A Depressed Adolescent at High Risk of Suicidal Behavior

A 15-year-old white male was brought to the hospital emergency department after an intentional ingestion of about 20 tablets of acetaminophen in a suicide attempt. His mother had found him lying in his bed listening to loud music, an empty pill bottle on the floor next to him. Earlier the boy had come home from a baseball game visibly upset and reported that kids from the team had blamed him for losing the game. The patient lived with his parents and a younger sister. For more than a year, he had being struggling with school performance. He had been an A student throughout middle school but had not adjusted well to high school, academically or socially. His grades were now mainly C’s, and he had been failing some classes. Baseball was important to him, but he had difficulty concentrating, and his performance had deteriorated. He had seen a psychologist a few times during the past year because of his school difficulties and was found to be anxious. As a young child, he had severe separation anxiety. His anxiety symptoms had improved, but he continued to have excessive anxiety in social situations, and he tended to isolate himself from others. He was not sexually active, had not tried street drugs, and had not had any problems with the law. However, in the past year, he had used alcohol. In the past 2 months, he was less engaged with peers, easily upset, and irritated by minor stressors. He had shown bouts of anger but had never verbalized suicidal intentions. His relationship with his father, who was demanding and critical, was tense. A cousin to whom he was particularly close had recently died in a car accident. His mother had suffered from dysthymia and insomnia for years. As a young man, his father had social phobia and abused alcohol. A paternal uncle who had been dependent on alcohol died of liver failure. In the emergency department, the patient received gastric lavage. His acetaminophen plasma level was 106 mg/ml about 4 hours after the overdose. He was hospitalized in the medical ward and later was transferred to the psychiatric unit. He met diagnostic criteria for major depressive disorder of moderate to severe degree, as indicated by a total score of 62 on the Children’s Depression Rating Scale—Revised (1) . He had clinically significant suicidal ideation, as indicated by a score of 37 on the Suicidal Ideation Questionnaire for youths (2) . He had been depressed and functionally impaired for at least 1 year. He also met criteria for generalized anxiety disorder and social phobia. There was no history of mania. The patient reported that when he overdosed, he was upset and did not really think about the consequences of what he was doing, but he admitted that, at that moment, he wanted to die because he was tired of being a failure. He had not planned the act, and he took the acetaminophen from the medicine cabinet at home. He described his act as “silly” and said that he regretted having “lost control.” Asked if he really believed he would have died of the overdose, he replied that he had not given any thought to it. What are some of the main risk factors for suicide in adolescents? What are the primary aims of treatment in suicidal youths? How would this patient best be treated?

Suicidal Behavior in Adolescence

A suicide attempt is defined as a potentially self-injurious behavior associated with expressed or implied intent to die (3 , 4) . In the 2005 national Youth Risk Behavior Survey, 8.4% of high school students reported having attempted suicide in the previous 12 months, with 2.3% reporting that medical treatment was required as a result of their attempt (5) . Suicidal ideation was more common, with about 17% of high school youths reporting ideation during the preceding 12 months. The frequency of suicidal ideation increases with the presence of risk behaviors, such as alcohol use and engaging in physical fights (6) .

Although suicide is the third leading cause of death for 15- to 19-year-olds (following unintentional injuries and homicide), adolescent suicide is rare. Girls are more likely to attempt suicide, and boys are more likely to die by suicide. In 2004, 1,700 adolescents (1,345 boys) 15–19 years old died by suicide in the United States, which corresponds to a rate of 8.20 per 100,000 (12.65/100,000 for males, and 13.57/100,000 for white males) (7) .

Having attempted suicide substantially increases the risk of further attempts and of suicide death. The reattempt rate is estimated to be as high as 30% over a 1-year period and is highest during the first few months following the attempt (8 , 9) . Most suicide attempters, however, will not die of suicide, and most youths who die of suicide have not previously attempted suicide. Despite a relatively low predictive value, suicide attempt remains the most significant predictor of future psychopathology and suicidal behavior (4) .

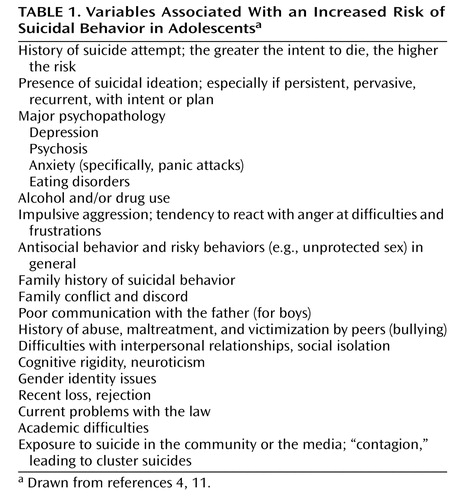

Another major risk factor for suicidal behavior is the presence of severe psychopathology. The large majority of suicide decedents and attempters suffer from a psychiatric disorder, typically depression, at the time of the event (4 , 10) . The combination of depression and a tendency to react with impulsive aggression to stress and frustration is often seen in cases of suicidal behavior. Alcohol and drug abuse contribute substantially to the risk by further increasing impulsivity. Psychosis, conduct disorder, eating disorders, and anxiety disorders also increase the risk of suicidal behavior. Other risk factors have been identified ( Table 1 ), as have some protective factors, such as an intact family, a good parent-child connection, a sense of integration with one’s peer group and community, and cultural/religious values (11) .

Although the statistical association between the variables listed in Table 1 and suicide risk is well documented, the predictive power of each risk factor in isolation is low. Risk factors tend to be intercorrelated, however, and the presence of multiple risk factors increases the risk. Thus, even though suicidal behavior cannot be predicted with clinically useful precision, patients at high risk can be identified, which is a necessary step toward developing treatment and preventive interventions (11 , 12) .

Assessment of Suicide Risk in Adolescents

A comprehensive psychiatric evaluation, with in-depth assessment of suicidal ideation, past suicidal behavior, and risk and protective factors, is essential. Suicidal ideation can range along a continuum of severity from infrequent thoughts of death, of low intensity and short duration, without plans, and with good self-control, to the development of specific plans without intent, to frequent, intense, and enduring suicidal ideation with specific plans and intent and with access to lethal methods. Standardized measures can be used to assess suicidal tendency along anchored items. For example, the Suicidal Ideation Questionnaire adapted for adolescents (2) is 15-item self-administered instrument. A total score of 31 or more is considered a “flag” for elevated suicidal risk. The Scale for Suicide Ideation, developed for adults, is applicable to adolescents (13) . Also, depression rating scales include items relevant to suicidal ideation and behavior (1) .

The stronger the intent to die in prior attempts, the higher the risk of future suicidal episodes. Intent can be explicitly expressed (e.g., “I wanted to die”) or inferred from behavior (e.g., presence of planning, lethality of the method, patient’s belief in the lethality of the act, precautions to prevent discovery and rescue). A detailed reconstruction of the chain of events leading to the attempt can help the clinician understand the dynamics of the act and develop an individualized rescue plan to prevent future suicidal behavior.

Treatment

Treatment presents multiple challenges. First, because different factors can increase the risk of suicide, treatment needs to be multifactorial and highly individualized. Second, the evidence-based scientific literature available to guide treatment is extremely limited, because suicidal youths have been systematically excluded from controlled clinical trials. Finally, treatment adherence can be problematic because many patients fail to follow up on referral recommendations or drop out of treatment soon after the acute crisis, often because of mental health service barriers and/or psychosocial issues in the family (14) .

In this context, treatment aims to decrease risk by acting on specific malleable risk factors (see Table 1 ). Thus, the main approach consists of vigorously treating any major psychopathology, having the patient develop skills for dealing with stress and frustration, improving the patient’s interpersonal relationships within the family and with peers, and restricting the patient’s access to potentially lethal means of suicide.

Treating Psychopathology

The treatment of major depression in adolescents has been the object of considerable research. More than 30 randomized trials of cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT) or interpersonal therapy and more than a dozen randomized trials of antidepressant medications have been reported (15 – 20) . Although nearly all of these trials excluded suicidal youths, the existing data still provide useful information about the treatment of depression and are relevant to depressed suicidal youths. Persistence of depression in past suicide attempters is known to be associated with reattempt. It is therefore reasonable to expect that successful treatment of depression will decrease the risk of suicide, although this has not yet been proven by controlled studies.

Both CBT and pharmacotherapy with fluoxetine are effective treatments for adolescent depression (15 , 16) . The Treatment for Adolescents With Depression Study (TADS) compared the effects of monotherapy with CBT or fluoxetine and their combination in outpatients with moderate to severe major depression (21) . Fluoxetine was more effective than CBT in improving depressive symptoms, and the combination treatment was more effective and more rapid than monotherapy in improving symptoms and achieving remission and functional recovery (22 , 23) . In TADS, 29% of participants were at high risk of suicide, as indicated by a score of 31 or more on the Suicidal Ideation Questionnaire for youths at study entry. Scores declined during treatment, and more so with combined treatment than with monotherapy. However, in a recent controlled trial of fluoxetine monotherapy and combination treatment with fluoxetine and CBT, which included depressed suicidal youths, no advantage was seen in adding CBT to medication (24) .

Antidepressants have been found to increase the risk of suicidal ideation or attempt (suicidality), although not of suicide, in youths (17) . The mechanism of this effect is unknown, but it is hypothesized that increased serotonergic transmission induces behavioral activation in some individuals, causing irritability, agitation, and impulsiveness (25) . In 2004, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) required that a black box warning, the agency’s highest level of warning, be added to the product labeling of antidepressants alerting prescribers and consumers to the increased risk of suicidality in children and adolescents during antidepressant treatment. This warning was revised in 2007 to indicate that an increased risk of suicidality was similarly observed in young adults up to 24 years of age, while no increase was detected beyond age 24 and a reduced risk was observed for patients age 65 or older (26) . There is debate about whether the decreased use of antidepressants consequent to the warning may have contributed to the observed increase in youth suicide rates in the United States and other countries (27 , 28) . The fact remains that depression and other serious mental illnesses are the most important causes of suicidal behavior, and they should be vigorously treated.

Across the 36 weeks of TADS, fluoxetine monotherapy was associated with a higher incidence of suicidality (14.7%) than CBT (6.3%) or combined treatment (8.4%) (29) . Thus, adding CBT to fluoxetine seems to attenuate the risk of suicidality during medication treatment while enhancing antidepressant effects. It is possible that CBT provides skills for managing conflict and stressful psychosocial events, as well as opportunities to discuss and identify more appropriate reactions to stress than suicidal behavior. CBT has been adapted to specifically address suicidality, and controlled clinical trials with suicidal adults have shown these adaptations to be effective in preventing suicide attempts (30 , 31) . Research is under way to develop similar approaches for adolescents.

Developing an Emergency Plan

An important tool for successful management of the suicidal adolescent is an individualized emergency plan to diffuse tension in case of stressful events and thus interrupt the chain of events leading to suicidal behavior (32) . This is not the traditional patient-clinician “contract,” which is of questionable efficacy. Rather, it is a collaboratively developed plan that builds on a detailed analysis of the specific circumstances and emotional reactions leading to suicidal behavior or to a past attempt, aiming to prevent tension from building to uncontrollable levels and providing alternative, nondestructive means of dealing with anger, frustration, or loss.

The clinician should discuss with the family options for reducing the availability of suicide methods. For example, prescription and over-the-counter medications in the household should be secured somewhere other than the bathroom medicine cabinet, and firearms should be locked up or removed from the home (4) .

Improving Family Communication

An important component of treating adolescents who have an elevated risk of suicide is family involvement. After a suicide attempt, parents are likely to be shocked, scared, and experiencing feelings of guilt and anger. Improving communication within the family is one of the tasks of psychotherapy.

Before starting treatment, parents need to know the available treatment options and the risks and benefits of each. When considering antidepressant medications, potential benefits and risks of antidepressants should be discussed in light of the needs of the individual patient. Parental supervision and close communication with the clinician are essential in order to monitor treatment effects, changes in depressive symptoms, and the emergence of any adverse effects.

Clinical Monitoring

Suicidal adolescents should have close clinical monitoring during antidepressant treatment. As noted, the risk of a reattempt is highest in the first few months after a suicide attempt (4) . Ensuring a safe transition from inpatient to outpatient setting is especially critical. Starting antidepressant medication treatment can be associated with symptoms of behavioral activation that may increase the risk of suicidal behavior. The medication dosage needs to be adjusted on the basis of clinical response and adverse effects. Emergency plans may need to be updated to remain relevant and useful.

After conducting a meta-analysis of pediatric clinical trials of antidepressants in 2004 (17) , the FDA specifically recommended a monitoring schedule for youths treated with antidepressants that included weekly face-to-face visits for the first 4 weeks and visits every other week for the following 4 weeks. The value of such a rigid approach is unproven, however, and in any case community clinicians seem not to have implemented it (33 , 34) . In 2007, the FDA dropped these monitoring recommendations from the black box warning and the medication guide, instead indicating that patients should be “monitored appropriately” and retaining a statement in the label warning indicating that patients should be “observed closely for clinical worsening, suicidality, and unusual changes in behavior, especially during the initial few months of a course of drug therapy, or at times of dose changes, either increases or decreases” (26 , 35) .

Because treatment adherence can be poor, it is important to get a clear commitment from patient and family to follow a well-defined treatment plan. For hospitalized adolescents, clear plans for outpatient treatment should be in place before the patient is discharged. Given that suicide risk is highest in the postdischarge period, missed appointments should be pursued vigorously by phone calls or mail. When multiple clinicians are involved in delivering the treatment, good communication and coordination are critical, particularly between the prescribing physician and the psychotherapist.

Summary and Treatment Directions

The current clinical approach to treating depressed suicidal adolescents relies, by necessity, on an integration of evidence-based information from controlled clinical trials conducted with depressed, nonsuicidal youths and logical inferences from our understanding of suicide risk factors. Treatment is focused on the patient’s major psychopathologies, on having the patient develop effective skills for dealing with stress and frustration, and on improving the patient’s interpersonal relations with family members and with peers. In addition, access to common means of suicide, such as medications and firearms, should be reduced.

The adolescent in the vignette attempted suicide in the context of a mood disturbance and is at risk for future suicidal acts. He suffers from severe major depression, which is superimposed on longer lasting problems with anxiety. His family history is positive for mood, anxiety, and alcohol-related disorders. The patient’s social isolation and inability to use alternative, nondestructive ways of expressing his anger, together with easy access to over-the-counter medications in the home, facilitated and led to the actual attempt. Other risk factors include academic difficulties, lack of integration within a peer group, recent loss of a relative, and experimenting with alcohol. Male gender further increases the concern about suicidal risk. Protective factors include an intact family and parental supervision.

The acute precipitant of the attempt was the frustration of losing a baseball game and being criticized by his peers. Although suicidal intent was present, the lack of planning, the choice of a method (i.e., overdosing) usually of low lethality, and an uncertain belief about the outcome of the attempt do not suggest a clear determination to die. Moreover, while the patient had not brought his suicidal act immediately to the attention of others, he had not tried to conceal it. Acetaminophen overdose, however, can have serious consequences as a result of liver toxicity. Even unplanned suicidal acts with uncertain intent can be fatal.

Given the severity of the patient’s depression, a combination of fluoxetine and CBT would offer the best chances of remission of depression and anxiety and decreasing suicidal ideation. To minimize the risk of drug-induced behavioral activation, fluoxetine could be started at the low dose of 10 mg/day, then raised to 20 mg/day within a week if there are no adverse effects and adjusted clinically thereafter. The average dose at 12 weeks in TADS was about 30 mg/day (21) . One of the tasks of CBT is to develop and rehearse an individualized emergency plan that includes concrete steps to take in case of stressful events and circumstances. CBT would be started concomitantly with pharmacotherapy and delivered in weekly sessions for at least 3 months, then less intensively, depending on clinical response (20 , 21 , 26) .

1. Poznanski EO, Mokros HB: Manual for the Children’s Depression Rating Scale—Revised. Los Angeles, Western Psychological Services, 1995Google Scholar

2. Reynolds WM: Suicidal Ideation Questionnaire: Professional Manual. Lutz, Fla, Psychological Assessment Resources, Inc, 1991Google Scholar

3. Posner K, Oquendo MA, Gould M, Stanley B, Davies M: Columbia Classification Algorithm of Suicide Assessment (C-CASA): classification of suicidal events in the FDA’s pediatric suicidal risk analysis of antidepressants. Am J Psychiatry 2007; 164:1035–1043Google Scholar

4. Bridge JA, Goldstein TR, Brent DA: Adolescent suicide and suicidal behavior. J Child Psychol Psychiatry 2006; 47:372–394Google Scholar

5. Eaton DK, Kann L, Kinchen S, Ross J, Hawkins J, Harris WA, Lowry R, McManus T, Chyen D, Shanklin S, Lim C, Grunbaum JA, Wechsler H: Youth Risk Behavior Surveillance: United States, 2005. J Sch Health 2006; 76:353–372Google Scholar

6. Swahn MH, Bossarte RM: Gender, early alcohol use, and suicide ideation and attempts: findings from the 2005 Youth Risk Behavior Survey. J Adolesc Health 2007; 41:175–181Google Scholar

7. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention: 2004 United States Suicide Injury Deaths and Rates. Atlanta, National Center for Injury Prevention and Control, 2007 (http://webappa.cdc.gov/sasweb/ncipc/mortrate10_sy.html)Google Scholar

8. Brent DA, Kolko DJ, Wartella ME, Boylan MB, Moritz G, Baugher M, Zelenak JP: Adolescent psychiatric inpatients’ risk of suicide attempt at 6-month follow-up. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 1993; 32:95–105Google Scholar

9. Goldston DB, Daniel SS, Reboussin BA, Reboussin DM, Kelley AE, Frazier PH: Psychiatric diagnoses of previous suicide attempters, first-time attempters, and repeat attempters on an adolescent inpatient psychiatric unit. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 1998; 37:924–932Google Scholar

10. Shaffer D, Gould MS, Fisher P, Trautman P, Moreau D, Kleinman M, Flory M: Psychiatric diagnosis in child and adolescent suicide. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1996; 53:339–348Google Scholar

11. Gould MS, Greenberg T, Velting DM, Shaffer D: Youth suicide risk and preventive interventions: a review of the past 10 years. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 2003; 42:386–405Google Scholar

12. Ashworth J: Practice Principles: A Guide for Mental Health Clinicians Working With Suicidal Children and Youth. Vancouver, Ministry of Children and Family Development, British Columbia, 2001. http://www.mcf.gov.bc.ca/mental_health/pdf/suicid_prev_manual.pdfGoogle Scholar

13. Beck AT, Kovacs M, Weissman M: Assessment of suicidal intention: the Scale for Suicide Ideation. J Consult Clin Psychol 1979; 47:343–352Google Scholar

14. Spirito A, Boergers J, Donaldson D, Bishop D, Lewander W: An intervention trial to improve adherence to community treatment by adolescents after a suicide attempt. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 2002; 41:435–442Google Scholar

15. Weisz JR, McCarthy CA, Valeri SM: Effects of psychotherapy for depression in children and adolescents: a meta-analysis. Psychol Bull 2006; 132:132–149Google Scholar

16. Bridge JA, Iyengar S, Salary CB, Barbe RP, Birmaher B, Pincus HA, Ren L, Brent DA: Clinical response and risk for reported suicidal ideation and suicide attempts in pediatric antidepressant treatment: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. JAMA 2007; 297:1683–1696Google Scholar

17. Hammad TA, Laughren T, Racoosin J: Suicidality in pediatric patients treated with antidepressant drugs. Arch Gen Psychiatry 2006; 63:332–339Google Scholar

18. Mufson L, Dorta KP, Wickramaratne P, Nomura Y, Olfson M, Weissman MM: A randomized effectiveness trial of interpersonal psychotherapy for depressed adolescents. Arch Gen Psychiatry 2004; 61:577–584Google Scholar

19. Brent D, Poling K: Cognitive Therapy Treatment Manual for Depressed and Suicidal Youth. Pittsburgh, Star Center, 1997Google Scholar

20. Curry JF, Wells KC: Striving for effectiveness in the treatment of adolescent depression: cognitive behavior therapy for multisite community intervention. Cogn Behav Pract 2005; 12:177–185Google Scholar

21. The TADS Team: Fluoxetine, cognitive behavior therapy, and their combination for adolescents with depression. JAMA 2004; 292:807–820Google Scholar

22. Kennard B, Silva S, Vitiello B, Curry J, Kratochvil C, Simons A, Hughes J, Feeny N, Weller E, Sweeney M, Reinecke M, Pathak S, Ginsburg G, Emslie G, March J; TADS Team: Remission and residual symptoms after short-term treatment in the Treatment of Adolescents with Depression Study (TADS). J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 2006; 45:1404–1411Google Scholar

23. Vitiello B, Rohde P, Silva S, Wells K, Casat C, Waslick B, Simons A, Reinecke M, Weller E, Kratochvil C, Walkup J, Pathak S, Robins M, March J; TADS Team: Functioning and quality of life in the Treatment for Adolescents with Depression Study (TADS). J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 2006; 45:1419–1426Google Scholar

24. Goodyer I, Dubicka B, Wilkinson P, Kelvin R, Roberts C, Byford S, Breen S, Ford C, Barrett B, Leech A, Rothwell J, White L, Harrington R: Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) and routine specialist care with and without cognitive behavior therapy in adolescents with major depression: randomized controlled trial. BMJ 2007; 335:142–149Google Scholar

25. Goodman WK, Murphy TK, Storch EA: Risk of adverse behavioral effects with pediatric use of antidepressants. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2007; 191:87–96Google Scholar

26. US Food and Drug Administration: Antidepressant Use in Children, Adolescents, and Adults: Revisions to Product Labeling. http://www.fda.gov/cder/drug/antidepressants/antidepressants_label_change_2007.pdfGoogle Scholar

27. Libby AM, Brent DA, Morrato EH, Orton HD, Allen R, Valuck RJ: Decline in treatment of pediatric depression after FDA advisory on risk of suicidality with SSRIs. Am J Psychiatry 2007; 164:884–891Google Scholar

28. Gibbons RD, Brown CH, Hur K, Marcus SM, Bhaumik DK, Erkens JA, Herings RMC, Mann JJ: Early evidence on the effects of regulators’ suicidality warnings on SSRI prescriptions and suicide in children and adolescents. Am J Psychiatry 2007; 164:1356–1363Google Scholar

29. The TADS Team: The Treatment for Adolescents With Depression Study (TADS): long-term effectiveness and safety outcomes. Arch Gen Psychiatry 2007; 64:1132–1144Google Scholar

30. Brown GK, Ten Have T, Henriques GR, Xie SX, Hollander JE, Beck AT: Cognitive therapy for the prevention of suicide attempts: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA 2005; 294:563–570Google Scholar

31. Linehan MM, Comtois KA, Murray AM, Brown MZ, Gallop RJ, Heard HL, Korslund KE, Tutek DA, Reynolds SK, Lindenboim N: Two-year randomized controlled trial and follow-up of dialectical behavior therapy versus therapy by experts for suicidal behaviors and borderline personality disorder. Arch Gen Psychiatry 2006; 63:757–766Google Scholar

32. Brunstein Klomek A, Stanley B: Psychosocial treatment of depression and suicidality in adolescents. CNS Spectr 2007; 12:135–144Google Scholar

33. Morrato EH, Libby AM, Orton HD, deGruy FV III, Brent DA, Allen R, Valuck RJ: Frequency of provider contact after FDA advisory on suicidal risk of pediatric suicidality with SSRIs. Am J Psychiatry 2008; 165:42–50Google Scholar

34. Bhatia S, Rezac AJ, Vitiello B, Sitorius MA, Buehler BA, Kratochvil CJ: Antidepressant prescribing practices for the treatment of children and adolescents. J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacology (in press)Google Scholar

35. US Food and Drug Administration: Revision to Medication Guide: Antidepressant Medicines, Depression and Other Serious Mental Illnesses, and Suicidal Thoughts or Actions. Revised May 2, 2007. http://www.fda.gov/cder/drug/antidepressants/antidepressants_MG_2007.pdfGoogle Scholar