Affective Disorders and Cognitive Failures: A Comparison of Seasonal and Nonseasonal Depression

Abstract

Seasonal depression shares certain common symptoms with nonseasonal depression; however, the two disorders have never been examined in a single study, to the authors’ knowledge. The goal of this research was to examine the potential similarities in cognitive impairments in seasonal affective disorder and major depressive disorder in college students in the Midwest. Identification of affective disorders was based on participants’ self-reported behavior and affect on the Beck Depression Inventory and the Seasonal Pattern Assessment Questionnaire. A group of 93 participants was assessed for major depressive disorder and seasonal affective disorder in late autumn and completed the Cognitive Failures Questionnaire for reported difficulties in everyday activities that correspond to problems with perception, attention, and memory retrieval. The results indicated that seasonal affective disorder was highly prevalent (28.0%), substantially more so than major depressive disorder (8.6%). Similar to previous research on major depressive disorder, gender differences were also evident among participants with seasonal affective disorder, with more women qualifying than men. Both affective disorders were associated with higher reports of cognitive failures in comparison to participants with no depressive symptoms. These results reveal that individuals with seasonal affective disorder showed cognitive impairments similar to those with nonseasonal depression.

In 1984, Rosenthal and colleagues (1) coined the phrase “seasonal affective disorder” to describe this subcategory of mood disorder in which people’s major depressive episodes have clear seasonal patterns. By far the most common is winter depression, which is marked by atypical vegetative symptoms of depression, including hypersomnia, increased appetite, carbohydrate craving, hyperphagia, lack of interest in social activities, impaired concentration, energy loss, and weight gain. People living in northern latitudes are more susceptible to seasonal affective disorder, as are younger people and women. Seasonal affective disorder is believed to affect at least 5% of the general population of the United States, and of that number, between 60% and 90% are women (DSM-IV-TR).

Seasonal depression occurring in the winter months is thought to result from sensitivity to light deficiency, which affects the body’s circadian rhythms. When light diminishes in winter, the internal clock falls out of synchrony with the solar cycle, and this causes a circadian phase shift in body rhythms, such as core body temperature and hormone secretion, specifically, melatonin (2 , 3) .

Seasonal depression shares many attributes with major depressive disorder. The symptoms of major depressive disorder include depressed, despairing, or irritable mood; loss of interest in life; feelings of worthlessness; excessive or inappropriate guilt; low self-esteem; indecisiveness; fatigue; diminished ability to think or concentrate; and anhedonia, the inability to experience pleasure (see DSM-IV-TR). There are alterations in energy, with feelings of listlessness and lethargy and reduced motivation to the extent that most activities and movements require overwhelming effort (DSM-IV). There are also disturbances in physical functions, most notably in appetite and sleep. In major depressive disorder, disruptions of sleeping and eating can vary widely, although typical symptoms involve hypophagia, weight loss, and insomnia. In contrast, seasonal depression is marked by more universally experienced symptoms of hyperphagia, weight gain, and hypersomnia.

Cognitive Impairment and Depressive Disorders

Mentioned briefly in DSM as “a diminished ability to think or concentrate” (DSM-IV), the effects of depression on cognitive functioning are more wide-ranging and pronounced than this statement indicates. Deficits in verbal fluency (4 , 5) , visual search (6) , psychomotor speed (7) , attention (8) , and working memory (9 , 10) have been reported. Automatic processing abilities remain largely intact (6) .

Few studies have examined the cognitive impairment in seasonal affective disorder, initially finding associated deficits for individuals with seasonal affective disorder on tasks requiring an extended period of mental effort, perceptual flexibility, and abstract thinking (1) . O’Brien et al. (11) also administered a wide array of assessments for cognitive ability (i.e., spatial recognition, short-term memory, learning, and psychomotor speed) to 11 patients with seasonal affective disorder and 10 comparison subjects who were matched for age, IQ, and education. The tests were administered once in the winter and again in the summer after remission of symptoms and clinical recovery. Impairments in pattern recognition, visual short-term memory, and visual learning that were observed in the winter (in relation to comparison subjects) improved after clinical recovery in the summer. A study by Michalon et al. (12) administered visual and verbal assessments to 30 patients with seasonal affective disorder and 29 age- and education-matched comparison subjects before and after 2 weeks of light treatment. The most consistent deficits associated with seasonal affective disorder were on tests of visual memory and visual construction skills, both of which improved after light therapy.

Given the scarcity of research on seasonal affective disorder and cognitive deficits, the goal of the current study was to better understand the similarities between seasonal and nonseasonal depression in cognitive function. Instead of assessing highly specific cognitive processes, we chose to examine a broader category of functions that appear to be evident to the individual in real-world activities. Cognitive failures are the reported difficulties people experience in typical everyday situations (e.g., forgetting names or misinterpreting directions) that are linked to lapses in controlled processes, such as focus of attention and working memory (13) . Assessing cognitive failures includes asking individuals to rate how often certain mistakes occur, such as forgetting what you went to the store to buy, failing to notice signs, or missing appointments (14) . Although cognitive failures are not considered to be particularly dangerous in and of themselves, they are strongly related to more serious occurrences, such as car accidents, hospitalizations, and falling injuries (15) and work-related accidents (16) . The present study identified individuals who have seasonal affective disorder or who have major depressive disorder by observing self-reported responses on affective inventories (the Beck Depression Inventory and the Seasonal Pattern Assessment Questionnaire). We expected that in the Midwestern region of the United States there would be college students qualifying for seasonal and nonseasonal depression during the month of November, allowing a comparison of cognitive failures across the two types of depression, along with a nondepressed group.

Method

Participants

The group was composed of 93 student volunteers taking psychology courses at Kenyon College, a private liberal arts school in the Midwest (Ohio). Of the 93 participants, 65 (69.9%) were women, and 28 (30.1%) were men. All students were between the ages of 18 and 22 years.

Materials

The Beck Depression Inventory and its revision, the Beck Depression Inventory—II (17) , are among the most widely used and researched instruments for assessing the severity of depression. Eighteen is the cutoff score typically used to classify patients with major depressive disorder (17) , and it has been found to show a good balance of sensitivity (79%) and false positive (16%) rates (18) . Therefore, a score of 18 or above was used in this study to designate a participant as having major depressive disorder. Although the participants did not receive structured diagnostic interviews for the current study, they were given initial surveys to indicate whether they had already received diagnostic interviews, were currently in treatment, or were aware of acute stress that might indicate a need for treatment.

For the Seasonal Pattern Assessment Questionnaire (1) , the participants reported seasonal variations in mood, weight, appetite, sleep length, social activity, concentration, and energy. This assessment is also high in internal consistency (19) and test-retest reliability and has an estimated identifying efficiency of 57% (20) . It remains the most commonly used measurement in the identification of seasonal affective disorder. The Seasonal Pattern Assessment Questionnaire is scored by adding up the participant’s ratings on items assessing seasonal change in terms of alternations in the depressive symptoms and the degree to which they feel that the changes affect their lives. A total rating score of 12 or higher of a possible score of 24 on the Seasonal Pattern Assessment Questionnaire indicated a diagnosis of seasonal affective disorder in the current study.

The Cognitive Failures Questionnaire (14) is a measure of self-reported deficits in the completion of simple everyday tasks that a person should normally be capable of completing without error and includes failures in attention, memory, perception, and motor function, for example, “Do you find you forget why you went from one part of the house to the other?” “Do you bump into people when you walk?” or “Do you find you forget appointments?” Participants are asked how often they make mistakes on a 5-point Likert scale, from 0 (never) to 4 (very often). The Cognitive Failures Questionnaire is scored by adding up the ratings for 25 items, and the highest possible total is 100, with a higher score indicating a higher incidence of cognitive failures. The Cognitive Failures Questionnaire has high internal validity (alpha=0.91) and is stable over long periods of time, with a test-retest reliability rate of 0.82 (21) .

Procedure

The testing sessions occurred during the second and third weeks of November, during which the weather was cool and overcast, with an average of 52°F the week of Nov. 16–22, 2003, and an average of 50°F the week of Nov. 23–29, 2003, with 8 hours of sunlight. The Seasonal Pattern Assessment Questionnaire, the Beck Depression Inventory—II, and the Cognitive Failures Questionnaire were administered in group sessions with no more than 20 people at a time. After signing informed consent forms, the participants completed the measures at their own pace and were debriefed afterward.

Results

Group Characteristics

The participants fell into three categories of depression (none, seasonal affective disorder, and major depressive disorder) based on their scores from the mood inventories. There were 59 participants (63.4%) in the nondepressed group, 26 (28.0%) in the seasonal affective disorder group, and 8 (8.6%) in the major depressive disorder group, which provided support for our hypothesis that the mood disorders would be observable in a Midwestern college student group in late autumn. It is important to note that three of the participants in the seasonal affective disorder group had depressive symptoms to the extent of qualifying for major depressive disorder, but they were reported seasonally. Only three of the participants with qualifying seasonal affective disorder symptoms reported being diagnosed by a clinician and currently receiving treatment, whereas all but one participant who qualified for major depressive disorder based on the Beck Depression Inventory score criterion indicated participation in a current treatment program based on a previous diagnosis from a mental health care professional.

In fact, the participants with seasonal affective disorder generally reported more severe symptoms of depression. Results of independent-sample t tests indicated that scores on the depression inventory were significantly higher for those qualifying for seasonal affective disorder (mean=10.20, SD=7.75) than for those who did not (mean=6.79, SD=5.16) (t=–2.52, df=92, p<0.05).

Depressive Disorders and Cognitive Failures

As expected, scores on the cognitive failures assessment significantly correlated with total scores on both mood inventories, and the magnitude of the relationships was relatively similar for both mood measures (Beck Depression Inventory: r=0.47, p<0.01; Seasonal Pattern Assessment Questionnaire: r=0.53, p<0.01). The two mood inventories also correlated significantly with each other (r=0.36, p<0.01).

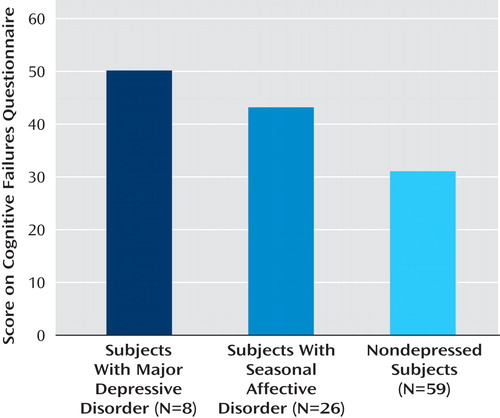

Additional evidence for the relationship between cognitive failures and affect is observable by comparing the three groups on mean score on the Cognitive Failures Questionnaire (major depressive disorder group: mean=50.17, SE=6.03; seasonal affective disorder group: mean=43.19, SE=2.25; nondepressed group: mean=31.07, SE=1.40) ( Figure 1 ). Results of a one-way analysis of variance indicated that the groups were significantly different in reported cognitive impairments on the Cognitive Failures Questionnaire (F=15.70, df=2, 92, p<0.001). Post hoc analyses (Tukey’s honestly significant difference) revealed that the nondepressed group had significantly lower Cognitive Failures Questionnaire scores than either the seasonal affective disorders group (p<0.001) or the major depressive disorder group (p<0.001), but the two depressed groups were not significantly different from one another in mean Cognitive Failures Questionnaire scores (p>0.05). These findings support the hypothesis that seasonal affective disorder and major depressive disorder are very similar in terms of cognitive impairments. Refer to Table 1 for a summary of characteristics of individuals in this study qualifying for seasonal affective disorder, along with associated cognitive failure scores.

Gender Differences

For the group of men, 85% were nondepressed, 11% qualified for seasonal affective disorder, and 4% qualified for major depressive disorder, whereas for the group of women, 49% were nondepressed, 42% qualified for seasonal affective disorder, and 9% qualified for major depressive disorder.

Gender differences were also observable in the mean scores for men and women on the mood inventories. Independent-sample t tests were used to assess gender differences in scores on the Seasonal Pattern Assessment Questionnaire and the Beck Depression Inventory—II. The difference was most significant for scores on the Seasonal Pattern Assessment Questionnaire (t=2.15, df=91, p<0.05); women reported higher scores on the Seasonal Pattern Assessment Questionnaire (mean=10.18, SD=4.38) than did men (mean=7.29, SD=4.14). Although women also had higher scores on the Beck Depression Inventory—II than did men, the difference was not statistically significant.

Discussion

The rates of occurrence of seasonal affective disorder and major depressive disorder were fairly comparable to previous rates with college samples (22 , 23) . The finding that individuals with seasonal affective disorder had higher scores on the Beck Depression Inventory—II also supports the concept that individuals with seasonal affective disorder were experiencing higher levels of depressive symptoms than the comparison subjects, which lends validity to seasonal affective disorder being a significant affective disorder.

Additionally, the findings attest to differential gender effects associated with seasonal affective disorder, such that the women had significantly higher scores on the Seasonal Pattern Assessment Questionnaire than the men did. This suggests that women are more likely to either experience or report seasonal affective disorder than men are, which is consistent with the findings of the study by Low and Feissner (23) and with the prevalence statistics listed in DSM-IV-TR.

Most notably, however, the results indicated that seasonal affective disorder has a significant impact on cognitive function, such that people with seasonal affective disorder or major depressive disorder are more likely to have a higher rate of cognitive failures on a day-to-day basis than are people without depression. Furthermore, the rate of reported cognitive failures was statistically equivalent for those with seasonal affective disorder and major depressive disorder in spite of differences in clinical symptoms. These results are consistent with the cognitive impairments associated with seasonal affective disorder found by previous researchers (1 , 11 , 12) and with the findings of many studies on cognitive impairments associated with nonseasonal depression. Several studies have illustrated that both mood disorders are prevalent among college students, and this study suggests that seasonal affective disorder is substantially the more prevalent of the two. Unfortunately, it may be the case that reported symptoms of seasonal affective disorder are less likely to be diagnosed, and hence treated, owing to the seasonal nature of symptoms. This assumption is consistent with the data presented in Table 1 , indicating that very few individuals who qualify for seasonal affective disorder are in treatment. Since attentional focus, perceptual discrimination, and memory retrieval are of utmost importance to students’ success in college, many who suffer could benefit from wider awareness and treatment.

1. Rosenthal NE, Sack DA, Gillin JC, Lewy AJ, Goodwin FK, Davenport Y, Mueller PS, Newsome DA, Wehr TA: Seasonal affective disorder: a description of the syndrome and preliminary findings with light therapy. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1984; 41:72–80Google Scholar

2. Dahl K, Avery DH, Lewy AJ, Savage MV, Brengelmann GL, Larsen LH, Vitiello MV, Prinz PN: Dim light melatonin onset and circadian temperature during a constant routine in hypersomnic winter depression. Acta Psychiatr Scand 1993; 88:60–66Google Scholar

3. Avery DH, Dahl K, Savage MV, Brengelmann GL, Larsen LH, Kenny MA: Circadian temperature and cortisol rhythms during a constant routine are phase-delayed in hypersomnic winter depression. Biol Psychiatry 1997; 41:1109–1123Google Scholar

4. Fossati P, Guillaume le B, Ergis AM, Allilaire JF: Qualitative analysis of verbal fluency in depression. Psychiatry Res 2003; 117:17–24Google Scholar

5. Videbech P, Ravnkilde B, Kristensen S, Egander A, Clemmensen K, Rasmussen NA, Gjedde A, Rosenberg R: The Danish PET/depression project: poor verbal fluency performance despite normal prefrontal activation in patients with major depression. Psychiatry Res 2003; 123:49–63Google Scholar

6. Hammar A, Lund A, Hugdahl K: Long-lasting cognitive impairment in unipolar major depression: a 6-month follow-up study. Psychiatry Res 2003; 118:189–196Google Scholar

7. Portella MJ, Marcos T, Rami L, Navarro V, Gasto C, Salermo M: Residual cognitive impairment in late-life depression after a 12-month follow-up. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry 2003; 18:571–576Google Scholar

8. Gallassi R, Morreale A, Pagni P: The relationship between depression and cognition. Arch Gerontol Geriatr Suppl 2001; 7:163–171Google Scholar

9. Lawrie SM, MacHale SM, Cavanagh JT, O’Carroll RE, Goodwin GM: The difference in patterns of motor and cognitive function in chronic fatigue syndrome and severe depressive illness. Psychol Med 2000; 30:433–442Google Scholar

10. Elderkin-Thompson V, Kumar A, Bilker WB, Dunkin JJ, Mintz J, Moberg PJ, Mesholam RI, Gur RE: Neuropsychological deficits among patients with late-onset minor and major depression. Arch Clin Neuropsychol 2003; 18:529–549Google Scholar

11. O’Brien JT, Sahakian BJ, Checkley SA: Cognitive impairments in patients with seasonal affective disorder. Br J Psychiatry 1993; 163:338–343Google Scholar

12. Michalon M, Eskes GA, Mate-Kole CC: Effects of light therapy on neuropsychological function and mood in seasonal affective disorder. J Psychiatry Neurosci 1997; 22:19–28Google Scholar

13. Austin MP, Mitchell P, Goodwin GM: Cognitive deficits in depression: possible implications for functional neuropathology. Br J Psychiatry 2001; 178:200–206Google Scholar

14. Broadbent DE, Cooper PF, FitzGerald P, Parkes KR: The Cognitive Failures Questionnaire (CFQ) and its correlates. Br J Clin Psychol 1982; 21:1–16Google Scholar

15. Larson GE, Alderton DL, Neideffer M, Underhill E: Further evidence on dimensionality and correlates of the Cognitive Failures Questionnaire. Br J Psychol 1997; 88:29–38Google Scholar

16. Wallace JC, Vodanovich SJ: Workplace safety performance: conscientiousness, cognitive failure, and their interaction. J Occup Health Psychol 2003; 8:316–327Google Scholar

17. Beck AT, Steer RA, Brown GK: Manual for the Beck Depression Inventory—II. San Antonio, Tex, Psychological Corporation, 1996Google Scholar

18. Sprinkle SD, Lurie D, Insko SL, Atkinson G, Jones GL, Logan AR, Bissada NN: Criterion validity, severity cut scores, and test-retest reliability of the Beck Depression Inventory—II in a university counseling center sample. J Couns Psychol 2002; 49:381–385Google Scholar

19. Magnusson A, Friis S, Opjordsmoen S: Internal consistency of the Seasonal Pattern Assessment Questionnaire (SPAQ). J Affect Disord 1997; 42:113–116Google Scholar

20. Raheja SK, King EA, Thompson C: The Seasonal Pattern Assessment Questionnaire for identifying seasonal affective disorders. J Affect Disord 1996; 41:193–199Google Scholar

21. Wallace JC, Kass SJ, Stanny CJ: The Cognitive Failures Questionnaire revisited: dimensions and correlates. J Gen Psychology 2002; 129:238–256Google Scholar

22. Lafay N, Manzanera C, Papet N, Marcelli D, Senon JL: Depression states during post-adolescence: results of a study in 1521 students of Poitiers University. Annales Medico Psychologiques 2003; 161:147–151Google Scholar

23. Low KG, Feissner JM: Seasonal affective disorder in college students: prevalence and latitude. J Am Coll Health 1998; 47:135–137Google Scholar