Risperidone Treatment of Autistic Disorder: Longer-Term Benefits and Blinded Discontinuation After 6 Months

Abstract

OBJECTIVE: Risperidone is effective for short-term treatment of aggression, temper outbursts, and self-injurious behavior in children with autism. Because these behaviors may be chronic, there is a need to establish the efficacy and safety of longer-term treatment with this agent. METHOD: The authors conducted a multisite, two-part study of risperidone in children ages 5 to 17 years with autism accompanied by severe tantrums, aggression, and/or self-injurious behavior who showed a positive response in an earlier 8-week trial. Part I consisted of 4-month open-label treatment with risperidone, starting at the established optimal dose; part II was an 8-week randomized, double-blind, placebo-substitution study of risperidone withdrawal. Primary outcome measures were the Aberrant Behavior Checklist irritability subscale and the Clinical Global Impression improvement scale. RESULTS: Part I included 63 children. The mean risperidone dose was 1.96 mg/day at entry and remained stable over 16 weeks of open treatment. The change on the Aberrant Behavior Checklist irritability subscale was small and clinically insignificant. Reasons for discontinuation of part I included loss of efficacy (N=5) and adverse effects (N=1). The subjects gained an average of 5.1 kg. Part II included 32 patients. The relapse rates were 62.5% for gradual placebo substitution and 12.5% for continued risperidone; this difference was statistically significant. CONCLUSIONS: Risperidone showed persistent efficacy and good tolerability for intermediate-length treatment of children with autism characterized by tantrums, aggression, and/or self-injurious behavior. Discontinuation after 6 months was associated with a rapid return of disruptive and aggressive behavior in most subjects.

Autistic disorder is characterized by impaired social interaction, abnormal language development, and repetitive and restricted patterns of behavior (DSM-IV), and it affects as many as 20 people per 10,000 (1, 2). Children with autism display broad differences in abilities and needs, but accompanying maladaptive behaviors such as self-injurious behavior, aggression, and tantrums are common and frequently severe enough to limit educational and developmental progress. A variety of treatments, including medication, are employed in the management of these maladaptive behaviors. Controlled trials of medication treatment of autism are limited, but evidence provides support for both conventional and atypical antipsychotic agents (3, 4). Among studies of the conventional antipsychotics, well-controlled trials of haloperidol have revealed statistically significant effects, but only modest clinical benefits, in children with autism, and short- and longer-term side effects are of concern (3, 5). Atypical antipsychotics appear to be preferred by clinicians because of the perception that atypicals have a more favorable side effect profile than typical neuroleptics, but few direct comparison data exist. Atypical agents are also of interest because of possible serotonin (5-HT) abnormalities in some individuals with autism and the high affinity of medicines such as risperidone for 5-HT receptors, especially those of the 5-HT2A and 5-HT2C classes (6). Until 2002, only one placebo-controlled study of risperidone in adults with autism (7) and a handful of open-label studies of children with pervasive developmental disorders (8) had been published. In a prior report, we described the short-term efficacy of risperidone over placebo in an 8-week controlled trial for 101 children and adolescents with autistic disorder (4). Risperidone was chosen for study given the greatest preliminary evidence for its efficacy in this population (6, 8). Although the effects of risperidone on aggression, tantrums, and self-injurious behavior were substantial in our short-term study, the question of whether these improvements would endure over time remained unanswered.

In this study, subjects who showed a positive response to risperidone in the short-term trial were enrolled in an additional 4-month open-label trial (total drug exposure=6 months), which was followed by a placebo-controlled discontinuation protocol lasting up to 8 weeks. The aim of the study was threefold: first, to determine if the short-term efficacy of risperidone is maintained over time; second, to determine if the side effect burden of risperidone remains acceptable over an extended treatment period; and third, to examine the feasibility of risperidone discontinuation after 6 months of treatment.

Method

Setting and Subjects

This study was an extension of the 8-week double-blind, placebo-controlled trial with parallel groups and the 8-week open-label risperidone treatment offered to placebo nonresponders. These short-term trials were conducted by the Autism Network of the National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH) Research Units on Pediatric Psychopharmacology between June 1999 and April 2001. The five clinical sites included the University of California at Los Angeles, Ohio State University, Indiana University, Yale University, and Kennedy Krieger Institute (Johns Hopkins University). The protocol was approved by the institutional review board at each site and the NIMH Data and Safety Monitoring Board, and written informed consent was obtained from a parent or guardian prior to enrollment. Safety and protocol fidelity were monitored through weekly conference calls involving the principal investigators and study coordinators, through quarterly reviews by the Data and Safety Monitoring Board, and through annual site visits by the coordinating center (Yale University).

This study enrolled 63 of the 101 subjects in the first protocol, all of whom met criteria for autistic disorder as defined in DSM-IV. Other entry criteria (at the time of enrollment in the initial double-blind phase) included 1) age of 5–17 years, 2) significant tantrums, aggression, self-injurious behavior, and/or agitation, 3) absence of significant medical problems and any other psychiatric disorder requiring drug therapy (e.g., bipolar disorder, psychosis), 4) weight of at least 15 kg, and 5) mental age of at least 18 months. No concomitant treatment with psychotropic medication was allowed during any phase of the study, except anticonvulsant treatment for seizure control if the child had been taking a stable dose for 4 weeks and had been free of seizures for 6 months (see reference 9 for a detailed description).

Protocol Schedule and Design

At the final visit of the initial 8-week controlled study, or the 8-week open-label risperidone treatment for placebo nonresponders, subjects deemed responders were offered enrollment in the extension protocol. Written informed consent for continued participation was obtained from the parents, and for 10 subjects deemed to have the capacity to consent, assent was obtained. The subjects were then seen every 4 weeks for 4 months for assessment of efficacy, safety, and possible need for dose adjustments. At the end of these 4 months of open-label treatment, subjects who continued to show a positive response entered the discontinuation phase. In this phase, the subjects were randomly assigned again, this time either to continued risperidone at the same dose or to gradual placebo substitution, in a double-blind fashion. The discontinuation reduced the maintenance dose by 25% per week. Thus, the dose was 75% of the week 16 dose for 1 week, followed by 50% of the week 16 dose for the second week, 25% of the week 16 dose for the third week, and placebo only by the fourth week. All subjects were seen weekly for a total of 8 weeks in the discontinuation phase.

Baseline Assessment and Measurement of Outcome

At screening for participation in the initial 8-week treatment study, autistic disorder was ascertained through a history and examination by a research team and was corroborated by the Autism Diagnostic Interview—Revised (10), administered by a clinician trained to reliability (11). The screening measures also included intelligence testing, the Vineland Adaptive Behavior Scales (12, 13), routine laboratory tests, an electrocardiogram, measurements of height, weight, and vital signs, a medical history, and a physical examination. All subjects were also required to manifest clinically significant problems consisting of aggression, tantrums, and/or self-injury as defined by a score of 18 or higher on the irritability subscale of the Aberrant Behavior Checklist—Community version (14, 15) rated by the parent (or primary caretaker) and confirmed by clinician review. Scores on this 15-item subscale range from 0 to 45, with higher scores indicating greater pathology. In addition, the subjects were required to receive a score of moderate or higher on the Clinical Global Impression (GCI) severity scale (16, pp. 218–222) from the examining clinician.

Eligible subjects were randomly assigned to receive risperidone or placebo for 8 weeks; details are provided elsewhere (4). The primary outcome measures were the parent-rated irritability subscale of the Aberrant Behavior Checklist and the clinician-rated CGI improvement scale. Subjects showing a 25% reduction on the irritability subscale and a rating of much improved or very much improved on the CGI improvement scale by the blinded clinical evaluator were classified as positive responders and were eligible for the 4-month open-label extension phase. At the end of the 4-month extension, responders were eligible for the randomized discontinuation phase. In the discontinuation phase, relapse was defined as a 25% increase in the score on the parent-rated Aberrant Behavior Checklist irritability subscale and a CGI improvement rating of much worse or very much worse, compared to the prediscontinuation baseline, for at least 2 consecutive weeks, as assessed by a blinded clinician.

Secondary parent-rated outcome measures included the four additional subscales of the Aberrant Behavior Checklist: lethargy/social withdrawal, stereotypic behavior, hyperactivity, and inappropriate speech. At baseline, the parents were interviewed to identify the child’s target symptoms and to rate compulsive behaviors on the Children’s Yale-Brown Obsessive Compulsive Scale (see references 4, 13, and 17 for details on study assessment).

Medication Dosing

The medication schedule in the initial 8-week trial was based on the child’s weight and clinical response. The maximum risperidone dose was 2.5 mg/day for children between 15 and 45 kg and 3.5 mg/day for children weighing above 45 kg. Dose reductions to manage side effects were allowed at any time. During the 4-month open phase, clinicians were allowed to adjust the total daily dose according to response and/or adverse events, with the total daily dose increased up to a maximum of 3.5 mg/day for children weighing 15–45 kg and up to 4.5 mg/day for children above 45 kg.

Safety Monitoring

The routine laboratory tests, electrocardiogram, and physical examination were repeated at entry into the extension phase and prior to the discontinuation. Weight and vital signs were assessed at each visit. At each visit, the primary clinician asked the parents about the child’s health complaints, intercurrent illness, and concomitant medications, and the clinician administered a 32-item checklist concerning the child’s energy level, muscle stiffness, motor restlessness, bowel and bladder habits, sleep, and appetite. Neurological side effects were further assessed at each visit with the Simpson-Angus Rating Scale (18) and the Abnormal Involuntary Movements Scale (AIMS) (16, pp. 534–537). Adverse events indicated by any of these methods were documented according to severity, duration, attribution, outcome, and action taken.

Statistical Analysis

Open-label trial

The statistical tests were two-tailed with alpha set at 0.05. To evaluate differences between subjects who participated in the extension trial and those who did not, we compared demographic and clinical characteristics by t tests for continuous variables and chi-square tests for categorical variables. All subjects who enrolled in the extension trial were included in an intent-to-treat analysis. The monthly scores on the parent-rated subscales (irritability, lethargy, stereotypy, hyperactivity, and inappropriate speech) of the Aberrant Behavior Checklist were analyzed with mixed effects linear regression models in which time, site, and site-by-time interaction were the fixed effects (19). The average slope of the regression line (change in irritability score or score on other subscale) was calculated for each individual across time. In addition, the distribution of CGI improvement scores was calculated across time.

Discontinuation phase

As originally planned in the protocol, interim analyses were performed for the Data and Safety Monitoring Board after the first 16 and 32 subjects completed this phase of the study (9). These interim analyses were reviewed only by the Data and Safety Monitoring Board, independently of the study investigators. Chi-square analysis with Yates’s correction was used to compare the rates of relapse in the two groups. To evaluate the time to relapse and the probability of relapse, the log rank survival analysis of continued drug versus placebo and the Kaplan-Meier procedure were used.

Results

Baseline Characteristics

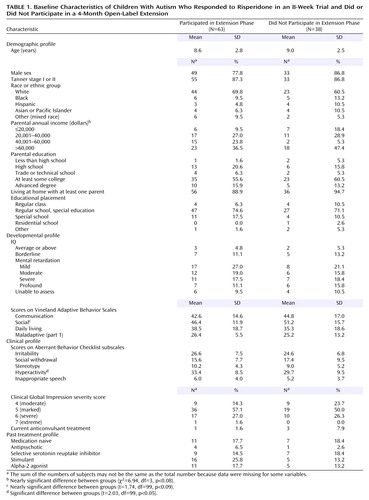

Of the original 101 subjects (82 boys and 19 girls) enrolled in the short-term trial, 63 subjects (mean age=8.6 years, SD=2.8) showed a positive response to risperidone and consented to participate in the extension protocol. Of these 63 subjects, 30 were classified as responders during the double-blind trial and 30 were so classified in the 8-week open-label risperidone trial for placebo nonresponders. There were no differences in scores on the irritability subscale of the Aberrant Behavior Checklist or in the distribution of CGI severity scores at the baseline of the extension phase between subjects who entered directly from the double-blind study and those who entered from the 8-week open-label trial for placebo nonresponders. Therefore, the two groups were combined in the efficacy analysis. During the data analysis, three subjects were noted to have entered the extension phase without fully meeting the response criteria. Inclusion of these three subjects did not alter the results, and thus they were included in all analyses. Demographic characteristics of the entire 63 subjects in the extension study are shown in Table 1. When compared to the 38 subjects who did not participate in the extension phase, the extension group showed few differences. Of a total of 24 comparisons, only one variable, the baseline score on the Aberrant Behavior Checklist hyperactivity subscale, differed significantly, being slightly higher at baseline in the subjects continuing in the extension study.

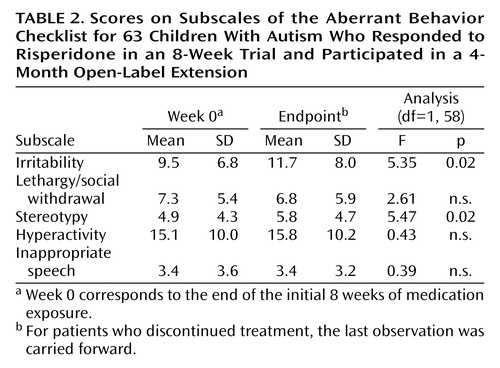

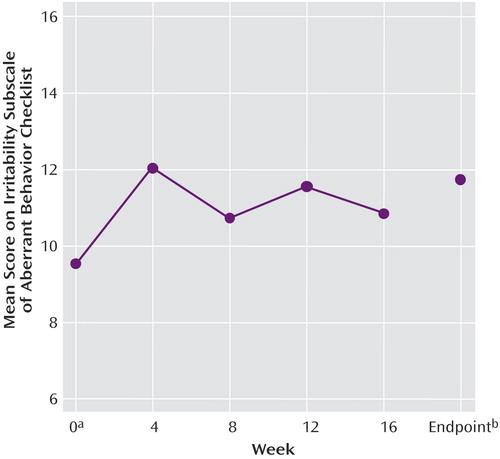

4-Month Open-Label Treatment: Outcomes

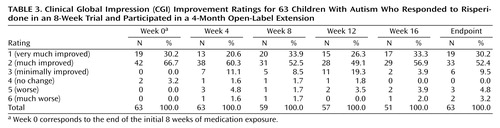

A total of 51 subjects (81.0%) completed the 16-week open-label treatment period. Of the 12 dropouts from the extension study, five subjects were withdrawn because of loss of efficacy, one was withdrawn because of noncompliance with the protocol, one withdrew because of an adverse event (constipation), one withdrew consent (no longer interested in medication treatment), and four were lost to follow-up. The mixed effects regression model for all 63 subjects in the intent-to-treat analysis revealed a significant time effect for the irritability subscale of the Aberrant Behavior Checklist (Table 2, Figure 1). However, the mean irritability ratings showed only a minor increase across the 16-week extension phase, from a mean score of 9.5 (SD=6.8) at the start to 10.8 (SD=7.1) at week 16 (Figure 1), in contrast to the mean pretreatment irritability score of 26.6 (SD=7). This 1-point increase lacks clinical significance. Indeed, after 16 weeks of treatment the mean score still showed a 59% reduction from the mean rating at the initiation of risperidone treatment 6 months before, a percent reduction identical to that seen after the initial 8-week double-blind study and yielding an effect size of d>1.0. Analysis of the CGI improvement ratings at endpoint showed that 82.5% of the subjects (N=52) continued to be rated as much improved or very much improved (1 or 2 on the CGI improvement scale) (Table 3). By contrast, only 7.9% were rated as worse or much worse compared to baseline.

The risperidone doses were also examined to determine whether a dose increase is required to ensure stability of treatment effects. The mean risperidone doses were 1.96, 1.80, 1.87, 2.10, and 2.08 mg/day for weeks 0, 4, 8, 12, and 16, respectively, representing a modest 6% increase over the 4-month treatment period.

Secondary outcome measures included the other subscales of the Aberrant Behavior Checklist. Table 2 shows scores on those subscales and results of the random regression model.

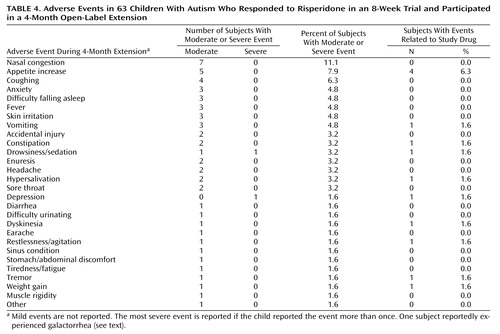

4-Month Open-Label Treatment: Adverse Events

Adverse events, especially mild to moderate increased appetite, tiredness, and/or drowsiness, were common (Table 4). Only one subject withdrew because of an adverse event (constipation). Although the parents of six subjects (9.5%) reported “abnormal movements,” no dyskinesias were identified on repeated examination with the AIMS and Simpson-Angus scale by a physician. One subject with preexisting obesity had galactorrhea according to the mother’s report, but this was not observed on examination. Compared to their weight at the initiation of risperidone treatment, the subjects showed a 6-month weight increase of 5.1 kg (SD=3.6) (paired t=7.46, df=31, p<0.001), which was significantly greater (p<0.001) than the amount expected on the basis of available developmental norms. This finding has been reviewed in more detail in a separate report (20).

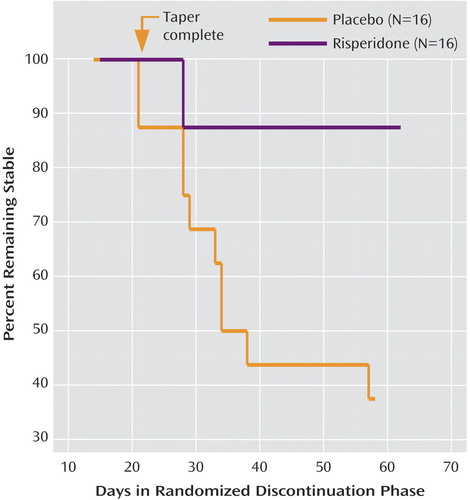

Discontinuation Phase

A total of 38 subjects were enrolled in the discontinuation phase. Few differences in baseline characteristics were observed between the subjects in the discontinuation phase and the remainder of the 63 subjects, aside from the discontinuation subjects’ again showing higher mean baseline scores on the Aberrant Behavior Checklist hyperactivity factor (mean=34.4, SD=8.7, versus mean=30.6, SD=9.0; t=2.08, df=99, p=0.04). Also, subjects in the discontinuation phase showed higher mean baseline scores on the Aberrant Behavior Checklist irritability factor than the remaining 63 subjects (mean=27.6, SD=6.1, versus mean 24.8, SD=7.7, t=2.02, df=99, p=0.05). As planned, the NIMH Data and Safety Monitoring Board independently reviewed two interim efficacy analyses, first after the initial 16 subjects completed this phase and again after the first 32 subjects finished. The relapse rate after 32 subjects completed this phase was significantly higher in the placebo-treated group (62.5%, N=10) than in the group receiving continued risperidone (12.5%, N=2) (Yates’s corrected χ2=6.53, df=1, p=0.01). The median survival time, i.e., time to relapse, was 34 days for the placebo-treated subjects versus 57 days for those continuing to take risperidone (Figure 2). On the basis of the results of this planned interim analysis, the NIMH Data and Safety Monitoring Board ruled that the discontinuation phase be stopped immediately. The four subjects who were still in this phase of the protocol exited the study and were treated clinically. Exploratory post hoc analyses were performed in an effort to identify any clinical predictors of relapse. Age, initial Aberrant Behavior Checklist irritability score, and IQ all failed to differ significantly (p>0.30) between the relapsing and nonrelapsing subjects.

Discussion

Data from this study suggest that risperidone is a well-tolerated and effective treatment for up to 6 months for children with autism complicated by tantrums, aggression, and self-injury. As measured by the primary indices of response, the CGI improvement scale and the Aberrant Behavior Checklist irritability subscale, improvements associated with risperidone administration were maintained in over 80% of the subjects, with very good tolerability. Furthermore, gradual substitution of placebo for risperidone was associated with a greater return of aggression, temper outbursts, and self-injurious behavior than in the subjects who continued to receive risperidone in the discontinuation phase. Taken together, these data strongly suggest that risperidone is an efficacious treatment for short- and intermediate-term management of serious behavioral problems in children with autism.

As in our study of short-term risperidone efficacy (4), risperidone was also associated with continued maintenance of improvements on the Aberrant Behavior Checklist subscales for hyperactivity, stereotypic behavior, and lethargy/social withdrawal. In addition, the mean reduction from baseline in the irritability subscale scores of 59% at the last observation in the extension phase was nearly identical to that observed in the risperidone group at the completion of the 8-week double-blind efficacy trial.

These data expand the limited published database on extended treatment of autistic disorder with medication. Heretofore, the largest extended study of neuroleptic treatment for autistic disorder was the examination of the effects of haloperidol over a 6-month period. In that study (5), 60 children treated with a mean dose of 1.23 mg/day of haloperidol were classified as “good responders.” After 6 months of treatment, 33 (63%) of 52 subjects were rated as “much improved.” Autism factor ratings derived from the Children’s Psychiatric Rating Scale obtained on entry and at 6 months showed an average decline of 23% from baseline. Upon abrupt withdrawal of haloperidol, only 14% of the children were rated as much worse and 50% showed at least mild deterioration.

In an open-label prospective study of risperidone for 11 children with autistic disorder, Zuddas et al. (21) noted that 10 of the 11 showed enduring improvement over the 12-month observation period. Another open trial (22) of risperidone enrolled 22 subjects with autistic disorder. Of these, 15 subjects showed significant improvement at a mean dose of 1.2 mg/day for up to 7 months of treatment. Additional published observations include positive responses maintained over a 4-month period in responders (23) and improvement maintained during a 2-year treatment history in two adults with autistic disorder (24). It should be noted that few earlier studies defined specific entry criteria for aggression or disruptive behavior, but, taken together, the available accounts suggest that risperidone’s benefit for aggression, severe tantrums, and self-injury accompanying autistic disorder persisted over these intermediate treatment periods (6–12 months), although additional long-term treatment data focusing on managing severe and challenging behaviors are clearly needed.

A key clinical question concerns the length of continued treatment with risperidone for this clinical indication. On one hand, the return of aggression, tantrums, and agitation was five times as great in the placebo-substitution group as in the subjects who continued to take risperidone. On the other hand, 37.5% (six of 16) of the children in the placebo-substitution group did not relapse during the 2-month discontinuation period, demonstrating some degree of variability in outcome. It is conceivable that more gradual drug tapering may have moderated the observed relapse in the risperidone group or that dose reduction, rather than complete medication discontinuation, may have been sufficient to maintain treatment gains. It is also conceivable that concomitant behavioral treatment reinforcing replacement behaviors could protect against relapse following risperidone withdrawal. Nevertheless, the high rate of relapse observed in our study suggests caution when withdrawal of effective treatment for these target symptoms is considered. At a minimum, clinicians should document a clear period of stable functioning before initiating medication taper (25) and ensure that appropriate psychosocial supports are in place to minimize relapse risk. No factors predicting relapse were identifiable given the modest number of subjects in the discontinuation phase of this study, but they certainly form an important future research question. Longer-term follow-up information on outcome may help clinicians make decisions about maintenance treatment. To this end, we are in the process of obtaining 18-month safety data for our study group.

Although adverse events associated with risperidone exposure were observed to be common in this study, most were not deemed clinically significant, and many were not attributed to risperidone. It is important that only one subject withdrew from the 4-month open-label treatment because of an adverse event, and no cases of dyskinesia were observed during 6 months of treatment or upon withdrawal. The absence of dyskinesia in this study is noteworthy given the report by Campbell and colleagues (26) that 30% of 118 subjects showed dyskinesia following withdrawal of haloperidol after a similar duration of treatment, although the more gradual taper used in this study may be responsible for the finding. Weight gain associated with treatment was significant and in some, but not all, cases posed a concern (20), especially since antipsychotic-related weight gain has been associated with diabetes and other adverse outcomes. Longer-term observations to determine the clinical significance of weight gain as well as other adverse events are needed to evaluate the risk-benefit ratio for risperidone treatment in children with autistic disorder.

There were several limitations in this investigation. First, although the data collection period in this phase of the study spanned up to a maximum total of 8 months of risperidone exposure, this does not completely mimic clinical practice, as many patients receive treatments like risperidone for longer time periods. Also, there was no systematic effort to reduce or constrain individual daily doses over time, leaving some uncertainty about the lowest possible long-term dose. This limitation notwithstanding, the relatively low mean dose (approximately 2.0 mg/day) of risperidone used in this study was effective in managing the specific target symptoms of aggression, agitation, and self-injury. This mean dose was remarkably similar to the doses in several other studies (16, 22, 27, 28). The possibility of solidifying these gains or even extending the benefit of risperidone treatment by combining it with behavior therapy was not explored in this investigation but is an important research question for future studies. Finally, the safety observations of the study were limited to a maximum of 8 months of risperidone exposure in a relatively small study group. Thus, our data may be insufficient to estimate precisely the long-term risks of risperidone in children.

In summary, intermediate-length treatment with risperidone appeared to be associated with the maintenance of reductions in aggression, agitation, self-injury, and irritability from short-term treatment. There was little evidence of accommodation to the effects of risperidone, and the medication appeared to be well tolerated in a group of children and adolescents with autistic disorder. Additional studies on predictors of stable improvement, longer-term safety, and approaches combining other interventions are of interest.

Acknowledgments

The following are the authors of this report listed by role and study site: Ohio State University, principal investigator Michael G. Aman, Ph.D., co-investigators L. Eugene Arnold, M.Ed., M.D., Ronald Lindsay, M.D., Patricia Nash, M.D., Jill Hollway, B.A.; University of California at Los Angeles, principal investigator James T. McCracken, M.D., co-investigators Bhavik Shah, M.D., James McGough, M.D., Pegeen Cronin, Ph.D., Lisa Lee, B.A.; Indiana University, principal investigator Christopher J. McDougle, M.D., co-investigators David Posey, M.D., Naomi Swiezy, Ph.D., Arlene Kohn, B.A.; Yale University, principal investigator, Lawrence Scahill, M.S.N., Ph.D., co-investigators Andres Martin, M.D., Kathleen Koenig, M.S.N., Fred Volkmar, M.D., Deirdre Carroll, M.S.N., Allison Lancor, B.S.; Kennedy Krieger Institute, principal investigator Elaine Tierney, M.D., co-investigators Jaswinder Ghuman, M.D., Nilda Gonzalez, M.D., Marco Grados, M.D.; National Institute of Mental Health, principal investigator Benedetto Vitiello, M.D., co-investigator Louise Ritz, M.B.A.; Columbia University, statistician Mark Davies, M.P.H.; Nathan Kline Institute, data management James Robinson, M.Ed., Don McMahon, M.S.

|

|

|

|

Received Oct. 23, 2003; revision received Sept. 22, 2004; accepted Oct. 1, 2004. From the Research Units on Pediatric Psychopharmacology Autism Network (individual contribuors are listed in Acknowledgments). Address correspondence and reprint requests to Dr. McCracken, UCLA Neuropsychiatric Institute, 760 Westwood Plaza, Los Angeles, CA 90024-1759; [email protected] (e-mail). Supported by NIMH contracts N01 MH-70010 (principal investigator: Dr. McCracken), N01 MH-70009 (principal investigator: Dr. Scahill), N01 MH-70001 (principal investigator: Dr. McDougle), and N01 MH-80011 (principal investigator: Dr. Aman); by NIH Division of Research Resources General Clinical Research Center grants M01 RR-00750 (to Indiana University), M01 RR-00052 (to Johns Hopkins University), M01 RR-00034 (to Ohio State University), and M01 RR-06022 (to Yale University); by NIMH grant MH-01805 (to Dr. McCracken); and by funding from the Korczak Foundation (to Dr. Scahill). Study medications were donated by Janssen Pharmaceutica. The authors thank the following members of the Autism Network of the NIMH Research Units on Pediatric Psychopharmacology Scientific Advisory Board: C.T. Gordon, M.D., Joseph DeVeaugh-Geiss, M.D., Henrietta Leonard, M.D., Richard Shader, M.D., and Susan Swedo, M.D., for their contributions; the NIMH Data and Safety Monitoring Board and Phillip Walson, M.D., for their comments and guidance; and Erin Kustan and Caifeng Fu for assistance in preparing this report.The content of this publication does not necessarily reflect the views or policies of the Department of Health and Human Services, nor does mention of trade names, commercial products, or organizations imply endorsement by the U.S. government.

Figure 1. Scores on the Irritability Subscale of the Aberrant Behavior Checklist for 63 Children With Autism Who Responded to Risperidone in an 8-Week Trial and Participated in a 4-Month Open-Label Extension

aWeek 0 corresponds to the end of the initial 8 weeks of medication exposure.

bFor patients who discontinued treatment, the last observation was carried forward.

Figure 2. Survival Analysis for Children With Autism Who Responded to Risperidone and Were Then Randomly Assigned to Placebo or Continued Risperidone for 8 Weeksa

aFor the placebo group, the risperidone dose was decreased by 25% per week. Relapse was defined as a 25% increase in the score on the Aberrant Behavior Checklist irritability subscale and a CGI improvement rating of much worse or very much worse, compared to the prediscontinuation baseline, for at least 2 consecutive weeks. The difference between groups was significant (test for equality of survival distributions for treatment, log rank=6.89, df=1, p=0.009).

1. Chakrabarti S, Fombonne E: Pervasive developmental disorders in preschool children. JAMA 2001; 285:3093–3099Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

2. Rutter M, Silberg J, O’Connor T, Simonoff E: Genetics and child psychiatry, II: empirical research findings. J Child Psychiatry 1999; 40:19–55Crossref, Google Scholar

3. Anderson LT, Campbell M, Adams P, Small AM, Perry R, Shell J: The effects of haloperidol on discrimination learning and behavioral symptoms in autistic children. J Autism Dev Disord 1989; 19:227–239Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

4. McCracken JT, McGough J, Shah B, Cronin P, Hong D, Aman MG, Arnold LE, Lindsay R, Nash P, Hollway J, McDougle CJ, Posey D, Swiezy N, Kohn A, Scahill L, Martin A, Koenig K, Volkmar F, Carroll D, Lancor A, Tierney E, Ghuman J, Gonzalez NM, Grados M, Vitiello B, Ritz L, Davies M, Robinson J, McMahon D (Research Units on Pediatric Psychopharmacology Autism Network): a double-blind, placebo-controlled trial of risperidone in children with autistic disorder. N Engl J Med 2002; 347:314–321Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

5. Perry R, Campbell M, Adams P, Lynch N, Spencer EK, Curren EL, Overall JE: Long-term efficacy of haloperidol in autistic children: continuous versus discontinuous drug administration. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 1989; 28:87–92Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

6. McDougle CJ, Scahill L, McCracken JT, Aman MG, Tierney E, Arnold LE, Freeman BJ, Martin A, McGough JJ, Cronin P, Posey DJ, Riddle MA, Ritz L, Swiezy NB, Vitiello B, Volkmar FR, Votolato NA, Walson P: Research Units on Pediatric Psychopharmacology (RUPP) Autism Network: background and rationale for an initial controlled study of risperidone. Child Adolesc Psychiatr Clin N Am 2000; 9:201–224Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

7. McDougle CJ, Holmes JP, Carlson DC, Pelton GH, Cohen DJ, Price LH: A double-blind, placebo-controlled study of risperidone in adults with autistic disorder and other pervasive developmental disorders. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1998; 55:633–641Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

8. Fisman S, Steele M: Use of risperidone in pervasive developmental disorders: a case series. J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol 1996; 6:177–190Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

9. Scahill L, McCracken J, McDougle CJ, Aman M, Arnold LE, Tierney E, Cronin P, Davies M, Ghuman J, Gonzalez N, Koenig K, Lindsay R, Martin A, McGough J, Posey DJ, Swiezy N, Volkmar F, Ritz L, Vitiello B: Methodological issues in designing a multisite trial of risperidone in children and adolescents with autism. J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol 2001; 11:377–388Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

10. Lord C, Rutter M, Le Couteur A: Autism Diagnostic Interview—Revised: a revised version of a diagnostic interview for caregivers of individuals with possible pervasive developmental disorders. J Autism Dev Disord 1994; 24:659–685Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

11. Lord C, Pickles A, McLennan J, Rutter M, Bregman J, Folstein S, Fombonne E, Leboyer M, Minshew N: Diagnosing autism: analyses of data from the Autism Diagnostic Interview. J Autism Dev Disord 1997; 27:501–517Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

12. Carter AS, Volkmar FR, Sparrow SS, Wang JJ, Lord C, Dawson G, Fombonne E, Loveland K, Mesibov G, Schopler E: The Vineland Adaptive Behavior Scales: supplementary norms for individuals with autism. J Autism Dev Disord 1998; 28:287–302Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

13. Arnold LE, Aman MG, Martin A, Collier-Crespin A, Vitiello B, Tierney E, Asarnow R, Bell-Bradshaw F, Freeman BJ, Gates-Ulanet P, Klin A, McCracken JT, McDougle CJ, McGough JJ, Posey DJ, Scahill L, Swiezy NB, Ritz L, Volkmar F: Assessment in multisite randomized clinical trials of patients with autistic disorder: the Autism RUPP [Research Units on Pediatric Psychopharmacology] Network. J Autism Dev Disord 2000; 30:99–111Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

14. Aman MG, Singh NN: Aberrant Behavior Checklist—Community: Supplementary Manual. East Aurora, NY, Slosson Educational Publications, 1994Google Scholar

15. Brown EC, Aman MG, Havercamp SM: Factor analysis and norms for parent ratings on the Aberrant Behavior Checklist—Community for young people in special education. Res Dev Disabil 2002; 23:45–60Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

16. Guy W (ed): ECDEU Assessment Manual for Psychopharmacology: Publication ADM 76–338. Washington, DC, US Department of Health, Education, and Welfare, 1976Google Scholar

17. Arnold LE, Vitiello B, McDougle C, Scahill L, Shah B, Gonzalez NM, Chuang S, Davies M, Hollway J, Aman MG, Cronin P, Koenig K, Kohn AE, McMahon DJ, Tierney E: Parent-defined target symptoms respond to risperidone in RUPP Autism Network Study: a customer approach to clinical trials. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 2003; 42:1443–1450Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

18. Simpson GM, Angus JWS: A rating scale for extrapyramidal side effects. Acta Psychiatr Scand Suppl 1970; 212:11–19Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

19. Gibbons RD, Hedeker D, Elkin I, Waternaux C, Kraemer HC, Greenhouse JB, Shea MT, Imber SD, Sotsky SM, Watkins JT: Some conceptual and statistical issues in analysis of longitudinal psychiatric data: application to the NIMH Treatment of Depression Collaborative Research Program dataset. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1993; 50:739–750Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

20. Martin A, Scahill L, Anderson GM, Aman M, Arnold LE, McCracken J, McDougle CJ, Tierney E, Chuang S, Vitiello B, Research Units on Pediatric Psychopharmacology Autism Network: Weight and leptin changes among risperidone-treated youths with autism: 6-month prospective data. Am J Psychiatry 2004; 161:1125–1127Link, Google Scholar

21. Zuddas A, Di Martino A, Muglia P, Cichetti C: Long-term risperidone for pervasive developmental disorder: efficacy, tolerability, and discontinuation. J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol 2000; 10:79–90Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

22. Malone RP, Maislin G, Choudhury MS, Gifford C, Delaney MA: Risperidone treatment in children and adolescents with autism: short- and long-term safety and effectiveness. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 2002; 41:140–147Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

23. Masi G, Cosenza A, Mucci M, Brovedani P: Open trial of risperidone in 24 young children with pervasive developmental disorders. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 2001; 40:1206–1214Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

24. Dartnall NA, Holmes JP, Morgan SN, McDougle CJ: Brief report: two-year control of behavioral symptoms with risperidone in two profoundly retarded adults with autism. J Autism Dev Disord 1999; 29:87–91Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

25. Pappadopulos E, Macintyre JC, Crismon ML, Findling RL, Malone RP, Derivan A, Schooler N, Sikich L, Greenhill L, Schur SB, Felton CJ, Kranzler H, Rube DM, Sverd J, Finnerty M, Ketner S, Siennick SE, Jensen PS: Treatment recommendations for the use of antipsychotics for aggressive youth (TRAAY), part II. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 2003; 42:145–161Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

26. Campbell M, Armenteros JL, Malone RP, Adams PB, Eisenberg ZW, Overall JE: Neuroleptic-related dyskinesias in autistic children: a prospective, longitudinal study. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 1997; 36:835–843Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

27. Findling RL, Maxwell K, Wiznitzer M: An open clinical trial of risperidone monotherapy in young children with autistic disorder. Psychopharmacol Bull 1997; 33:155–159Medline, Google Scholar

28. Buitelaar JK, van der Gaag RJ, Cohen-Kettenis P, Melman CT: A randomized controlled trial of risperidone in the treatment of aggression in hospitalized adolescents with subaverage cognitive abilities. J Clin Psychiatry 2001; 62:239–248Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar