Six-Month, Blinded, Multicenter Continuation Study of Ziprasidone Versus Olanzapine in Schizophrenia

Abstract

OBJECTIVE: The authors’ goal was to compare the efficacy and tolerability of 6 months’ treatment with flexible-dose ziprasidone and olanzapine in patients with schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder. METHOD: Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale (BPRS) scores and Clinical Global Impression (CGI) severity scores were obtained for 126 responders to a 6-week acute study of olanzapine and ziprasidone during a blinded 6-month continuation study and optional extension study. RESULTS: Comparable improvements in BPRS and CGI severity scores were seen with both drugs. Olanzapine produced significant increases from acute-study baseline values in weight and body mass index and within-group increases in total cholesterol, low-density lipoprotein cholesterol, and fasting insulin. Between-group differences were not significant for lipids and insulin. Mean QTc values at endpoint were 407.1 msec (baseline mean=406.0 msec) and 394.4 msec (baseline mean=399.7 msec) for ziprasidone and olanzapine, respectively. No patient had a QTc interval ≥500 msec. CONCLUSIONS: Ziprasidone and olanzapine had comparable long-term efficacy; olanzapine was associated with significant weight gain and metabolic alterations.

In our previous 6-week acute study of ziprasidone and olanzapine in 269 patients with schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder (1), both drugs showed comparable efficacy. Olanzapine, however, was associated with significant increases in body weight, total cholesterol, triglycerides, low-density lipoprotein cholesterol, and fasting insulin. Responders in the acute study (Clinical Global Impression [CGI] improvement score ≤2 or ≥20% reduction in symptom severity according to Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale total score) were enrolled in a 6-month, double-blind, multicenter continuation study, which compared the long-term efficacy and tolerability of these agents as maintenance treatment. After completion of the 6-month continuation study, patients could opt into a blinded extension study lasting up to 2 years. Data from the continuation study and extension study are reported here.

Method

Entry criteria for the acute study (1) included a primary DSM-IV diagnosis of schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder. Enrollment criteria for the 6-month continuation study included 1) completion of 6 weeks’ double-blind treatment with ziprasidone or olanzapine, 2) a CGI improvement score of ≤2 or a ≥20% reduction in Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale total score at acute-study endpoint, and 3) outpatient status. Dosing for the continuation phase was flexible (ziprasidone, 40, 60, or 80 mg b.i.d.; olanzapine, 5, 10, or 15 mg/day) and based on investigators’ clinical judgment.

Primary efficacy measures were ratings on the Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale (BPRS) and the severity rating on the CGI. Other efficacy measures included the total rating on the Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale as well as positive and negative subscale scores and the rating on the Calgary Depression Scale for Schizophrenia.

Key safety assessments included the following: 1) vital signs, body weight, and body mass index; physical examination; clinical laboratory tests; and ECGs and 2) ratings on the Extrapyramidal Symptom Rating Scale, Barnes Rating Scale for Drug-Induced Akathisia, and Abnormal Involuntary Movement Scale.

The acute-study baseline (day 0 of the 6-week study) was used to evaluate the long-term benefit of the study drugs across acute and maintenance treatment, and the 6-month continuation-study baseline (acute-study 6-week endpoint) was used to evaluate response maintenance. Mean changes in long-term efficacy and movement disorder measures are reported from baseline to 6 months; safety and tolerability data are reported as the last observation through the optional extension study.

For the CGI severity and BPRS ratings, total analyses were based on the intent-to-treat study group, used the last-observation-carried-forward method, and were tested by using analysis of covariance (ANCOVA) (all tests were two-sided; significance was set as p≤0.05). Other efficacy measures (Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale scores, Calgary Depression Scale for Schizophrenia scores, factors derived from the BPRS, and Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale scores), QTc values, and movement disorders were analyzed by ANCOVA. Kaplan-Meier analysis compared time with maintenance of treatment response for those patients who completed 6 weeks of the continuation study with ≥20% improvement from acute-study baseline in Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale total score. All tolerability analyses used the acute-study baseline visit (1).

Results

The distribution of diagnoses (>60% of the patients had schizophrenia) and duration of illness were comparable in the 126 continuation-study patients assigned to ziprasidone (N=55) or olanzapine (N=71). At 6 months, mean doses for ziprasidone and olanzapine were 135.2 mg/day (range=78–162) and 12.6 mg/day (range=5–15), respectively. Median study duration throughout all phases was 195 days for both treatment groups (range=43–814).

Discontinuation rates from acute-study baseline through continuation-study and optional extension-study last endpoints were similar for patients given ziprasidone (69.1% [N=38]) or olanzapine (70.4% [N=50]); however, only five (9.1%) ziprasidone-treated and six (8.5%) olanzapine-treated patients discontinued for reasons related to the study drug. Patient default (ziprasidone [34.5%, N=19], olanzapine [26.8%, N=19]) or adverse events considered unrelated to the study drug (ziprasidone [12.7%, N=7], olanzapine [25.4%, N=18]) were the primary reasons for discontinuation.

At 6 months, Kaplan-Meier survival curves showing time to a significant symptom exacerbation (i.e., ≥20% worsening of Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale total score and a CGI severity score ≥3) were not significantly different between the two treatment groups (p=0.62, log-rank test). Response maintenance rates at 6 months were 85.5% (N=47) for ziprasidone and 84.5% (N=60) for olanzapine.

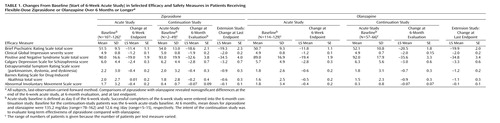

Both treatments produced long-term improvements from acute-study baseline to continuation-study endpoint in BPRS total, CGI severity, Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale total, and Calgary Depression Scale for Schizophrenia scores as well as in Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale positive and negative subscale scores (n.s. between treatment groups). Both treatments also produced sustained improvements in measures of movement disorders (Table 1). At 6-month evaluation, mean Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale total scores decreased from acute-study baseline (n.s. for all). There were modest increases in Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale total scores from continuation-study baseline (acute-study week 6) to 6-month evaluation (n.s.), which may be attributed to the low scores both treatment groups achieved in the acute study.

Olanzapine was associated with significant within-group increases from acute-study baseline in mean body weight (4.97 kg) (p<0.01) and body mass index (1.31) (p<0.01) at continuation-study endpoint; however, ziprasidone was associated with significant between-group reductions in weight (–0.82 kg) (p=0.0008) and body mass index (–0.59) (p=0.002). Kaplan-Meier estimates of probability of weight gain ≥7% after first dose showed a higher probability of rapid weight gain associated with olanzapine than with ziprasidone (respectively, 0.03 versus 0.02 at day 7, 0.4 versus 0.05 at day 28, and 0.68 versus 0.23 at day 154) (p=0.001, log-rank test).

There were significant within-group median increases from baseline in fasting insulin (2.0 μU/ml) (p=0.003), total cholesterol (13.0 mg/dl) (p=0.03), and low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (17.0 mg/dl) (p=0.04) with olanzapine and corresponding nonsignificant changes with ziprasidone in fasting insulin (1.0 μU/ml) (p=0.14), total cholesterol (–1.0 mg/dl) (p=0.98), and low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (9.0 mg/dl) (p=0.29). Between-group changes were not significant. Olanzapine was also associated with significant median increases from baseline in aspartate aminotransferase (6.0 U/liter) (p=0.0006) and alanine aminotransferase (7.0 U/liter) (p=0.002). Neither treatment significantly affected vital signs.

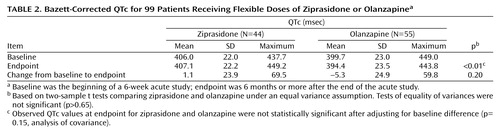

The mean QTc (Bazett correction) at endpoint was 407.1 msec in 44 ziprasidone patients and 394.4 msec in 55 olanzapine patients (Table 2). Notably, observed QTc mean changes for ziprasidone and olanzapine were not statistically significant between the two treatment groups.

Overall, treatment-related adverse events (mostly mild to moderate) were reported in 58.2% (N=32) of the ziprasidone-treated patients and 66.2% (N=47) of the olanzapine-treated patients, with weight gain seen only in the olanzapine group (16.9% [N=12]). The most common treatment-related adverse events involved the nervous system (50.9% [N=28] and 46.5% [N=33] for ziprasidone and olanzapine, respectively) and were predominantly mild to moderate in severity. Digestive system adverse events were seen in 27.3% (N=15) and 22.5% [N=16] of ziprasidone-treated and olanzapine-treated patients, respectively; the vast majority of these were mild, a few moderate, and none severe. More metabolic and nutritional adverse events were seen in olanzapine-treated than ziprasidone-treated patients (21.8% [N=12] versus 3.6% [N=2]). No ziprasidone-treated and one olanzapine-treated patient experienced cardiovascular-related adverse events.

Discussion

Over 6 months, both olanzapine and ziprasidone comparably controlled symptoms of schizophrenia, were generally well tolerated, and were associated with improvements in movement disorders.

From acute-study baseline to continuation-study endpoint, significantly greater mean increases in weight and body mass index were seen with olanzapine than with ziprasidone, and a higher probability of rapid weight gain was seen for olanzapine. Significant within-group median increases from baseline in fasting total cholesterol, low-density lipoprotein cholesterol, and insulin levels were also associated with olanzapine; nonsignificant changes were associated with ziprasidone. The increases in weight, glucose metabolism, and lipids associated with olanzapine during the acute study were sustained during long-term treatment.

These continuation-study results show comparable efficacy but significant tolerability differences between olanzapine and ziprasidone; these findings are consistent with results of the earlier 6-week acute study and with results from long-term efficacy, safety, and tolerability comparisons with placebo (2) and haloperidol (3). The favorable long-term tolerability results reported here for ziprasidone are consistent with results from a 6-week open-label study (4) in which switching from olanzapine to ziprasidone decreased weight, total cholesterol, and triglycerides. Notably, between-group differences in effects on total cholesterol, low-density lipoprotein cholesterol, triglycerides, and fasting insulin between study drugs in the 6-week acute study were statistically significant and favored ziprasidone but were not significant in the continuation study, perhaps owing to attrition of evaluable patients from the acute study (N=269) to continuation (N=126).

Small increases in QTc were seen in ziprasidone-treated patients, and no patient in the study had a QTc ≥500 msec. No patient experienced movement disorders.

Further investigation of the impact of antipsychotic treatment on body mass index/weight, lipid profile, and glucose metabolism is warranted to help elucidate the mechanisms underlying apparent drug-related differences.

|

|

Presented as a poster at the 155th annual meeting of the American Psychiatric Association, Philadelphia, May 19–22, 2002. Received Dec. 4, 2004; revisions received July 26 and Sept. 9, 2004; accepted Sept. 20, 2004. From the Department of Psychiatry and the Behavioral Sciences, University of Southern California; Los Angeles County and University of Southern California Medical Center, Los Angeles; State University of New York Health Sciences Center at Brooklyn, N.Y.; Clinical Trials Program, University of Florida, Gainesville; and Pfizer Inc., New York. Address correspondence and reprint requests to Dr. Simpson, Keck School of Medicine at the University of Southern California, Department of Psychiatry and the Behavioral Sciences, LAC/USC Medical Center, IRD Rm. 204, Psychiatric Outpatient Clinic, 2020 Zonal Ave., Los Angeles, CA 90033; [email protected] (e-mail). Supported by Pfizer Inc.

1. Simpson GM, Glick ID, Weiden PJ, Romano SJ, Siu CO: Randomized, controlled, double-blind multicenter comparison of the efficacy and tolerability of ziprasidone and olanzapine in acutely ill inpatients with schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder. Am J Psychiatry 2004; 161:1837–1847; correction, 2005; 162:644Google Scholar

2. Arato M, O’Connor R, Meltzer HY (ZEUS Study Group): A 1-year, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial of ziprasidone 40, 80 and 160 mg/day in chronic schizophrenia. Int Clin Psychopharmacol 2002; 17:207–215Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

3. Hirsch S, Kissling W, Bauml J, Power A, O’Connor R: A 28-week comparison of ziprasidone and haloperidol in outpatients with stable schizophrenia. J Clin Psychiatry 2002; 63:516–523Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

4. Weiden PJ, Daniel DG, Simpson G, Romano SJ: Improvement in indices of health status in outpatients with schizophrenia switched to ziprasidone. J Clin Psychopharmacol 2003; 23:595–600Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar