A Randomized, Placebo-Controlled Trial of Sertraline for Prophylactic Treatment of Highly Recurrent Major Depressive Disorder

Abstract

OBJECTIVE: Previous antidepressant maintenance trials have used the same medication from acute through maintenance phases, confounding the interpretation of prophylactic effects. The purpose of this study was to determine whether sertraline prevents the recurrence of major depressive disorder among patients with recurrent depression who had been treated to remission with medications other than sertraline. METHOD: Patients who had experienced at least three documented episodes of major depressive disorder within the last 4 years and who were currently in full remission were eligible. The last episode must have been treated for at least 4 months with any antidepressant except sertraline. For the initial single-blind placebo lead-in phase, 371 patients were included; 288 were included in the analyses for the 18-month double-blind phase in which patients were randomly assigned to sertraline (50 or 100 mg) or placebo (two capsules per day). Recurrence was defined as a depressive episode that fulfilled DSM-IV criteria or the appearance of symptoms that required the administration of another antidepressant treatment. RESULTS: Sixty-one patients discontinued before the double-blind phase, including 33 who experienced a relapse. Out of the 288 who entered the double-blind prophylactic phase, 123 discontinued, including 65 for recurrences. Recurrences were significantly lower in the sertraline groups compared with placebo (sertraline, 50 mg: 16 [16.8%] of 95; sertraline, 100 mg: 16 [17.0%] of 94; placebo: 33 [33.3%] of 99). Patients treated with sertraline also had a significantly longer time until recurrence compared with placebo-treated patients. CONCLUSIONS: Among remitted patients with a history of multiple depressive episodes, sertraline at a dose of either 50 or 100 mg/day prevented recurrences significantly more than did placebo.

Approximately 17% of individuals will experience an episode of major depressive disorder in their lifetime (1). The prevalence of this disorder, together with associated impairments in work and social functioning (2–4), has led to the identification of depression as the fourth most disabling illness in the world (5). Compounding the public health significance of depression is the highly recurrent nature of the disorder. Of those individuals with an episode of major depressive disorder, a recent study indicates that 41% will have a second episode within a year, 59% within 2 years, and 74% within 5 years (6).

The treatment of depression is commonly divided into three distinct phases (7). The acute phase begins with the initial presentation of an episode and is designed to elicit at least a response as determined by a clinically significant reduction in symptoms. This is followed by a continuation phase designed to prevent a relapse of the most recent episode. Continuation therapy of at least 6 months is now recommended (8, 9). Complete symptom remission can occur in either the acute or continuation phase, and full recovery is defined as a sustained period of remission lasting several months. The final phase is maintenance treatment, which has as its goal the prevention of a new acute episode (a recurrence) of major depressive disorder. Maintenance treatment has specifically been recommended for any patient who has had three or more major depressive episodes in the past 5 years (8, 10).

A number of placebo-controlled or comparative trials have provided evidence of maintenance efficacy for antidepressant agents. Agents tested in these trials include imipramine (11), desipramine (12), phenelzine (13), sertraline (14, 15), fluoxetine (16), paroxetine (17), and citalopram (18). In all of these trials, however, only responders to the drug utilized during the acute phase were included in the maintenance trial. This design has been described as introducing a potentially significant selection bias that limits the generalizability of results (19). In these studies, prevention findings are only relevant to the population of patients who are highly responsive to the study medication during the acute phase, rather than the broader group of patients achieving remission of their major depressive disorder through various approaches, i.e., other antidepressants or combination therapies. To overcome this selection bias, maintenance medication should be evaluated among patients achieving initial remission through other means besides the maintenance agent.

A second problem with previous maintenance studies is the difficulty in distinguishing relapse from recurrence. Because recurrence refers to the development of a new episode, it can only occur after recovery from the previous episode. However, the time periods that have been proposed to define continuation treatment for relapse prevention versus maintenance treatment for recurrence prevention do not have an empirical basis (20). When patients remain on the same medication throughout acute and continuation treatment, it is not possible to know whether patients have actually recovered from their initial episode or whether the medication is simply suppressing the symptoms of the original episode, which would rapidly return if medication was discontinued. To be certain that a full recovery has occurred, patients would need to be withdrawn from the original treatment and monitored for a period of time to determine if remission is stable. Although the use of a no-treatment phase to determine whether full recovery is evident has been recommended (20), no previous antidepressant maintenance trials have incorporated this design feature to determine whether stable remission has actually occurred.

The present study was designed specifically to address these methodological concerns with previous studies and to evaluate the prophylactic efficacy and safety of the antidepressant sertraline, a selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor, compared with placebo in patients with highly recurrent major depressive disorder. We hypothesized that sertraline would result in a lower recurrence rate and a longer time until recurrence than placebo.

Method

Patients

Male or female outpatients over 18 years of age with major depressive disorder, recurrent subtype, were recruited at 83 psychiatric centers in France during the period from Aug. 16, 1995, to Nov. 8, 1999. To be eligible, patients must have had at least three episodes of major depressive disorder in the 4 years preceding the study, as determined by systematic review of clinical records over the 4-year period. The most recent episode had to occur within 6 months of entry into the study. Treatment for this episode consisted of any antidepressant except sertraline. Among the patients judged as successfully treated by the investigator, those who were in remission at the selection visit were eligible for entry in the study. Remission was defined as meeting all of the following criteria: 1) absence of “depressed mood” and “markedly diminished interest” according to DSM-IV, 2) presence of no more than two of the seven other DSM-IV symptom criteria for major depressive episode, and 3) a maximum score of 2 for the sum of the first two items of the Montgomery-Åsberg Depression Rating Scale (21) (“apparent and reported sadness”). The previous treatment could not have been discontinued for more than 2 of the previous 6 months at the time of study entry.

Patients were excluded if they had another current psychiatric disorder (including comorbid anxiety disorder) or a prior history of schizophrenia, psychotic disorder, or bipolar disorder. Patients were also excluded if they had a prior history of alcoholism or drug dependency, were considered at high risk for suicide, or had any emotional/intellectual problem that could invalidate the patient’s consent or limit ability to comply with the protocol.

Women of childbearing potential had to agree to use appropriate contraception during the trial. Treatment with any other antidepressant agent, alprazolam (which has a potential antidepressant effect), any antipsychotic medication, or psychotherapy was not allowed during the course of the study. All the anxiolytic treatments prescribed during the last episode of depression were to be withdrawn or the dose reduced to the maximum of 10 mg in diazepam equivalents.

Study Design

This was a randomized two-phase study with a total duration of 20 months. Phase I was a 2-month, single-blind placebo period designed to confirm that the remission was stable and that the patient was in full recovery. Patients entered phase I of the study immediately after the successful treatment (i.e., remission as defined earlier) of their previous depressive episode. During this phase, patients received two capsules of placebo per day taken at the same time each day.

Those patients who continued to remain in remission over the course of phase I, and continued to meet inclusion/exclusion criteria at the end of phase I, entered into the recurrence prevention phase. This phase II was a double-blind treatment period lasting 18 months (day 60 to month 20) in which patients were randomly assigned to one of three groups: placebo (two capsules per day); sertraline, 50 mg/day (one 50-mg capsule of sertraline and one placebo capsule); or sertraline, 100 mg/day (two 50-mg capsules of sertraline after a 15-day period of sertraline, 50 mg/day [with one placebo capsule]). All capsules were taken at the same time each day (bedtime). No increase or reduction in dose was permitted during the study. Study investigators were all psychiatrists in community or hospital settings.

Randomization was stratified by center, in blocks of three, and was performed according to a central computerized randomization schedule. Once the centralization random assignment was generated, each center distributed the therapeutic units on a chronological basis.

The study was conducted in accordance with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki and its amendments. In addition, the study followed European Community Good Clinical Practice and French regulations for the conduct of clinical trials. The study protocol and the amendments were approved by an appropriate local ethics review committee (Comité Consultatif pour la Protection des Personnes se prêtant à une Recherche Biomédicale). Written informed consent was obtained from each patient before participating in the study. According to ethical and legal considerations, all identifying information concerning the patients has been avoided.

Efficacy Assessments

The primary efficacy criterion was the occurrence of a new depressive episode (recurrence) during the 18-month double-blind phase II treatment period. At each visit during phase II, the clinical investigator evaluated whether the patient was experiencing a recurrence by using a semistructured interview that was guided by a DSM-IV checklist containing the criteria for major depressive disorder (with the exception that the temporal criterion was not applied). Investigators were trained in the use of this instrument and diagnostic criteria for major depressive disorder at a meeting before commencement of the study. Secondary outcomes were also assessed at each visit with the clinician-rated Montgomery-Åsberg Depression Rating Scale (21) and Clinical Global Impression (CGI) scales for improvement and severity (22). Assessments were conducted at the beginning of phase I (selection visit), the beginning of phase II (randomization visit), and at months 4, 5, 8, 11, 14, 17, and 20, as timed from entry into phase I. Investigators were kept blind to treatment assignment.

Recurrence was defined in two ways: 1) meeting DSM-IV criteria for a major depressive episode as determined by the DSM-IV checklist or 2) the appearance of symptoms which, in the opinion of the clinician, required the administration of another antidepressant treatment. This second definition was designed to capture probable recurrences that may not have yet fully met DSM-IV criteria. However, the final decision about whether a recurrence occurred was based upon an independent review of all patient data by a Scientific Committee blind to the clinician’s decision and to treatment assignment. Two patients were moved from one classification to another. One patient classified as experiencing “no recurrence” by a clinician was reclassified as having experienced a “recurrence” by the End-Point Review Committee; one patient classified as experiencing a “recurrence” by a clinician was reclassified as having experienced “no recurrence.” Four noninvestigator psychiatrists attended this committee.

Safety Assessments

All observed or volunteered adverse events, including adverse drug reactions, illnesses with onset during the course of treatment, and exacerbations of preexisting illnesses, were recorded at each visit.

Statistical Analysis

The comparability of the treatment groups at randomization was assessed by using a one-way analysis of variance, and qualitative data were compared with the chi-square test or Fisher’s exact test.

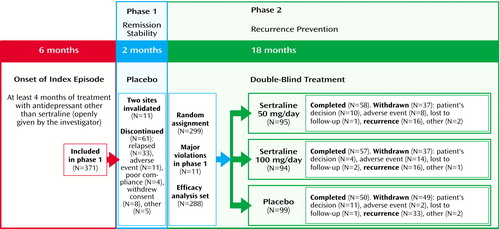

The primary criterion for efficacy, defined a priori, was the percentage of patients treated with sertraline versus placebo who experienced recurrence. Recurrence rates for the two sertraline groups (pooled) were compared with placebo by using the chi-square test, with alpha set to 0.05. If significant, this analysis was followed by pairwise comparisons of the three treatment groups using a Bonferroni-corrected alpha of 0.0167 (0.05/3).

Time to recurrence was examined using nonparametric Kaplan-Meier survival curves and the log-rank test, and the pooled sertraline group was compared with the placebo group. If this comparison was significant, pairwise comparisons with a Bonferroni-corrected alpha of 0.0167 were examined. Secondary analyses examined the effects of covariates on recurrence rates using Cox proportional hazards regression models.

Safety analyses were conducted using Fisher’s exact test for each pairwise comparison of the treatment groups in the incidence of adverse events, with significance declared at p<0.05. All statistical tests were two-tailed.

Results

Patient Disposition

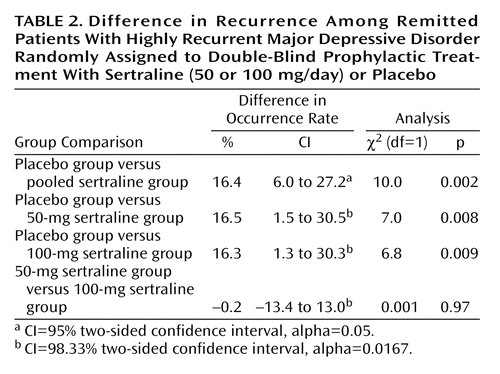

Figure 1 summarizes the progression of the patients through the two phases of the trial. Sixty-one patients (16.4%) discontinued during phase I, including 33 patients (8.9%) who experienced a relapse. Eleven additional patients from two invalidated centers were excluded from further analysis (one center relocated without informing the research team, and the investigator at the second center stopped the study and influenced his patients to withdraw consent). During phase II, 123 patients (41.1%) discontinued, including 65 patients (21.7%) who suffered a recurrence.

Patient Characteristics

Of 299 patients randomly assigned to a treatment condition, 11 had major protocol violations during phase I and were not reassessed by the Scientific Committee. Consequently, 288 patients were included in the primary efficacy analysis, and their characteristics are shown in Table 1. No statistically significant differences were observed between the three treatment groups with regard to demographic data, depression history, Montgomery-Åsberg Depression Rating Scale score, or CGI severity or improvement ratings at randomization. Before entering the single-blind wash-out period, 73% of patients were taking psychotropic medications (the most frequently prescribed antidepressants were fluoxetine [N=118], paroxetine [N=124], clomipramine [N=102], and citalopram [N=48]). Concomitant medications were recorded at each visit. At randomization, 21.2% of patients were taking benzodiazepines. The percentage of patients who received psychotropics and benzodiazepines was not statistically different in the sertraline and placebo groups. These percentages slightly decreased throughout the study in the three groups.

Compliance

Treatment compliance (measured by examination of the capsule blister packs) was between 98.5% and 100%.

Incidence of Recurrence

Over the course of the 18-month study, a new depressive episode was recorded in 33.3% of patients in the placebo group and in 16.9% of those who received sertraline (Table 2). No statistically significant difference was observed in the incidence of recurrence between the 50-mg sertraline group and the 100-mg sertraline group (16.8% and 17.0%, respectively). Similar results were obtained when the 11 patients with major violations from phase I were included in the analysis (placebo: 34%; sertraline, 50 mg: 16.3%; sertraline, 100 mg: 16.3%).

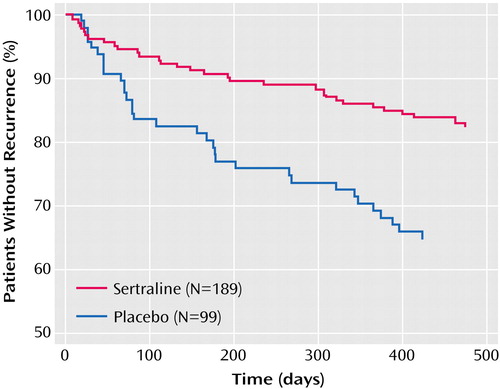

Time to Recurrence

Time-to-event analysis revealed that new depressive episodes occurred during the entire course of the 18-month study in all treatment groups. At each time point, the recurrence rate was always higher in the placebo group than in the sertraline groups (Figure 2). Significant differences were observed between the placebo and combined sertraline groups (log-rank test=10.6, p=0.001), placebo and 50-mg sertraline groups (log-rank test=7.9, p=0.005), and placebo and 100-mg sertraline groups (log-rank test=6.2, p<0.02) but not between the 50- and 100-mg sertraline groups (log-rank test=0.04, p=0.84).

Effects of Clinical and Demographic Covariates on Time to Recurrence

The influence of a number of clinical and demographic factors on time to recurrence was examined by using Cox proportional hazards models. Factors examined included Montgomery-Åsberg Depression Rating Scale score, CGI severity rating, number of DSM-IV criteria present at randomization, previous history of depression, class of previous antidepressant, and demographic characteristics. None of the factors had a significant effect on recurrence rate.

Safety

Safety was examined in all 299 patients (including the 11 patients with protocol violations during phase I). A slightly greater proportion of patients in the 100-mg sertraline group (80%) experienced adverse events compared with the 50-mg sertraline (76%) and placebo (71%) groups. The majority of adverse events were rated as mild (47%) or moderate (42%), classified as not related to study treatment (71%), and resolved at study end (94%). Only 9% of adverse events led to treatment discontinuation. A significantly greater proportion of patients in the 100-mg sertraline group (15.3% [N=15 of 98]) relative to placebo (1.9% [N=2 of 103]) discontinued treatment because of adverse events (p=0.0006, Fisher’s exact test). The proportion of patients in the 50-mg sertraline group that discontinued treatment because of adverse events (9.2% [N=9 of 98]) was not significantly different from placebo (p=0.054, Fisher’s exact test).

The most frequently reported adverse events were anxiety, influenza-like symptoms, and insomnia (Table 3). In pairwise comparisons of the three treatment groups, there were no significant differences in the rates of any adverse events.

A total of 26 serious adverse events were reported in 20 patients (placebo group: N=6; 50-mg sertraline group: N=5; 100-mg sertraline group: N=9). No serious adverse event was classified as related to study treatment. One death by drowning, an apparent suicide, occurred in a patient in the 100-mg sertraline group, 11 days after her 3-month visit. There were no signs of drug overdose.

Discussion

The results of the current study provide evidence of the prophylactic efficacy of sertraline treatment in a high-risk sample of patients who had suffered from at least three depressive episodes in the previous 4 years. The relative risk of recurrence of major depression after treatment with sertraline was approximately half that observed with placebo. No significant differences were observed in the incidence of recurrence between the 50-mg and 100-mg sertraline groups, suggesting that a sertraline dose of 50 mg appears to be sufficient to prevent recurrence.

Many controlled trials have reported the efficacy of various antidepressants in sustaining response beyond the first 6–10 weeks of acute treatment and in preventing relapse during 4–12 months of “continuation” therapy. The long-term efficacy results of such designs are confounded, however, by a selection bias that limits the long-term treatment study sample to patients who are responders to acute treatment with the drug under study. In other words, typical maintenance treatment studies are not true studies of prophylactic efficacy, but instead evaluate, in a more limited way, the ability of a drug to sustain its initial response and only in the subgroup of patients responding to the same antidepressant drug.

The current study, however, avoided the selection bias associated with such a response-contingent entry criterion by recruiting patients who had not achieved a response due to treatment with sertraline. More important, enrollment was contingent not only on achieving episode remission but also on maintaining remission while not receiving any antidepressant treatment. As a consequence, the study was designed as a pure test of prophylactic efficacy in a high-risk sample. This approach represents a new model to evaluate any compound in the prevention of depressive recurrence.

Overall, the rates of recurrence of major depressive disorder were relatively low during maintenance treatment. This may have been due to the long (2-month) single-blind placebo phase I period. Some patients with a high proneness for a recurrence may have discontinued during phase I, thereby lowering the potential recurrence rates during phase II. It is possible also that repeated contact with mental health professionals during study visits may have contributed to the relatively low recurrence rate observed. Last, a longer period of the study might have increased the number of recurrences.

None of the clinical or demographic variables examined were found to significantly influence the time to recurrence. Of particular note is that in this patient cohort with highly recurrent depression, the number of previous episodes did not appear to affect the rate of recurrence.

One of the potential clinical implications of the current trial is that patients who report three or more previous depressive episodes—but who are currently in remission and no longer taking medication—might benefit from starting prophylactic treatment with sertraline. The evidence from the current study suggests that such prophylactic treatment will reduce by more than twofold the recurrence risk over the next 18 months. This result must be confirmed by further research in high-risk samples treated for longer time periods.

A substantial proportion of patients who received placebo still remained free of recurrence over the 18-month study period.

Overall, prophylactic treatment with sertraline was well tolerated, with no differences between sertraline and placebo in the incidence of adverse events. The majority of adverse events were not serious, were rated as mild or moderate, were not related to study treatment, and resolved at the end of the study. The incidence of specific adverse events with sertraline were generally lower in the current trial compared with a previous maintenance trial that enrolled patients treated during acute and continuation therapy with sertraline (14). Further research is needed to clarify whether recovered patients with a history of recurrent depression who begin a course of sertraline for prophylactic purposes are less susceptible to adverse events compared with nonrecovered patients or patients treated continuously with sertraline from the presentation of an index episode of major depressive disorder.

Some limitations of this study should be noted. First, the study was not designed to determine the optimum length of time to prevent recurrence. Second, we do not know if the population of patients assessed in the study, presenting with multiple episodes of depression, corresponded to the true “real-life” at-risk population among depressed patients who should receive prophylactic treatment. The restrictive nature of the inclusion/exclusion criteria may limit the generalizability of the findings.

In summary, the results of this study indicate that sertraline has significant efficacy for the prevention of depression recurrence among patients with a history of prior episodes, even in patients who have achieved stable euthymia and are not receiving medication. If confirmed by further research, the significant prophylactic efficacy of sertraline in at-risk patients who are well has potentially important implications for the long-term management of depression. The current study is the first to demonstrate a preventive effect for an antidepressant medication among patients who were both treated to remission using other agents and maintained their remission without medication.

Acknowledgments

Patient enrollment for the PREVERS (PREVEntion of Recurrences with Sertraline) study was conducted by the following 83 investigators: Dr. Amar, Dr. Aspe, Dr. Audet, Dr. Autheman, Dr. Azra, Dr. Baranovsky, Dr. Bensimon, Dr. Bensoussan, Dr. Berthet, Dr. Bocher, Dr. Bonnafoux, Dr. Bonnan, Dr. Caillard, Dr. Cannat, Dr. Cazalot, Dr. Charrier, Dr. Chaumont, Dr. Choquet, Dr. Corbin, Dr. Cournac, Dr. Cyran, Dr. Dabert, Dr. Danan, Dr. Delance, Dr. Dilouya, Dr. Druot, Dr. Ducher, Dr. Engel, Dr. Estrabol, Dr. Faruch, Dr. Faure, Dr. Ferriere, Dr. Gailledreau, Dr. Geraud, Dr. Gheysen, Dr. Gozlan, Dr. Hanus, Dr. Henry, Dr. Hervé, Dr. Hourde, Dr. Jouan, Dr. Kalck-Stern, Dr. Katz, Dr. Kurc, Dr. Langeard, Dr. Lanvin, Dr. Leaustic, Dr. Leclercq, Dr. Legoubey, Dr. Leibovici, Dr. Louvrier, Dr. Magnan, Dr. Maloux, Dr. Mechert, Dr. Mennessier, Dr. Mermberg, Dr. Moles, Dr. Mouhot, Dr. Mouton, Dr. Osier, Dr. Pargade, Dr. Pon, Dr. Quemere, Dr. Quenard, Dr. Raab, Dr. Rance, Dr. Rigaud, Dr. Rustan, Dr. Sala-Rolland, Dr. Salfati, Dr. Savajols, Dr. Schlecht, Dr. Simon, Dr. Singer, Dr. Sontag, Dr. Tastevin, Dr. Tedo, Dr. Thorpe, Dr. Vaillant, Dr. Vanier, Dr. Vigara, Dr. Villatte, Dr. Zins-Ritter.

|

|

|

Received Nov. 25, 2002; revision received July 28, 2003; accepted Aug. 28, 2003. From the Hôpital Fernand Widal, Assistance Publique Hôpitaux de Paris; Centre Hospitalier Régional Universitaire, Caen, France; Pfizer Inc., Paris; and the Hôpital de la Salpètrière, Paris. Address reprint requests to Dr. Lépine, Hôpital Fernand Widal, 200 rue du Faubourg Saint-Denis, 75475 Paris Cedex 10, France. Funding for this study was provided by Pfizer, Inc.

Figure 1. Study Protocol and Progression of Remitted Patients With Highly Recurrent Major Depressive Disorder Randomly Assigned to Double-Blind Prophylactic Treatment With Sertraline (50 or 100 mg/day) or Placebo

Figure 2. Time Until Recurrence in Remitted Patients With Highly Recurrent Major Depressive Disorder Randomly Assigned to Double-Blind Prophylactic Treatment With Sertraline (50 or 100 mg/day) or Placebo

1. Kessler RC, McGonagle KA, Zhao S, Nelson CB, Hughes M, Eshleman S, Wittchen H-U, Kendler KS: Lifetime and 12-month prevalence of DSM-III-R psychiatric disorders in the United States: results from the National Comorbidity Survey. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1994; 51:8–19Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

2. Robins LN, Regier DA (eds): Psychiatric Disorders in America: The Epidemiologic Catchment Area Study. New York, Free Press, 1991Google Scholar

3. Wells KB, Stewart A, Hays RD, Burnam MA, Rogers W, Daniels M, Berry S, Greenfield S, Ware J: The functioning and well-being of depressed patients: results from the Medical Outcomes Study. JAMA 1989; 262:914–919Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

4. Hays RD, Wells KB, Sherbourne CD, Rogers W, Spritzer K: Functioning and well-being outcomes of patients with depression compared with chronic general medical illnesses. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1995:52:11–19Google Scholar

5. Murray CJ, Lopez AD: Global mortality, disability, and the contribution of risk factors: Global Burden of Disease Study. Lancet 1997; 349:1436–1442Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

6. Solomon DA, Keller MB, Leon AC, Mueller TI, Lavori PW, Shea MT, Coryell W, Warshaw M, Turvey C, Maser JD, Endicott J: Multiple recurrences of major depressive disorder. Am J Psychiatry 2000; 157:229–233Link, Google Scholar

7. Kupfer DJ: Long-term treatment of depression. J Clin Psychiatry 1991; 52:28–34Medline, Google Scholar

8. Anderson IM, Nutt DJ, Deakin JFW: Evidence-based guidelines for treating depressive disorders with antidepressants: a revision of the 1993 British Association for Psychopharmacology guidelines. J Psychopharmacol 2000; 14:3–20Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

9. Coppen A, Mendlewicz J, Kielholz P: Pharmacotherapy of Depressive Disorders: A Consensus Statement. Geneva, World Health Organization, 1986Google Scholar

10. World Health Organization Mental Health Collaborating Centers: Pharmacotherapy of depressive disorders: a consensus statement. J Affect Disord 1989; 17:197–198Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

11. Frank E, Kupfer DJ, Perel JM, Cornes C, Jarrett DB, Mallinger AG, Thase ME, McEachran AB, Grochocinski VJ: Three-year outcomes for maintenance therapies in recurrent depression. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1990; 47:1093–1099Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

12. Kocsis JH, Friedman RA, Markowitz JC, Leon AC, Miller NL, Gniwesch L, Parides M: Maintenance therapy for chronic depression: a controlled clinical trial of desipramine. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1996; 53:769–776Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

13. Stewart JW, Tricamo E, McGrath PJ, Quitkin FM: Prophylactic efficacy of phenelzine and imipramine in chronic atypical depression: likelihood of recurrence on discontinuation after 6 months’ remission. Am J Psychiatry 1997; 154:31–36Link, Google Scholar

14. Keller MB, Kocsis JH, Thase ME, Gelenberg AJ, Rush AJ, Koran L, Schatzberg A, Russell J, Hirschfeld R, Klein D, McCullough JP, Fawcett JA, Kornstein S, LaVange L, Harrison W (Sertraline Chronic Depression Study Group): Maintenance phase efficacy of sertraline for chronic depression: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA 1998; 280:1665–1672Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

15. Doogan DP, Caillard V: Sertraline in the prevention of depression. Br J Psychiatry 1992; 160:217–222Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

16. Montgomery SA, Dufour H, Brion S, Gailledreau J, LaQueille X, Ferrey G, Moron P, Parant-Lucena N, Singer L, Danion JM, Beuzen JN, Pierredon MA: The prophylactic efficacy of fluoxetine in unipolar depression. Br J Psychiatry Suppl 1988; 3:69–76Medline, Google Scholar

17. Montgomery SA, Dunbar G: Paroxetine is better than placebo in relapse prevention and the prophylaxis of recurrent depression. Int Clin Psychopharmacol 1993; 8:189–195Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

18. Hochstrasser B, Isaksen PM, Koponen H, Lauritzen L, Mahnert FA, Rouillon F, Wade AG, Andersen M, Pedersen SF, Swart JC, Nil R: Prophylactic effect of citalopram in unipolar recurrent depression. Br J Psychiatry 2001; 178:304–310Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

19. Greenhouse JB, Stangl D, Kupfer DJ, Prien RF: Methodologic issues in maintenance therapy clinical trials. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1991; 48:313–318Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

20. Frank E, Prien F, Jarrett RB, Keller MB, Kupfer DJ, Lavori PW, Rush AJ, Weissman MM: Conceptualization and rationale for consensus definitions of terms in major depressive disorder: remission, recovery, relapse, and recurrence. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1991; 48:851–855Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

21. Montgomery SA, Åsberg M: A new depression scale designed to be sensitive to change. Br J Psychiatry 1979; 134:382–389Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

22. Guy W (ed): ECDEU Assessment Manual for Psychopharmacology: Publication ADM 76–338. Washington, DC, US Department of Health, Education, and Welfare, 1976, pp 218–222Google Scholar