Randomized, Placebo-Controlled Trial of Olanzapine as Maintenance Therapy in Patients With Bipolar I Disorder Responding to Acute Treatment With Olanzapine

Abstract

OBJECTIVE: In a placebo-controlled, double-blind study, the authors investigated the efficacy and safety of olanzapine as monotherapy in relapse prevention in bipolar I disorder. METHOD: Patients achieving symptomatic remission from a manic or mixed episode of bipolar I disorder (Young Mania Rating Scale [YMRS] total score ≤12 and 21-item Hamilton Depression Rating Scale [HAM-D] score ≤8) at two consecutive weekly visits following 6–12 weeks of open-label acute treatment with 5–20 mg/day of olanzapine were randomly assigned to double-blind maintenance treatment with olanzapine (N=225) or placebo (N=136) for up to 48 weeks. The primary measure of efficacy was time to symptomatic relapse into any mood episode (YMRS score ≥15, HAM-D score ≥15, or hospitalization). RESULTS: Time to symptomatic relapse into any mood episode was significantly longer among patients receiving olanzapine (a median of 174 days, compared with a median of 22 days in patients receiving placebo). Times to symptomatic relapse into manic, depressive, and mixed episodes were all significantly longer among patients receiving olanzapine than among patients receiving placebo. The relapse rate was significantly lower in the olanzapine group (46.7%) than in the placebo group (80.1%). During olanzapine treatment, the most common emergent event was weight gain; during the open-label phase, patients who received olanzapine gained a mean of 3.1 kg (SD=3.4). In double-blind treatment, placebo patients lost a mean of 2.0 kg (SD=4.4) and patients who continued to take olanzapine gained an additional 1.0 kg (SD=5.2). CONCLUSIONS: Compared to placebo, olanzapine delays relapse into subsequent mood episodes in bipolar I disorder patients who responded to open-label acute treatment with olanzapine for a manic or mixed episode.

Bipolar I disorder is a recurrent disorder requiring acute and maintenance therapy. Despite therapeutic intervention, relapse rates for patients who are receiving treatment range from 40% to 60%, even after a first lifetime episode (1, 2), with as many as one-half of patients experiencing a second mood episode within a year of recovery (3). These findings strongly suggest that treatment efficacy in relapse prevention requires further study.

Although lithium remains the standard treatment in the prevention of relapse in bipolar disorder, several studies have compared the efficacy of other treatment interventions with lithium in relapse prevention. In a double-blind study comparing divalproex to lithium and placebo over a 12-month maintenance period, time to development of any mood episode did not differ significantly between the two treatment groups or between either treatment group and the placebo group (4). In patients with recent manic/hypomanic symptoms, lamotrigine and lithium were reported to be significantly superior to placebo in prolonging the time to intervention for any mood episode (5). Similarly, in patients with recent depressive symptoms, both lamotrigine and lithium were significantly more effective than placebo at prolonging time to intervention for a mood episode (6).

Further review of the literature revealed few placebo-controlled relapse prevention studies with other psychotropic agents. Several atypical antipsychotics have shown efficacy in treatment of acute mania (olanzapine, aripiprazole, quetiapine, risperidone, ziprasidone) (7–11), but maintenance-phase studies in relapse prevention are lacking, although preliminary results presented at scientific meetings indicated the efficacy of aripiprazole, compared to placebo, in prolonging time to relapse during a 26-week study of patients with recent manic symptoms (12). Accordingly, the objective of the present study was to compare olanzapine with placebo in the prevention of relapse among bipolar I disorder patients who responded to open-label acute olanzapine treatment.

Method

Patients

Inpatients and outpatients age ≥18 years were recruited at 44 sites in the United States and five sites in Romania. The patients met the DSM-IV criteria for an index manic or mixed episode of bipolar I disorder on the basis of their responses to the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV and were required to have a Young Mania Rating Scale (YMRS) total score ≥20 at screening and at the start of open-label acute treatment. In addition, the patients were required to have experienced at least two prior manic or mixed episodes within 6 years of study entry. The study was reviewed and approved by the institutional review board at each site and was conducted in accordance with the ethical principles stated in the most recent version of the Declaration of Helsinki. The patients provided written informed consent before participation.

Study Design

This randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, parallel study included bipolar disorder patients with symptomatic remission after open-label acute treatment with olanzapine for an index manic or mixed episode. In the open-label phase, patients who met the enrollment criteria after a 2–7-day screening period received open-label olanzapine in a flexible dose of 5–20 mg/day for 6–12 weeks. Patients unable to tolerate the minimum dose were discontinued. During the first 3 weeks of open-label treatment, additional antimanic medications were tapered. After the third week, concomitant psychotropic medications were discontinued, with the exception of benzodiazepines (not to exceed 6 mg/day of lorazepam equivalents). Fluoxetine use was discontinued 4 weeks before randomization.

Beginning with week 6 (and no later than week 12), patients in symptomatic remission for at least two consecutive weekly visits became eligible for randomization to the maintenance phase. Symptomatic remission was defined as a YMRS total score ≤12 and a 21-item Hamilton Depression Rating Scale (HAM-D) score ≤8. Patients were randomly assigned in a 2:1 ratio to double-blind maintenance treatment with either 5–20 mg/day of olanzapine or placebo for 48 weeks. This assignment ratio minimized the number of patients receiving placebo.

During double-blind treatment, study drugs were initially dispensed at a dose (in tablets) that was equivalent to that received at the end of open-label treatment. After patients received the initial double-blind dose for 1 day, the daily dose could be adjusted by one tablet per day within the allowed dose range of one to four tablets (5–20 mg/day). Dose decreases of any number of tablets were permitted in response to adverse events. Adherence to the prescribed dosing regimen was determined by returned tablet counts at each treatment visit. Benzodiazepine use was permitted during the double-blind phase but could not exceed 4 mg/day of lorazepam equivalents during the first week and could not exceed 2 mg/day of lorazepam equivalents during the remainder of the study period. In addition, the total duration of benzodiazepine use during the double-blind phase could not exceed 60 cumulative days. Anticholinergic use was permitted. Patients relapsing during double-blind treatment were eligible for 44 weeks of open-label “rescue” treatment with 5–20 mg/day of olanzapine.

Assessments

The primary measure of efficacy was time to symptomatic relapse into any mood episode. Symptomatic relapse into any mood episode was defined as a YMRS total score ≥15, a HAM-D score ≥15, or hospitalization for a manic, mixed, or depressive episode. Symptomatic relapse was further examined by type of mood episode, which included manic (YMRS score ≥15 and HAM-D score <15), depressive (HAM-D score ≥15 and YMRS score <15), or mixed episodes (YMRS score ≥15 and HAM-D score ≥15). The criteria could also be met through hospitalization for the specific mood episode. Similar to the procedures used by Calabrese et al. (6), the attribution of manic, depressed, or mixed episode in patients hospitalized for relapse during the double-blind maintenance phase was made by means of best clinical judgment based on all available information documented in the clinical report form and confirmed, when possible, by YMRS and HAM-D ratings. It is noteworthy that, in these cases of hospitalization, the reliability of clinicians’ ratings concerning the type of mood episode was not assessed. A secondary measure of efficacy was the rate of symptomatic relapse.

The screening assessment included medical history, physical and psychiatric examinations, laboratory profile, and ECG. Vital signs and weight were measured at every visit, and an ECG was obtained at time of randomization, at week 24 of the double-blind phase, and at endpoint. Laboratory testing was conducted at baseline, at 3 weeks, and at the endpoint of the open-label phase, as well as monthly during double-blind treatment and at the final endpoint. Spontaneously reported treatment-emergent adverse events were recorded at each visit. Extrapyramidal symptoms were measured at each visit.

Statistical Methods

Primary analyses were performed on an intent-to-treat basis. Statistical tests were defined a priori, unless stated otherwise. All tests were two-tailed with an alpha level of 0.05 for significance, with the exception of tests of interaction, which employed, as specified by the protocol, an alpha level of 0.10 due to the relative loss of power for tests of interaction, compared to tests of main effects (13). All analyses were performed with SAS software (SAS Institute, Cary, N.C.).

Time-to-relapse curves were estimated by using the Kaplan-Meier technique and were compared statistically by using the log-rank test. Median estimates of time to relapse are provided when the probability of survival was ≤0.50. Otherwise, time to relapse is given by using 25th percentile estimates or is listed as not calculable if the probability of the event was ≤0.25. Hazard ratios with 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were used to characterize the relative risk of relapse derived from univariate Cox regression analyses. Two post hoc stratified Cox regression analyses were performed for time to relapse; in one of these analyses, site was used as a stratifier, and in the other, country was used as a stratifier. A Cox regression analysis of the effect of length of remission (in days) before randomization included terms for treatment, days of remission, and their interaction, with single degree of freedom contrasts used to compare estimated risks of relapse for patients with 7, 14, 21, and 28 days of prerandomization remission. Odds ratio estimates with 95% CIs and the number needed to treat with 95% CI were used to characterize differences for overall rates of relapse. In the ratio estimates for efficacy, data for the placebo group were used as the referent. In addition, post hoc analyses of relapse were performed for the subset of patients with a minimum of 2 or 8 weeks of double-blind exposure while in remission. Subgroup time-to-relapse analyses were performed by using a Cox regression model that included terms for treatment, subgroup, and the treatment-by-subgroup interaction.

Analysis of variance models were used to evaluate baseline characteristics and last-observation-carried-forward changes in continuous safety data. The models included terms for treatment, site, and treatment-by-site interaction. Change (last observation carried forward) during the open-label phase was compared with zero by using a one-sample Student’s t test. For analysis of proportions, Fisher’s exact test was used. Incidence rates for safety events were characterized by an estimate of the relative risk with 95% CI; estimates were constructed with data from the placebo group as the referent. In the event of zero incidence in the reference group, the absolute risk reduction with 95% CI was provided. For last-observation-carried-forward change in extrapyramidal symptom rating scales, differences between groups were assessed with the nonparametric Wilcoxon’s rank-sum test.

Results

Patient Disposition and Characteristics

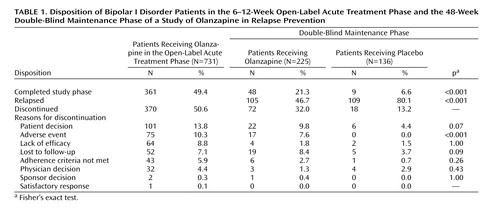

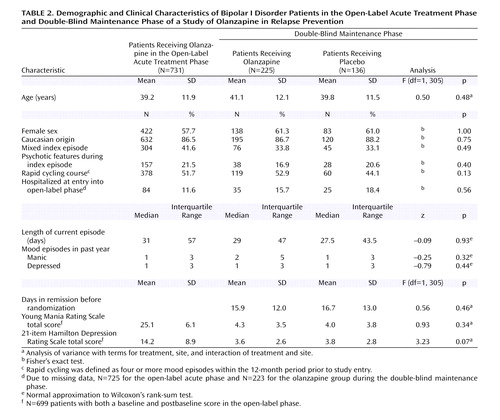

Of 910 patients who entered screening, 731 received open-label olanzapine as acute therapy. During open-label treatment, 361 (49.4%) met symptomatic remission criteria and were randomly assigned to receive either olanzapine (N=225) or placebo (N=136) in the double-blind maintenance phase. Rates of study completion and reasons for discontinuation in either the open-label or double-blind phases are reported in Table 1. The rates of study completion for patients who were randomly assigned to treatment groups in the double-blind maintenance phase were 21.3% (N=48) for the olanzapine group and 6.6% (N=9) for the placebo group. The characteristics of the patients who entered the open-label acute treatment phase and for each treatment group within the double-blind maintenance phase are reported in Table 2. During the double-blind phase, the patients who received olanzapine had a longer time to discontinuation (median=83 days) than the patients who received placebo (median=26 days) (log-rank χ2=27.0, df=1, p<0.001). The rate of discontinuation due to an adverse event was significantly greater in the olanzapine group (N=17, 7.6%) than in the placebo group (N=0, 0%) (p<0.001, Fisher’s exact test). The mean daily doses of olanzapine were 11.8 mg (SD=7.5) in the open-label acute treatment phase and 12.5 mg (SD=5.0) in the double-blind maintenance phase. The mean study drug adherence rates during double-blind treatment, defined as the number of days a patient was adherent to the medication regimen divided by total number of days of treatment, were 93.9% in the olanzapine group and 93.1% in the placebo group. Rates of concomitant benzodiazepine use were 26.7% in the olanzapine group and 36.0% in the placebo group, not a significant difference (p=0.08, Fisher’s exact test); mean daily doses were 1.8 mg/day (SD=1.5) of lorazepam equivalents in the olanzapine group and 1.9 mg/day (SD=1.7) of lorazepam equivalents in the placebo group. During double-blind treatment, the rate of anticholinergic use was low (4.4% in each group).

Prevention of Symptomatic Relapse

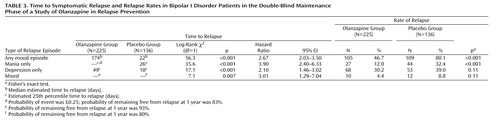

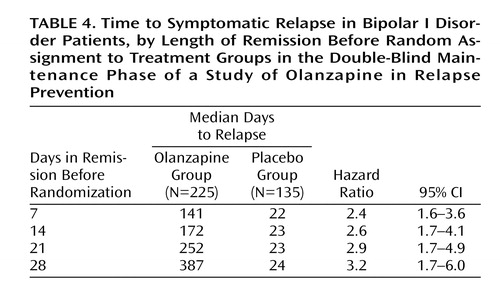

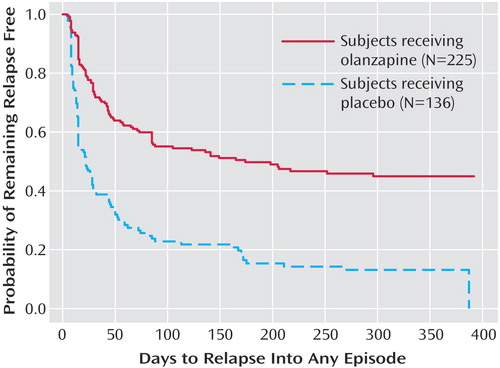

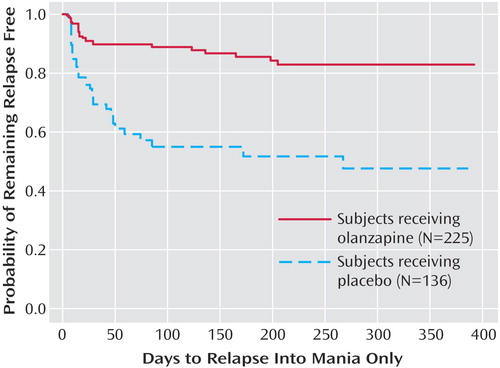

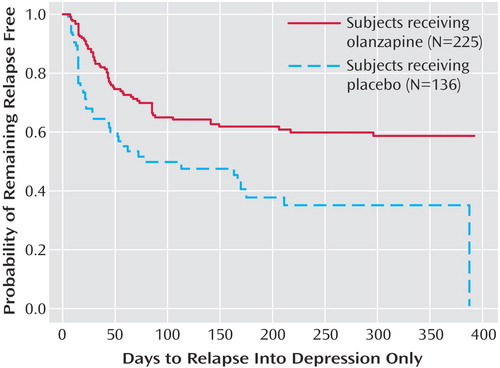

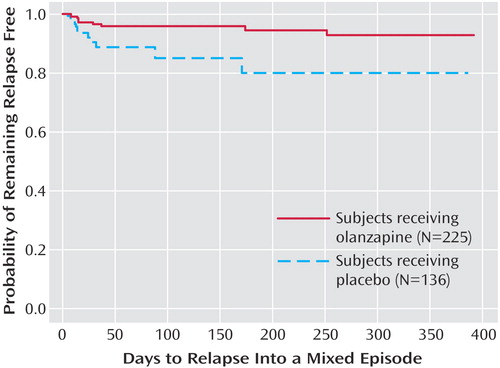

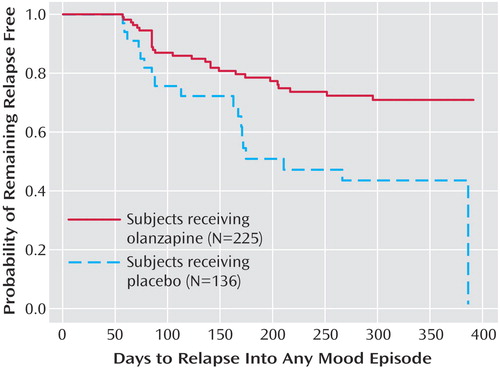

The primary outcome measure, time to symptomatic relapse into any mood episode during double-blind maintenance treatment, was significantly longer for patients who received olanzapine than for patients who received placebo (Table 3). The median estimated time to symptomatic relapse into any mood episode was 22 days for the placebo group and 174 days for the olanzapine group (Figure 1) (log-rank χ2=56.3, df=1, p<0.001). Post hoc stratified Cox regression analysis with site or country as stratification factors provided results that were similar to those of the primary analysis (site: hazard ratio=2.89, p<0.001, 95% CI=2.15–3.88; country: hazard ratio=2.79, p<0.001, 95% CI=2.13–3.66). For relapse into mania (Figure 2), the estimated 25th percentile time to relapse was 26 days for the patients who received placebo and was not calculable for the olanzapine group; however, the patients who received olanzapine had an 83% probability of remaining free from manic relapse for at least 1 year (χ2=35.6, df=1, p<0.001). For relapse into depression (Figure 3), the estimated 25th percentile time to relapse was 18 days for the placebo group and 49 days for the olanzapine group (χ2=17.1, df=1, p<0.001). Because of the small number of events, time to mixed episode relapse (Figure 4) could not be estimated for either group; however, at 1 year, the probability of remaining free from a mixed episode relapse was 80% for the placebo group and 93% for the olanzapine group (χ2=7.1, df=1, p=0.007). Post hoc analyses were conducted to determine if time in remission was associated with time to relapse. A proportional hazards regression analysis that included length of remission before randomization as a covariate was used to predict time to symptomatic relapse into any mood episode. Remission lengths of 7, 14, 21, and 28 days had minimal effects on the estimated median time to relapse for patients who received placebo (Table 4). The data, however, show that longer time in remission before randomization was numerically but not statistically significant associated with longer time to relapse (χ2=2.61, df=1, p=0.11).

Rates of relapse during the double-blind maintenance phase are reported in Table 3. Symptomatic relapse into any mood episode occurred in 105 (46.7%) of 225 patients in the olanzapine group and 109 (80.1%) of 136 patients in the placebo group (odds ratio=4.61, 95% CI=2.81–7.58). These risk-of-relapse results correspond to a number needed to treat of 3.0 (95% CI=2.3–4.1), indicating that treating three patients with olanzapine prevents one relapse that would otherwise have occurred with placebo. It is noteworthy that most relapses were identified on the basis of YMRS and/or HAM-D scores; the relapses of only nine patients (olanzapine group: N=2; placebo group: N=7) involved hospitalization, and the YMRS or HAM-D criteria were met by eight of these nine relapsing patients when they were assessed within a few days after hospital admission. Post hoc analyses were conducted to control for early relapses in the double-blind phase after discontinuation of open-label treatment with olanzapine. Analyses of relapse were performed with data from the subset of patients who remained in symptomatic remission during the double-blind phase for at least the first 2 weeks (olanzapine group: N=204; placebo group: N=87) and the first 8 weeks (olanzapine group: N=112; placebo group: N=34). Among patients with a minimum remission time of 2 weeks during the double-blind phase, 43.1% (N=88) of those who received olanzapine experienced symptomatic relapse to any mood episode, compared to 71.3% (N=62) of those who received placebo (p<0.001, odds ratio=3.27, 95% CI=1.90–5.61). When patients with relapses during the first 8 weeks of the double-blind phase were excluded, symptomatic relapse to any mood episode occurred in 25.0% (N=28) of the patients who received olanzapine and 52.9% (N=18) of the patients who received placebo (p=0.003, odds ratio=3.38, 95% CI=1.52–7.49); furthermore, the median estimated time to symptomatic relapse into any mood episode was significantly longer for the olanzapine patients (median undefined) than for the placebo patients (median=211 days) (Figure 5) (χ2=9.0, df=1, p<0.003).

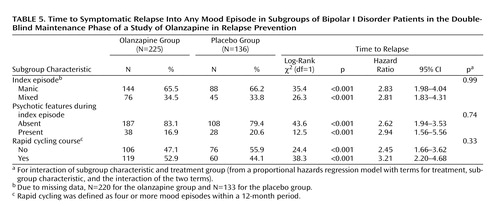

Relapse data were analyzed in terms of the patients’ demographic and baseline clinical characteristics. Factors included age (<40 versus ≥40 years), sex, racial origin (Caucasian versus other), presence versus absence of psychotic features, nature of the index episode (manic versus mixed), and presence versus absence of a rapid cycling course. Analyses of time to symptomatic relapse into any mood episode revealed no interactions between the treatment groups and subgroup characteristics. Table 5 reports the results for nature of the index episode and the presence or absence of psychotic features and rapid cycling. Separate analyses of data from patients with a manic index episode or a mixed index episode revealed that, in both groups, time to relapse into any mood episode was significantly longer in patients who received olanzapine than in patients who received placebo. In addition, olanzapine treatment significantly lengthened time to symptomatic relapse in patients with and without a history of a rapid cycling course, as well as in those with and without psychotic features.

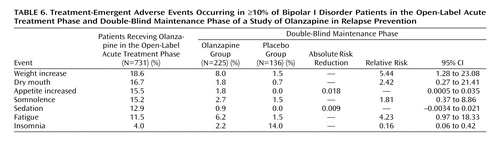

Safety Results

Table 6 lists treatment-emergent adverse events reported by ≥10% of the patients during either the open-label acute treatment phase or the double-blind maintenance phase. The most common adverse events reported during the open-label phase were weight gain, dry mouth, increased appetite, and somnolence. During the double-blind phase, adverse events reported by patients who received olanzapine were weight gain and fatigue. Insomnia was more frequently reported by patients who received placebo. Serious adverse events, the majority of which were related to worsening of the illness, were reported by 10 (7.4%) of the 136 patients in the placebo group and seven (3.1%) of the 225 patients who received olanzapine (relative risk=0.42, 95% CI=0.16–1.09).

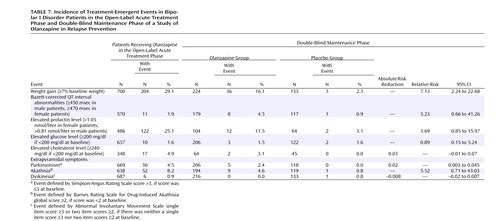

Incidence rates for treatment-emergent adverse events during the open-label and double-blind phases are presented in Table 7. During the open-label acute treatment phase, patients gained a mean of 3.0 kg (SD=3.4) of body weight. After randomization, the patients receiving placebo lost a mean of 2.0 kg (SD=4.4) and the patients receiving olanzapine gained an additional 1.0 kg (SD=5.2). Among the 357 patients who were subsequently randomly assigned to the double-blind treatment groups, 125 (35.0%) experienced an increase in baseline weight of ≥7% during the open-label phase. Among these 125 patients, 14 (17.7%) of 79 patients who received olanzapine and one (2.2%) of 46 patients who received placebo experienced an increase in weight of ≥7% from the point of randomization in the double-blind phase. Among the 232 (65.0%) patients who gained <7% of baseline weight during the open-label phase, 22 (15.2%) of 145 patients who received olanzapine and two (2.3%) of 87 patients who received placebo experienced an increase of ≥7% in the double-blind phase. Electrocardiographic abnormalities in Bazett-corrected QT intervals were found in eight (4.5%) of 179 patients who received olanzapine and one (0.9%) of 117 patients who received placebo (Table 7).

Data for treatment-emergent prolactin abnormalities by phase of the study are presented in Table 7. Considering all olanzapine exposures, regardless of study phase, treatment-emergent elevation in prolactin level occurred in 134 (27.0%) of 496 patients. Among these 134 patients with treatment-emergent abnormalities associated with olanzapine, the distribution of abnormal values in terms of quartiles (25th, 50th, and 75th percentiles) and maximum prolactin value (in nmol/liter) were 0.90, 0.97, 1.22, and 2.51, respectively, for male patients and 1.21, 1.47, 2.02, and 3.71, respectively, for female patients. During the open-label phase, prolactin abnormalities occurred in 64 (29.4%) of 218 patients who were ultimately randomly assigned to treatment groups in the double-blind phase. Among these 64 patients, prolactin abnormalities occurred in the double-blind phase in 19 (44.2%) of 43 patients randomly assigned to receive olanzapine and in two (9.5%) of 21 patients randomly assigned to receive placebo. Increases in nonfasting glucose (mean=5.3 mg/dl, SD=34.4) and cholesterol (mean=10.7 mg/dl, SD=29.6) levels were reported during the open-label phase. Three patients in the olanzapine group and two in the placebo group had treatment-emergent elevations in glucose level during the double-blind phase; the maximum glucose values were 249.8, 273.8, and 293.8 mg/dl, respectively, for the three patients who received olanzapine and 211.8 and 212.4 mg/dl, respectively, for the two patients who received placebo. Two patients in the olanzapine group had treatment-emergent elevations in cholesterol level; maximum cholesterol values for those patients were 283.2 and 248.2 mg/dl, respectively. No patient in the placebo group had an elevation in cholesterol level.

Incidence rates of extrapyramidal symptoms were low in both the open-label and double-blind phases. No differences were found between the olanzapine and placebo groups in rates of treatment-emergent parkinsonism, akathisia, and dyskinesia (Table 7).

Discussion

To our knowledge, this study is the first published placebo-controlled relapse prevention study of an antipsychotic (typical or atypical) in patients with bipolar I disorder. The results presented here describe the efficacy of olanzapine monotherapy in preventing relapse in patients who responded to open-label acute treatment with olanzapine for a manic or mixed episode.

In this study, the primary efficacy endpoint was time to symptomatic relapse into any mood episode. Olanzapine significantly lengthened the time to relapse by almost eightfold over placebo (median of 174 days, compared to 22 days). Furthermore, olanzapine prolonged the time to symptomatic relapse into all three types of mood episodes. On the basis of differences in hazard ratios, olanzapine appears to be more effective in preventing manic and mixed episodes than depressive episodes. To our knowledge, these results are the first estimates of relapse into a mixed mood episode to be published. The patients who received olanzapine had significantly longer times to symptomatic mixed episode relapse, compared to the patients who received placebo.

To provide a pragmatic method to ascertain the possible clinical usefulness of long-term olanzapine, analyses of the number needed to treat were conducted. The results showed a large clinical maintenance effect size and suggested that treating three patients with olanzapine prevents one relapse that would otherwise have occurred with placebo. Subgroup analyses revealed that olanzapine treatment significantly lengthened the time to relapse in patients with a mixed index episode; to our knowledge, there are no previous reports in the literature of placebo-controlled studies of relapse prevention in patients with mixed episodes. In addition, patients with a history of rapid cycling experienced longer times to symptomatic relapse with olanzapine, compared to placebo. To our knowledge, this study represents the first instance in which a long-term treatment intervention was shown to have separated from placebo in its effects in patients with rapid-cycling bipolar I disorder. Furthermore, to our knowledge, this study contained the largest data set for patients with rapid cycling. This aspect of the study may have resulted in a larger number of depressive relapses in the study group, compared with other studies, because depressive episodes have been described as a predominant characteristic of a rapid-cycling course (14). In addition, placebo-controlled maintenance studies have historically revealed a trend in which the polarity of the index episode in patients with bipolar I disorder predicts the polarity of relapse (15).

This relapse prevention study has several limitations. First, because the design included a 48-week placebo-controlled maintenance phase, patients may have been reluctant to continue beyond open-label therapy and accept the risk of assignment to placebo, thus limiting the generalizability of the results. Second, the maintenance phase of this study tested an enriched sample. Random assignment of only those patients who responded to acute olanzapine therapy resulted in a more homogeneous population for double-blind treatment. Therefore, the results may be generalized only to patients who respond to olanzapine in acute treatment.

In this study design, random assignment to a double-blind treatment group followed a brief remission period (minimum of 1 week). The brevity of responder status may suggest that subsequent relapse could be identified as a recrudescence of the index episode. However, the results of post hoc analyses suggested that time in remission before randomization was not associated with risk of relapse. In addition, the absence of an olanzapine taper period for patients entering double-blind treatment with assignment to placebo may represent a study limitation. To examine this possibility, post hoc analyses were conducted to exclude early relapses, and analyses of data from only those patients who remained in remission for at least 2 or 8 weeks of double-blind treatment supported the efficacy of olanzapine. Last, the relatively low rates of study completion constitute a possible study limitation; however, if patients with relapses during the double-blind maintenance phase are included in the proportion of study completers, the completion rates were 68.0% (153 of 225) for the olanzapine group and 86.8% (118 of 136) for the placebo group. The lower rate of study completion for olanzapine-treated patients without relapse may be partly attributable to side effects associated with long-term olanzapine treatment, such as weight gain (16). Olanzapine-treated patients stayed in the study longer than those who received placebo and thus had greater exposure to possible adverse effects. Therefore, clinicians are advised to monitor weight changes and to consider alternative therapeutic strategies if clinically indicated.

In conclusion, the study results suggest that, compared to placebo, olanzapine monotherapy significantly delays relapse into subsequent mood episodes in bipolar I disorder patients who responded to acute olanzapine treatment for a manic or mixed episode.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Presented at the 4th European Stanley Conference on Bipolar Disorders, Aarhus, Denmark, Sept. 23–25, 2004; International Congress of the World Federation of Societies of Biological Psychiatry, Sydney, Australia, Feb. 9–13, 2004; Regional Group Conference of the International Society for Bipolar Disorders, Sydney, Australia, Feb. 5–7, 2004; 4th International Forum for Mood and Anxiety Disorders, Monte Carlo, Monaco, Nov. 26–29, 2003; 53rd annual meeting of the Canadian Psychiatric Association, Halifax, Nova Scotia, Oct. 30–Nov. 3, 2003; 16th European College of Neuropsychopharmacology Congress, Prague, Sept. 20–24, 2003; World Psychiatric Association Thematic Conference, Vienna, June 19–22, 2003; 5th International Conference on Bipolar Disorder, Pittsburgh, June 12–14, 2003; and 156th annual meeting of the American Psychiatric Association, San Francisco, May 17–22, 2003. From Lilly Research Laboratories; the Department of Psychiatry, Harvard Medical School/McLean Hospital, Belmont, Mass.; the Department of Psychiatry, Case Western University School of Medicine/University Hospitals of Cleveland, Cleveland; the Department of Psychiatry, Harvard Medical School/Massachusetts General Hospital; Boston; Northwest Behavioral Medicine and Northwest Behavioral Research Center; Marietta, Ga.; the Department of Psychiatry, Bellevue Hospital, New York; and the Department of Psychiatry, University of Texas Health Science Center, San Antonio, Tex. Address correspondence and reprint requests to Dr. Tohen, Lilly Research Laboratories, Indianapolis, IN 46285; [email protected] (e-mail).This work was sponsored by Lilly Research Laboratories.

Figure 1. Kaplan-Meier Survival Analysis of Time to Symptomatic Relapse Into Any Mood Episode for Bipolar I Disorder Patients in the Double-Blind Maintenance Phase of a Study of Olanzapine in Relapse Preventiona

aRelapse based on Young Mania Rating Scale score ≥15, 21-item Hamilton Depression Rating Scale score ≥15, or hospitalization for a mood episode. Estimated median time to relapse was 174 days for olanzapine patients and 22 days for placebo patients (log-rank χ 2=56.3, df=1, p<0.001; hazard ratio=2.67, 95% CI=2.03–3.50)

Figure 2. Kaplan-Meier Survival Analysis of Time to Symptomatic Relapse Into Mania Only for Bipolar I Disorder Patients in the Double-Blind Maintenance Phase of a Study of Olanzapine in Relapse Preventiona

aRelapse based on Young Mania Rating Scale score ≥15 and 21-item Hamilton Depression Rating Scale score <15, or hospitalization for mania. Estimated 25th percentile time to relapse was not calculable for olanzapine patients and was 26 days for placebo patients (log-rank χ 2=35.6, df=1, p<0.001; hazard ratio=3.90, 95% CI=2.40–6.33).

Figure 3. Kaplan-Meier Survival Analysis of Time to Symptomatic Relapse Into Depression Only for Bipolar I Disorder Patients in the Double-Blind Maintenance Phase of a Study of Olanzapine in Relapse Preventiona

aRelapse based on 21-item Hamilton Depression Rating Scale score ≥15 and Young Mania Rating Scale score <15, or hospitalization for depression. Estimated 25th percentile time to relapse was 49 days for olanzapine patients and 18 days for placebo patients (log-rank χ 2=17.1, df=1, p<0.001; hazard ratio=2.10, 95% CI=1.46–3.02).

Figure 4. Kaplan-Meier Survival Analysis of Time to Symptomatic Relapse Into a Mixed Episode for Bipolar I Disorder Patients in the Double-Blind Maintenance Phase of a Study of Olanzapine in Relapse Preventiona

aRelapse based on Young Mania Rating Scale score ≥15 and 21-item Hamilton Depression Rating Scale score ≥15, or hospitalization for a mixed episode. Estimated 25th percentile time to relapse was not calculable for either group, but the probability of remaining free from a mixed episode relapse at 1 year was 93% for the olanzapine patients and 80% for the placebo patients (χ2=7.1, df=1, p=0.007; hazard ratio=3.01, 95% CI=1.29–7.04).

Figure 5. Kaplan-Meier Survival Analysis of Time to Symptomatic Relapse Into Any Mood Episode for Bipolar I Disorder Patients Remaining in Remission During the Initial 8 Weeks of the Double-Blind Maintenance Phase of a Study of Olanzapine in Relapse Preventiona

aRelapse based on Young Mania Rating Scale score ≥15, 21-item Hamilton Depression Rating Scale score ≥15, or hospitalization for a mood episode. Median estimated time to symptomatic relapse into any mood episode was significantly longer for olanzapine patients (median undefined) than for placebo patients (median=211 days) (χ2=9.0, df=1, p<0.003).

1. Goldberg JF, Harrow M, Grossman LS: Recurrent affective syndromes in bipolar and unipolar mood disorders at follow-up. Br J Psychiatry 1995; 166:382–385Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

2. Tohen M, Zarate CA Jr, Hennen J, Khalsa HM, Strakowski SM, Gebre-Medhin P, Salvatore P, Baldessarini RJ: The McLean-Harvard First-Episode Mania Study: prediction of recovery and first recurrence. Am J Psychiatry 2003; 160:2099–2107Link, Google Scholar

3. Tohen M, Waternaux CM, Tsuang MT: Outcome in mania: a 4-year prospective follow-up of 75 patients utilizing survival analysis. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1990; 47:1106–1111Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

4. Bowden CL, Calabrese JR, McElroy SL, Gyulai L, Wassef A, Petty F, Pope HG Jr, Chou JC, Keck PE Jr, Rhodes LJ, Swann AC, Hirschfeld RM, Wozniak PJ (Divalproex Maintenance Study Group): A randomized, placebo-controlled 12-month trial of divalproex and lithium in treatment of outpatients with bipolar I disorder. Arch Gen Psychiatry 2000; 57:481–489Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

5. Bowden CL, Calabrese JR, Sachs G, Yatham LN, Asghar SA, Hompland M, Montgomery P, Earl N, Smoot TM, DeVeaugh-Geiss J: A placebo-controlled 18-month trial of lamotrigine and lithium maintenance treatment in recently manic or hypomanic patients with bipolar I disorder. Arch Gen Psychiatry 2003; 60:392–400Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

6. Calabrese JR, Bowden CL, Sachs G, Yatham LN, Behnke K, Mehtonen OP, Montgomery P, Ascher J, Paska W, Earl N, DeVeaugh-Geiss J: A placebo-controlled 18-month trial of lamotrigine and lithium maintenance treatment in recently depressed patients with bipolar I disorder. J Clin Psychiatry 2003; 64:1013–1024Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

7. Sachs G, Chengappa KN, Suppes T, Mullen JA, Brecher M, Devine NA, Sweitzer DE: Quetiapine with lithium or divalproex for the treatment of bipolar mania: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study. Bipolar Disord 2004; 6:213–223Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

8. Hirschfeld RMA, Keck PE Jr, Kramer M, Karcher K, Canuso C, Eerdekens M, Grossman F: Rapid antimanic effect of risperidone monotherapy: a 3-week multicenter, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Am J Psychiatry 2004; 161:1057–1065Link, Google Scholar

9. Keck PE Jr, Versiani M, Potkin S, West SA, Giller E, Ice K (Ziprasidone in Mania Study Group): Ziprasidone in the treatment of acute bipolar mania: a three-week, placebo-controlled, double-blind, randomized trial. Am J Psychiatry 2003; 160:741–748Link, Google Scholar

10. Tohen M, Sanger TM, McElroy SL, Tollefson GD, Chengappa KNR, Daniel DG, Petty F, Centorrino F, Wang R, Grundy SL, Greaney MG, Jacobs TG, David SR, Toma V (Olanzapine HGEH Study Group): Olanzapine versus placebo in the treatment of acute mania. Am J Psychiatry 1999; 156:702–709Abstract, Google Scholar

11. Jones M, Huizar K: Randomised, double-blind, controlled data on the treatment of mania with quetiapine (abstract). Eur Psychiatry 2004; 19(suppl 1):206SGoogle Scholar

12. Sanchez R, Marcus R, Carson WH, McQuade RD, Iwamota T, Stock E: Aripiprazole in the maintenance treatment of bipolar disorder (abstract). Eur Psychiatry 2004; 19(suppl 1):204SGoogle Scholar

13. Brookes ST, Whitely E, Egger M, Smith GD, Mulheran PA, Peters TJ: Subgroup analyses in randomized trials: risks of subgroup-specific analyses; power and sample size for the interaction test. J Clin Epidemiol 2004; 57:229–236Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

14. Calabrese JR, Shelton MD, Bowden CL, Rapport DJ, Suppes T, Shirley ER, Kimmel SE, Caban SJ: Bipolar rapid cycling: focus on depression as its hallmark. J Clin Psychiatry 2001; 62(suppl 14):34-41Google Scholar

15. Calabrese JR, Vieta E, El-Mallakj R, Findling RL, Youngstrom EA, Elhaj O, Prashant P, Pies R: Mood state at study entry as predictor of risk of relapse and spectrum of efficacy in bipolar maintenance studies. Biol Psychiatry 2004; 56:867–873Crossref, Google Scholar

16. Kinon BJ, Basson BR, Gilmore JA, Tollefson GD: Long-term olanzapine treatment: weight change and weight-related health factors in schizophrenia. J Clin Psychiatry 2001; 62:92–100 Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar