Impact of Referral Source and Study Applicants’ Preference for Randomly Assigned Service on Research Enrollment, Service Engagement, and Evaluative Outcomes

Abstract

OBJECTIVE: The inability to blind research participants to their experimental conditions is the Achilles’ heel of mental health services research. When one experimental condition receives more disappointed participants, or more satisfied participants, research findings can be biased in spite of random assignment. The authors explored the potential for research participants’ preference for one experimental program over another to compromise the generalizability and validity of randomized controlled service evaluations as well as cross-study comparisons. METHOD: Three Cox regression analyses measured the impact of applicants’ service assignment preference on research project enrollment, engagement in assigned services, and a service-related outcome, competitive employment. RESULTS: A stated service preference, referral by an agency with a low level of continuity in outpatient care, and willingness to switch from current services were significant positive predictors of research enrollment. Match to service assignment preference was a significant positive predictor of service engagement, and mismatch to assignment preference was a significant negative predictor of both service engagement and employment outcome. CONCLUSIONS: Referral source type and service assignment preference should be routinely measured and statistically controlled for in all studies of mental health service effectiveness to provide a sound empirical base for evidence-based practice.

Participants in research on mental health services are rarely blind to their experimental assignments, and so attrition caused by disappointment in service assignment is a well-recognized risk. Researchers can minimize overall attrition, as well as the threat of differential attrition (1), by screening out applicants with a priori service preferences. However, some applicants may choose not to disclose their preference to ensure that they have a chance to be assigned to a favored program, or they may feel they do not have a personal preference over and above the obvious one posed by the study design. For instance, when the experimental comparison is between a new intervention and services as usual, many applicants may prefer the new program even before they learn much about it.

Unfortunately, random assignment will not always equalize preexisting study enrollee characteristics across experimental groups (2), and this will always be the case when study enrollees tend to prefer one service condition over another. Common sense tells us that service assignment preference must first be balanced within the total enrollee group for it to be distributed equitably across experimental conditions. For example, if 60% of enrollees have a preference for condition A and 40% have a preference for condition B, then, with true equivalence across conditions, service A would have 60% pleased and 40% disappointed assignees, while service B would have 40% pleased and 60% disappointed assignees. To the extent that participant satisfaction or disappointment influences service engagement and study outcomes (3, 4), research findings will be biased in spite of random assignment (5–7).

Previous experience with mental health services may influence applicants’ attitudes toward research participation and the experimental services offered by a study (8, 9). Applicants referred by agencies not designed to provide continuity in outpatient care (e.g., homeless shelters, emergency units) are typically more receptive to a study offering any type of continuous care than are applicants referred by mental health centers (10, 11). On the other hand, study applicants already engaged in outpatient services should be more likely to have a service preference. If a research study enrollee is assigned to a control condition that appears to be no better than previously received services, the enrollee may enter into the assigned program halfheartedly or refuse services altogether (1, 12). Likewise, if study enrollees have to relinquish a current service to participate in an experimental program, they may delay contacting the assigned program or withdraw from project participation (13, 14).

The present study investigates the impact of preference in experimental condition assignment on study applicants’ motivation to enroll in a mental health services research project, engage in assigned services, and pursue the project’s targeted outcomes.

Method

Data were taken from the Massachusetts Employment Intervention Project, which was funded from 1995 to 2000 through the Employment Intervention Demonstration Program of the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (15).

Experimental Programs

Program of assertive community treatment (PACT) model

PACT (16, 17) is a mobile treatment team that provides a variety of mental health and medical services (18). The program in Worcester, Mass., was created by Leonard Stein, M.D., and Jana Frey, Ph.D., of Madison, Wis., in 1996. Fidelity was verified through annual site visits by Gary Bond, Ph.D., and Dr. Frey. Following the recommended 1:10 staff-to-consumer ratio, the ceiling on PACT enrollment was 90 participants, with an enrollment rate of five to seven participants per month.

Clubhouse model

A clubhouse (19) is a facility-based day program offering membership in a supportive community. A defining aspect is the 9–5 “work-ordered day” in which members and staff work side by side to perform voluntary work essential to the clubhouse (20). Genesis Club, Inc., in Worcester, which had an average annual enrollment of 400 members, was certified by the International Center for Clubhouse Development as having full compliance with the Standards for Clubhouse Programs (21).

Study Group

Individuals were eligible for the study if they resided in the vicinity of Worcester, were 18 years old or older, did not have severe retardation (IQ greater than 60), were currently unemployed, and were given a primary DSM-IV diagnosis of a schizophrenia spectrum disorder, major depression, or bipolar disorder. Diagnostic information was obtained through medical records. When there was no clear diagnosis, eligibility was confirmed by DSM-IV diagnostic assessments (22) conducted by psychiatric residents at the University of Massachusetts Medical School.

Recruitment was from February 1996 through May 1998. Presentations were made at local agencies and advocacy groups, and self-referrals were elicited through flyers, radio, and newspapers. Recruiters explained that study enrollees would be expected to slowly relinquish their current clinical services if assigned to PACT, or to relinquish any current day program if assigned to the clubhouse. During intake sessions, interviewers read a description of the study aloud, explained randomization, and asked each applicant if he or she would be willing to participate fully in either experimental program regardless of personal preference. Applicants who expressed understanding and agreed to participate provided written informed consent.

Measures of Service Assignment Preference

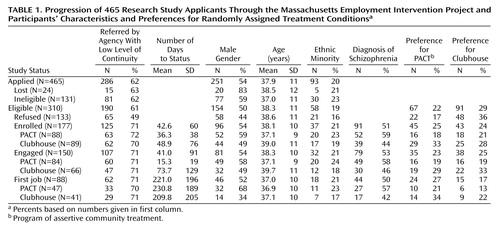

As Table 1 shows, one-half (51% [N=158]) of the 310 eligible applicants expressed a preference for being randomly assigned to one of the two experimental programs. Program recruiters recorded these preferences, and reasons for having a preference, verbatim. Assignment preferences were content-coded as pro-PACT, pro-clubhouse, and no expressed preference and then recoded after random assignment as match to preference, mismatch to preference, or no preference. Reluctance to relinquish existing services was dichotomized as reluctant to exchange current day program for clubhouse versus reluctant to exchange current clinical services for PACT.

Measure of Type of Referral Source

Applications were received from 42 local organizations, as well as through self-referrals and family referrals. Following previous research (10, 23), we dichotomized referral sources (or key provider agencies for self-referrals or family referrals) as having either a high level of continuity in outpatient care (routine treatment by clinicians, day programs, or case managers) or a low level of continuity in outpatient care (inpatient, emergency, and screening units of hospitals, shelters, residential treatment centers, nursing homes, or jails). As Table 1 shows, approximately 60% of both eligible and ineligible applicants were recruited from sources characterized as having a low level of continuity of care.

Type of referral source was unrelated to specific preference for PACT or clubhouse assignment, but enrollees from agencies with a high level of continuity of care were more likely than enrollees from agencies with a low level to have a service assignment preference (62% [N=32] versus 45% [N=56]) (χ2=3.93, df=1, p<0.05).

Statistical Analyses

Three survival (event history) analyses (24) were conducted to test the impact of recruitment variables on length of time to study enrollment, time to service engagement, and time to first competitive job. Survival analysis tracks the timing of specific events in relation to the participant’s date of study entry, regardless of individual length of observation period. SPSS version 11.0 (SPSS, Inc., Chicago) was used for all data analyses.

Time to study enrollment was measured as calendar days from application to date of random assignment to service. Period of observation was from application to the end of the recruitment period, which was comparable for enrolled (mean=462 days) and nonenrolled (mean=426 days) applicants. One applicant who took 18 months to enroll was dropped from the analysis as an extreme outlier. Applications received later in the recruitment process were processed more rapidly and, hence, were more likely to result in enrollment. Therefore, timing of application and timing of enrollment were correlated (r=–0.40, p<0.001), violating the assumption of stability of the dependent measure in respect to absolute time. For this reason, life tables were not constructed for this analysis of project enrollment, but timing of application was included as a control variable in the Cox regression.

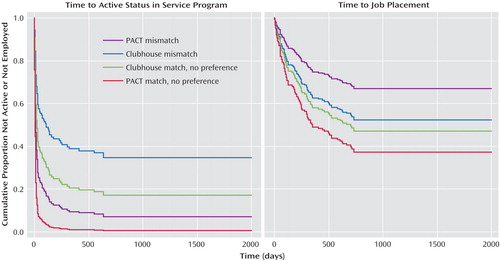

Time to program engagement was measured as calendar days from enrollment to the first day of the first period of active status in the assigned experimental program, which for censored (never-engaged) participants was coded as days from enrollment to end of the follow-up period (Dec. 31, 2000). Two clubhouse enrollees who died before service contact were omitted from this analysis, along with one PACT enrollee who refused use of his data. Active status was operationally defined, in keeping with program and regional reporting formulas and published definitions of service continuity (25), as any temporal period with at least 3 days of direct service contact in which contact averaged at least 1 hour per month and no gap in service exceeded 90 days. Match to preference and mismatch to preference were entered as dummy covariates, with no preference as the reference category. In the unadjusted life table in Figure 1, match to preference and no preference were combined as the reference category for mismatch to preference.

Time to first job was measured as calendar days from enrollment to the first day of the participant’s first competitive job (any job located in a mainstream, integrated setting paying at least minimum wage and lasting more than 5 days). Time to first job for censored (never-employed) participants was coded as days from enrollment to the participant’s 24-month anniversary date, the follow-up timeframe adopted by the larger multisite-supported Employment Intervention Demonstration Program. Omitted from the analysis were five enrollees who died during the 24-month observation period, the PACT participant who refused use of his data, and another PACT participant who was a crossover to the clubhouse. As with time to program engagement, match to preference and no preference were combined as the reference category for mismatch to preference in the life table.

Results

Predictors of Research Study Enrollment

Table 1 presents an overview of participants’ progression through the research study. Study applicants who were ineligible or lost to follow-up (N=155) were more likely than eligible applicants (N=310) to be male (63% versus 50%) (χ2=6.93, df=1, p<0.01). Otherwise, status in the project was unrelated to demographic variables.

As expected, eligible applicants referred by agencies not designed to provide continuity in outpatient care (e.g., hospitals, shelters) enrolled in the project at a higher rate than applicants referred by community mental health centers and other agencies with a high level of continuity of care (66% [N=125] versus 43% [N=52]) (χ2=15.14, df=1, p<0.001). This was true for those with a service assignment preference (65% [N=56] versus 44% [N=31]) (χ2=7.25, df=1, p<0.01) as well as for those who did not express a preference (66% [N=69] versus 43% [N=21]) (χ2=7.59, df=1, p<0.01), suggesting that the applicant’s need for outpatient psychiatric care was a primary motivation for study enrollment. There were no age, gender, or ethnicity differences between the two referral source groups.

More eligible applicants expressed a preference for clubhouse as opposed to a preference for PACT (Table 1). Applicants preferring assignment to PACT were more likely to be female (63% [N=42]) than were applicants preferring clubhouse (52% [N=47]) or having no preference (44% [N=67]) (χ2=6.53, df=3, p<0.05), but these three groups were comparable in age and ethnicity. Eligible applicants’ reasons for wanting to be assigned to PACT or clubhouse were often an expression of avoidance: one-third of applicants preferring assignment to PACT (31% [N=21]) simply wanted to avoid having to relinquish their current day program for the clubhouse, while about half of those preferring assignment to clubhouse (54% [N=49]) wanted to avoid relinquishing their current clinical services for PACT. Since the latter 49 applicants represented 70% of those reluctant to switch from existing services, the reluctance to switch and pro-clubhouse variables were confounded, and only reluctance to switch was included as a predictor variable in the analysis of time to project enrollment.

Almost 30% (N=133) of the applicants decided not to enroll, with an almost even split between those who did not want to risk assignment to a nonpreferred program (N=70) and those who withdrew due to fragility, lack of interest, or perceived stigma (N=63). Applicants reluctant to exchange current services for new experimental ones enrolled in the project at a lower rate (37% [N=26]) than other applicants (63% [N=151]) (χ2=14.70, df=1, p<0.001). Also, applicants who wanted to be assigned to PACT enrolled in the research project at a higher rate (67% [N=45]) than those who had no preference (59% [N=89]) or who had wanted assignment to the clubhouse (47% [N=43]) (χ2=6.50, df=2, p<0.05). This was most likely because the only way to enroll in PACT was through the research project, while the clubhouse would return to open enrollment once study recruitment was completed. Because a higher percentage of eligible applicants had been pro-clubhouse, the greater enrollment of pro-PACT applicants did not cause an imbalance. The final group of enrollees had just as many participants who preferred the clubhouse (24% [N=43]) as preferred PACT (25% [N=45]) and just as many who wanted to avoid exchanging a current day program for the clubhouse (7% [N=13]) as wanted to avoid exchanging current clinical services for PACT (7% [N=13]).

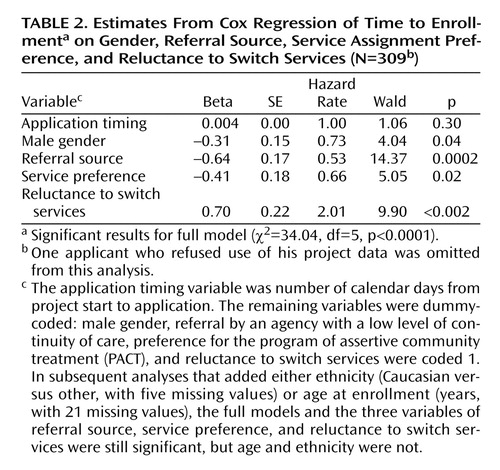

The results of a Cox regression analysis that controlled for date of application (Table 2) confirm that applicants from agencies with a low level of continuity of outpatient care enrolled more quickly than applicants from agencies with a high level of continuity of care. Applicants who preferred assignment to PACT also enrolled faster, and those reluctant to exchange current services for new ones took longer to enroll. As the hazard rate shows, applicants reluctant to switch services were twice as likely as other applicants to withdraw their applications. These same findings are obtained when ethnicity (five missing cases) and age (21 missing cases) were added as regression model covariates.

Predictors of Service Program Engagement

Applicants from agencies with a high level of continuity of outpatient care had equivalent rates of service engagement (84%) to those from agencies with a low level of continuity of care (87%), and these two groups were comparable in demographics. On the other hand, fewer enrollees who were mismatched to their service preference (75% [N=35]) became active in their assigned program compared with matched enrollees (93% [N=38]) and enrollees with no service preference (90% [N=77]) (χ2=7.69, df=2, p<0.05).

As Table 1 shows, the clubhouse was assigned more enrollees who were matched to their service preference as well as more enrollees who had not wanted to be assigned there. That is, the clubhouse received 20% more participants than PACT who had any service preference (60% versus 40%) (χ2=9.10, df=1, p<0.01). Fortunately, preference-matched, mismatched, and no-preference enrollees had equivalent rates of schizophrenia spectrum disorder diagnoses (52%, 51%, and 52%, respectively) and were similar in other background variables, allowing statistical control of program preference in service engagement and employment analyses.

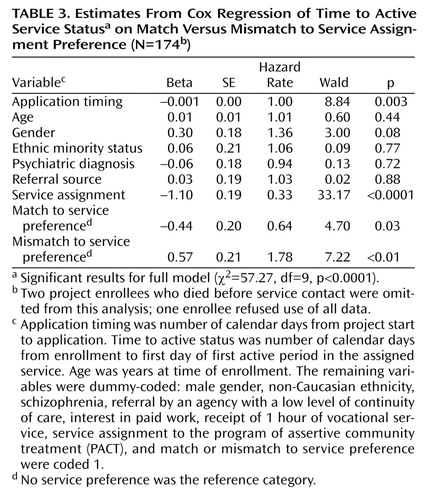

The results of a Cox regression analysis (Table 3) show that, when we controlled for background characteristics and timing of application, enrollees mismatched to their nonpreferred program took longer to engage in services than participants with no assignment preference, while enrollees matched to their service preference became engaged faster. The interaction between program and mismatch to preference and the interaction between program and match to preference were not significant when included in the analysis, and significant main effects for match and mismatch held for both programs. When entered as a separate block, match and mismatch significantly improved the fit of the regression model: the difference between the –2 log likelihoods of the full versus reduced model was significant (χ2=17.72, df=9, p<0.001).

Predictors of Competitive Employment

Univariate analyses revealed no significant differences in employment rates between participants assigned to the service they wanted (46% [N=19]), those assigned to the service they did not want (43% [N=20]), and those who had no assignment preference (58% [N=49]), or between referees from agencies high (50% [N=26]) versus low (50% [N=62]) in continuity of outpatient care. Competitive employment rates were fairly comparable for PACT (55% [N=47]) and clubhouse (47% [N=41]), and participants in both programs began their first competitive job an average of 7 months after enrollment. A fourth of all employed PACT participants (26% [N=12]) and 42% of employed clubhouse participants (N=17) took their first competitive job within 90 days. Interestingly, employed PACT participants were more likely to be men (68% [N=32]), while employed clubhouse participants were more likely to be women (66% [N=27]) (χ2=10.11, df=1, p<0.01).

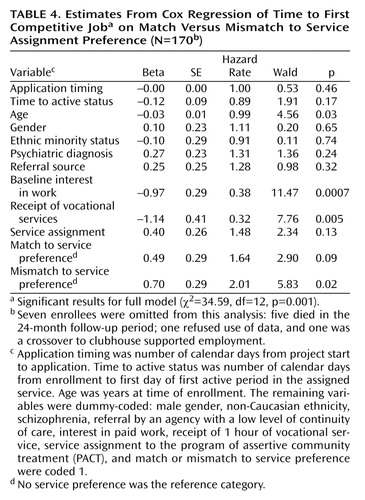

A Cox regression analysis (Table 4) revealed a significant main effect for mismatch to service preference that parallels the main effect obtained in the Cox regression analysis of service engagement and contradicts the univariate employment findings. When we controlled for length of time to service engagement, program assignment, demographics, and two work-related background variables (baseline interest in work and receipt of at least 1 hour of vocational services), enrollees mismatched to their service preference took significantly longer to begin a competitive job than those who had no service preference. As the hazard rate shows, applicants mismatched to a service they did not want were twice as likely to never become employed as applicants with no service preference. When entered as a separate block, match and mismatch significantly improved fit of the regression model: the difference between the –2 log likelihoods of the full versus the reduced model was significant (χ2=7.12, df=12, p<0.05). Positive main effects were also obtained for interest in work and receipt of vocational services, in keeping with earlier published findings (26). All covariate interactions were nonsignificant.

Survival Function Plots

Figure 1 shows the survival functions for PACT and clubhouse participants mismatched to their service preference compared with participants either matched with their preferred service or without a preference. The left panel plots these unadjusted survival functions for time to service engagement, and the right panel plots the functions for time to first competitive job. In each panel, the probability that a participant will not become active in the assigned program or enter competitive work is plotted on the vertical axis for each point in time on the horizontal axis. The survival functions in both panels approach zero as service engagement increases, demonstrating that the probability of remaining inactive or unemployed decreases over time. The higher curves for those mismatched to their assignment preference in both PACT and clubhouse indicate that mismatched participants took longer to become engaged in both experimental programs. The Cox regression analyses demonstrate that this effect of being mismatched to service preference was statistically significant even after adjustment for the effects of other relevant variables.

Discussion

The results of the enrollment analysis demonstrate that service preferences can influence research project enrollment and limit sample representativeness to the extent that preference correlates with previous service experience or consumer characteristics. Results of the service engagement and employment analyses demonstrate that applicant service preference continues to be salient even after project enrollment, predicting both engagement in the assigned service and motivation to pursue service-related outcomes. Applicants randomly matched to their service preference were 64% more likely than applicants with no preference to become engaged in assigned services. Applicants mismatched to their service preference were 77% less likely to become engaged in services and twice as likely to never be competitively employed. Since service preference was relatively balanced within this comparison of two high-quality interventions (27), and since the clubhouse condition received by chance more pro-PACT and more pro-clubhouse enrollees, the effects of service preference were not immediately obvious. However, had a majority of the enrollees favored one program over another, even perfect equivalence through random assignment would have given the preferred program an unfair advantage, i.e., more matched and fewer mismatched enrollees. For this reason, applicant preferences for program assignment should be routinely measured and statistically controlled for in all mental health service evaluations.

Extent of the Problem Within Mental Health Services Research

Only a handful of published service evaluations have reported and controlled for diversity in sample recruitment sources or study applicants’ preferences in service assignment. Even fewer published studies describe experimental program requirements for relinquishing current services that would duplicate experimental ones, and it is unclear how often such expectations appear in informed consents. This widespread disregard of the potential for service assignment preference to bias research findings is particularly disheartening because the design of most evidence-based (randomized controlled) service evaluations predispose applicants to prefer one experimental condition over the other. Many service evaluations compare a new or better service with services as usual or with a control condition not designed to achieve the targeted outcomes, as when day treatment is the control condition for a study of competitive employment. Service preference is confounded with experimental program differences in such studies and, unless measured, is impossible to statistically control. For this reason, evidence-based practices that have been evaluated by randomized controlled evaluations that did not document and statistically control for enrollees’ service assignment preference may still lack evidence of effectiveness (28).

Recommendations for Future Research

Our study findings underscore the importance of routinely documenting research applicants’ current services, any reluctance to relinquish an existing service, and preference or dislike for experimental services. Our recruiters asked applicants for a verbal commitment to participate in either experimental service if randomly assigned there, and applicant responses to planned probes were recorded verbatim. Other researchers may also benefit from asking open-ended questions and tracking verbatim dichotomous responses. Checklists and rating scale measures could also be constructed. However, this added burden to researchers may be unreasonable, given the demonstrated strength of categorical predictors in the present study. The more difficult decision is whether to limit the sample to only those individuals who have no service preference or, instead, to invite all eligible applicants to enroll and statistically control for preexisting preferences. The former solution appears more rigorous if eligible nonenrollees can be tracked in the same way as enrollees (29, 30). The latter alternative is more practical if recruitment is costly or slow.

A pilot survey of the target population could provide an estimate of the prevalence of service preferences to guide research design decisions (31). The high rate of expressed preferences among our own study enrollees suggests that we would have greatly limited our study group’s size and representativeness had we chosen to include only applicants with no preference. Also, applicants sometimes indicated that they would hide their service preference if it would exclude them from the study, so no service preference as an inclusion criterion may be unfeasible. Regardless, recruiters should carefully explain randomization and expectations for participation in each study condition, especially if applicants are active in services that might duplicate or compete with experimental services. The applicant may not have a service assignment preference until he or she fully understands the research study.

Conclusions

The randomized controlled trial is the gold standard for psychiatric research, and it is well suited to most clinical intervention and pharmaceutical studies. However, inability to blind participants to their experimental assignment is the Achilles’ heel of services research. We must begin to measure and control for applicant preference in random assignment if we are to build a strong empirical base for evidence-based practice in mental health services.

|

|

|

|

Received Jan. 31, 2003; revision received July 15, 2003; accepted April 9, 2004. From McLean Hospital, Harvard Medical School; the University of California, San Francisco; Vanderbilt University, Nashville, Tenn.; the University of Massachusetts Medical School, Worcester; and Stanford University, Stanford, Calif. Address correspondence and reprint requests to Dr. Macias, Community Intervention Research, McLean Hospital, 115 Mill St., Belmont, MA 02478; [email protected] (e-mail). Supported by NIMH grant MH-060828, Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration collaborative agreement SM-51831, the van Ameringen Foundation, the Rhodebeck Charitable Trust, and Llewellyn & Nicholas Nicholas. The authors thank William Shadish, Danson Jones, and Charles Rodican for their thoughtful critiques of the manuscript.

Figure 1. Estimated Survival Functions for Time to Active Status and Time to First Job in Program of Assertive Community Treatment (PACT) and Clubhouse Experimental Interventions

1. Shadish WR, Cook TD, Campbell DT: Experimental and Quasi-Experimental Designs for Generalized Causal Inference. New York, Houghton Mifflin, 2002Google Scholar

2. Krause MS, Howard KI: What random assignment does and does not do. J Clin Psychol 2003; 59:751–766Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

3. Calsyn R, Winter J, Morse G: Do consumers who have a choice of treatment have better outcomes? Community Ment Health J 2000; 36:149–160Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

4. Meyer B, Pilkonis PA, Krupnick JL, Egan MK, Simmens SJ, Sotsky SM: Treatment expectancies, patient alliance and outcome: further analyses from the National Institute of Mental Health Treatment of Depression Collaborative Research Program. J Consult Clin Psychol 2002; 70:1051–1055Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

5. Shadish WR, Matt GE, Navarro AM, Phillips G: The effects of psychological therapies under clinically representative conditions: a meta-analysis. Psychol Bull 2000; 126:512–529Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

6. Kearney C, Silverman W: A critical review of pharmacotherapy for youth with anxiety disorders: things are not as they seem. J Anxiety Disord 1998; 12:83–102Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

7. Corrigan PW, Salzer MS: The conflict between random assignment and treatment preference: implications for internal validity. Eval Program Plann 2003; 26:109–121Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

8. Scholle SH, Peele PB, Kelleher KJ, Frank E, Jansen-McWilliams L, Kupfer DJ: Effect of different recruitment sources on the composition of a bipolar disorder case registry. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol 2000; 35:220–227Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

9. Yeh M, McCabe K, Hurlburt M, Hough R, Hazen A, Culver S, Garland A, Landsverk J: Referral sources, diagnoses, and service types of youth in public outpatient mental health care: a focus on ethnic minorities. J Behav Health Serv Res 2002; 29:45–60Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

10. Bogenschutz MP, Siegfreid SL: Factors affecting engagement of dual diagnosis patients in outpatient treatment. Psychiatr Serv 1998; 49:1350–1352Link, Google Scholar

11. Vanable PA, Carey MP, Carey K, Maisto S: Predictors of participation and attrition in a health promotion study involving psychiatric outpatients. J Consult Clin Psychol 2002; 70:362–368Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

12. Wahlbeck K, Tuunainen A, Ahokas A, Leucht S: Dropout rates in randomised antipsychotic drug trials. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2001; 155:230–233Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

13. Hofmann SG, Barlow DH, Papp LA, Detweiler MF, Ray SE, Shear MK, Woods SW, Gorman JM: Pretreatment attrition in a comparative treatment outcome study on panic disorder. Am J Psychiatry 1998; 155:43–47Link, Google Scholar

14. West SG, Sagarin BJ: Participant selection and loss in randomized experiments, in Research Design: Donald Campbell’s Legacy, vol II. Edited by Bickman L. Thousand Oaks, Calif, Sage Publications, 2000, pp 117–154Google Scholar

15. Coo JA, Carey MA, Razzano L, Burke J, Blyler CR: The pioneer: the Employment Intervention Demonstration Program, in Conducting Multiple Site Evaluations in Real-World Settings, vol 94. Edited by Herrell JM, Straw RB. San Francisco, Jossey-Bass, 2002, pp 31–44Google Scholar

16. Stein LI, Test MA: Alternative to mental hospital treatment, I: conceptual model, treatment program, and clinical evaluation. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1980; 37:392–397Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

17. Allness D, Knoedler W: The PACT Model: A Manual for PACT Start-Up. Arlington, Va, National Alliance for the Mentally Ill, 1998Google Scholar

18. Russert MG, Frey JL: The PACT vocational model: a step into the future. Psychosocial Rehabilitation J 1991; 14:7–18Crossref, Google Scholar

19. Anderson SB: We Are Not Alone: Fountain House and the Development of Clubhouse Culture. New York, Fountain House, 1998Google Scholar

20. Beard JH, Propst RN, Malamud TJ: The Fountain House model of psychiatric rehabilitation. Psychosocial Rehabilitation J 1982; 5:1–12Google Scholar

21. Propst R: Standards for clubhouse programs: why and how they were developed. Psychosocial Rehabilitation J 1992; 16:25–30Crossref, Google Scholar

22. First MB, Spitzer RL, Gibbon M, Williams JBW: Structured Clinical Interview for Axes I and II DSM-IV Disorders (SCID-P). New York, New York State Psychiatric Institute, Biometrics Research Department, 1996Google Scholar

23. Herinckx HA, Kinney RF, Clarke GN, Paulson RI: Assertive community treatment versus usual care in engaging and retaining clients with severe mental illness. Psychiatr Serv 1997; 48:1297–1306Link, Google Scholar

24. Allison PD: Event History Analysis: Regression for Longitudinal Event Data. Beverly Hills, Calif, Sage Publications, 1984Google Scholar

25. Brekke JS, Ansel M, Long J, Slade E, Weinstein M: Intensity and continuity of services and functional outcomes in the rehabilitation of persons with schizophrenia. Psychiatr Serv 1999; 50:148–162Link, Google Scholar

26. Macias C, DeCarlo L, Wang Q, Frey J, Barreira P: Work interest as a predictor of competitive employment: policy implications for psychiatric rehabilitation. Adm Policy Ment Health 2001; 28:279–297Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

27. Chambless DL, Hollon SD: Defining empirically supported therapies. J Consult Clin Psychol 1998; 66:7–18Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

28. Lavori PW: Placebo control groups in randomized treatment trials: a statistician’s perspective. Biol Psychiatry 2000; 47:717–723Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

29. Marcus SM: Assessing non-consent bias with parallel randomized and nonrandomized clinical trials. J Clin Epidemiol 1997; 50:823–828Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

30. Lambert MF, Wood J: Incorporating patient preferences into randomized trials. J Clin Epidemiol 2000; 53:163–166Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

31. Halpern SD: Prospective preference assessment: a method to enhance the ethics and efficiency of randomized controlled trials. Control Clin Trials 2002; 23:274–288Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar