Use of Psychotropic Medications Before and After Sept. 11, 2001

Abstract

OBJECTIVE: This study examined patterns of psychotropic medication use after the Sept. 11, 2001, terrorist attacks. METHOD: It drew from two large pharmacy data sets, one providing nationally representative aggregate projections for all U.S. prescriptions (156.9 million claims for psychotropic medications during the study period) and a second from the nation’s largest pharmacy benefit management organization (36.4 million enrollees per month), 4.1% of whom had a prescription for a psychotropic medication during the study period. Analyses examined use of antidepressant, antipsychotic, anxiolytic, and hypnotic medications in the 12 weeks before and after Sept. 11, 2001, compared with the same weeks during 2000. RESULTS: Nationally and in Washington, D.C., there was no evidence of an increase in overall prescriptions, new prescriptions, or daily doses for psychotropic medications. In New York City, there was an increase in the proportion of existing users with psychotropic dose increases in the weeks after the attacks (16.9% in 2001 versus 13.6% in 2000) but no significant increase in the rate of new psychotropic prescriptions. CONCLUSIONS: For most of the nation, the distress associated with the terrorist attacks was not accompanied by a commensurate increase in the use of psychotropic medications. In New York City, there was a statistically significant but modest increase in the proportion of individuals with dose increases in their psychotropic medications.

The Sept. 11, 2001, terrorist attacks served as a grim natural experiment in how an unexpected, unpredictable, and frightening series of events affect the psyche of a country and its citizens. In the weeks after the attacks, national surveys described high levels of stress and anxiety (1–3), which, for New Yorkers, were followed by reports of elevated levels of posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) (4–6), depression (7), and substance use (8). Early assessments predicted that more than 500,000 individuals in the New York City area alone would develop PTSD (9), and national public health leaders worried that that the psychological sequelae of these attacks could overwhelm the country’s mental health system (10).

This study seeks to better understand how Americans coped with these attacks by examining changes in the use of psychotropic medications in the weeks following Sept. 11, 2001. Did the shock and distress following the attacks lead to increased use of psychoactive medications? If so, did this occur nationally or only in New York City, where the majority of the attacks occurred? And, if not, what does it say about Americans’ help-seeking behavior after the attacks?

Method

Study Sample

In order to ensure both breadth and depth of data about medication use, we used two sources for the study, each tracking psychotropic medication use in the weeks before and after Sept. 11, 2001. The first used a national data warehouse that collects information about more than two-thirds of the prescriptions in the United States and then projects these statistics to aggregate nationwide and regional estimates of medication use. The second, from the nation’s largest pharmaceutical benefits management company, provides longitudinal data to identify new prescriptions and track changes in drug doses for individuals. Because of the substantial proportion of U.S. prescriptions covered by both of these data sets, there is likely to be some overlap in their coverage, although they use distinct methods and sources for obtaining data, as we will describe.

NDCHealth

NDCHealth is the nation’s largest health care information service company, purchasing data on 2 billion prescription transactions annually. The data are continuously drawn from 35,000 of the 55,000 retail independent and chain pharmacies in the country and represent approximately 70% of all prescriptions filled in the United States. A three-stage process is used to generate weights that provide an unbiased projection of this sample of pharmacy claims to the universe of national outpatient pharmacy prescriptions in the United States. First, NDCHealth divides the country into 1,300 demographically homogeneous “dispensing zones” by using CACI International’s zip-code-based demographic and socioeconomic information. Within each of these zones, sample claims are adjusted to account for the proportion and patient characteristics of prescriptions filled at nonsample pharmacies by using data from Merck-Medco (now Medco), a national pharmaceutical benefit management company. The weights are further adjusted by using information about the volume of prescriptions filled at each sample and nonsample pharmacy, along with the geographic location of the pharmacy within the dispensing zone. Monte Carlo half-sample simulations are used to generate 95% confidence intervals (CIs) around these estimates (11). These estimates are accurate to within 5,578 per million prescriptions filled.

AdvancePCS

AdvancePCS is the oldest and largest pharmacy benefit management organization in the United States. Pharmacy benefit management organizations manage prescription drug benefits for large purchasers, negotiating medication discounts, processing drug claims, and implementing formularies to contain pharmaceutical expenditures (12).

Each year, AdvancePCS processes more than 450 million pharmacy claims and manages more than $18 billion in drug expenditures, representing 39% of the total U.S. pharmaceutical benefit management market (13). Whenever any AdvancePCS enrollee fills a prescription, the pharmacist enters the prescription data, which are transferred to AdvancePCS for authorization. Within 2 days of claim adjudication, these data are transferred to a central data warehouse, where a validity check is performed and patient information is de-identified.

Analytic Strategy

NDCHealth analyses

NDCHealth provided weekly national projections for psychotropic medication prescriptions collected nationally, in New York City, and in Washington, D.C. Because these data were only available as weekly averages rather than at the level of individual patients, they were used to provide a comprehensive overview of psychotropic medication use over time rather than for statistical analyses at the person level. Rates of prescriptions were tracked for four medication groups—antidepressant, antipsychotic/ antimania, anxiolytic, and hypnotic medications—which were categorized by using the First Data Bank classification system (14).

AdvancePCS analyses

AdvancePCS provided complete data for all prescriptions filled for psychotropic medications between September 2001 and December 2001, as well as data for September 2000 through December 2000. The protocol was approved as exempted from review by the Yale Institutional Review Board under regulation 45 CFR Part 46.101(b)(4). No identifiable, protected health information was available in the study data provided by AdvancePCS and NDCHealth.

The data set provided the name, national drug code, dosage of the medication, and date the prescription was filled, along with the patient’s age, sex, and three-digit zip code and a variable indicating whether an individual had obtained a prescription for that medication during the previous 365 days. Data on the urban/rural status of each three-digit zip code was obtained by merging this data with the area resource file (15). Four drug groups were created, again using the First Data Bank classification system: antidepressant, antipsychotic/antimanic, anxiolytic, and hypnotic medications (14). These data were analyzed at the level of the individual patient by using monthly totals for eligible members of AdvancePCS enrollees as a denominator for calculating rates of new prescriptions. Weekly estimates were inflated to account for federal holidays.

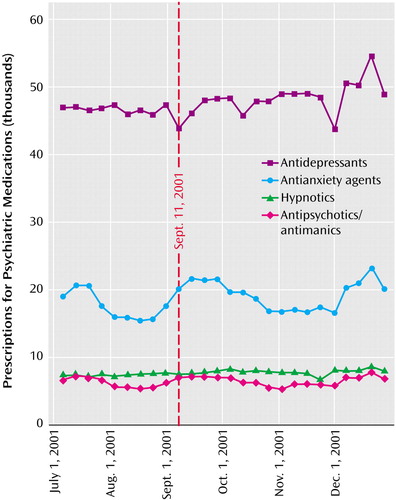

A first set of analyses examined weekly rates of use of new prescriptions during the 12 weeks after September 11, defined as the first prescription for that medication during the previous 365 days (Table 1). Analyses were also conducted for the New York City metropolitan region, in the zone 10 miles from the World Trade Center, and for the Washington, D.C., metropolitan region, in a 10-mile radius from the Pentagon. (This was the smallest geographic unit with adequate statistical power for the analyses.) To account for secular trends (16) and potential seasonal variation (17) in psychotropic prescribing, parallel analyses were performed for corresponding weeks during 2000, and findings were compared between the 2 years. Taylor series linearization generated standard errors for each of the rates by using the SUDAAN statistical software package, which were then used to compute z scores for comparing rates of new prescriptions before and after September 11 in each year as well as to compare the difference in rate ratios before and after September 11 between the years.

Next, a set of analyses assessed increases in average daily dose for psychoactive medications in the 12 weeks before and after September 11 nationally, in New York City, and in Washington, D.C., for 2000 and 2001 (Table 2). Daily dose was calculated by multiplying strength (i.e., milligrams) by the number of pills dispensed. Among those individuals with at least one prescription both before and after Sept. 11, analyses examined the proportion of individuals for whom the maximum dose of a particular psychotropic medication was higher in the 12 weeks after September 11, 2001, than in the 12 weeks before 2001. To examine whether these patterns were temporally related to the 2001 terrorist attacks, a parallel set of analyses was conducted of dose increases during the 12 weeks following Sept. 11, 2000. Chi-square tests were used to examine whether the rate of dose increases in 2001 differed significantly from the rate of dose increases in 2000. Separate analyses were conducted among users of each drug class. Then, to examine potential differences across key patient and demographic variables, analyses for total psychoactive medication use were conducted, stratified by age (<18, 18–64, >64), gender, region (Northeast, Midwest, South, West), and urban/rural status. These analyses were conducted in SAS.

Results

Total Prescriptions

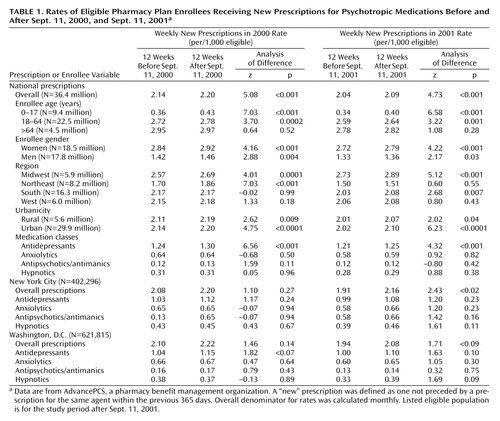

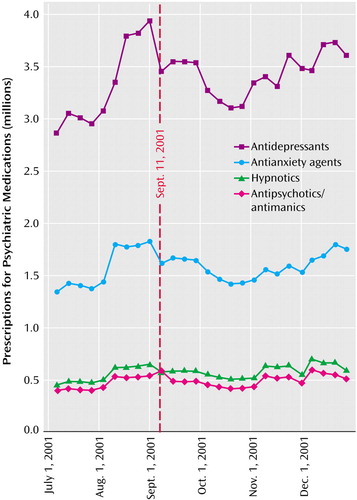

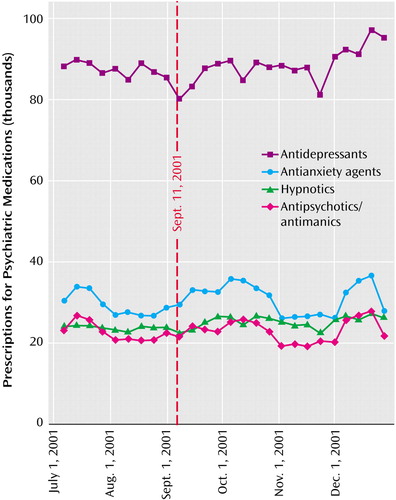

An estimated 156.9 million prescriptions for psychoactive medications were filled nationwide from July through December 2001 based on NDCHealth projections (Figure 1, Figure 2, and Figure 3). Aside from a small decline during the week of September 11, the total number of weekly prescriptions for all four medication classes remained relatively stable during the period after the September 11 attacks in the United States, New York City, and Washington, D.C. (Figure 1, Figure 2, and Figure 3).

The average monthly number of enrollees in the AdvancePCS data set during the study period was 34.0 million in 2000 and 36.4 million in 2001. During 2001, a total of 1.5 million individuals, or 4.1% of the enrolled population, had one or more prescriptions for a psychotropic medication.

Rates of Enrollees With New Prescriptions

The overall rate of use of new psychotropic medications increased after Sept. 11, 2001, from 2.04 to 2.09 prescriptions per 1,000 enrollees (relative risk=1.03, 95% CI=1.02–1.03) (Table 1). However, this increase was nearly identical to that seen during the same weeks in 2000 (relative risk=1.03, 95% CI=1.02–1.03). The z test for difference between the two relative risks was nonsignificant (z=0.56, p=0.57), suggesting that this increase represented a seasonal effect (present in both years) rather than an increase related to the terrorist attacks. This pattern was consistent across all of the strata examined. Washington, D.C., also did not demonstrate an increase in new prescriptions after the terrorist attacks (difference in relative risks between 2000 and 2001, z=–1.32, p=0.18).

Residents of New York City had a somewhat larger (1.13 times) increase in new prescriptions (relative risk=1.13, 95% CI=1.07–1.19). Although this increase was about twice the magnitude of that seen after September 2000 (relative risk=1.06, 95% CI=1.00–1.11), the difference between the two relative risks was not statistically significant (z=–1.84, p<0.07).

Proportion of Treated Enrollees With Dose Increases

Nationally, a total of 13.0% of enrollees taking psychotropic medications had a dose increase in the 12 weeks after Sept. 11, 2001, a small but significant decline relative to the proportion of enrollees who had a dose increase during the previous year (13.0% versus 13.4%) (χ2=8.5, df=1, p=0.004). The only group nationally for which there was a substantial rise in dose increases was enrollees taking antipsychotic medications, 18.7% of whom had dose increases in 2001 compared with the 17.1% who had dose increases in 2000 (χ2=3.8, df=1, p<0.05). Washington, D.C., had similar patterns to those seen nationally, with nonsignificant tendencies toward lower rates of dose increases across all four medication classes (Table 2).

In New York, the pattern of dose increases was the opposite of that seen nationwide and in Washington, D.C. Individuals in treatment with psychotropic medication were significantly more likely to have a dose increase between the 12 weeks before and after Sept. 11, 2001, than between the same weeks in 2000 (16.9% versus 13.6%) (χ2=6.5, df=1, p=0.01). This change reflected a significant increase in the proportion of individuals treated with antidepressants with dose elevations (17.1% versus 13.7%) (χ2=4.3, df=1, p<0.04), and nonsignificant tendencies toward increases in higher doses for those treated with anxiolytic and hypnotic medications.

Discussion

In the general population, the acute shock and fear of the events of September 11 were not accompanied by a commensurate increase in the use of psychotropic medications. However, for certain subpopulations—in particular, certain subgroups of patients already taking psychotropic medications—there was a small but consistent increase in the use of these medications. Understanding Americans’ help-seeking behavior after these events thus requires a consideration of each of these findings—both the general lack of an increase in use among Americans as a whole and the factors conferring vulnerability to those subgroups.

The current study’s findings confirm and expand on earlier reports finding little or no increase in the use of formal mental health services after the attacks. Those studies found no increase in managed behavioral health care (18), military (19), or U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs (20) mental health service use, even among patients with preexisting PTSD and other mental conditions (21). A study of prescriptions filled by employees of two companies found a transient increase in the use of antianxiety medications but not for other categories of psychotropic drugs in the weeks following the attacks (22).

Taken together, this evidence suggests that initial predictions of a drastic increase in mental health service use after September 11 were not realized. There are several possible explanations for this negative finding. First, it is possible that patients who needed care failed to obtain access to it. The weeks after September 11 were followed by an unprecedented infusion of public and private funds for mental health treatment, as well as campaigns encouraging the public to use those resources (23, 24). However, other barriers, including stigma, lack of insurance coverage, or the chaos imposed by the events of September 11 themselves, may have prevented individuals from obtaining needed services.

Second, it is possible that many individuals, while symptomatic, did not see themselves as needing formal mental health treatment. A decision to seek mental health services, or any health services, typically involves not only symptoms but also the perception that they are a problem that requires treatment (25). In the aftermath of the terrorist attacks, many Americans may have regarded their distress as a “normal” reaction to these unprecedented events that was shared with their neighbors and communities rather than as a disorder needing care.

Finally, many people are likely to have sought help through friends and family, local communities, or clergy. These informal services, along with debriefing and counseling services specifically put in place after the September 11 attacks (e.g., New York’s Project Liberty), would not be captured in claims databases.

Nationally, the only group with an increase in psychotropic prescriptions after the September 11 attacks was patients already being treated with antipsychotic medications. This is consistent with previous research indicating the psychological vulnerability conferred by preexisting psychiatric disorders after traumatic events. More than half of the individuals with PTSD resulting from the Oklahoma City bombing met criteria for a psychiatric disorder before the incident (26), and the presence of a preexisting diagnosis of a mental disorder was a strong predictor of attack-related distress after Sept. 11, 2001 (27, 28). Indeed, the presence of a preexisting psychiatric disorder is one of the factors most consistently found to predict PTSD after traumatic events (29, 30). Patients with schizophrenia and other psychotic disorders may be the most vulnerable group of all; even minor stressors may be enough to lead to exacerbations in this population (31).

In New York, a modest but consistent increase in dose was seen among existing users of psychotropic medications. This finding is consistent with epidemiological reports that the degree of attack-related distress was inversely proportional to the distance from where the attack occurred (1, 4). New Yorkers were more likely than the rest of the nation either to be directly involved in the attacks or to have family, friends, or acquaintances who were affected. In contrast, most Americans who lived outside of New York City primarily experienced the attacks indirectly. Vicarious exposure to traumatic events, while stressful, may differ both quantitatively and qualitatively from more direct forms of trauma (32).

The study’s findings should be interpreted in the context of several important limitations. The data sets had considerably more breadth than depth; they did not include mental health diagnoses, other important clinical data, or information on treatments other than pharmacotherapy. Second, some individuals might have had delayed onset of symptoms or treatment-seeking that did not emerge until after the 3-month follow-up period. Clinically, such delayed responses appear to be relatively rare (26, 33). Methodologically, it would be difficult to establish whether any changes in psychotropic medication occurring after the first several months had any causal connection to the terrorist attacks.

The study’s findings are consistent with epidemiological surveys indicating that the distress associated with the September 11 attacks was more transient and self-limited than had originally been anticipated. Nationally, the proportion of the population reporting depressive symptoms fell by more than half by the beginning of November 2001 (34), and most PTSD symptoms in New York City residents had resolved by 6 months after the attacks (35). This apparent resilience may have been possible not so much in spite of, but rather because of, the breadth of their impact. Following the September 11 attacks, Americans reported an increased sense of connectedness to each other and their nation which was marked by rising volunteerism, greater involvement in local organizations, and a surge of patriotism (36). Such a sense of community can provide a powerful healing force; for Americans, it may have helped provide a context for, and a means of coping with, the terrorist attacks.

|

|

Received Oct. 1, 2003; revision received Nov. 21, 2003; accepted Dec. 17, 2003. From the Rollins School of Public Health, Emory University; and the University of Pennsylvania School of Social Work, Philadelphia. Address reprint requests to Dr. Druss, 1518 Clifton Rd. N.E., Room 606, Atlanta, GA 30322; [email protected] (e-mail). Funded in part by NIMH grant K08-MH-01556-01A. The authors thank Duane McKinley and Heather Haupert of AdvancePCS and Randy Carpio from NDCHealth for their support and technical assistance.

Figure 1. Prescriptions for Psychotropic Medications Before and After Sept. 11, 2001, in the United Statesa

aData were supplied by NDCHealth, a health care information service company, and represent NDCHealth national projections for psychotropic medication prescriptions. Point estimates for antidepressants and anxiolytics are ±0.56%; point estimates for antipsychotics and hypnotics are ±0.81%.

Figure 2. Prescriptions for Psychotropic Medications Before and After Sept. 11, 2001, in the New York Metropolitan Regiona

aData were supplied by NDCHealth, a health care information service company, and represent NDCHealth projections for psychotropic medication prescriptions in the New York City region (all zip codes within a 10-mile radius of the World Trade Centers). Point estimate for antidepressants is ±1.95%; point estimates for anxiolytics, antipsychotics, and hypnotics are ±3.39%.

Figure 3. Prescriptions for Psychotropic Medications Before and After Sept. 11, 2001, in the Washington, D.C., Areaa

aData were supplied by NDCHealth, a health care information service company, and represent NDCHealth projections for psychotropic medication prescriptions in the Washington, D.C., region (all zip codes within a 10-mile radius of the Pentagon). Point estimate for antidepressants is ±2.62%, point estimate for anxiolytics is ±4.15%; point estimates for hypnotics and antipsychotics are ±6.2%.

1. Schuster MA, Stein BD, Jaycox L, Collins RL, Marshall GN, Elliott MN, Zhou AJ, Kanouse DE, Morrison JL, Berry SH: A national survey of stress reactions after the September 11, 2001, terrorist attacks. N Engl J Med 2001; 345:1507–1512Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

2. Pew Research Center for the People and the Press: American Psyche Reeling From Terror Attacks. Pew Research Center Report, Sept 19, 2001. http://people-press.org/reports/display. php3?ReportID=3Google Scholar

3. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention: psychological and emotional effects of the September 11 attacks on the World Trade Center—Connecticut, New Jersey, and New York, 2001. JAMA 2002; 288:1467–1468Medline, Google Scholar

4. Schlenger WE, Caddel JM, Ebert L, Jordan BK, Rourke KM, Wilson D, Thalji L, Dennis JM, Fairbank JA, Kulka RA: Psychological reactions to terrorist attacks: findings from the national study of Americans’ reactions to September 11th. JAMA 2002; 288:581–588Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

5. Galea S, Resnick H, Ahern J, Gold J, Bucuvalas M, Kilpatrick D, Stuber J, Vlahov D: Posttraumatic stress disorder in Manhattan, New York City, after the September 11th attacks. J Urban Health 2002; 79:340–353Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

6. Simeon D, Greenberg J, Knutelska M, Schmeidler J, Hollander E: Peritraumatic reactions associated with the World Trade Center Disaster. Am J Psychiatry 2003; 160:1702–1705Link, Google Scholar

7. Galea S, Ahern J, Resnick H, Kilpatrick D, Bucuvalas M, Gold J, Vlahov D: Psychological sequelae of the September 11 terrorist attacks in New York City. N Engl J Med 2002; 346:982–987Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

8. Vlahov D, Galea S, Resnick H, Ahern J, Boscarino JA, Bucuvalas M, Gold J, Kilpatrick D: Increased use of cigarettes, alcohol, and marijuana among Manhattan, New York, residents after the September 11th terrorist attacks. Am J Epidemiol 2002; 155:988–996Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

9. Herman D, Felton C, Susser E: Mental health needs in New York State following the September 11th attacks. J Urban Health 2002; 79:322–331Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

10. Gilbert C: Thompson worries over post-traumatic stress. Milwaukee Journal Sentinel, Sept 21, 2001, p 13AGoogle Scholar

11. NDCHealth: Projection Methodology Overview. Atlanta, NDCHealth, 2002Google Scholar

12. US General Accounting Office: Effects of Using Pharmacy Benefit Managers on Health Plans, Enrollees, and Pharmacies: GAO-03–196, Jan 2003. http://www.gao.gov/new.items/d03196.pdfGoogle Scholar

13. PriceWaterhouseCoopers LLP: HCFA Study of the Pharmaceutical Benefit Management Industry, June 2001. www.cms.gov/ researchers/reports/2001/cms.pdfGoogle Scholar

14. National drug data file. San Bruno, Calif, First Data Bank, 1996Google Scholar

15. Bureau of Health Professions, Office of Research and Planning: Area Resource File. Fairfax, Va, Quality Resource Systems, 2000Google Scholar

16. Pincus HA, Tanielian TL, Marcus SC, Olfson M, Zarin DA, Thompson J, Magno Zito J: Prescribing trends in psychotropic medications: primary care, psychiatry, and other medical specialties. JAMA 1998; 279:526–531Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

17. Tansella M, Micciolo R: Trends in the prescription of antidepressants in urban and rural general practices. J Affect Disord 1992; 24:117–125Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

18. Goldman W: Terrorism and mental health: private sector responses and issues for policy makers. Psychiatr Serv 2002; 53:941–943Link, Google Scholar

19. Hoge CW, Pavlin JA, Milliken CS: Psychological sequelae of September 11. N Engl J Med 2002; 347:443–445Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

20. Rosenheck R: Reactions to the events of September 11. N Engl J Med 2002; 346:629–630Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

21. Rosenheck R, Fontana A: Use of mental health services by veterans with PTSD after the terrorist attacks of September 11. Am J Psychiatry 2003; 160:1684–1690Link, Google Scholar

22. McCarter L, Goldman W: Psychopharmacology: use of psychotropics in two employee groups directly affected by the events of September 11. Psychiatr Serv 2002; 53:1366–1368Link, Google Scholar

23. Strom S: Finding a cure for hearts broken on September 11 is as difficult as explaining the cost. New York Times, July 22, 2002, p B1Google Scholar

24. Goode E: Program to cover psychiatric help for 9/11 families. New York Times, Aug 21, 2002, p 1Google Scholar

25. Mojtabai R, Olfson M, Mechanic D: Perceived need and help-seeking in adults with mood, anxiety, or substance use disorders. Arch Gen Psychiatry 2002; 59:77–84Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

26. North CS: Psychiatric disorders among survivors of the Oklahoma City bombing. JAMA 1999; 282:755–762Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

27. Silver RC, Holman EA, McIntosh DN, Poulin M, Gil-Rivas V: Nationwide longitudinal study of psychological responses to September 11. JAMA 2002; 288:1235–1244Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

28. Franklin CL, Young D, Zimmerman M: Psychiatric patients’ vulnerability in the wake of the September 11th attacks. J Nerv Ment Dis 2002; 190:833–837Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

29. Breslau N: Epidemiological studies of trauma, posttraumatic stress disorder, and other psychiatric disorders. Can J Psychiatry 2002; 47:923–929Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

30. Brewin CR, Andrews B, Valentine JD: Meta-analysis of risk factors for posttraumatic stress disorder in trauma-exposed adults. J Consult Clin Psychol 2000; 68:748–766Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

31. Nuechterlein KH, Dawson ME, Gitlin M, Ventura J, Goldstein MJ, Snyder KS, Yee CM, Mintz J: Developmental processes in schizophrenic disorders: longitudinal studies of vulnerability and stress. Schizophr Bull 1992; 18:387–425Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

32. North CS, Pfefferbaum B: Research on the mental health effects of terrorism. JAMA 2002; 288:633–636Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

33. North CS: The course of post-traumatic stress disorder after the Oklahoma City bombing. Mil Med 2001; 166(12 suppl):51–52Google Scholar

34. Pew Research Center for the People and the Press: Worries About Terrorism Subside in Mid-America, Nov 8, 2001. http://people-press.org/reports/display.php3?ReportID=142Google Scholar

35. Galea S, Vlahof D, Resnick H, Ahern J, Susser E, Gold J, Bucuvalas M, Kilpatrick D: Trends of probable post-traumatic stress disorder in New York City after the September 11 terrorist attacks. Am J Epidemiol 2003; 158:514–524Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

36. Putnam RD: Bowling Together. The American Prospect, Feb 11, 2002. www.prospect.orgGoogle Scholar