being taught one perspective in didactic courses on supportive psychotherapy and another by the faculty member supervising their clinical work. In a recent survey of chief residents of psychiatric residency programs, about one-quarter expressed some concerns about the faculty preparedness to teach and assess psychotherapy competencies (40) . Falender and colleagues (41) stressed the need for faculty training in psychotherapy supervision and suggested developing “supervision competencies” to ensure that faculty are prepared to provide adequate teaching and professional development for their trainees.

There is a trend toward teaching only evidence-based forms of psychotherapy with “scientifically proven efficacy” in residency training programs (42 , 43) . In some programs, Mr. A would have been offered interpersonal or cognitive-behavioral therapy, both of which have established efficacy in the treatment of depression. Supportive therapy has not been sufficiently well defined in a manual or tested in controlled clinical trials to be considered evidence based. Some authors have suggested that training residents to adhere consistently to empirically supported techniques leads them to oversimplify the complexity of real-world clinical problems, interferes with their attunement to the individual person’s needs, and curtails the flexibility and spontaneity that characterize truly competent psychotherapists (44 , 45) . Even master therapists from a particular school of treatment are flexible in their approach with patients and freely borrow techniques from different theoretical models. When Beck was videotaped doing cognitive therapy, it became apparent that he often deviated from the technique prescribed by his own manual ( 44 , pp. 8–9). This observation has led some authors to suggest that what needs to be identified is not empirically supported treatments but empirically supported psychotherapists(45) .

In the real world of everyday clinical practice, seasoned psychodynamic therapists use a mix of supportiveness and expressiveness matched to the particular needs of the individual patient at specific moments in the treatment. The most effective clinicians are those who are able to improvise and switch strategies flexibly in the immediate clinical moment. Learning to apply psychotherapeutic techniques in this intuitive, flexible, and psychodynamically informed way is not readily taught in manuals, and it mostly requires tincture of time, clinical experience, and personal maturation. As supportive psychotherapy teachers, we should remain ambitious about what our trainees can learn but realistic that we are all mostly self-taught as therapists. Most of what our residents will need to know (including how to undo some of the bad habits they have learned in training) will be acquired experientially long after they have graduated.

1. Sullivan PR: Learning theories and supportive psychotherapy. Am J Psychiatry 1971; 128:119–122Google Scholar

2. Pinsker H, Mellman L, Beresin E, Goldberg D, Misch D, Ascherman L: AADPRT Supportive Therapy Competencies. Lebanon, Pa, American Association of Directors of Psychiatric Residency Training, November 2001Google Scholar

3. Yager J, Mellman L, Rubin E, Tasman A: The RRC mandate for residency programs to demonstrate psychodynamic psychotherapy competency among residents: a debate. Acad Psychiatry 2005; 29:339–349Google Scholar

4. Manring J, Beitman BD, Dewan MJ: Assessing residents’ competence in psychotherapy. Acad Psychiatry 2004; 27:145–148Google Scholar

5. Mellman LA, Beresin E: Psychotherapy competencies: development and implementation. Acad Psychiatry 2003; 27:149–153Google Scholar

6. Mullen LS, Rieder RO, Glick RA, Luber B, Rosen PJ: Testing psychodynamic psychotherapy skills among psychiatric residents: the Psychodynamic Psychotherapy Competency Test. Am J Psychiatry 2004; 161:1658–1664Google Scholar

7. Markowitz JC: Teaching interpersonal psychotherapy to psychiatric residents. Acad Psychiatry 1995; 19:167–173Google Scholar

8. Yager J, Bienenfeld D: How competent are we to assess psychotherapeutic competence in psychiatric residents? Acad Psychiatry 2003; 27:174–181Google Scholar

9. Sudak DM, Beck JS, Wright J: Cognitive behavioral therapy: a blueprint for attaining and assessing psychiatry resident competency. Acad Psychiatry 2003; 27:154–159Google Scholar

10. Lichtmacher J, Eisendrath SJ, Haller E: Implementing interpersonal psychotherapy in a psychiatry residency training program. Acad Psychiatry 2006; 30:385–391Google Scholar

11. Winston A, Rosenthal RN, Pinsker H: Introduction to Supportive Psychotherapy. Washington, DC, American Psychiatric Publishing, 2004Google Scholar

12. Pinsker H: A Primer of Supportive Psychotherapy. Hillsdale, NJ, Analytic Press, 1997Google Scholar

13. Pinsker H: The role of theory in teaching supportive psychotherapy. Am J Psychother 1994; 48:530–542Google Scholar

14. Perry S, Frances A, Klar H, Clarkin J: Selection criteria for individual dynamic psychotherapies. Psychiatr Q 1983; 55:3–16Google Scholar

15. Winston A, Pinsker H, McCullough L: A review of supportive psychotherapy. Hosp Comm Psychiatry 1986; 37:1105–1114Google Scholar

16. Rockland LH: Psychoanalytically oriented supportive therapy: literature review and techniques. J Am Acad Psychother 1989; 17:451–462Google Scholar

17. Appelbaum AH: Supportive psychotherapy, in The American Psychiatric Publishing Textbook of Personality Disorders. Edited by Oldham JO, Skodol AE, Bender DS. Washington, DC, American Psychiatric Publishing, 2005, pp 335–346Google Scholar

18. Appelbaum AH: Supportive psychoanalytic psychotherapy for borderline patients: an empirical approach. Am J Psychother 2006; 66:317–332Google Scholar

19. Rockland L: Exploratory/supportive therapies seen as polar ends of dynamic therapy. Psychiatr Times, July 1990, pp 32–34Google Scholar

20. De Jonghe F, Rijnierse P, Janssen R: Psychoanalytic supportive psychotherapy. J Am Psychother Assoc 1994; 42:421–446Google Scholar

21. Dewald PA: Principles of supportive psychotherapy. Am J Psychother 1994; 48:505–518Google Scholar

22. Werman D: Technical aspects of supportive psychotherapy. Psychiatr J Univ Ott 1981; 6:153–160Google Scholar

23. Crown S: Supportive psychotherapy: a contradiction of terms? Br J Psychiatry 1988; 152:266–269Google Scholar

24. Hellerstein DJ, Rosenthal RN, Pinsker H, Samstag LW, Muran JC, Winston A: A randomized prospective study comparing supportive and dynamic therapies: outcome and alliance. J Psychother Pract Res 1998; 7:261–271Google Scholar

25. Ursano RJ, Silberman EK: Psychoanalysis, psychoanalytic psychotherapy, and supportive psychotherapy, in Essentials of Clinical Psychiatry. Edited by Hales RE, Yudofsky SC. Washington, DC, American Psychiatric Publishing, 2004, pp 889–914Google Scholar

26. Novalis PN, Rojcewicz SJ, Peele R: Clinical Manual of Supportive Psychotherapy. Washington, DC, American Psychiatric Press, 1993Google Scholar

27. Aviram RB, Hellerstein DJ, Gerson J, Stanley B: Adapting supportive psychotherapy for individuals with borderline personality disorder who self-injure or attempt suicide. J Psychiatr Pract 2004; 10:145–155Google Scholar

28. Mark DG, Barber JP, Crits-Christoph P: Supportive-expressive therapy for chronic depression. J Clin Psychol 2003; 59:859–872Google Scholar

29. Luborsky L: Principles of Psychoanalytic Psychotherapy: A Manual for Supportive-Expressive Treatment. New York, Basic Books, 1984Google Scholar

30. Luborsky L, Crits-Christoph P: Understanding Transference: The CCRT Method. New York, Basic Books, 1990Google Scholar

31. Schlesinger HJ: Diagnosis and prescription for psychotherapy. Bull Menninger Clin 1969; 33:269–278Google Scholar

32. Pine F: Supportive psychotherapy: a psychoanalytic perspective. Psychiatr Ann 1986; 16:526–529Google Scholar

33. Wachtel P: Therapeutic Communication: Principles and Effective Practice. New York, Guilford Press, 1993Google Scholar

34. Hellerstein DJ, Pinsker H, Rosenthal RN, Klee S: Supportive psychotherapy as the treatment model of choice. J Psychother Pract Res 1994; 3:300–306Google Scholar

35. Buckley P: Supportive psychotherapy: a neglected treatment. Psychiatr Ann 1986; 16:515–533Google Scholar

36. Kernberg OF: Supportive psychotherapy with borderline conditions, in Problems in Psychiatry. Edited by Cavenar JO, Brodie HK. Philadelphia, Lippincott, 1982, pp 180–202Google Scholar

37. Høglend P, Amlo S, Marble A, Bøgwald K-P, Sørbye Ø, Sjaastad MC, Heyerdahl O: Analysis of the patient-therapist relationship in dynamic psychotherapy: an experimental study of transference interpretations. Am J Psychiatry 2006; 163:1739–1746Google Scholar

38. Bender E: Gabbard explains dos and don’ts of teaching psychotherapy. Psychiatr News, April 15, 2005, p 30Google Scholar

39. Schafer R: Talking to patients in psychotherapy. Bull Menninger Clin 1974; 38:503–515Google Scholar

40. Khurshid KA, Bennett JI, Vicari S, Lee KL, Broquet KE: Residency programs and psychotherapy competencies: a survey of chief residents. Acad Psychiatry 2005; 29:452–458Google Scholar

41. Falender CA, Cornish JA, Goodyear R, Hatcher R, Kaslow NJ, Leventhal G, Shafranske E, Sigmon ST, Stoltenberg C, Grus C: Defining competencies in psychology supervision: a consensus statement. J Clin Psychol 2004; 60:771–785Google Scholar

42. Weissman MM, Sanderson WC: Promises and problems in modern psychotherapy: the need for increased training in evidence based treatments, in Modern Psychiatry: Challenges in Educating Health Professionals to Meet New Needs. Edited by Hamburg B. New York, Josiah Macy Foundation, 2002Google Scholar

43. Weissman MM, Verdeli H, Gameroff MJ, Bledsoe SE, Betts K, Mufson L, Fitterling H, Wickramaratne P: National survey of psychotherapy training in psychiatry, psychology, and social work. Arch Gen Psychiatry 2006; 63:925–934Google Scholar

44. Binder JL: Key Competencies in Brief Dynamic Psychotherapy. New York, Guilford Press, 2004Google Scholar

45. Lambert MJ, Ogles BM: The efficacy and effectiveness of psychotherapy, in Bergin and Garfield’s Handbook of Psychotherapy and Behavior Change, 5th ed. Edited by Lambert MJ. New York, Wiley & Sons, 2004Google Scholar