The Revised Warning for Antidepressants and Suicidality: Unveiling the Black Box of Statistical Analyses

The U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) meeting of the Psychopharmacologic Drugs Advisory Committee (PDAC) on December 13, 2006 considered the risk of suicidality among adults who take antidepressants. This meeting came in the wake of two PDAC meetings in 2004 that resulted in a black box warning for suicidality in pediatric use of antidepressants (1) . Based on the evidence that was presented from a large body of randomized controlled clinical trials of antidepressants, the committee voted 6 to 2 in favor of extending the black box warning to include young adults (2) . Each of the six affirmative votes was accompanied by an explicit caveat that the black box warning about suicidality must include a caution about the perils of untreated depression (3) . I, the biostatistician on that PDAC, cast one of those six affirmative votes, and here I attempt to shed light on the reasoning behind my vote.

The all-day hearing included 3 hours of testimony from the public, which was dominated by heart-wrenching descriptions of tragedy. The majority of those presentations described a deceased loved one who had taken an antidepressant shortly before suicide, yet they seldom mentioned the psychopathology that served as the rationale for a physician to prescribe the antidepressant. One sequence of slides shadowed the next with photographs of a once blissful family, a productive loved one, followed by flowers and a casket. There was grief-stricken expression of animosity toward the FDA and, at times, toward the PDAC members, and a demand that all antidepressants be pulled from the shelves. This series of several dozen vignettes, limited by protocol to 3 minutes each, carried weight that was vastly disproportionate to that of the empirical evidence from hundreds of randomized controlled clinical trials.

This issue is clearly emotionally charged, and the topic is germane to the health of millions of Americans. IMS Health reported that in 2005 over 180,000,000 antidepressant prescriptions were filled in the United States (4) . However, my final opinion was not swayed by the individual testimonials that I heard that day. Rather, I based my vote on an empirically based review of the evidence that was presented to the advisory committee, prior to the public presentations. The results of two independent meta-analyses were presented that primarily focused on data from 77,382 participants in 295 randomized controlled clinical trials of antidepressants for psychiatric indications (5) .

Safety analyses of rare events, suicidality in this case, require broad medication exposure, and the magnitude of the data analyzed was unprecedented in psychopharmacology. Moreover, the convergence of results from alternative data analytic strategies was convincing. There was minimal discrepancy among the primary results of two meta-analyses, conducted independently by two groups at the FDA, and the extensive sensitivity analyses. Importantly, the pattern of results across age groups supported the possibility of a true phenomenon.

One set of analyses was conducted by Mark Levenson, Ph.D., and Chris Holland, M.S., of the Biometrics Division of the FDA; the other by Marc B. Stone, M.D., and M. Lisa Jones, M.D., of the FDA Safety Group. In each case, the primary analyses involved trial-level data, and the primary outcome was suicidality, defined as suicidal ideation, preparatory acts, attempts, or completion. The primary hypothesis centered on differences in rates of suicidality between investigational and placebo arms. The primary analysis conducted by the safety group involved fixed-effects models, whereas the primary analysis conducted by the biometrics group involved stratified estimation of odds ratios using a so-called exact method. This latter approach allows for rates of suicidality to vary across trials, yet at the same time, does not assume a large number of events per trial or a large number of subjects per trial (5) .

Initial descriptive analyses showed no difference in suicidality rates across cells: 0.62% (investigational: 248/39,729) versus 0.72% (placebo: 196/27,164), and the inferential test concurred (odds ratio=0.84; 95% confidence interval [CI]=0.69–1.02). The placebo suicidality estimate provided the background rate of suicidality in major depressive disorder over the length of a randomized controlled clinical trial, a critically important benchmark for comparison with investigational agents. If analyses had stopped here, there would have been no change in the black box warning.

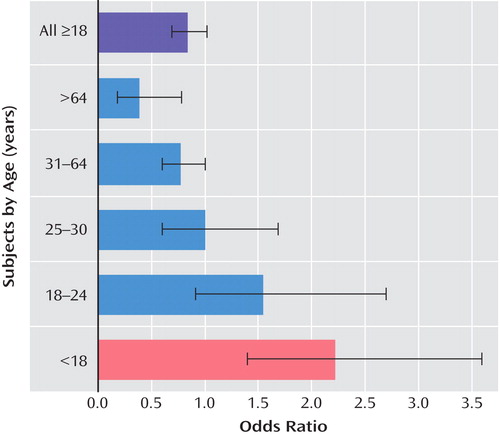

Given the 2004 findings from the pediatric trials, however, separate analyses to detect differential risk across the age groups were indicated. These age-stratified analyses were revealing. The trend across ages showed that antidepressants were significantly protective for ages 65 and higher in that the risk of suicidality was reduced substantially, by 61% for those randomly assigned to antidepressants relative to placebo (odds ratio=0.39; 95% CI=0.18–0.78; investigational [N=3,227] versus placebo [N=2,397]). There were nonsignificant effects for all other age groups, albeit higher risk in the younger age group: ages 31–64 (odds ratio=0.77; 95% CI=0.60–1.00; N=27,086 versus N=18,354), ages 25–30 (odds ratio=1.00; 95% CI=0.60–1.69; N=5,558 versus N=3,772), and ages 18–24 (odds ratio=1.55; 95% CI=0.91–2.70; N=3,810 versus N=2,604). Finally, these results were overlaid on the pediatric results, which were initially presented in 2004 by Tarek Hammad, M.D., Ph.D. of the FDA (6) . This, the most convincing graphic ( Figure 1 ), portrays a pattern of increasing benefit and decreasing risk across the age span. It is difficult to ignore the trend, particularly for the young adults. The results did not provide definitive evidence of risk, yet they failed to demonstrate an absolute absence of risk.

a Data are based on results from the FDA (2006) (5). Odds ratios >1.0 indicate that the risk of suicidality while receiving antidepressants is elevated relative to placebo; odds ratios <1.0 indicate a protective effect of antidepressants.

Extensive sensitivity analyses compared the primary results with those of analyses that made alternative assumptions about the underlying form of the data (5) . For instance, a Mantel-Haenszel method for risk differences allows the inclusion of trials with zero events (121 of 295 trials [41%]) that were excluded from the primary analyses. This approach provided a solution to the mathematically intractable nature of a ratio with a zero in the denominator. In addition, a fixed-effects logistic regression analysis was used to examine subject-level data, as opposed to the summary trial-level data. Yet another approach included both fixed and random effects and, in doing so, allowed the odds ratios to vary across trials. Additional analyses examined the sensitivity of results to other data analytic assumptions, yet apparently none were age-stratified. In sum, the results were similar across a range of analytic procedures.

Elsewhere, I have argued that there is not an ideal dataset to study this phenomenon (7) . These trials were not universally designed to detect suicidality, and the methods used for the analyses just described are vulnerable to criticism. First, the information on suicidality did not come from a prospective, systematic collection of data on suicidality, but instead was strictly obtained through the spontaneous adverse event reports. Second, efficacy was for the most part ignored, and therefore even the most informal risk-benefit analysis could not be conducted. This omission is important because the analysis of suicidality is not the same as the analysis of death rates from suicide. It is possible that the efficacy of the drugs in the treatment of depression may have positive effects in preventing suicide, even if they also increase suicidal thoughts. Finally, attrition was not accounted for in the extensive analyses, even though about 30% of participants tend to drop out of randomized controlled clinical trials for major depressive disorder, and this can introduce bias in the analyses of safety and efficacy (8) .

In conclusion, each advisory committee member plays a small but critical role as a guardian of the public health. That responsibility demands a level of empiricism that outweighs the intense social pressure from proponents and critics of the warning. My vote to extend the black box warning to young adults was based on concern that risk of suicidality could not be ruled out and, given the widespread antidepressant use, even a small risk must not be ignored. Caution is indicated. The black box warning is not meant to discourage the prescription of antidepressants. In fact, the warning refers to the hazard of untreated depression. Instead, it is meant to promote monitoring of patients who commence antidepressants.

1. U.S. Food and Drug Administration: Labeling Change Request Letter for Antidepressant Medications. Rockville, Md, FDA, 2004. http://www.fda.gov/cder/drug/antidepressants/SSRIlabelChange.htm (accessed July 2007)Google Scholar

2. U.S. Food and Drug Administration: Revisions to Product Labeling. Rockville, Md, FDA, 2007. http://www.fda.gov/cder/drug/antidepressants/default.htm (accessed 2007)Google Scholar

3. U.S. Food and Drug Administration: Psychopharmacologic Drugs Advisory Committee Meeting (transcript), Rockville, Md, FDA, 2006. http://www.fda.gov/ohrms/dockets/ac/cder06.html#PsychopharmacologicGoogle Scholar

4. IMS Health: IMS National Prescription Audit Plus, February 2006Google Scholar

5. U.S. Food and Drug Administration: Briefing Document for Psychopharmacologic Drugs Advisory Committee, December 13, 2006, http://www.fda.gov/ohrms/dockets/ac/06/briefing/2006–4272b1–01-FDA.pdf (accessed 2007)Google Scholar

6. Hammad T: Results of the analysis of suicidality in pediatric trials of newer antidepressants, in the Proceedings of the Psychopharmacologic Drugs Advisory Committee with the Pediatric Subcommittee of the Anti-Infective Drugs Advisory Committee Meeting. Rockville, Md, FDA Center for Drug Evaluation and Research, 2004. http://www.fda.gov/ohrms/dockets/ac/04/slides/2004–4065s1.htm (accessed July 2007)Google Scholar

7. Leon AC: The revised black box for antidepressants sets a public health experiment in motion. J Clin Psych 2007; 68:1139–1141Google Scholar

8. Leon AC, Mallinckrodt CH, Chuang-Stein C, Archibald DG, Archer GE, Chartier K: Attrition in randomized controlled clinical trials: methodological issues in psychopharmacology. Biol Psychiatry 2006; 59:1001–1005Google Scholar