Multicenter Investigation of the Opioid Antagonist Nalmefene in the Treatment of Pathological Gambling

Abstract

OBJECTIVE: Pathological gambling is a disabling disorder experienced by approximately 1%–2% of adults and for which there are few empirically validated treatments. The authors examined the efficacy and tolerability of the opioid antagonist nalmefene in the treatment of adults with pathological gambling. METHOD: A 16-week, randomized, dose-ranging, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial was conducted at 15 outpatient treatment centers across the United States between March 2002 and April 2003. Two hundred seven persons with DSM-IV pathological gambling were randomly assigned to receive nalmefene (25 mg/day, 50 mg/day, or 100 mg/day) or placebo. Scores on the primary outcome measure (Yale-Brown Obsessive Compulsive Scale Modified for Pathological Gambling) were analyzed by using a linear mixed-effects model. RESULTS: Estimated regression coefficients showed that the 25 mg/day and 50 mg/day nalmefene groups had significantly different scores on the Yale-Brown Obsessive Compulsive Scale Modified for Pathological Gambling, compared to the placebo group. A total of 59.2% of the subjects who received 25 mg/day of nalmefene were rated as “much improved” or “very much improved” at the last evaluation, compared to 34.0% of those who received placebo. Adverse experiences included nausea, dizziness, and insomnia. CONCLUSIONS: Subjects who received nalmefene had a statistically significant reduction in severity of pathological gambling. Low-dose nalmefene (25 mg/day) appeared efficacious and was associated with few adverse events. Higher doses (50 mg/day and 100 mg/day) resulted in intolerable side effects.

Pathological gambling, characterized by persistent and recurrent maladaptive patterns of gambling behavior, is associated with impaired functioning, reduced quality of life, and high rates of bankruptcy, divorce, and incarceration (1). The past-year adult prevalence rate for pathological gambling is estimated to be 1%, similar to estimates for schizophrenia and bipolar disorder (2). Because untreated pathological gambling symptoms can impair function in multiple domains (3), empirically validated treatments for pathological gambling are needed.

Few randomized, controlled clinical trials have evaluated medication treatments for pathological gambling. Studies of serotonin reuptake inhibitors have shown mixed results, with only some studies demonstrating that the efficacy of the drug was superior to that of placebo (4). In pathological gamblers with co-occurring bipolar disorder symptoms, lithium was superior to placebo in reducing gambling and manic symptoms (5). Despite their promise, these studies have multiple limitations, including small numbers of patients and geographic homogeneity (i.e., generally performed at single sites), that may restrict the generalizability of the findings.

Given its efficacy in the treatment of alcohol and opiate dependence (6–9), the opioid receptor antagonist naltrexone was examined in the treatment of pathological gambling (10). In a double-blind, placebo-controlled, single-site study of naltrexone, 75% of naltrexone-treated subjects were either “much improved” or “very much improved” according to Clinical Global Impression ratings, compared to 24% of those receiving placebo (10). Despite the efficacy finding, the high dose of naltrexone (mean end-of-study dose was 188 mg/day) was associated with liver function test abnormalities in more than 20% of naltrexone-treated subjects, consistent with naltrexone’s dose-dependent hepatotoxicity.

Nalmefene hydrochloride, a long-acting opioid antagonist without associated liver toxicity, has demonstrated efficacy in the treatment of alcohol dependence (11). On the basis of encouraging preliminary reports of the efficacy of naltrexone in pathological gambling and nalmefene’s lack of hepatotoxicity, we conducted a large double-blind, randomized, multicenter trial of nalmefene for pathological gambling. We hypothesized that nalmefene would reduce gambling symptoms (urges/thoughts and behaviors) in subjects with pathological gambling.

Method

Subjects

Men and women age 18 years or older with a primary DSM-IV diagnosis of pathological gambling were recruited through newspaper advertisements and referrals for medication treatment. Subjects were required to meet the DSM-IV criteria for pathological gambling as assessed with the clinician-administered Structured Clinical Interview for Pathological Gambling. A minimum score of 5 on the South Oaks Gambling Screen, at least moderate urges to gamble within the week before study entry (i.e., score ≥2 on the urge component of the Gambling Symptom Assessment Scale), and gambling behavior within 2 weeks before enrollment were required. Women subjects were required to have a negative result on the beta-human chorionic gonadotropin pregnancy test and to use a medically accepted form of contraception.

Exclusion criteria included 1) current axis I disorder determined with the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV (SCID), except for nicotine dependence; 2) lifetime history of bipolar I disorder or bipolar II disorder, dementia, schizophrenia, or any psychotic disorder determined with the SCID; 3) current or recent (past 3 months) DSM-IV substance abuse or dependence; 4) treatment for pathological gambling (other than Gamblers Anonymous) within the last 6 months; 5) baseline score of >17 on either the 17-item Hamilton Depression Rating Scale (HAM-D) or the Hamilton Anxiety Rating Scale (HAM-A); 6) infrequent gambling (e.g., lottery and bingo) that did not meet the DSM-IV criteria for pathological gambling; 7) positive results on a urine drug screen (except for cannabis); 8) unstable medical condition; and 9) concomitant use of psychotropic medication.

The research was conducted at 15 outpatient psychiatric treatment centers in the United States from March 2002 through April 2003. Each treatment center’s institutional review board approved the study and the informed consent procedure. After complete description of the study, subjects provided written informed consent.

Study Design

Dose range selection was based on nalmefene’s clinical and pharmacokinetic data and on studies of naltrexone in the treatment of pathological gambling (4, 10, 11). Studies with naltrexone in pathological gambling have suggested that relatively high doses (i.e., 3–4 times the recommended therapeutic dose approved for alcohol dependence) may be needed to elicit a therapeutic response (4, 10). Thus, we selected nalmefene doses of 25 mg/day, 50 mg/day, and 100 mg/day, although findings in alcoholism studies suggested that doses above 20 mg/day or 40 mg/day may confer no additional therapeutic benefit (11).

After screening, eligible subjects were randomly assigned (in blocks of eight by using computer-generated randomization with no clinical information) to one of the following four conditions: 25 mg/day, 50 mg/day, and 100 mg/day of nalmefene or placebo. Treatment was initiated at 25 mg/day of nalmefene or the placebo equivalent during week 1. At week 2, the subjects randomly assigned to receive 50 mg/day or 100 mg/day of nalmefene began receiving the higher doses. After week 2, the subjects continued to take the doses to which they were randomly assigned. Subjects were free to withdraw from the study at any time. Any subject who was significantly nonadherent to the study procedures could be discontinued from the study. The subjects were assessed during outpatient visits at weeks 1, 2, 4, 6, 8, 10, 12, and 16 of the study.

Screening Assessments

At screening, the subjects were evaluated with the Structured Clinical Interview for Pathological Gambling, a reliable and valid diagnostic instrument that is based on the DSM-IV criteria for pathological gambling. Psychiatric comorbidity was assessed with the SCID. The subjects were assessed for medical history, and a physical examination, electrocardiogram, and routine laboratory testing were completed. The investigators rated subjects’ pathological gambling symptoms using the Yale-Brown Obsessive Compulsive Scale Modified for Pathological Gambling. The subjects reported on the severity of their pathological gambling using the South Oaks Gambling Screen and the self-rated Gambling Symptom Assessment Scale. Subjects’ psychosocial functioning was assessed with the self-report Sheehan Disability Scale. Although subjects with a lifetime alcohol use disorder were excluded, alcohol intake was assessed with the self-report Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test.

Efficacy and Safety Assessments

The primary outcome measure was the Yale-Brown Obsessive Compulsive Scale Modified for Pathological Gambling total score. Investigators who were blind to subjects’ group assignment administered the scale at every outpatient visit. The Yale-Brown Obsessive Compulsive Scale Modified for Pathological Gambling is a reliable and valid 10-item clinician-administered scale used to rate gambling symptoms within the last 7 days. The first five items of the scale constitute the gambling urge/thought subscale, which measures time occupied with urges/thoughts, interference and distress due to urges/thoughts, and resistance against and control over urges/thoughts. Items 6–10 constitute the gambling behavior subscale, which measures time spent gambling, amount of gambling, interference and distress due to gambling, and ability to resist and control gambling. Items are rated from 0 to 4, with higher scores reflecting greater severity; total scores range from 0 to 40. Each subscale was used as a secondary efficacy measure. Other secondary outcome measures were the Gambling Symptom Assessment Scale, the Clinical Global Impression (CGI) improvement scale, and the Sheehan Disability Scale.

The Gambling Symptom Assessment Scale, a reliable, valid 12-item self-rated scale, is used to assess gambling urges, thoughts, and behaviors during the previous 7 days. Each item is rated 0 to 4, with higher scores reflecting greater pathological gambling severity.

The CGI improvement scale is a reliable, valid seven-item scale that was used to evaluate change in pathological gambling symptoms since the baseline visit. The scale ranges from 1 (very much improved) to 7 (very much worse). Clinicians completed the CGI at every outpatient visit.

The Sheehan Disability Scale is a reliable, valid three-item self-report scale used to assess functioning in work, social, or leisure activities and in home and family life. Each item is rated on an 11-point Likert-type scale ranging from 0 (no impairment) to 10 (extreme impairment). The mean of the three item values was used as a secondary outcome assessment.

Safety assessments (sitting blood pressure, heart rate, adverse effects, and use of concomitant medications) were documented at each visit. Laboratory assessments, including clinical chemistry measures, hematology measures, liver function tests, and urinalysis, were performed at screening and at week 16; liver function tests were also performed at weeks 4 and 8. The 17-item HAM-D, the HAM-A, and urine pregnancy tests were completed at screening and at weeks 8 and 16. Medication adherence was monitored by pill count.

Statistical Analysis

To calculate the number of subjects needed to detect a mean difference in scores on the Yale-Brown Obsessive Compulsive Scale Modified for Pathological Gambling, we used total scores reported in a previous study (mean=14.6, SD=7.1) (12). For the current study, we assumed 30% and 60% decreases in scores for the placebo group and all nalmefene groups, respectively, by week 16, leading to mean scores of 10.2 and 5.8. Normal distribution was assumed. To detect a mean difference of 4.4 with 80% power and a 5% significance level in a two-sided test, 43 subjects per group were needed. To account for expected dropouts, we chose 50 as the number of subjects needed per group.

All subjects who were randomly assigned to study groups were included in the intent-to-treat analyses of baseline demographic characteristics and safety. In all efficacy analyses, only subjects with at least two postrandomization observations were included (to guarantee that a slope for a linear regression line could be calculated), except for the analysis of CGI improvement, where only one evaluation was required. No imputation was undertaken for missing outcome data. All tests of hypotheses were performed by using a two-sided significance level of 0.05.

The statistical model for the primary variable (Yale-Brown Obsessive Compulsive Scale Modified for Pathological Gambling total score) was a linear mixed-effects model that included terms for treatment group, time, site, treatment-by-time interaction, and treatment-by-site interaction. Each subject’s outcome profile (i) between the week-1 and week-16 visits was summarized with a linear regression line defined by a subject-specific intercept αi and slope βi. The subject-specific intercept αi was assumed to depend on the subject’s Yale-Brown Obsessive Compulsive Scale Modified for Pathological Gambling total score at baseline and on study site and treatment group, while the subject-specific slope βi was assumed to depend on the treatment group. The number of study sites in the analysis was reduced from 15 to six by pooling the data from the sites with small enrollment (N<16). The longitudinal factor of time was defined as weeks since randomization minus 1. Thus, the groupwise intercepts represent model-based mean scores at the scheduled week-1 visit (time=0), while the groupwise slopes represent the evolution of mean scores during weeks 2–16. The model seems to appropriately describe the observed biphasic shape of the response curves.

The statistical test for the null hypothesis “no treatment effect” was performed by testing simultaneously the differences in groupwise intercepts and slopes, with both being clinically meaningful. Linear contrasts were programmed for each nalmefene group versus the placebo group and for all nalmefene groups versus the placebo group. This same statistical model was applied to the Gambling Symptom Assessment Scale total score and Yale-Brown Obsessive Compulsive Scale Modified for Pathological Gambling urge/thought and behavior subscale scores.

The mean scores on the Sheehan Disability Scale had a Poisson-type distribution, with a large proportion of values close to zero. The model was therefore converted to a log-linear model to account for this distribution. Because the first postrandomization Sheehan Disability Scale score was obtained at week 4, the intercepts represent model-based mean scores at week 4.

The rates of CGI improvement were evaluated by fitting an ordinal logistic regression model in which the distributions of the last-observed CGI ratings are associated with the indicators of treatment group and gender.

Cox proportional hazards regression analysis was performed to examine time to discontinuation. Group differences in the HAM-A and the HAM-D scores were tested cross-sectionally with Kruskal-Wallis tests, as linear models were considered inappropriate because of the strongly skewed distributions. Descriptive statistics were used to evaluate changes in laboratory values, blood pressure, and heart rate.

All statistical analyses were carried out by using SAS 8.2 (13). The linear mixed-effects models, log-linear mixed-effects models, logistic regression models, and survival analysis were fitted with the procedures MIXED, NLMIXED, LOGISTIC, and PHREG, respectively (13).

Results

Subject Characteristics

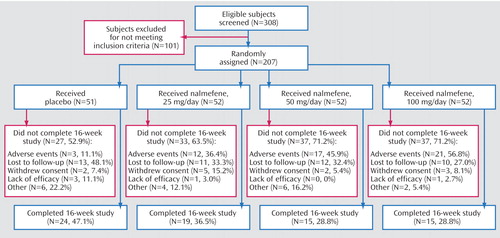

Of 308 subjects screened, 207 subjects (mean age=45.9 years, SD=11.4, range=19–72; 90 women [43.5%]) were randomly assigned to receive nalmefene in doses of 25 mg/day (N=52), 50 mg/day (N=52), or 100 mg/day (N=52) or to receive placebo (N=51). Figure 1. summarizes subject disposition throughout the study.

Demographic and clinical characteristics at baseline are presented in Table 1. Preplanned statistical tests revealed no statistically significant imbalances regarding age, gender, body mass index, employment, living status, or Yale-Brown Obsessive Compulsive Scale Modified for Pathological Gambling total scores among the treatment groups.

Premature Discontinuation

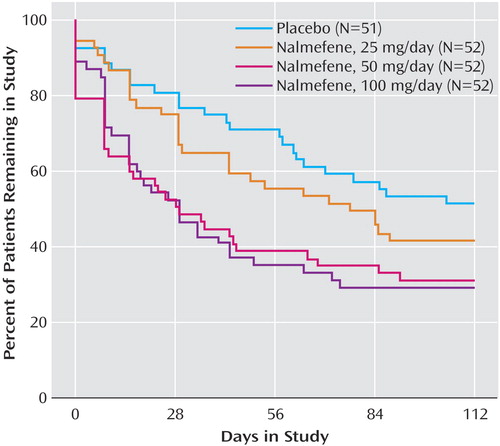

The following categories of reasons for premature discontinuation were defined in the study protocol: adverse events, lack of efficacy, loss to follow-up, subject withdrawal, or other. Premature discontinuation was common in all groups, with 66% of all randomly assigned subjects dropping out before week 16. Twenty-four (47%) of 51 subjects assigned to the placebo group and 49 (31%) of 156 subjects assigned to a nalmefene group completed the 16-week trial. The most common reasons for discontinuation in subjects taking nalmefene were adverse events (47%, N=50 of 107) and loss to follow-up (31%, N=33 of 107). Figure 2 presents data on the temporal frequency of treatment discontinuation. Cox proportional hazards regression analysis revealed significantly more and earlier discontinuations in the groups receiving 50 mg/day and 100 mg/day of nalmefene, compared to the placebo group (hazard ratio=1.98, p=0.008, and hazard ratio=2.08, p=0.004, respectively). Discontinuation in the group receiving 25 mg/day of nalmefene did not differ significantly from that in the placebo group (hazard ratio=1.30, p=0.33).

Efficacy Results

Primary outcome variable

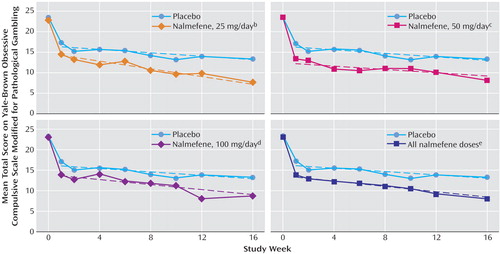

The parameter estimates from the analysis of the mean Yale-Brown Obsessive Compulsive Scale Modified for Pathological Gambling total scores are shown in Table 2 and Figure 3. Estimated regression lines demonstrated statistically significant differences among all treatment groups (F=2.80, df=6, 103, p<0.02, global test of intercepts and slopes). In pairwise tests of estimated regression coefficients, the groups receiving 25 mg/day and 50 mg/day of nalmefene had significantly different outcome scores, compared with the placebo group (p=0.007 and p<0.02, respectively), but the group receiving 100 mg/day did not (p=0.12).

Because no significant differences were found in the regression lines among the three nalmefene groups (F=1.43, df=4, 103, p=0.23), the data for the nalmefene groups were combined and were compared to the data for the placebo group. The average regression line of the nalmefene groups differed significantly from that of the placebo group (p=0.006, pairwise test of estimated regression coefficients), with a benefit of –2.86 points by week 1 and an additional weekly benefit of –0.12 point during weeks 2–16, leading to an estimated difference of –4.64 points (95% confidence interval [CI]=–7.75 to –1.53) by week 16.

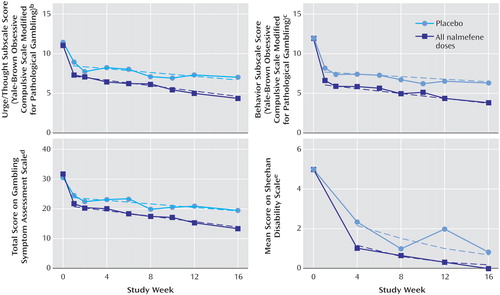

Secondary outcome measures

The results for the Yale-Brown Obsessive Compulsive Scale Modified for Pathological Gambling urge/thought and behavior subscales were consistent with the results for the total score. The difference among treatment groups for the behavior subscale was statistically significant (F=2.95, df=6, 107, p<0.02). For the urge/thought subscale, the difference among treatment groups approached significance (F=2.07, df=6, 101, p=0.06). The estimated values at week 1 and slopes for the data from weeks 1 to 16 are shown in Table 2 and Figure 4, respectively.

Analysis of Gambling Symptom Assessment Scale scores (Table 2 and Figure 4) demonstrated statistically significant differences among treatment groups in patient-reported gambling symptoms (F=2.48, df=6, 104, p<0.03, global test of intercepts and slopes). Across all nalmefene groups, the mean estimated benefit, compared with the placebo group, was –3.01 points at week 1, and the corresponding benefit during weeks 2–16 was –0.18 point per week, leading to an estimated difference of –5.72 points (95% CI=–9.88 to –1.55) by week 16.

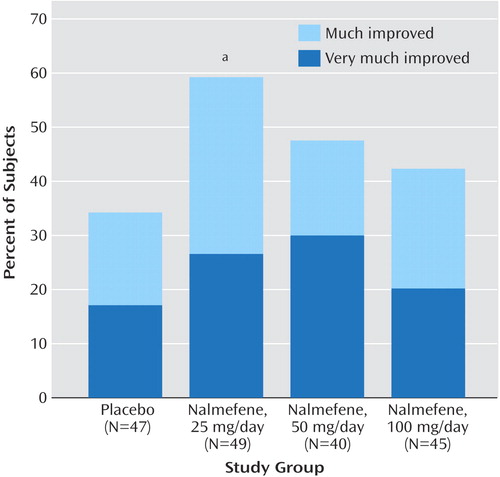

For overall treatment response, subjects with a CGI improvement score of 2 (“much improved”) or 1 (“very much improved”) at the last available evaluation point were considered responders (Figure 5). A total of 59% (29 of 49) of the subjects assigned to receive 25 mg/day of nalmefene were rated by clinicians as “much improved” or “very much improved” at the last evaluation, compared to 34% (16 of 47) of those who received placebo (odds ratio=2.79, 95% CI=1.21–6.41, p<0.04). Although the rates of response in the groups receiving 50 mg/day and 100 mg/day of nalmefene were not significantly different from the rate in the placebo group, 48% (19 of 40) of the subjects assigned to receive 50 mg/day (odds ratio=1.75, 95% CI=0.74–4.16, p=0.77) and 42% (19 of 45) of the subjects assigned to receive 100 mg/day (odds ratio=1.40, 95% CI=0.60–3.28, p=0.59) were considered responders.

The four groups differed significantly in the Sheehan Disability Scale global functioning score (F=2.39, df=6, 99, p<0.04, global test of intercepts and slopes) (Table 2, Figure 4).

Safety and Tolerability

The incidence and severity of adverse experiences in the nalmefene-treated subjects were consistent with those in prior studies (11), and no unusual experiences were reported (Table 3). Because subjects may have reported more than one adverse experience, it was not possible to accurately determine for individual subjects which particular adverse event resulted in treatment discontinuation. Most adverse experiences were of mild to moderate intensity and most commonly occurred during the first week of drug treatment. No clinically significant changes were found in the results of laboratory tests, including liver function tests, during treatment with nalmefene. Mean HAM-A and HAM-D scores remained low throughout the study in all treatment groups, with no statistically significant differences between groups.

Discussion

In this multicenter, randomized, double-blind clinical trial, we found that nalmefene was superior to placebo in the treatment of pathological gambling across a spectrum of illness-specific and global outcome measures. The results demonstrate that nalmefene treatment reduces the symptoms associated with pathological gambling. Of the three fixed doses evaluated, the 25 mg/day and 50 mg/day doses demonstrated superior efficacy, compared to placebo, on the primary efficacy measure (Yale-Brown Obsessive Compulsive Scale Modified for Pathological Gambling total score) and secondary efficacy variables, including the Yale-Brown Obsessive Compulsive Scale Modified for Pathological Gambling behavior and urge/thought subscale scores and the Gambling Symptom Assessment Scale total score. Only the 25 mg/day dose demonstrated efficacy superior to placebo in terms of the overall response to treatment (measured by the CGI). The 100 mg/day dose seemed to confer no additional benefit, compared to the lower dose levels, on any efficacy measure, and the upper limit of the dose range we selected thus seems to have been unnecessarily high.

The efficacy of nalmefene lends support to the hypothesis that pharmacological manipulation of the opiate system may target core symptoms of pathological gambling (10). Opioid antagonists have been effective in treating other addictive disorders involving alcohol, heroin, and cocaine use (6–9). It has been proposed that the efficacy of opioid antagonists in the treatment of addictive disorders involves opioidergic modulation of mesolimbic dopamine circuitry (14). The behavioral effects of opioid antagonist administration include diminished urges to engage in the addictive behavior and longer periods of abstinence (6–11), consistent with a mechanism of action involving ventral striatal dopamine systems (15–17). Further work to define the precise manner in which nalmefene and other opioid antagonists mediate their beneficial effects could enhance treatment strategies for pathological gambling, other impulse control disorders, and substance use disorders.

Nalmefene has been extensively studied, and its lack of potential hepatotoxicity may present a marked advantage over other opioid receptor antagonists, such as naltrexone (11). Adverse events reported in this study were consistent with nalmefene’s previously reported safety profile (11, 18, 19). In contrast to naltrexone, nalmefene has not resulted in hepatotoxicity, regardless of dose. Although there has been concern that opioid antagonists may engender depression (20), there were no increases in the depression scores (HAM-D) or the anxiety scores (HAM-A) during treatment in the subjects in the current study.

To our knowledge this study represents the largest randomized pharmacotherapy trial involving subjects with pathological gambling performed to date, but several limitations exist. First, pathological gambling is a chronic disease that may require long-term therapy. By design, this study did not assess treatment effects beyond the acute 16-week treatment period, and longer-term effects thus require further evaluation. It is possible that a longer course of therapy could result in continued and even greater reductions in gambling symptoms. Alternatively, nalmefene’s therapeutic effects in pathological gambling might not endure beyond 16 weeks. Second, we enrolled subjects seeking pharmacological treatment, not psychotherapy, and we recruited only subjects without current comorbidities. Given these stringent exclusion criteria (e.g., no comorbidity with substance use disorders or bipolar disorder), these results may not generalize completely to the larger population of people with pathological gambling. Third, approximately two-thirds of the subjects discontinued treatment. Although rates of treatment discontinuation in studies of pathological gambling are generally high (up to 49%) (4, 10), discontinuation in this study was most likely a result of poor management of medication side effects. It is likely that the initial dose was too high and that the dose titration at week 2 was too abrupt. Flexible dosing strategies may have allowed for improved tolerability. The relatively high discontinuation rate may compromise the conclusions drawn from this study. Perhaps only those subjects truly committed to stopping gambling tolerated the side effects of nalmefene and stayed in the study. In addition, the elevated rates of nausea for subjects who received nalmefene, compared to those who received placebo, may have jeopardized the blind. Evaluation of lower doses and a slower titration on initiation warrant consideration. Fourth, although subjects were excluded if they had lifetime bipolar I disorder or bipolar II disorder, it is possible that some may have had histories of subsyndromal mania or hypomania. The presence of these subsyndromal symptoms may have led to discontinuation of some subjects taking nalmefene, because the medication could have induced subtle mood destabilization. More detailed assessments of subsyndromal mood symptoms are needed for future studies. Fifth, the subjects assigned to receive placebo demonstrated improvement over time. Although this placebo effect is a confounder, examination of the relative pattern over time demonstrated that the treatment signal appeared to outweigh the placebo effect. Sixth, this study did not include behavioral therapy. Effective behavioral treatments for pathological gambling are emerging (21) and should be considered in conjunction with pharmacotherapies.

This investigation suggests that nalmefene may be effective in the acute treatment of pathological gambling. Although optimal dosing and titration of nalmefene cannot be determined from this study, lower doses and a slower titration should be considered for future studies. As effective treatments for pathological gambling emerge, it becomes increasingly important that physicians and mental health care providers screen for pathological gambling in order to provide timely treatment.

Editor"s note: Namelfene in tablet form is an investigational drug in the United States and not yet approved for general clinical use.

|

|

|

Presented in part at the 43rd annual meeting of the American College of Neuropsychopharmacology, San Juan, P.R., Dec. 12–16, 2004. Received April 12, 2005; revision received July 12, 2005; accepted Sept. 19, 2005. From the Department of Psychiatry, University of Minnesota Medical School; the Department of Psychiatry, Yale University Medical School, New Haven, Conn.; the Department of Psychiatry, Mount Sinai School of Medicine, New York; the Department of Psychiatry, Washington University School of Medicine, St. Louis; and BioTie Therapies Corp., Turku, Finland. Address correspondence and reprint requests to Dr. Grant, Department of Psychiatry, University of Minnesota Medical School, 2450 Riverside Ave., Minneapolis, MN 55454; [email protected] (e-mail).Supported by BioTie Therapies Corp. Dr. Kallio and Mr. Nurminen are employees of BioTie Therapies Corp. No other author has any significant commercial relationships to disclose relative to the study or the article.The authors thank the following principal investigators, who participated in the study for purposes of data collection only: Valerie Arnold, M.D. (Clinical Neuroscience Solutions), Donald Black, M.D. (University of Iowa), Carlos Blanco, M.D. (Columbia University), Anita Kablinger, M.D. (Louisiana State University), David Marks, M.D. (Optimum Health Services), Howard Mason, M.D. (Trimeridian), Thomas Newton, M.D. (UCLA), Nancy Petry, Ph.D. (University of Connecticut), Robert Riesenberg, M.D. (Atlanta Center for Medical Research), Andrew Saxon, M.D. (University of Washington), and Ole Thienhaus, M.D. (University of Nevada). The authors thank Suck Won Kim, M.D., of the University of Minnesota for help with the initial design of the study.

Figure 1. Flow of Subjects Through a 16-Week Multicenter Randomized, Double-Blind, Placebo-Controlled Trial of Nalmefene in the Treatment of Adults With Pathological Gambling

Figure 2. Percentage of Patients Remaining in Treatment Over 16 Weeks in a Placebo-Controlled Trial of Nalmefene in the Treatment of Adults With Pathological Gamblinga

aBaseline Ns are reported for the study groups.

Figure 3. Total Scores on the Yale-Brown Obsessive Compulsive Scale Modified for Pathological Gambling Over 16 Weeks in a Placebo-Controlled Trial of Nalmefene in the Treatment of Adults With Pathological Gamblinga

aDashes show estimated regression lines.

bSignificant difference between the nalmefene and placebo groups (p=0.007, test of equal intercepts and slopes).

cSignificant difference between tbe nalmefene and placebo groups (p<0.02, test of equal intercepts and slopes).

dNonsignificant difference between the nalmefene and placebo groups (p=0.12, test of equal intercepts and slopes).

eSignificant difference between the nalmefene and placebo groups (p=0.006, test of equal intercepts and slopes).

Figure 4. Scores on Secondary Efficacy Measures Over 16 Weeks in a Placebo-Controlled Trial of Nalmefene in the Treatment of Adults With Pathological Gamblinga

aDashes show estimated regression lines.

bSignificant difference between the nalmefene and placebo groups (p<0.02, test of equal intercepts and slopes).

cSignificant difference between the nalmefene and placebo groups (p=0.006, test of equal intercepts and slopes).

dSignificant difference between the nalmefene and placebo groups (p<0.02, test of equal intercepts and slopes).

eSignificant difference between the nalmefene and placebo groups (p<0.03, test of equal intercepts and slopes).

Figure 5. Percentage of Subjects With Clinical Global Impression Improvement Scale Ratings of “Much Improved” or “Very Much Improved” at Endpoint in a Placebo-Controlled Trial of Nalmefene in the Treatment of Adults With Pathological Gambling

aSignificant difference between the nalmefene and placebo groups (odds ratio=2.79, 95% CI=1.21–6.41, p<0.04).

1. Argo TR, Black DW: Clinical characteristics, in Pathological Gambling: A Clinical Guide to Treatment. Edited by Grant JE, Potenza MN. Washington, DC, American Psychiatric Publishing, 2004, pp 39-53Google Scholar

2. Shaffer HJ, Hall MN, Vander Bilt J: Estimating the prevalence of disordered gambling behavior in the United States and Canada: a research synthesis. Am J Public Health 1999; 89:1369–1376Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

3. Potenza MN, Levinson-Miller C, Poling J, Nich C, Rounsaville BJ, Petrakis I: Gambling risk behaviors in alcohol dependent individuals with co-occurring disorders (abstract). Alcohol Clin Exp Res 2005; 28:115AGoogle Scholar

4. Hollander E, Kaplan A, Pallanti S: Pharmacological treatments, in Pathological Gambling: A Clinical Guide to Treatment. Edited by Grant JE, Potenza MN. Washington, DC, American Psychiatric Publishing, 2004, pp 189-205Google Scholar

5. Hollander E, Pallanti S, Allen A, Sood E, Rossi NB: Does sustained-release lithium reduce impulsive gambling and affective instability versus placebo in pathological gamblers with bipolar spectrum disorders? Am J Psychiatry 2005; 162:137–145Link, Google Scholar

6. Volpicelli JR, Alterman AI, Hayashida M, O’Brien CP: Naltrexone in the treatment of alcohol dependence. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1992; 49:876–880Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

7. Anton RF, Moak DH, Waid LR, Latham PK, Malcolm RJ, Dias JK: Naltrexone and cognitive behavioral therapy for the treatment of outpatient alcoholics: results of a placebo-controlled trial. Am J Psychiatry 1999; 156:1758–1764Abstract, Google Scholar

8. Martin WR, Jasinski D, Mansky P: Naltrexone, an antagonist for the treatment of heroin dependence. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1973; 23:784–789Crossref, Google Scholar

9. Kosten TR, Kleber HD, Morgan C: Role of opioid antagonists in treating intravenous cocaine abuse. Life Sci 1989; 44:887–892Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

10. Kim SW, Grant JE, Adson DE, Shin YC: Double-blind naltrexone and placebo comparison study in the treatment of pathological gambling. Biol Psychiatry 2001; 49:914–921Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

11. Mason BJ, Salvato FR, Williams LD, Ritvo EC, Cutler RB: A double-blind, placebo-controlled study of oral nalmefene for alcohol dependence. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1999; 56:719–724Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

12. Hollander E, DeCaria CM, Finkell JN, Begaz T, Wong CM, Cartwright C: A randomized double-blind fluvoxamine/placebo crossover trial in pathological gambling. Biol Psychiatry 2000; 47:813–817Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

13. SAS/STAT User’s Guide, version 8. Cary, NC, SAS Institute, 1999Google Scholar

14. Ikemoto S, Glazier BS, Murphy JM, McBride WJ: Role of dopa mine D1 and D2 receptors in the nucleus accumbens in mediating reward. J Neurosci 1997; 17:8580–8587Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

15. Stewart J: Reinstatement of heroin and cocaine self-administration behavior in the rat by intracerebral application of morphine in the ventral tegmental area. Pharmacol Biochem Behav 1984; 20:917–923Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

16. Matthews RT, German DC: Electrophysiological evidence for excitation of rat ventral tegmental area dopamine neurons by morphine. Neuroscience 1984; 11:617–625Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

17. Broekkamp CL, Phillips AG: Facilitation of self-stimulation behavior following intracerebral microinjections of opioids into the ventral tegmental area. Pharmacol Biochem Behav 1979; 11:289–295Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

18. Salvato FR, Mason BJ: Changes in transaminases over the course of a 12-week, double-blind nalmefene trial in a 38-year-old female subject. Alcohol Clin Exp Res 1994; 18:1187–1189Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

19. Dixon R, Gentile J, Hsu HB, Hsiao J, Howes J, Garg D, Weidler D: Nalmefene: safety and kinetics after single and multiple oral doses of a new opioid antagonist. J Clin Pharmacol 1987; 27:233–239Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

20. Crowley TJ, Wagner JE, Zerbe G, MacDonald M: Naltrexone-induced dysphoria in former opioid addicts. Am J Psychiatry 1985; 142:1081–1084Link, Google Scholar

21. Hodgins DC, Petry NM: Cognitive and behavioral treatments, in Pathological Gambling: A Clinical Guide to Treatment. Edited by Grant JE, Potenza MN. Washington, DC, American Psychiatric Publishing, 2004, pp 169-187Google Scholar