Incidence of Newly Diagnosed Diabetes Attributable to Atypical Antipsychotic Medications

Abstract

OBJECTIVE: The purpose of the study was to determine the proportion of patients with schizophrenia with a stable regimen of antipsychotic monotherapy who developed diabetes or were hospitalized for ketoacidosis. METHOD: Patients with schizophrenia for whom a stable regimen of antipsychotic monotherapy was consistently prescribed during any 3-month period between June 1999 and September 2000 and who had no diabetes were followed through September 2001 by using administrative data from the Department of Veterans Affairs. Cox proportional hazards models were developed to identify the characteristics associated with newly diagnosed diabetes and ketoacidosis. RESULTS: Of the 56,849 patients identified, 4,132 (7.3%) developed diabetes and 88 (0.2%) were hospitalized for ketoacidosis. Diabetes risk was highest for clozapine (hazard ratio=1.57) and olanzapine (hazard ratio=1.15); the diabetes risks for quetiapine (hazard ratio=1.20) and risperidone (hazard ratio=1.01) were not significantly different from that for conventional antipsychotics. The attributable risks of diabetes mellitus associated with atypical antipsychotics were small, ranging from 0.05% (risperidone) to 2.03% (clozapine). CONCLUSIONS: Although clozapine and olanzapine have greater diabetes risk, the attributable risk of diabetes mellitus with atypical antipsychotics is small.

There is some evidence to suggest that atypical antipsychotics can cause weight gain and increased risk of diabetes mellitus (1–5). Other studies have suggested that there might be a link between atypical antipsychotics and diabetic ketoacidosis (6, 7). However, few published studies have examined diabetes mellitus prevalence (8) or risk of new-onset diabetes mellitus or diabetic ketoacidosis for patients treated with antipsychotics (6, 9), and, to our knowledge, no studies have reported diabetes mellitus incidence rates in this population.

The goals of this study were to determine the proportion of patients with schizophrenia with a stable regimen of antipsychotic monotherapy who developed diabetes mellitus or were hospitalized for diabetic ketoacidosis and to identify patient demographic, clinical, and pharmacological characteristics associated with these adverse events.

Method

We identified 73,946 patients with schizophrenia in the Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) for whom a stable regimen of antipsychotic monotherapy was consistently prescribed during any 3-month period between June 1999 and September 30, 2000. We defined five groups of antipsychotic medications: clozapine, risperidone, olanzapine, quetiapine, and all conventional antipsychotics. Ziprasidone and aripiprazole were not included in the study because they had only recently been approved for use.

Patients with any outpatient claims for diabetes mellitus (N=11,069) or less than two medical primary care visits (N=6,028) in the previous 6 months were excluded from the sample. Stably medicated patients with no diabetes mellitus were followed through September 30, 2001. Patients who received a diagnosis of diabetes mellitus or who were hospitalized for diabetic ketoacidosis during that period were identified.

Cox proportional hazards models were used to model the time to diabetes mellitus diagnosis and time to diabetic ketoacidosis hospitalization. Independent variables included in the models were antipsychotic agent prescribed during the stable period, date of the end of the stable period, age, gender, race, income, comorbid mental health diagnoses, levels of service use during the stable period, and the degree of VA service-connected disability. We also calculated the attributable risk of diabetes mellitus and diabetic ketoacidosis associated with each atypical antipsychotic, which is the estimated proportion of patients taking each drug who would not have received a diagnosis of diabetes mellitus or diabetic ketoacidosis if they had been taking a conventional antipsychotic (10, p. 38).

Results

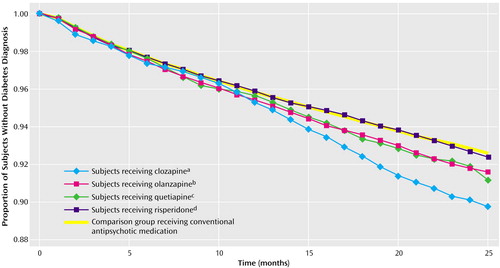

Of the 56,849 patients in the sample, 4,132 patients (7.3%) received a diagnosis of diabetes mellitus during the follow-up period, representing an annual incidence rate of 4.4%. Only 88 patients (0.2%) were hospitalized for diabetic ketoacidosis. Figure 1 shows the fitted survival functions associated with each medication group from the model predicting diabetes mellitus diagnosis. The attributable risk associated with these medications was highest for clozapine (2.03%), followed by quetiapine (0.80%), olanzapine (0.63%), and risperidone (0.05%).

In the diabetic ketoacidosis model, hazard ratios associated with atypical antipsychotics were larger than in the diabetes mellitus model, but the attributable risks were much smaller (ranging from 0.004% for risperidone to 0.071% for clozapine). In the entire sample, hazard ratios for diabetic ketoacidosis were significant only for clozapine (hazard ratio=3.75, 95% confidence interval [CI]=1.39–10.09) and olanzapine (hazard ratio=1.77, 95% CI=1.05–2.98). None of the hazard ratios for diabetic ketoacidosis were statistically significant when the analysis was limited to diabetes mellitus patients.

Discussion

The incidence of diabetes mellitus in this population was relatively high, even among patients for whom a stable regimen of a conventional antipsychotic was prescribed. The overall annual diabetes mellitus incidence rate of 4.4% in this study is considerably higher than the estimated rate of 6.3 cases per 1,000 in the general U.S. population (11). It is unclear how much of the increased diabetes mellitus incidence in the sample was due to the use of antipsychotic medications (conventional or atypical antipsychotics), the underlying disease of schizophrenia, or other factors such as poorer overall physical health, less healthy lifestyles, or poorer access to health care services.

Differences in diabetes mellitus risk across antipsychotic medications did not become apparent until 14 months after the end of the stable period (Figure 1). Hence, the additional diabetes mellitus risk associated with clozapine and olanzapine took more than a year to develop. This interval should offer ample time for clinicians to identify weight gain and/or elevated diabetes mellitus risk and perhaps to change the antipsychotic regimen accordingly.

Our results do not support the claim that weight gain and elevated risk of diabetes mellitus are a “class effect” of all atypical antipsychotic medications. In addition, the attributable risks of diabetes mellitus and diabetic ketoacidosis associated with atypical antipsychotics were small. However, diabetes mellitus and diabetic ketoacidosis are severe, life-threatening disorders, and while these attributable risks are small, they may still be of concern.

Several limitations of the study deserve comment. First, we examined the incidence of diabetes mellitus diagnosed in the VA system among patients with schizophrenia for whom a stable regimen of an antipsychotic medication was prescribed. Hence, our results may not be generalizable to other populations or health care systems. In addition, there may have been cases of diabetes mellitus that were undiagnosed or diagnosed outside of the VA. Although we were unable to identify undiagnosed diabetes mellitus cases, we have no reason to believe that the likelihood of failure to diagnose diabetes mellitus would be different across groups of patients for whom different antipsychotic medications were prescribed. Finally, our analysis attributed all of the diabetes mellitus risk to the atypical antipsychotic that was consistently prescribed for the patient during a 3-month window. Different medications may have been prescribed either before or after the medication identified in our study, and the increased risk of diabetes mellitus might be partially attributable to these other medications. Data were not available to identify medications taken earlier, and the proportions of patients whose drugs were switched during the follow-up period were small (17% overall) and were similar across medication groups.

Despite these limitations, the results offer insight into the risk of diabetes mellitus and diabetic ketoacidosis in an older, predominantly male population with schizophrenia for whom antipsychotic medications are prescribed.

Presented at the 55th Institute on Psychiatric Services, Boston, Oct. 29–Nov. 2, 2003. Received Jan. 7, 2004; revision received Feb. 25, 2004; accepted March 4, 2004. From the Department of Veterans Affairs Connecticut Mental Illness Research, Education and Clinical Center, West Haven, Conn.; and the Departments of Psychiatry and Epidemiology and Public Health, Yale School of Medicine, New Haven, Conn. Address reprint requests to Dr. Leslie, Northeast Program Evaluation Center/182, 950 Campbell Ave., West Haven, CT 06516; [email protected] (e-mail). Supported in part by the Department of Veterans Affairs, the NIMH Clinical Antipsychotic Trials of Intervention Effectiveness (J. Lieberman, principle investigator), and Bristol-Myers Squibb.

Figure 1. Fitted Survival Functions From the Cox Proportional Hazards Model Predicting Time to Diabetes Mellitus Onset Among Outpatients With Schizophrenia For Whom a Stable Regimen of Antipsychotic Monotherapy Was Prescribed

aHazard ratio=1.57, 95% confidence interval (CI)=1.31–1.89

bHazard ratio=1.15, 95% CI=1.07–1.24

cHazard ratio=1.20, 95% CI=0.99–1.44

dHazard ratio=1.01, 95% CI=0.93–1.10

1. Henderson DC, Cagliero E, Gray C, Nasrallah RS, Hayden DL, Schoenfeld DA, Goff DC: Clozapine, diabetes mellitus, weight gain, and lipid abnormalities: a five-year naturalistic study. Am J Psychiatry 2000; 157:975–981Link, Google Scholar

2. Gianfrancesco FD, Grogg AL, Mahmoud RA, Wang RH, Nasrallah HA: Differential effects of risperidone, olanzapine, clozapine, and conventional antipsychotics on type 2 diabetes: findings from a large health plan database. J Clin Psychiatry 2002; 63:920–930Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

3. Allison DB, Mentore JL, Heo M, Chandler LP, Cappelleri JC, Infante MC, Weiden PJ: Antipsychotic-induced weight gain: a comprehensive research synthesis. Am J Psychiatry 1999; 156:1686–1696Abstract, Google Scholar

4. Koro CE, Fedder DO, L’Italien GJ, Weiss S, Magder LS, Kreyenbuhl J, Revicki D, Buchanan RW: An assessment of the independent effects of olanzapine and risperidone exposure on the risk of hyperlipidemia in schizophrenic patients. Arch Gen Psychiatry 2002; 59:1021–1026Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

5. Citrome LL, Jaffe AB: Relationship of atypical antipsychotics with development of diabetes mellitus. Ann Pharmacother 2003; 37:1849–1857Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

6. Wilson DR, D’Souza L, Sarkar N, Newton M, Hammond C: New-onset diabetes and ketoacidosis with atypical antipsychotics. Schizophr Res 2003; 59:1–6Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

7. Jin H, Meyer JM, Jeste DV: Phenomenology of and risk factors for new-onset diabetes mellitus and diabetic ketoacidosis associated with atypical antipsychotics: an analysis of 45 published cases. Ann Clin Psychiatry 2002; 14:59–64Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

8. Sernyak MJ, Leslie DL, Alarcon RD, Losonczy MF, Rosenheck R: Association of diabetes mellitus with use of atypical neuroleptics in the treatment of schizophrenia. Am J Psychiatry 2002; 159:561–566Link, Google Scholar

9. Gianfrancesco F, White R, Wang RH, Nasrallah HA: Antipsychotic-induced type 2 diabetes: evidence from a large health plan database. J Clin Psychopharmacol 2003; 23:328–335Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

10. Kelsey JL, Whittemore AS, Evans AS, Thompson WD: Methods in Observational Epidemiology. New York, Oxford University Press, 1996Google Scholar

11. National Diabetes Fact Sheet: General Information and National Estimates on Diabetes in the United States, 2002. Atlanta, US Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2003Google Scholar