Integration of Psychiatric and Vocational Services: A Multisite Randomized, Controlled Trial of Supported Employment

Abstract

OBJECTIVE: Although large-scale surveys indicate that patients with severe mental illness want to work, their unemployment rate is three to five times that of the general adult population. This multisite, randomized implementation effectiveness trial examined the impact of highly integrated psychiatric and vocational rehabilitation services on the likelihood of successful work outcomes. METHOD: At seven sites nationwide, 1,273 outpatients with severe mental illness were randomly assigned either to an experimental supported employment program or to a comparison/services-as-usual condition and followed for 24 months. Data collection involved monthly services tracking, semiannual in-person interviews, recording of all paid employment, and program ratings made by using a services-integration measure. The likelihood of competitive employment and working 40 or more hours per month was examined by using mixed-effects random regression analysis. RESULTS: Subjects served by models that integrated psychiatric and vocational service delivery were more than twice as likely to be competitively employed and almost 1½ times as likely to work at least 40 hours per month when the authors controlled for time, demographic, clinical, and work history confounds. In addition, higher cumulative amounts of vocational services were associated with better employment outcomes, whereas higher cumulative amounts of psychiatric services were associated with poorer outcomes. CONCLUSIONS: Supported employment models with high levels of integration of psychiatric and vocational services were more effective than models with low levels of service integration.

Rigorous study of vocational rehabilitation for patients with schizophrenia and other severe mental illnesses has predominantly focused on testing the efficacy of model programs. Reviews of randomized, controlled trials of supported employment (1, 2) have established this approach as an evidence-based practice in returning psychiatric outpatients to competitive employment. However, the randomized, controlled trial design is subject to constraints related to the difficulties of replicating model programs under varying environmental conditions with diverse populations in a variety of organizational settings (3). Even when models are successfully implemented with a high degree of fidelity, the “black box” phenomenon persists, preventing the identification of relationships between specific active ingredients (e.g., specific model features, types, and amounts of vocational services) and successful patient outcomes (4).

In contrast, “implementation effectiveness trials” (5) evaluate models with established efficacy by testing them in real-world settings with varying program implementation and patient acceptance. The combination of this approach with a health services research design offers the benefits of random assignment, along with complex multivariate analysis of the effects of specific services on vocational outcomes (6, 7).

A major feature of evidence-based supported employment tested in randomized, controlled trials is a high degree of integration of psychiatric and vocational services (8, 9). Service integration can occur in a variety of different ways within diverse settings and programs. Individual staff can provide both clinical and vocational services (using a generalist model) or deliver only employment services (using a vocational specialist model). Providers are typically part of multidisciplinary teams of psychiatrists, case managers, and vocational staff, but team members may have responsibility for either an individual caseload or a shared caseload. Advantages of this type of integration in supported employment include an enhanced ability to engage and retain patients, more efficient and effective communication between different types of providers, enlistment of clinical staff in support of patients’ vocational attainment, and incorporation of clinical issues into the vocational rehabilitation process (9). Integrated services can be delivered in a variety of organizational settings, including outpatient clinics, community mental health centers, and rehabilitation programs by using a number of different models, including individual placement and support (10), a program of assertive community treatment (11), integrated services (12), and other models of supported employment that have been specially tailored for psychiatric populations.

Services research approaches have been applied less frequently in studies of supported employment. Several studies of psychiatric outpatients have found positive associations between successful work outcomes and amounts of vocational services (13, 14). However, to date, we know of no studies that have examined the effects of types and amounts of vocational services on employment outcomes while taking into account 1) service integration, or the degree to which employment services are coordinated with psychiatric services by providers who work for the same organization in the same location, interacting with one another frequently, and sharing information in a single case record and 2) patient demographic and clinical characteristics (7).

Given prior research, this study tested two hypotheses: 1) participants in supported employment programs with highly integrated psychiatric and vocational service delivery will achieve superior vocational outcomes compared to those in programs with low levels of integration, and 2) the amount of vocational services received will be positively associated with better employment outcomes after control for the amount of psychiatric services received as well as participant demographic and clinical characteristics.

Method

Multisite Study Background

The Employment Intervention Demonstration Program was funded in 1995, with the selection of eight study sites located in Maryland, Connecticut, South Carolina, Pennsylvania, Arizona, Massachusetts, Maine, and Texas. Organized under the cooperative agreement funding mechanism (Request for Applications SM 94-09), researchers and federal personnel collaborated in the development and implementation of a common protocol of research instruments, uniform data collection methods, and statistical analyses (15). This effort was led by a coordinating center based at the Department of Psychiatry at the University of Illinois at Chicago in partnership with the Human Services Research Institute located in Cambridge, Mass.

Study Participants

All of the study subjects met diagnosis, duration, and disability criteria for severe and persistent mental illness, as defined by the federal Center for Mental Health Services (15), along with the following inclusion criteria: age 18 years or older, interest in working, and ability to provide informed consent. At all sites, the subjects were recruited from clinical populations by provider referral, self-referral, family referral, or word of mouth. Advertisements in newspapers were also used by the Massachusetts site. Each site received approval from its local internal review board for the protection of human subjects and obtained written informed consent from all participants. The eligible pool of study participants numbered 10,653; of this group, 2,883 were contacted about participation (the numbers excluded the Massachusetts site, which was unable to provide this information). Across all sites (including Massachusetts), 1,750 individuals consented to participate in the study, 1,655 completed the first interview, and 1,648 were randomly assigned. Among those who agreed to participate but were never randomly assigned, the reasons included patient refusal, patient noneligibility, and patient loss to follow-up.

Of the 1,648 who were randomly assigned to groups, 375 were excluded from this analysis for the following reasons:

| 1. | Being employed at baseline (this included all 182 Pennsylvania participants), given that site’s focus on serving patients who were already working, as well as 28 additional participants from other sites who were later determined to have been employed at the time of study entry | ||||

| 2. | Sixty-five subjects in a second comparison condition in Connecticut, given the Employment Intervention Demonstration Program Steering Committee’s decision, made at the study’s outset, to conduct all cross-site analyses using a uniform data set comprised of two conditions at each site | ||||

| 3. | One hundred subjects for whom no vocational outcome data were available | ||||

No participants were excluded for any other reason, given the “intent to treat” design of the demonstration. Recruitment occurred between February 1996 and May 2000, and all participants received a monetary stipend for each interview. A total of 1,273 subjects were included in the analysis, distributed as follows: Maine (N=108), Connecticut (N=133), Massachusetts (N=166), Maryland (N=197), South Carolina (N=142), Texas (N=233), and Arizona (N=294).

Models Tested

Given the study’s design as a randomized implementation effectiveness trial (5), the sites tested different models of supported employment and compared them to a variety of conditions. At each site, the experimental condition was a form of enhanced best-practice supported employment (13) compared to either services as usual or an unenhanced version of the experimental model. The Maryland, Connecticut, and South Carolina sites tested the individual placement and support model in which multidisciplinary provider teams engage in minimal prevocational assessment, rapid job search, and placement into competitive jobs, with the provision of training and ongoing follow-along support for as long as the patient requests it. The Massachusetts site used the program of assertive community treatment vocational model, with services provided exclusively in the community through a mobile team comprised of psychiatrists, nurses, case managers, and vocational specialists who collaborate in placing patients in competitive employment and providing job training and continuous employment support. The remaining three sites used models developed especially for the Employment Intervention Demonstration Program. The Texas site combined “rapid placement” supported employment services with social network enhancements that were specifically designed to help patients create more balanced and reciprocal interpersonal networks that supported their work efforts. The Maine site used family-aided assertive community treatment teams whose vocational staff worked with an employer consortium of the area’s major businesses to develop job opportunities, workplace supports, and reasonable accommodations for workers with severe mental illness. The Arizona site used an integrated treatment team composed of psychiatrists, case managers, rehabilitation counselors, employment specialists, job developers, and benefits specialists emphasizing rapid job placement and ongoing support for job retention and career advancement.

Control Conditions

Because of ethical considerations, none of the sites used a “no treatment” comparison condition. Since the subjects entered the study desiring vocational rehabilitation, it was neither possible nor desirable to prevent them from receiving employment services. Thus, as with many multisite studies, the nature of the comparison conditions varied. Arizona, Connecticut, Maryland, and South Carolina used a services-as-usual comparison condition in which the subjects received whatever services were available in the local community. Massachusetts used the Clubhouse model (16, 17), in which facility-based services were provided according to a work-ordered day, with patients and staff working together on jobs within the program as well as at job placements in the community. Both Texas and Maine used an “unenhanced” version of their experimental condition (i.e., no social network services in Texas and no employer consortium in Maine).

Measures

Dependent variables

The two vocational outcome measures used in this study were selected to represent fundamentally different conceptualizations of employment success. The first, competitive employment, was defined in the original Request for Applications grant as a job that 1) pays the minimum wage or higher; 2) is located in a mainstream, socially integrated setting; 3) is not set aside for persons with disabilities; and 4) is held independently (i.e., is not agency owned). This outcome evaluates the subjects’ ability to vie with nondisabled workers for a job in the competitive labor market. The second outcome variable, work for 40 or more hours in a single month, is a measure used by the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services in their demonstration program titled “Demonstration to Maintain Independence and Employment” (Catalog of Federal Domestic Assistance number 93.779, issued June 7, 2000). This outcome evaluates the intensity of employment in terms of a minimum number of hours worked during a 1-month period.

Service-Delivery Integration

All of the experimental programs integrated the provision of vocational and psychiatric services through multidisciplinary teams. Team members adhered to a program philosophy emphasizing rapid, permanent, competitive employment in a field of the patient’s choosing, followed by ongoing support with no time limits. However, at some sites, the comparison model also involved delivery of highly integrated psychiatric and vocational services. Therefore, to operationalize the level of integration, an Employment Intervention Demonstration Program measure was developed in which programs were rated independently according to the following criteria:

| 1. | Psychiatric and vocational services were provided through multidisciplinary teams on which psychiatric and vocational staff interacted on a face-to-face basis at least three times a week or more. | ||||

| 2. | Psychiatric and vocational services were delivered by staff operating at the same location. | ||||

| 3. | Both types of services were provided by the same agency. | ||||

| 4. | A single case record was used | ||||

“Multidisciplinary teams” were defined as designated units that included (at a minimum) psychiatrists, case managers, job developers, and employment support staff who met in person usually daily but no less than 3 times per week. “Same location” was defined as having offices in a single building and “same agency” as a single organizational unit. “Single case record” was defined as a file that incorporated employment assessments and treatment plans, vocational outcome data, medication information, and case management notes. Each of the 14 programs was rated on each of the four integration criteria: four programs met 100% of the criteria, three met 75%, two met 50%, one met 25%, and four met 0%, resulting in a service-delivery integration variable with a mean of 53 and a median of 62. Inspection of this score revealed that its distribution was bimodal; therefore, the services-integration score was dichotomized so that programs meeting less than 50% of the criteria were classified as low in integration and otherwise as high.

Service types and amounts

In addition to service-delivery integration, the effects of the number of hours of psychiatric and vocational services were examined separately. Psychiatric services included 1) evaluation and diagnosis, 2) medication evaluation and management, 3) individual counseling, 4) family or couples counseling, 5) group counseling, 6) case management, 7) psychosocial rehabilitation/partial hospitalization, and 8) emergency services. Vocational services included 1) vocational assessment and evaluation, 2) vocational treatment planning/career counseling, 3) job development and placement, 4) off-site job skills training and education, 5) off-site vocational counseling, 6) on-site job support, 7) vocational support groups, 8) collaboration with employers, 9) job-related collaboration with family and friends, and 10) job-related transportation. For this analysis, a running cumulative total of service hours for each of the two types of services was calculated monthly for each of the 24 months of the study. For example, a patient’s total hours of vocational services for month 3 included all employment services received up to and including the third month of study participation, whereas a patient’s total hours of psychiatric services for month 24 included all psychiatric service hours over the past 2 years of participation in the Employment Intervention Demonstration Program.

Control Variables

Dichotomous variables based on the subjects’ reports at baseline were used for gender, minority status (white/Caucasian versus all others), and education (high school or more). Age was measured in 10-year intervals. The Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV (18) was administered at two sites by the project researchers, while case record diagnoses made by treating psychiatrists were extracted from clinical files at the remaining sites. Level of functioning, defined as the ability to function in non-work-related domains, such as independent living and social relationships, was self-rated by the subjects using a single Likert-scale item with response options of “poor,” “fair,” “good,” or “excellent.” Prior work history was reported by the subjects and coded as one or more jobs in the past 5 years versus none. Receipt of public disability income was reported by the subjects and coded as Supplemental Security Income (SSI) alone, Social Security Disability Income (SSDI) alone, or SSI plus SSDI (with no public disability income as a contrast). An independent psychometric evaluation of the Employment Intervention Demonstration Program’s common protocol (19) found good to excellent validity and reliability on the measures described.

Follow-Up Rates and Attrition Analysis

Of the 1,273 participants, 824 (65%) completed five interviews, 173 (14%) completed four interviews, 122 (9%) completed three, 111 (9%) completed two, and the remaining 43 (3%) completed one interview. Those completing five interviews were compared to all others regarding model covariates. The only significant differences were in gender and age: 51% (N=420) of completers were men versus 58% (N=258) of the noncompleters (χ2=4.92, df=1, p<0.05); the completers were 1 year older than the noncompleters (mean=39, SD=9, versus mean=38, SD=10) (t=–2.24, df=1270, p<0.05).

Statistical Analysis

After calculation and inspection of frequency distributions and zero-order relationships, outcomes were inspected visually for each of the 24 months of study participation. Next, random-effects logistic regression modeling, part of a family of statistical methods termed random regression models, was used to address hypotheses at the multivariate level. This approach was chosen to address issues commonly found in longitudinal multisite data, including serial correlation, individual heterogeneity, missing observations, and fixed versus time-varying covariates (20). All models included patient demographic characteristics (age, gender, race/ethnicity, education, work history, and SSI/SSDI status), clinical factors (schizophrenia spectrum diagnosis, level of functioning), time, and study site. In step 1, the effects of high versus low service integration were entered into the model; in step 2, the effects of the vocational and psychiatric services measures were added to the previous model, including the services-integration variable. Given the hypothesis-driven nature of the study, higher-order interactions between model variables were assumed to be nonsignificant.

Results

Participant Characteristics

Just over half of the subjects (N=678, 53%) were men, two-thirds (N=839, 66%) had a high school education or greater, half (N=636, 50%) were Caucasian, 30% (N=380) were African American, 14% (N=184) were Hispanic/Latino, 3% were American Indian, and the remainder were of other races/ethnicities. Their ages ranged from 18 to 76 years, with a mean and median of 38. The majority (N=763, 64%) reported holding one or more jobs in the 5 years before the baseline. Self-rated levels of functioning at baseline were characterized as poor by 15% (N=189), fair by 40% (N=509), good by 31% (N=396), and excellent by 14% (N=172). At baseline, 35% (N=437) reported receiving SSI, 25% (N=307) received SSDI, 12% (N=153) received both, and 28% (N=353) received neither. On axis I, half of the subjects (N=646, 51%) had a primary or secondary diagnosis of schizophrenia spectrum disorder, 21% (N=264) had major depression, 16% (N=206) had any bipolar disorder, 4% (N=45) had dysthymia or depressive disorder, 3% (N=43) had any psychosis, 1% (N=13) had posttraumatic stress disorder, and the remaining 4% (N=56) had other disorders, including anxiety, panic, delusional, dissociative, obsessive-compulsive, and somatization disorders.

Although all experimental condition programs met the criterion for high integration, at two of the seven sites (Maine and Texas), the comparison conditions also met this criterion. Thus, more study participants were served by programs with high levels of integration and fewer by programs with low levels of integration (N=811, 64%, versus N=462, 36%, respectively). Table 1 presents analyses of subject characteristics by high versus low level of service-delivery integration. There were no differences between the two groups in education, gender, diagnosis, level of functioning, age, or SSDI and SSI/SSDI beneficiary status. There were significant differences: a higher proportion of Caucasians as well as patients with recent work histories and a lower proportion of SSI beneficiaries were enrolled in high-integration programs. These three factors were controlled in all subsequent phases of the analysis. In addition, the study site was also controlled to account for the classification of all Maine and Texas subjects as receiving highly integrated services, as well as other potential differences among sites that may have remained unmeasured and unaccounted for. Even though integration was operationalized separately from hours of vocational and clinical services, there was a weak yet significant correlation between total average hours of vocational services and integration (r=0.19, p<0.0001), in which patients in high-integration programs received a greater number of hours of vocational services than those in low-integration programs. However, there was no difference in psychiatric services between the high- and low-integration programs.

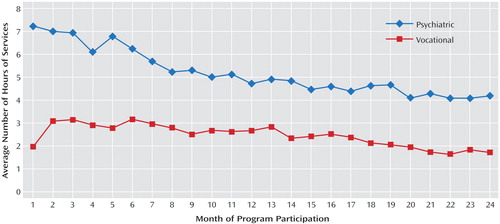

Vocational and Psychiatric Services

Figure 1 shows the average (per person) number of hours of psychiatric and vocational services received by all patients for each of their 24 months of program participation, with adjustment for the subjects’ varying calendar months of participation. Starting with their first month, on average, the patients received twice as many hours of psychiatric services as vocational services: an average of 7.2 hours of psychiatric and 1.9 hours of vocational services in month 1, 4.7 hours versus 2.6 hours in month 12, and 4.2 hours versus 1.7 in month 24). In addition, the average monthly hours of service per patient decreased over time for both psychiatric and vocational services.

Study Condition and Services Integration

As reported in a separately published analysis of the original experimental versus comparison study conditions (21), there were significant differences by study condition for both vocational outcomes. Over the course of the study, 55% (N=359) of the experimental participants achieved competitive employment compared to 34% (N=210) of the subjects in the comparison condition (p<0.001). A similar but more modest difference was seen for the second vocational outcome, with 51% (N=330) of the subjects in the experimental condition having worked for at least 40 hours in at least 1 month compared to 39% (N=245) of the subjects in the comparison condition (p<0.001).

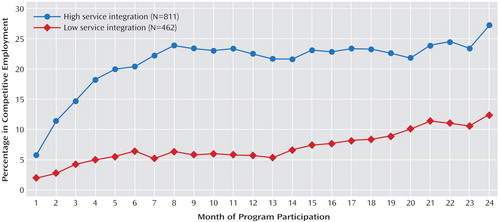

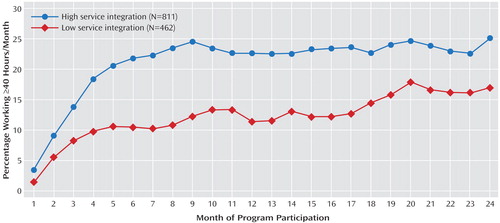

To test the present study’s first hypothesis, client outcomes were compared according to whether they were served in models with high versus low integration of psychiatric and vocational service delivery. Over the 24-month course of the study, a larger proportion (N=471, 58%) of the participants in the high-integration services programs achieved competitive employment compared to 21% (N=98) of the subjects in the low-integration programs (χ2=161.8, df=1, p<0.001). For the second vocational outcome, working 40 or more hours in a month, more than half (N=431, 53%) of the high-integration participants worked for at least 40 hours in a month compared to 31% (N=144) of the low-integration participants (χ2=57.4, df=1, p<0.001).

Figure 2 and Figure 3 show the proportion of patients over time who achieved an outcome by their month of participation in the study. Starting with month 1 and continuing throughout the study, a larger proportion of the high-integration participants achieved competitive employment (Figure 2) and 40 or more hours of work in a month (Figure 3) than did the low-integration participants. The highest proportion working competitively in any month of study participation was around 27%, achieved by high-integration patients, whereas the highest percentage working 40 or more hours in a month was around 25%, again achieved by the high-integration group. These findings are consistent with hypothesis 1.

High Versus Low Service Integration

To test hypothesis 1 at the multivariate level, random regression models were computed by using high versus low service-delivery integration as the independent variable. In step 1, patient demographic and clinical characteristics, time, and study site were entered along with the level of integration. In step 2, the effects of hours of vocational and psychiatric services were added to the model used in step 1. As shown in Table 2, the estimated odds ratios for the two outcome variables were significant, so that participants in programs with high integration had better outcomes than those with low integration. Specifically, participants in high-integration programs were more than twice as likely to work competitively and were 1¼ times as likely to work 40 or more hours in a month. This analysis also controlled for study site as well as client demographic, illness, work history, and disability income beneficiary features.

Psychiatric Versus Vocational Services

In step 2, the models were further specified by the addition of two covariates: one measuring monthly cumulative hours of psychiatric services and a separate cumulative measure of monthly vocational services. The results in step 2 (Table 2) show that the total cumulative hours of vocational services were significantly associated with a greater likelihood of both competitive employment and working ≥40 hours per month. This is indicated by the fact that the odds ratio for vocational services measured in hours exceeded 1. On the other hand, the total cumulative hours of psychiatric services were significantly associated with the lesser likelihood of the two outcomes. This is shown by the fact that the odds ratio for hours of psychiatric services was lower than 1.

The results of step 2 also show that even after we controlled for the cumulative amounts of both types of services, patients in highly integrated service-delivery programs had superior employment outcomes. This is indicated by the fact that the two odds ratios for the integration effect remained significant for both outcomes in step 2 and also increased in size. Thus, service-delivery integration had a distinct and significant association with work outcome.

Because the two services variables were entered into the models as interval-level variables, their odds ratios are somewhat difficult to interpret. To clarify the association between services and outcomes, we dichotomized the two service variables by dividing them at the median for each month, classifying respondents as receiving “high” versus “low” amounts (in hours) of each. This allowed us to examine the effects of services when they were operationalized in a manner similar to that used for the other model variables. After we entered these dichotomized services variables in step 2 of the models described earlier, the participants receiving a high number of hours of vocational services were almost 2½ times as likely to work competitively (odds ratio=2.41, p<0.001) and were almost twice as likely to work 40 or more hours in a month (odds ratio=1.97, p<0.001). Conversely, psychiatric services had a weaker effect on vocational outcomes: those receiving high amounts of psychiatric services were four-fifths as likely to work competitively (odds ratio=0.79, p<0.001) and were 7% less likely to work ≥40 hours per month (odds ratio=0.93, p<0.001).

A final step in our analysis involved testing for an interaction effect between the two types of services. When we used step 2 variables in our models, the results (not shown) revealed a significant interaction effect in which individuals who received high amounts of vocational services did best, regardless of whether they also received high or low amounts of psychiatric services. Thus, the intensity of employment services was related to success, regardless of the intensity of the psychiatric services received.

Discussion

The results of this analysis confirm that supported employment models in which psychiatric and vocational service delivery are highly integrated produce better vocational outcomes. The participants served in programs in which clinical and vocational staff worked together in multidisciplinary teams at the same location using a unified case record and meeting together multiple times per week were more likely to work competitively and to work 40 or more hours per month.

At the same time, however, participants in the Employment Intervention Demonstration Program received many more hours of psychiatric services, on average, than vocational services. This is noteworthy because after we controlled for all other factors, those who received more hours of vocational services had better employment outcomes, whereas those who received more hours of psychiatric services had poorer employment outcomes. It may be that those who received more psychiatric service hours had more disabling disorders and were thus more clinically impaired, requiring more psychiatric assistance and being less likely to work. On the other hand, results regarding vocational services support the notion that those who receive more of these types of services achieve significantly better outcomes, even after control for the amount of psychiatric services they receive. This confirms the findings of prior research in which clients with better outcomes received more employment-specific vocational services (13) and, perhaps related to this factor, stayed in vocational programs for longer periods of time (22).

Because participants who received more vocational services had better employment outcomes, it appears to be critically important for programs to monitor the amount of vocational services they deliver and to continue to serve patients who want and need services with no time limits, even after clients are working successfully. In addition, patients may benefit from greater amounts of vocational services to complement or even exceed the levels of psychiatric services they are offered. Programs that purport to deliver vocational services but instead deliver large amounts of psychiatric services and low levels of vocational services may not achieve good employment outcomes.

In this study, services integration was defined as vocational and psychiatric services (such as medication management and individual therapy) provided by the same agency at the same location with all the information about the client combined into a single case record and with regularly and frequently scheduled staff meetings (usually daily or at least 3 times per week) to coordinate treatment planning and service delivery while enhancing staff communication and coordination. The study’s results confirm the importance of provider communication and the coordination of psychiatric and rehabilitation services in working toward vocational goals. Patients who receive psychiatric services from one provider agency and employment services from another and whose psychiatric and employment service providers do not interact frequently or share information in a single case file had significantly poorer outcomes, all other things being equal.

Although the patients who received higher levels of vocational services achieved better vocational outcomes, the additional significant effect of being in a high-integration service-delivery program, in the face of many other variables, suggests that high-integration programs contain active ingredients that exceeded the effects of services alone. These programs’ incorporation of the latest rehabilitation technology based on the best practices in psychiatric vocational rehabilitation, as well as advances in psychotropic medications, may have contributed to their success (23–25). Alternatively, other unmeasured factors may be driving the results, such as uncontrolled variation between sites or multiple causation. It remains for further analysis of data from the Employment Intervention Demonstration Program to explore the relative effects of these best practices, such as rapid job development, placement in positions according to client preferences, and provision of ongoing support, to better understand these important processes.

Study limitations include the fact that the study subjects were not a representative sample of adults with severe mental illness, which limits the generalizability of the results. In addition, the study’s measure of service-delivery integration was somewhat crude, tapping only four dimensions of an admittedly complex construct, and was administered at the time of program maturity, whereas integration undoubtedly varied, especially during program startup. Measures of service volume were also simplified by monthly summation, when it is also possible that both psychiatric and vocational services do not have a simple, additive effect. Finally, there is also some redundancy between the likelihood of being employed and the chances of receiving some types of vocational services, which may influence the study’s findings.

Given that a substantial proportion of unemployed psychiatric outpatients live below the poverty level (26, 27) and a high proportion depend on public disability income support as an economic “safety net” (28), employment may be the difference between making ends meet and doing without. The results of this study point to important service-delivery features associated with making work a reality for people with severe mental illness, creating the potential to alleviate poverty and improve their quality of life in the community.

|

|

Received May 14, 2004; revisions received Sept. 8 and Oct. 13, 2004; accepted Dec. 3, 2004. From the University of Illinois at Chicago; the University of Maryland, Baltimore; Dartmouth University, Concord, N.H.; Maine Medical Center, Portland; the Medical University of South Carolina, Charleston; the Human Services Research Institute, Cambridge, Mass.; the Center for Mental Health Services, Rockville, Md.; the Texas Department of Mental Health, Austin; Connections, CSP Incorporated, Wilmington, Del.; and the University of Arizona, Tucson. Address reprint requests to Dr. Cook, UIC Department of Psychiatry, 104 South Michigan Ave., Suite 900, Chicago, IL 60603, [email protected] (e-mail). Funded by Cooperative Agreement number SM51820. This study is part of the Employment Intervention Demonstration Program, a multisite collaboration among eight research demonstration sites, a coordinating center, and the Center for Mental Health Services, Substance Abuse, and Mental Health Services Administration. The views expressed herein are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the policy or position of any federal agency.

Figure 1. Average Number of Hours of Vocational and Psychiatric Services per Person by Month of Program Participation for 1,273 Outpatients With Severe Mental Illness

Figure 2. Proportion of Outpatients With Severe Mental Illness in Competitive Employment per Month by Integration of Psychiatric and Vocational Services

Figure 3. Proportion of Outpatients With Severe Mental Illness Working ≥40 Hours per Month by Integration of Psychiatric and Vocational Services

1. Lehman AF: Vocational rehabilitation in schizophrenia. Schizophr Bull 1995; 21:645–656Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

2. Twamley EW, Jeste DV, Lehman AF: Vocational rehabilitation in schizophrenia and other psychotic disorders: a literature review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. J Nerv Ment Dis 2003; 191:515–523Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

3. Essock SM, Drake RE, Frank RG, McGuire TG: Randomized clinical trials in evidence-based mental health care: getting the right answer to the right questions. Schizophr Bull 2003; 29:115–123Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

4. LaLonde RJ, Ham J: Looking into the black box: using experimental data to find out how training works. Int J Manpower 1994; 15:32–37Crossref, Google Scholar

5. Gordis L: Epidemiology, 2nd ed. Philadelphia, WB Saunders, 2000Google Scholar

6. Cook JA, Burke J: Public policy and employment of people with disabilities: exploring new paradigms. J Behav Sci Law 2002; 20:541–557Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

7. Cook JA: Understanding the failure of vocational rehabilitation: what do we need to know and how can we learn it? J Disability Policy Studies 1999; 10:127–132Crossref, Google Scholar

8. Bond GR: Supported employment: evidence for an evidence-based practice. Psychiatr Rehabil J 2004; 27:377–383Google Scholar

9. Drake RE, Becker DR, Bond GR, Mueser KT: A process analysis of integrated and non-integrated approaches to supported employment. J Vocational Rehabilitation 2003; 18:51–58Google Scholar

10. Drake RE, McHugo GJ, Bebout RR, Becker DR, Harris M, Bond GR, Quimby E: A randomized clinical trial of supported employment for inner-city patients with severe mental illness. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1999; 56:627–633Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

11. Russert MG, Frey JL: The PACT vocational model: a step into the future. Psychosocial Rehabilitation J 1991; 14:7–18Crossref, Google Scholar

12. Cook JA, Rosenberg H: Predicting community employment among persons with psychiatric disability: a logistic regression analysis. J Rehabilitation Administration 1994; 18:6–22Google Scholar

13. Cook JA, Razzano LA: Natural vocational supports for persons with severe mental illness: thresholds supported competitive employment program. New Dir Ment Health Serv 1992; 56:23–41Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

14. Finch JR, Wheaton JE: Patterns of services to vocational rehabilitation consumers with serious mental illness. Rehabil Couns Bull 1999; 42:214–227Google Scholar

15. Cook JA, Carey MA, Razzano LA, Burke J, Blyler C: The pioneer: the Employment Intervention Demonstration Program. New Directions for Evaluation 2002; 94:31–44Crossref, Google Scholar

16. Beard JH: The rehabilitation services of Fountain House, in Alternatives to Mental Hospital Treatment. Edited by Stein L, Test MA. New York, Plenum, 1987, pp 201–208Google Scholar

17. Anderson SB: We Are Not Alone: Fountain House and the Development of Clubhouse Culture. New York, Fountain House, 1998Google Scholar

18. First MB, Spitzer RL, Gibbon M, Williams JBW: Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Axis I Disorders, Patient Edition (SCID-P), version 2. New York, New York State Psychiatric Institute, Biometrics Research, 1995Google Scholar

19. Salyers MP, McHugo GJ, Cook JA, Razzano LA, Drake RE, Mueser KT: Reliability of instruments in a cooperative, multi-site study: Employment Intervention Demonstration Program. Ment Health Serv Res 2001; 3:129–140Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

20. Gibbons RD, Hedeker D, Elkin I, Waternaux C, Kraemer HC, Greenhouse JB, Shea MT, Imber SD, Sotsky SM, Watkins JT: Some conceptual and statistical issues in analysis of longitudinal psychiatric data: application of NIMH Treatment of Depression Collaborative Research Program dataset. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1993; 50:739–750Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

21. Cook JA, Leff HS, Blyler CR, Gold PB, Goldberg RW, Gold P, Mueser KT, Toprac MG, McFarlane WR, Shafer MS, Blankertz LF, Dudek K, Razzano LA, Grey DD, Burke-Miller J: Results of a multisite randomized trial of supported employment interventions for individuals with severe mental illness. Arch Gen Psychiatry 2005; 62:505–512Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

22. Cook JA, Razzano LA: Discriminant function analysis of competitive employment outcomes in a transitional employment program for persons with severe mental illness. J Vocational Rehabilitation 1995; 5:127–139Crossref, Google Scholar

23. Anthony WA, Rogers ES, Cohen M, Davies R: Relationships between psychiatric symptomatology, work skills, and future vocational performance. Psychiatr Serv 1995; 46:353–358Link, Google Scholar

24. Lindstroem LH, Lundberg T: Long-term effect on outcome of clozapine in chronic therapy-resistant schizophrenic patients. Eur Psychiatry 1997; 12:353S-355SCrossref, Medline, Google Scholar

25. Reker T, Eikelmann B: Work therapy for schizophrenic patients: results of a 3-year prospective study in Germany. Eur Arch Psychiatry Clin Neurosci 1997; 247:314–319Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

26. Cohen CI: Poverty and the course of schizophrenia: implications for research and policy. Hosp Community Psychiatry 1993; 44:951–959Abstract, Google Scholar

27. Polak P, Warner R: The economic life of seriously mentally ill people in the community. Psychiatr Serv 1996; 47:270–274Link, Google Scholar

28. Ho B-C, Andreasen N, Flaum M: Dependence on public financial support early in the course of schizophrenia. Psychiatr Serv 1997; 48:948–950Link, Google Scholar