The Hamilton Depression Rating Scale: Has the Gold Standard Become a Lead Weight?

Abstract

OBJECTIVE: The Hamilton Depression Rating Scale has been the gold standard for the assessment of depression for more than 40 years. Criticism of the instrument has been increasing. The authors review studies published since the last major review of this instrument in 1979 that explicitly examine the psychometric properties of the Hamilton depression scale. The authors’ goal is to determine whether continued use of the Hamilton depression scale as a measure of treatment outcome is justified. METHOD: MEDLINE was searched for studies published since 1979 that examine psychometric properties of the Hamilton depression scale. Seventy studies were identified and selected, and then grouped into three categories on the basis of the major psychometric properties examined—reliability, item-response characteristics, and validity. RESULTS: The Hamilton depression scale’s internal reliability is adequate, but many scale items are poor contributors to the measurement of depression severity; others have poor interrater and retest reliability. For many items, the format for response options is not optimal. Content validity is poor; convergent validity and discriminant validity are adequate. The factor structure of the Hamilton depression scale is multidimensional but with poor replication across samples. CONCLUSIONS: Evidence suggests that the Hamilton depression scale is psychometrically and conceptually flawed. The breadth and severity of the problems militate against efforts to revise the current instrument. After more than 40 years, it is time to embrace a new gold standard for assessment of depression.

The Hamilton Depression Rating Scale (1) was developed in the late 1950s to assess the effectiveness of the first generation of antidepressants and was originally published in 1960. Although Hamilton (1) recognized that the scale had “room for improvement” (p. 56) and that further revision was necessary, the scale quickly became the standard measure of depression severity for clinical trials of antidepressants (2, 3). The Hamilton depression scale has retained this function and is now the most commonly used measure of depression (3). Our objective in this article is to provide a review of the Hamilton depression scale literature published since the last major evaluation of its psychometric properties, more than 20 years ago (4). More recent reviews have appeared (3, 5–7), but they have not systematically examined the literature with regard to a broad range of measurement issues. Significant developments in psychometric theory and practice have been made since the 1950s and need to be applied to instruments currently in use. We evaluate the Hamilton depression scale in light of these current standards and conclude by presenting arguments for and against retaining, revising, or rejecting the Hamilton depression scale as the gold standard for assessment of depression.

Method

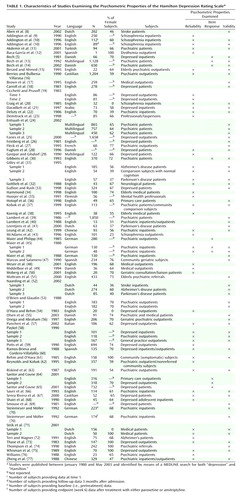

Studies for the review were identified by means of MEDLINE searches for both “depression” and “Hamilton.” All studies published during the period since the last major review (January 1980 to May 2003) were considered. Studies selected for review had to be explicitly designed to evaluate empirically the psychometric properties of the instrument or to review conceptual issues related to the instrument’s development, continued use, and/or shortcomings. At least 20 published versions of the Hamilton depression scale exist, including both longer and shortened versions. This review was limited to studies that examined the original 17-item version, as the majority of the studies that evaluated the scale’s psychometrics used the 17-item version. Only a small number of studies evaluated other versions, and most of these versions contain the original 17 items. Seventy articles met the selection criteria and were categorized into three groups on the basis of the major psychometric property examined—reliability, item response, and validity. Table 1 lists the articles included in the review.

Results

Reliability

Clinician-rated instruments should demonstrate three types of reliability: 1) internal reliability, 2) retest reliability, and 3) interrater reliability. Cronbach’s alpha statistic (78) is used to evaluate internal reliability, and estimates ≥0.70 reflect adequate reliability (79, 80). The internal reliability of individual items is calculated by using corrected item-to-total correlation with Pearson’s r; items should have a correlation greater than 0.20 (79, 80). Retest reliability assesses the extent to which multiple administrations of the scale generate the same results. When scores on an instrument are expected to change in response to effective treatment, it is necessary to demonstrate that these scores remain the same in the absence of treatment. Interrater reliability assesses the extent to which multiple raters generate the same result. Although Pearson’s r is often used to compute these estimates, the preferred method is the intraclass r (81), which allows for adjustment for agreement by chance. Estimates of retest and interrater reliability should be at a minimum of 0.70 (Pearson’s r) and 0.60 (intraclass r) (82). For retest reliability of scale items, Pearson’s r >0.70 is considered acceptable (83).

Internal Reliability

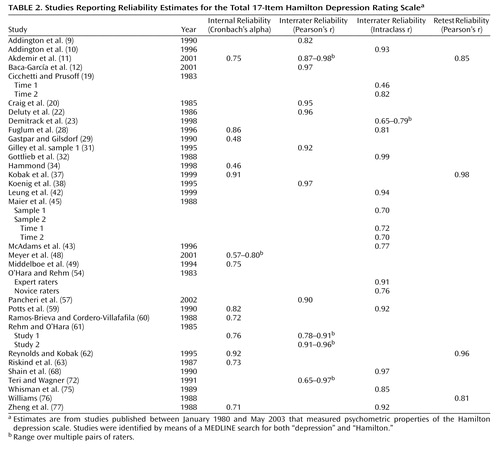

Table 2 summarizes the results from studies examining internal reliability of the total Hamilton depression scale. Estimates ranged from 0.46 to 0.97, and 10 studies reported estimates ≥0.70. Table 3 summarizes the studies that examined internal reliability at the item level. The majority of Hamilton depression scale items show adequate reliability. Six items met the reliability criteria in every sample (guilt, middle insomnia, psychic anxiety, somatic anxiety, gastrointestinal, general somatic), and an additional five items met the criteria in all but one sample (depressed mood, suicide, early insomnia, late insomnia, work and interests, hypochondriasis). Loss of insight was the item with the most variable findings, suggesting a potential problem with this item.

Interrater Reliability

Total Hamilton depression scale interrater reliabilities are displayed in Table 2. Pearson’s r ranged from 0.82 to 0.98, and the intraclass r ranged from 0.46 to 0.99. Some investigators provided evidence that the skill level or expertise of the interviewer and the provision of structured queries and scoring guidelines affect reliability (19, 23, 35, 54). Across studies, the best estimate mean of interrater reliability for studies reporting higher levels of interviewer skill and use of expert raters, structured queries, and scoring guidelines did not statistically differ from that for other studies (z=0.81, n.s.).

At the individual item level, interrater reliability is poor for many items. Cicchetti and Prusoff (19) assessed reliability before treatment initiation and 16 weeks later at trial end. Only early insomnia was adequately reliable before treatment, and only depressed mood was adequately reliable after treatment. Thirteen items had coefficients <0.50 before treatment, and 11 items had coefficients <0.50 after treatment. Rehm and O’Hara (61) performed a similar analysis with data from two samples. Six items showed adequate reliability in the first sample (early insomnia, middle insomnia, late insomnia, somatic anxiety, gastrointestinal, loss of libido), as did 10 in the second sample (depressed mood, guilt, suicide, early insomnia, middle insomnia, late insomnia, work/interests, psychic anxiety, somatic anxiety, gastrointestinal). Loss of insight showed the lowest interrater agreement in both samples. Craig et al. (20) found that only one item, work/interests, had adequate interrater reliability. Moberg et al. (50) reported that nine items demonstrated adequate reliability when the standard Hamilton depression scale was administered (depressed mood, guilt, suicide, early insomnia, late insomnia, agitation, psychic anxiety, hypochondriasis, loss of insight), but all items showed adequate reliability when the scale was administered with interview guidelines. Potts et al. (59) demonstrated that a single omnibus coefficient can mask specific problems. Using a structured interview version of the Hamilton depression scale, they found an overall intraclass coefficient of 0.92; however, two trained psychiatrists differed at least 20% of the time in their ratings of psychic anxiety, psychomotor agitation, and psychomotor retardation, and they differed by at least two points 15% of the time in their ratings of loss of libido. The ratings of trained raters disagreed with the psychiatrists’ ratings on psychomotor agitation (50% of the time), hypochondriasis (60%), loss of libido (90%), and loss of energy (100%).

Retest Reliability

Retest reliability for the Hamilton depression scale ranged from 0.81 to 0.98 (Table 2). Retest reliability at the item level (Table 3) ranged from 0.00 to 0.85. Williams (76) argued in favor of using structured interview guides to boost item and total scale reliability and developed the Structured Interview Guide for the Hamilton Depression Rating Scale. This effort increased the mean retest reliability across individual items to 0.54, although only four items met the criteria for adequate reliability (depressed mood, early insomnia, psychic anxiety, and loss of libido).

Item Characteristics

Content and scaling

Standard psychometric practice dictates that items within an instrument should measure a single symptom and contain response options linked to increasing or decreasing amounts of that symptom. Each item is assumed to contribute equally to the total score or be backed with evidence in support of differential weighting. These criteria are not consistently met by using the current scaling procedure or the options for rating symptoms. Although improperly scaled items can cause problems in quantitative measurement, evaluation of item scaling takes place first at a qualitative level. Some Hamilton depression scale items measure single symptoms along a meaningful continuum of severity; many do not. The item assessing depressed mood includes a combination of affective, behavioral, and cognitive features, such as gloomy attitude, pessimism about the future, subjective feeling of sadness, and tendency to weep. The general somatic symptoms item, which is also symptomatically heterogeneous, includes feelings of heaviness, diffuse backache, and loss of energy. Headache is coded only as part of somatic anxiety along with such symptoms as indigestion, palpitations, and respiratory difficulties. Genital symptoms for women entail loss of libido and menstrual disturbances. The problems inherent in the heterogeneity of these rating descriptors reduce the potential meaningfulness of these items, a problem exacerbated if the different components of an item actually measure multiple constructs and thus measure different effects.

Most items on the Hamilton depression scale at least are scaled so that increasing scores represent increasing severity. It is less clear whether the anchors used for different scores on certain items actually assess the same underlying construct/syndrome. This ambiguity is most obvious for severity ratings involving psychotic features. The feelings of guilt item, for example, is graded as follows: 0=absent, 1=self-reproach, 2=ideas of guilt or rumination over past errors or sinful deeds, 3=present illness is a punishment, and 4=hears accusatory or denunciatory voices and/or experiences threatening visual hallucinations. A patient with guilt-themed hallucinations may be more severely ill than a patient who has nonpsychotic guilty feelings, but is he/she feeling more guilt? The psychotic features may instead represent a qualitatively different construct/syndrome associated with more severe illness. Similarly, the hypochondriasis item progresses through bodily self-absorption (rated 1) and preoccupation with health (rated 2) before switching to querulous attitude (rated 3) and then again to hypochondriacal delusions (rated 4). These item-scoring anchors violate basic measurement principles, because nominal scaling and ordinal scaling are combined in a single item.

Although Hamilton (1) explained the rationale for the inclusion of both 3-point and 5-point items, the argument was not made on the grounds of differential weighting. Hamilton believed that certain items would be difficult to anchor dimensionally and therefore assigned them fewer response options. The end result is that certain items contribute more to the total score than others. Contrasting psychomotor retardation and psychomotor agitation, for example, reveals that a severe manifestation of the former contributes 4 points, whereas an equally severe manifestation of the latter contributes 2 points. Similarly, someone who weeps all the time can contribute 3 or 4 points on depressed mood, whereas someone who feels tired all the time can contribute only 2 points on the general somatic symptoms item.

Item Response Analysis

A psychiatric rating scale should measure a single psychopathological construct (i.e., an illness or syndrome) and be composed of items that adequately cover a range of symptoms that are consistently associated with the syndrome. Item response theory, a method used increasingly in the evaluation and construction of psychometric instruments, permits empirical evaluation of these premises. It is important to note that this method was not available when the original Hamilton depression scale was developed, although some researchers more recently used this method to evaluate this instrument. According to item response theory, a scale and its constituent items may have good reliability estimates but still fail to meet item response theory criteria. For example, if a depression scale were composed only of items measuring mild depression, the instrument would have great difficulty distinguishing between moderate and severe cases of depression, as both would be characterized by high scores on all items. This issue is particularly pressing in studies of clinical change; not only is a wide range of severity often represented in this research, but individual patients are expected to move along this continuum as they improve. Continued use of items insensitive to change underestimates the strength of actual treatment effects and makes it necessary to have larger samples to demonstrate that an effect is statistically significant. Falsely identifying patients as not having changed represents an additional source of “noise” and weakens the “signal” of a true treatment effect. A pragmatic implication of such lack of sensitivity is that new compounds shown to be promising in the laboratory may appear spuriously ineffective in clinical trials.

A related issue concerns the extent to which a severity score actually measures a single unidimensional syndrome. To summarize a syndrome with a single score requires a precise understanding of what that score represents. The implicit assumption is that the severity score represents a single dimension (84); if depression is heterogeneous, interpretation of a single summed score is unclear. If, for example, items assessing psychological and physical symptoms were only loosely related, a single score would not distinguish between two potentially different groups of depressed patients—one group whose symptoms were primarily psychological and another group with primarily vegetative symptoms. Any effects of an intervention targeting only one of these aspects would be harder to detect.

Gibbons et al. (85) presented a strategy for identifying a unidimensional set of items from a psychiatric rating scale and evaluating the extent to which these items adequately measure the full range of depression severity. Subsequently, a subset of Hamilton depression scale items that would measure a single dimension of depression across a wide range of severity was developed (30). This subset included depressed mood, which was sensitive at low levels; work/interests, psychic anxiety, and loss of libido, which were sensitive at mild levels; somatic anxiety, psychomotor agitation, and guilt, which were sensitive at moderate levels; and suicide, which was sensitive at severe levels. These items were proposed as a psychometrically stronger form of the full Hamilton depression scale.

Santor and Coyne (64, 65) used item response theory to examine the functioning of the full Hamilton depression scale and its individual items. In one of these studies (65) they examined individual Hamilton depression scale item performance in a combined sample of primary care patients and depressed patients from the National Institute of Mental Health Treatment of Depression Collaborative Research Program. One expects different item ratings at different levels of depression severity, with zeroes more common at mild levels of overall depression and higher item scores more common with more severe overall depression. Moreover, whereas most items on the Hamilton depression scale are, overall, sensitive to depression severity, 12 items had at least one problematic response option (the five items that had no such problems were depressed mood, guilt, suicide, work/interests, and psychic anxiety) (64). For example, the likelihood of receiving a rating of 1 on the insomnia items was essentially the same regardless of the overall severity of depression, but the likelihood of receiving a rating of 4 on somatic anxiety was very low even when overall depression was severe. These findings confirm that the rating scheme is not ideal for many items on the Hamilton depression scale, with the unfortunate effect of decreasing the capacity of the Hamilton depression scale to detect change (6, 7).

Rasch Analysis

Additional efforts to analyze the performance of individual Hamilton depression scale items and to identify an underlying single dimension of depression severity have benefited from a technique known as Rasch analysis, a method similar to item response theory. Rasch analysis proposes an ideal underlying dimension based on mathematical and theoretical reasoning about the construct that is being measured and then assesses the extent to which actual data correspond to this ideal. This approach was first applied to the Hamilton depression scale by Bech et al. (86), who confirmed that six items previously shown to have properties associated with unidimensionality (87) could be combined to create a shorter scale that met the formal Rasch criteria. This six-item scale was thus proposed as a better measure than the full Hamilton depression scale for assessing depression severity along a single dimension; the six-item scale is composed of items for depressed mood, guilt, work/interests, psychomotor retardation, anxiety psychic, and general somatic symptoms (87). The unidimensionality of this six-item subscale has since been confirmed in two studies that used Rasch methods (13, 14). Maier and Philipp (44) used Rasch analysis to confirm unidimensionality for a subset of Hamilton depression scale items. The resulting scale was similar to that obtained by Bech et al. (86). In another study that used Rasch analysis (46), six items were found to be problematic: suicide, psychomotor agitation, anxiety somatic, general somatic symptoms, hypochondriasis, and loss of insight.

Validity

Validity of psychiatric rating scales such as the Hamilton depression scale comprises 1) content, 2) convergent, 3) discriminant, 4) factorial, and 5) predictive validity. Content validity is assessed by examining scale items to determine correspondence with known features of a syndrome. Convergent validity is adequate when a scale shows Pearson’s r values of at least 0.50 in correlations with other measures of the same syndrome. Discriminant validity is established by showing that groups differing in their diagnostic status can be separated by using the scale. Predictive validity for symptom severity measures such as the Hamilton depression scale is determined by a statistically significant (p<0.05) capacity to predict change with treatment. Factorial validity is established by using factor analysis or related techniques (e.g., principal-component analysis) to demonstrate that a meaningful structure can be found in multiple samples. An a priori criterion of 0.40 has been used to identify which items are part of which factors (88).

Content validity

Because of its wide use and long clinical tradition, the Hamilton depression scale seems to both define as well as measure depression. One could criticize DSM-IV for not adequately capturing Hamilton depression scale depression as much as one could criticize the Hamilton depression scale for not providing full coverage of DSM-IV depression. Nonetheless, the operational criteria provided in DSM-IV are used as the official nosology for much of psychiatry worldwide. The criteria for major depression have been revised three times in response to developments in field trial research and clinical consensus based on expert opinion, most recently in 1994. Researchers have developed a number of longer versions of the Hamilton depression scale that include additional symptoms such as the reverse vegetative features of atypical depression. However, the core items of the Hamilton depression scale have remained unchanged for more than 40 years. It is reasonable to ask whether this instrument captures depression as it is currently conceptualized. Several symptoms contained within the Hamilton depression scale are not official DSM diagnostic criteria, although they are recognized as features associated with depression (e.g., psychic anxiety). For other symptoms included in the Hamilton depression scale (e.g., loss of insight, hypochondriasis), the link with depression is more tenuous. More critically, important features of DSM-IV depression are often buried within more complex items and sometimes are not captured at all. The work/interests item includes anhedonic features along with listlessness, indecisiveness, social avoidance, and lowered productivity. It is impossible to determine the extent to which anhedonia per se influences severity. Guilt is captured in both Hamilton depression scale depression and DSM-IV depression, but the Hamilton depression scale contains no explicit assessment of feelings of worthlessness. Decision-making difficulties are buried within the work/interests item of the Hamilton depression scale, but concentration difficulties are not included. The reverse vegetative symptoms—weight gain, hyperphagia, and hypersomnia—were provided by Hamilton (1) as additional items but are not scored on the original Hamilton depression scale.

Convergent validity

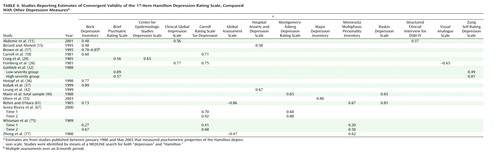

A wide range of instruments has been used to examine the convergent validity of the Hamilton depression scale (Table 4). Most of the correlation coefficients met the preestablished criterion, and the Hamilton depression scale showed adequate convergent validity in correlations with all but two scales, including the major depression section of the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV. The latter finding provides evidence of noncorrespondence between the Hamilton depression scale and DSM-IV.

Discriminant validity

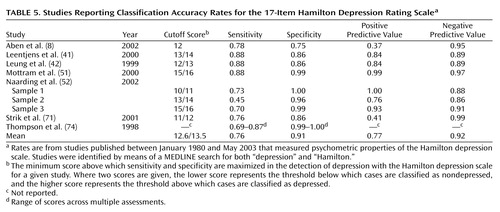

Two approaches have been used to evaluate the discriminant validity of the Hamilton depression scale. In the first approach, several studies used the receiver operating curve as a statistical means of determining the cutoff scores for detecting depression and then provided corresponding rates of sensitivity, specificity, positive predictive power, and negative predictive power for the Hamilton depression scale in distinguishing depressed and nondepressed subjects. In other studies, researchers have examined the capacity of the Hamilton depression scale to distinguish different groups of clinical patients (e.g., patients with endogenous versus those with nonendogenous depression, patients with anxiety versus those with depression) using statistical techniques to detect mean group differences. Classification rates resulting from receiver operating curve analysis have not been widely reported in the Hamilton depression scale literature. Our search only identified seven studies (Table 5), and some of these investigations sought to detect depression in samples of patients with medical conditions other than psychiatric disorders (Table 1). Sensitivity, specificity, and negative predictive power were generally consistent and large, but positive predictive power was more variable, and two studies reported very low positive predictive power.

The second type of discriminant validity study attempts to distinguish different clinical groups. In a comparison of healthy, depressed, and bipolar depressed individuals, Rehm and O’Hara (61) found that the total Hamilton depression scale score clearly differentiated these three categories, with the depressed patients scoring higher than the healthy participants and with the bipolar depressed patients scoring higher than both of the other groups. At the item level, four items—psychomotor agitation, gastrointestinal symptoms, loss of insight, and weight loss—failed to differentiate depressed from healthy subjects. Only psychic anxiety and hypochondriasis significantly differentiated the subjects with unipolar and bipolar depression. Kobak et al. (37) showed significant total scale score differences between individuals with major depression, individuals with minor depression, and healthy comparison subjects. Zheng et al. (77) reported that the Hamilton depression scale was able to discriminate psychiatric patients classified as mildly, moderately, and severely dysfunctional on the basis of Global Severity Scale scores. Thase et al. (73) found that the Hamilton depression scale could distinguish patients with endogenous depression from patients with nonendogenous depression, with patients in the former category having higher scores. Gottlieb et al. (32) reported no significant differences between the Hamilton depression scale scores of patients classified as having low-severity versus high-severity Alzheimer’s disease. Several researchers have investigated the capacity of the Hamilton depression scale to differentiate between patients with anxiety and those with depression. Prusoff and Klerman (89) suggested the Hamilton depression scale could indeed separate these constructs, and Maier et al. (45) demonstrated that the Hamilton depression scale had a higher correlation with an external measure of depression than with an external measure of anxiety, but the saturation of the Hamilton depression scale with anxiety-related concepts was nonetheless considerable.

Predictive validity

Edwards et al. (90) performed a meta-analysis of 19 studies with a total of 1,150 patients that compared the predictive validity of the Hamilton depression scale and the Beck Depression Inventory. Treatments included pharmacotherapy, behavior therapy, cognitive restructuring, dynamic psychotherapy, and various combinations. The Hamilton depression scale was found to be more sensitive to change, compared to the Beck Depression Inventory. Lambert et al. (39) performed a meta-analysis that included 36 studies and a total of 1,850 patients and that compared the Hamilton depression scale to the Beck Depression Inventory and the Zung Self-Rating Depression Scale. They reported that the Hamilton depression scale was more sensitive to change than were the two self-report measures. Sayer et al. (66) also demonstrated that the Hamilton depression scale outperformed the Beck Depression Inventory in detecting change. Lambert et al. (40) reported that the Beck Depression Inventory is more likely to show treatment effects at 12 weeks than the Zung Self-Rating Depression Scale or the Hamilton depression scale; the Zung Self-Rating Depression Scale and the Hamilton depression scale were more likely to detect changes after 3 weeks.

One disadvantage of a multidimensional instrument such as the Hamilton depression scale in detecting change is that specific treatments may affect only a single dimension. If the total score includes somatic symptoms that actually reflect treatment side effects, estimates of treatment response will be spuriously low (44). In two studies and one meta-analysis researchers addressed this issue using the various unidimensional core depression item sets described earlier in the section on item characteristics (91, 92). The six-item subscale developed by Bech et al. (87) was found to be at least as responsive as the full Hamilton depression scale. A meta-analysis of eight fluoxetine studies with 1,658 patients showed that the different unidimensional subscales (44, 87) were more sensitive to change than was the full Hamilton depression scale score. These results were replicated in a second meta-analysis of four tricyclic antidepressant studies (25).

Factorial validity

A total of 15 studies with 17 samples reported a factor analysis of the Hamilton depression scale (Table 6). In most of the studies, researchers used the eigenvalue ≥1 rule to determine the number of factors, extracted those factors from the data using principal-component analysis, and then determined the optimal configuration of items on factors using varimax rotation. The number of factors identified ranged from two to eight. Insomnia items appeared consistently on the same factor in 13 data sets, suggesting a sleep disturbance factor. There was some support for the presence of a general depression factor, as depressed mood, guilt, and suicide appeared together on the same factor in six data sets, and the combination of depressed mood, suicide, and psychic anxiety appeared on the same factor in seven data sets. Support was also found for an anxiety/agitation factor, with the agitation, psychic anxiety, and somatic anxiety items appearing together in six samples. Clearly, the Hamilton depression scale is not unidimensional, as separate sets of items do seem to reliably represent general depression and insomnia factors; however, the exact structure of the Hamilton depression scale’s multidimensionality remains unclear.

Conclusions

The Hamilton depression scale has been the standard for the assessment of depression for more than 40 years. Researchers and policy makers charged with the task of providing standards to evaluate treatment outcomes in depression are faced with three possible solutions: retain, revise, or reject. The latter solution argues for the development of a new instrument or the replacement of the Hamilton depression scale with existing, psychometrically superior instruments.

Many of the psychometric properties of the Hamilton depression scale are adequate and consistently meet established criteria. The internal, interrater, and retest reliability estimates for the overall Hamilton depression scale are mostly good, as are the internal reliability estimates at the item level. Similarly, established criteria are met for convergent, discriminant, and predictive validity, although the latter does suffer somewhat due to multidimensionality. At the item level, interrater and retest coefficients are weak for many items, and the internal reliability coefficients indicate that some items are problematic. The lack of individual item reliability is not necessarily a fatal psychometric flaw; what is critical is that the items as a whole provide adequate reliability.

Evaluation of item response shows that many of the individual items are poorly designed and sum to generate a total score whose meaning is multidimensional and unclear. The problem of multidimensionality was highlighted in the evaluation of factorial validity, which showed a failure to replicate a single unifying structure across studies. Although the unstable factor structure of the Hamilton depression scale may be partly attributable to the diagnostic diversity of population samples, well-designed scales assessing clearly defined constructs produce factor structures that are invariant across different populations (88). Finally, the Hamilton depression scale is measuring a conception of depression that is now several decades old and that is, at best, only partly related to the operationalization of depression in DSM-IV.

These findings indicate that continued use of the Hamilton depression scale requires, at the very least, a complete overhaul of its constituent items. Accumulated empirical evidence offers some hope that substantial revision can redress a number of psychometric problems, thereby providing an improved measure. Shortened versions of the Hamilton depression scale converge on a common set of core features and in general have proven more effective in detecting change. The truncated item sets for these instruments, however, are limited in that they do not permit capture of the full depressive syndrome. Other studies based on item response theory methods have indicated that modifications of the rating scheme are readily implemented and can enhance the unidimensionality of these core symptoms in a manner that allows uniform assessment of change. Identifying a core set of symptoms with proven psychometric qualities, along with making rating scheme changes that would allow consistent assessment of the severity of depression, could provide a foundation for a reconstructed scale. One advantage of such a revision is that it would maintain continuity with the long-standing use of the original Hamilton depression scale. This sort of transition is probably more palatable and therefore more readily acceptable to regulatory commissions.

The Depression Rating Scale Standardization Team revised the Hamilton depression scale (i.e., the GRID-HAMD [93, 94]) by employing several of the methodological advances we have been advocating in this article. They used item response theory methods to inform, in part, the revision process; developed clear structured interview prompts and scoring guidelines; and to some extent standardized the scoring system. We nonetheless believe that by making an effort to retain the original 17 items, the Depression Rating Scale Standardization Team failed to address many of the flaws of the original instrument. Most of the items still measure multiple constructs, items that have consistently been shown to be ineffective have been retained, and the scoring system still includes differential weighting of items. Moreover, the GRID-HAMD content is virtually unchanged from the original. All the items that appeared on the Hamilton depression scale in 1960 are included in the GRID-HAMD. Thus, this revision has neither removed items based on outdated concepts nor added items that incorporate contemporary definitions of depression.

Rejection of the Hamilton depression scale and replacement with an alternative existing measure or the implementation of a new instrument has scientifically compelling advantages over revision. The Inventory of Depressive Symptomatology (95) and the Montgomery-Åsberg Depression Rating Scale (96), designed to address the limitations of the Hamilton depression scale, represent two potential replacement alternatives. Although these instruments measure contemporary definitions of depression (33), neither item response theory methods nor other contemporary measurement techniques were employed in their development. As indicated earlier, such techniques, especially item response theory, maximize the capacity of an instrument to detect change. On the other hand, the development and implementation of a new instrument that is based on current knowledge of depression and that takes advantage of psychometric and statistical advances might offer the best solution. The decision to replace the Hamilton depression scale with either an existing instrument or a newly developed instrument would ultimately rest on consensus that such an instrument could capture more adequately the full spectrum of the depression construct and on empirical evidence of the new instrument’s superiority in detecting treatment effects.

In conclusion, we have been struck with the marked contrast between the effort and scientific sophistication involved in designing new antidepressants and the continued reliance on antiquated concepts and methods for assessing change in the severity of the depression that these very medications are intended to affect. Effort in both areas is critical to the accessibility of new medications for patients with depression. Many scales and instruments used in psychiatry today are based on—or at least include—current DSM symptoms, and the measurement of depression should follow this trend. It is time to retire the Hamilton depression scale. The field needs to move forward and embrace a new gold standard that incorporates modern psychometric methods and contemporary definitions of depression.

|

|

|

|

|

|

Received Dec. 7, 2003; revision received Feb. 26, 2004; accepted March 22, 2004. From the Centre for Addiction and Mental Health, University of Toronto; and the Department of Psychology, University of British Columbia, Vancouver, B.C. Address reprint requests to Dr. Bagby, Centre for Addiction and Mental Health, 250 College St., Toronto, Ont., Canada M5T 1R8; [email protected] (e-mail). Supported in part by Eli Lilly and Co. and by a Senior Research Fellowship from the Ontario Mental Health Foundation to Dr. Bagby. Mr. Ryder was supported by a postdoctoral fellowship from the Michael Smith Foundation for Health Research, Vancouver, B.C., Canada. The authors thank Arun Ravindrun and Sid Kennedy for their comments and Natasha Owen for assistance with the manuscript.

1. Hamilton M: A rating scale for depression. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 1960; 23:56–62Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

2. Demyttenaere K, De Fruyt J: Getting what you ask for: on the selectivity of depression rating scales. Psychother Psychosom 2003; 72:61–70Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

3. Williams JB: Standardizing the Hamilton Depression Rating Scale: past, present, and future. Eur Arch Psychiatry Clin Neurosci 2001; 251(suppl 2):II6-II12Google Scholar

4. Hedlund JL, Vieweg BW: The Hamilton Rating Scale for Depression: a comprehensive review. J Operational Psychiatry 1979; 10:149–165Google Scholar

5. Bech P: Rating scales for affective disorders: their validity and consistency. Acta Psychiatr Scand Suppl 1981; 295:1–101Medline, Google Scholar

6. Bech P: Psychometric development of the Hamilton scales: the spectrum of depression, dysthymia and anxiety, in The Hamilton Scales. Edited by Bech P, Coppen A. Berlin, Springer-Verlag, 1990, pp 72–79Google Scholar

7. Maier W: The Hamilton Depression Scale and its alternatives: a comparison of their reliability and validity, ibid, pp 64–71Google Scholar

8. Aben I, Verhey F, Lousberg R, Lodder J, Honig A: Validity of the Beck Depression Inventory, Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale, SCL-90, and Hamilton Depression Rating Scale as screening instruments for depression in stroke patients. Psychosomatics 2002; 43:386–393Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

9. Addington D, Addington J, Schissel B: A depression rating scale for schizophrenics. Schizophr Res 1990; 3:247–251Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

10. Addington D, Addington J, Atkinson M: A psychometric comparison of the Calgary Depression Scale for Schizophrenia and the Hamilton Depression Rating Scale. Schizophr Res 1996; 19:205–212Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

11. Akdemir A, Turkcapar MH, Orsel SD, Demirergi N, Dag I, Ozbay MH: Reliability and validity of the Turkish version of the Hamilton Depression Rating Scale. Compr Psychiatry 2001; 42:161–165Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

12. Baca-Garcia E, Blanco C, Saiz-Ruiz J, Rico F, Diaz-Sastre C, Cicchetti DV: Assessment of reliability in the clinical evaluation of depressive symptoms among multiple investigators in a multicenter clinical trial. Psychiatry Res 2001; 102:163–173Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

13. Bech P, Allerup P, Maier W, Albus M, Lavori P, Ayuso JL: The Hamilton scales and the Hopkins Symptom Checklist (SCL-90): a cross-national validity study in patients with panic disorders. Br J Psychiatry 1992; 160:206–211Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

14. Bech P, Tanghoj P, Andersen HF, Overo K: Citalopram dose-response revisited using an alternative psychometric approach to evaluate clinical effects of four fixed citalopram doses compared to placebo in patients with major depression. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2002; 163:20–25Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

15. Berard RMF, Ahmed N: Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS) as a screening instrument in a depressed adolescent and young adult population. Int J Adolesc Med Health 1995; 8:157–166Google Scholar

16. Berrios GE, Bulbena-Villarasa A: The Hamilton Depression Scale and the numerical description of the symptoms of depression, in The Hamilton Scales. Edited by Bech P, Coppen A. Berlin, Springer-Verlag, 1990, pp 80–92Google Scholar

17. Brown C, Schulberg HC, Madonia MJ: Assessing depression in primary care practice with the Beck Depression Inventory and the Hamilton Rating Scale for Depression. Psychol Assess 1995; 7:59–65Crossref, Google Scholar

18. Carroll BJ, Feinberg M, Smouse PE, Rawson SG, Greden JF: The Carroll Rating Scale for Depression, I: development, reliability and validation. Br J Psychiatry 1981; 138:194–200Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

19. Cicchetti DV, Prusoff BA: Reliability of depression and associated clinical symptoms. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1983; 40:987–990Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

20. Craig TJ, Richardson MA, Pass R, Bregman Z: Measurement of mood and affect in schizophrenic inpatients. Am J Psychiatry 1985; 142:1272–1277Link, Google Scholar

21. Daradkeh T, Abou-Saleh M, Karim L: The factorial structure of the 17-item Hamilton Depression Rating Scale. Arab J Psychiatry 1997; 8:6–12Google Scholar

22. Deluty BM, Deluty RH, Carver CS: Concordance between clinicians’ and patients’ ratings of anxiety and depression as mediated by private self-consciousness. J Pers Assess 1986; 50:93–106Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

23. Demitrack MA, Faries D, Herrera JM, DeBrota D, Potter WZ: The problem of measurement error in multisite clinical trials. Psychopharmacol Bull 1998; 34:19–24Medline, Google Scholar

24. Entsuah R, Shaffer M, Zhang J: A critical examination of the sensitivity of unidimensional subscales derived from the Hamilton Depression Rating Scale to antidepressant drug effects. J Psychiatr Res 2002; 36:437–448Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

25. Faries D, Herrera J, Rayamajhi J, DeBrota D, Demitrack M, Potter WZ: The responsiveness of the Hamilton Depression Rating Scale. J Psychiatr Res 2000; 34:3–10Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

26. Feinberg M, Carroll BJ, Smouse PE, Rawson SG: The Carroll Rating Scale for Depression, III: comparison with other rating instruments. Br J Psychiatry 1981; 138:205–209Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

27. Fleck MP, Poirier-Littre MF, Guelfi JD, Bourdel MC, Loo H: Factorial structure of the 17-item Hamilton Depression Rating Scale. Acta Psychiatr Scand 1995; 92:168–172Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

28. Fuglum E, Rosenberg C, Damsbo N, Stage K, Lauritzen L, Bech P (Danish University Antidepressant Group): Screening and treating depressed patients: a comparison of two controlled citalopram trials across treatment settings: hospitalized patients vs patients treated by their family doctors. Acta Psychiatr Scand 1996; 94:18–25Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

29. Gastpar M, Gilsdorf U: The Hamilton Depression Rating Scale in a WHO collaborative program, in The Hamilton Scales. Edited by Bech P, Coppen A. Berlin, Springer-Verlag, 1990, pp 10–19Google Scholar

30. Gibbons RD, Clark DC, Kupfer DJ: Exactly what does the Hamilton Depression Rating Scale measure? J Psychiatr Res 1993; 27:259–273Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

31. Gilley DW, Wilson RS, Fleischman DA, Harrison DW, Goetz CG, Tanner CM: Impact of Alzheimer’s-type dementia and information source on the assessment of depression. Psychol Assess 1995; 7:42–48Crossref, Google Scholar

32. Gottlieb GL, Gur RE, Gur RC: Reliability of psychiatric scales in patients with dementia of the Alzheimer type. Am J Psychiatry 1988; 145:857–860Link, Google Scholar

33. Gullion CM, Rush AJ: Toward a generalizable model of symptoms in major depressive disorder. Biol Psychiatry 1998; 44:959–972Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

34. Hammond MF: Rating depression severity in the elderly physically ill patient: reliability and factor structure of the Hamilton and the Montgomery-Åsberg Depression Rating Scales. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry 1998; 13:257–261Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

35. Hooijer C, Zitman FG, Griez E, van Tilburg W, Willemse A, Dinkgreve MA: The Hamilton Depression Rating Scale (HDRS); changes in scores as a function of training and version used. J Affect Disord 1991; 22:21–29Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

36. Hotopf M, Sharp D, Lewis G: What’s in a name? a comparison of four psychiatric assessments. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol 1998; 33:27–31Medline, Google Scholar

37. Kobak KA, Greist JH, Jefferson JW, Mundt JC, Katzelnick DJ: Computerized assessment of depression and anxiety over the telephone using interactive voice response. MD Comput 1999; 16:64–68Medline, Google Scholar

38. Koenig HG, Pappas P, Holsinger T, Bachar JR: Assessing diagnostic approaches to depression in medically ill older adults: how reliably can mental health professionals make judgments about the cause of symptoms? J Am Geriatr Soc 1995; 43:472–478Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

39. Lambert MJ, Hatch DR, Kingston MD, Edwards BC: Zung, Beck, and Hamilton Rating Scales as measures of treatment outcome: a meta-analytic comparison. J Consult Clin Psychol 1986; 54:54–59Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

40. Lambert MJ, Masters KS, Astle D: An effect-size comparison of the Beck, Zung, and Hamilton rating scales for depression: a three-week and twelve-week analysis. Psychol Rep 1988; 63:467–470Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

41. Leentjens AF, Verhey FR, Lousberg R, Spitsbergen H, Wilmink FW: The validity of the Hamilton and Montgomery-Åsberg depression rating scales as screening and diagnostic tools for depression in Parkinson’s disease. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry 2000; 15:644–649Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

42. Leung CM, Wing YK, Kwong PK, Lo A, Shum K: Validation of the Chinese-Cantonese version of the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale and comparison with the Hamilton Rating Scale of Depression. Acta Psychiatr Scand 1999; 100:456–461Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

43. McAdams LA, Harris MJ, Bailey A, Fell R, Jeste DV: Validating specific psychopathology scales in older outpatients with schizophrenia. J Nerv Ment Dis 1996; 184:246–251Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

44. Maier W, Philipp M: Improving the assessment of severity of depressive states: a reduction of the Hamilton Depression Rating Scale. Pharmacopsychiatry 1985; 18:114–115Crossref, Google Scholar

45. Maier W, Philipp M, Heuser I, Schlegel S, Buller R, Wetzel H: Improving depression severity assessment, I: reliability, internal validity and sensitivity to change of three observer depression scales. J Psychiatr Res 1988; 22:3–12Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

46. Maier W, Heuser I, Philipp M, Frommberger U, Demuth W: Improving depression severity assessment, II: content, concurrent and external validity of three observer depression scales. J Psychiatr Res 1988; 22:13–19Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

47. Marcos T, Salamero M: Factor study of the Hamilton Rating Scale for Depression and the Bech Melancholia Scale. Acta Psychiatr Scand 1990; 82:178–181Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

48. Meyer JS, Li YS, Thornby J: Validating mini-mental status, cognitive capacity screening and Hamilton depression scales utilizing subjects with vascular headaches. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry 2001; 16:430–435Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

49. Middelboe T, Ovesen L, Mortensen EL, Bech P: Depressive symptoms in cancer patients undergoing chemotherapy: a psychometric analysis. Psychother Psychosom 1994; 61:171–177Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

50. Moberg PJ, Lazarus LW, Mesholam RI, Bilker W, Chuy IL, Neyman I, Markvart V: Comparison of the standard and structured interview guide for the Hamilton Depression Rating Scale in depressed geriatric inpatients. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry 2001; 9:35–40Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

51. Mottram P, Wilson K, Copeland J: Validation of the Hamilton Depression Rating Scale and Montgomery and Åsberg Rating Scales in terms of AGECAT depression cases. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry 2000; 15:1113–1119Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

52. Naarding P, Leentjens AF, van Kooten F, Verhey FR: Disease-specific properties of the Rating Scale for Depression in patients with stroke, Alzheimer’s dementia, and Parkinson’s disease. J Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci 2002; 14:329–334Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

53. O’Brien KP, Glaudin V: Factorial structure and factor reliability of the Hamilton Rating Scale for Depression. Acta Psychiatr Scand 1988; 78:113–120Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

54. O’Hara MW, Rehm LP: Hamilton Rating Scale for Depression: reliability and validity of judgments of novice raters. J Consult Clin Psychol 1983; 51:318–319Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

55. Olsen LR, Jensen DV, Noerholm V, Martiny K, Bech P: The internal and external validity of the Major Depression Inventory in measuring severity of depressive states. Psychol Med 2003; 33:351–356Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

56. Onega LL, Abraham IL: Factor structure of the Hamilton Rating Scale for Depression in a cohort of community-dwelling elderly. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry 1997; 12:760–764Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

57. Pancheri P, Picardi A, Pasquini M, Gaetano P, Biondi M: Psychopathological dimensions of depression: a factor study of the 17-item Hamilton depression rating scale in unipolar depressed outpatients. J Affect Disord 2002; 68:41–47Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

58. Paykel ES: Use of the Hamilton Depression Scale in General Practice, in The Hamilton Scales. Edited by Bech P, Coppen A. Berlin, Springer-Verlag, 1990, pp 40–47Google Scholar

59. Potts MK, Daniels M, Burnam MA, Wells KB: A structured interview version of the Hamilton Depression Rating Scale: evidence of reliability and versatility of administration. J Psychiatr Res 1990; 24:335–350Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

60. Ramos-Brieva JA, Cordero-Villafafila A: A new validation of the Hamilton Rating Scale for Depression. J Psychiatr Res 1988; 22:21–28Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

61. Rehm LP, O’Hara MW: Item characteristics of the Hamilton Rating Scale for Depression. J Psychiatr Res 1985; 19:31–41Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

62. Reynolds WM, Kobak KA: Reliability and validity of the Hamilton Depression Inventory: a paper-and-pencil version of the Hamilton Depression Rating Scale clinical interview. Psychol Assess 1995; 7:472–483Crossref, Google Scholar

63. Riskind JH, Beck AT, Brown G, Steer RA: Taking the measure of anxiety and depression: validity of the reconstructed Hamilton scales. J Nerv Ment Dis 1987; 175:474–479Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

64. Santor DA, Coyne JC: Evaluating the continuity of symptomatology between depressed and nondepressed individuals. J Abnorm Psychol 2001; 110:216–225Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

65. Santor DA, Coyne JC: Examining symptom expression as a function of symptom severity: item performance on the Hamilton Rating Scale for Depression. Psychol Assess 2001; 13:127–139Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

66. Sayer NA, Sackheim HA, Moeller JR, Prudic J, Devanand DP, Coleman EA, Kiersky JE: The relations between observer-rating and self-report of depressive symptomatology. Psychol Assess 1993; 5:350–360Crossref, Google Scholar

67. Senra Rivera C, Racano Perez C, Sanchez Cao E, Barba Sixto S: Use of three depression scales for evaluation of pretreatment severity and of improvement after treatment. Psychol Rep 2000; 87:389–394Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

68. Shain BN, Naylor M, Alessi N: Comparison of self-rated and clinician-rated measures of depression in adolescents. Am J Psychiatry 1990; 147:793–795Link, Google Scholar

69. Smouse PE, Feinberg M, Carroll BJ, Park MH, Rawson SG: The Carroll Rating Scale for Depression, II: factor analyses of the feature profiles. Br J Psychiatry 1981; 138:201–204Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

70. Steinmeyer EM, Möller HJ: Facet theoretic analysis of the Hamilton-D scale. J Affect Disord 1992; 25:53–61Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

71. Strik JJ, Honig A, Lousberg R, Denollet J: Sensitivity and specificity of observer and self-report questionnaires in major and minor depression following myocardial infarction. Psychosomatics 2001; 42:423–428Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

72. Teri L, Wagner AW: Assessment of depression in patients with Alzheimer’s disease: concordance among informants. Psychol Aging 1991; 6:280–285Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

73. Thase ME, Hersen M, Bellack AS, Himmelhoch JM, Kupfer DJ: Validation of a Hamilton subscale for endogenomorphic depression. J Affect Disord 1983; 5:267–278Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

74. Thompson WM, Harris B, Lazarus J, Richards C: A comparison of the performance of rating scales used in the diagnosis of postnatal depression. Acta Psychiatr Scand 1998; 98:224–227Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

75. Whisman MA, Strosahl K, Fruzzetti AE, Schmaling KB, Jacobson NS, Miller DM: A structured interview version of the Hamilton Rating Scale for Depression: reliability and validity. Psychol Assess 1989; 1:238–241Crossref, Google Scholar

76. Williams JB: A structured interview guide for the Hamilton Depression Rating Scale. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1988; 45:742–747Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

77. Zheng YP, Zhao JP, Phillips M, Liu JB, Cai MF, Sun SQ, Huang MF: Validity and reliability of the Chinese Hamilton Depression Rating Scale. Br J Psychiatry 1988; 152:660–664Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

78. Cronbach LJ: Coefficient alpha and the internal structure of tests. Psychometrika 1951; 16:297–334Crossref, Google Scholar

79. Briggs SR, Cheek JM: The role of factor analysis in the development and evaluation of personality scales. J Pers 1986; 54:106–148Crossref, Google Scholar

80. Nunnally JC, Bernstein IH: Psychometric Theory, 3rd ed. New York, McGraw-Hill, 1994Google Scholar

81. Fleiss JL, Shrout PE: The effects of measurement errors on some multivariate procedures. Am J Public Health 1977; 67:1188–1191Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

82. Landis JR, Koch GG: The measurement of observer agreement for categorical data. Biometrics 1977; 33:159–174Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

83. Anastasi A, Urbina S: Psychological Testing, 7th ed. New York, MacMillan, 1997Google Scholar

84. Bock RD, Gibbons RD, Murraki E: Full information item factor analysis. Applied Psychol Measurement 1988; 12:261–280Crossref, Google Scholar

85. Gibbons RD, Clark DC, VonAmmon CS, Davis JM: Application of modern psychometric theory in psychiatric research. J Psychiatr Res 1985; 19:43–55Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

86. Bech P, Allerup P, Gram LF, Reisby N, Rosenberg R, Jacobsen O, Nagy A: The Hamilton depression scale: evaluation of objectivity using logistic models. Acta Psychiatr Scand 1981; 63:290–299Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

87. Bech P, Gram LF, Dein E, Jacobsen O, Vitger J, Bolwig TG: Quantitative rating of depressive states. Acta Psychiatr Scand 1975; 51:161–170Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

88. Gorsuch RL: Factor Analysis. Hillside, NJ, Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, 1983Google Scholar

89. Prusoff B, Klerman GL: Differentiating depressed from anxious neurotic outpatients. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1974; 30:302–309Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

90. Edwards BC, Lambert MJ, Moran PW, McCully T, Smith KC, Ellingson AG: A meta-analytic comparison of the Beck Depression Inventory and the Hamilton Rating Scale for Depression as measures of treatment outcome. Br J Clin Psychol 1984; 23(part 2):93–99Google Scholar

91. O’Sullivan RL, Fava M, Agustin C, Baer L, Rosenbaum JF: Sensitivity of the six-item Hamilton Depression Rating Scale. Acta Psychiatr Scand 1997; 95:379–384Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

92. Hooper CL, Bakish D: An examination of the sensitivity of the six-item Hamilton Rating Scale for Depression in a sample of patients suffering from major depressive disorder. J Psychiatry Neurosci 2000; 25:178–184Medline, Google Scholar

93. Kalai A, Ginertini M, Kobak K, Engelhardt N, Williams JBW, Evans K, Bech P, Lipsitz J, Olin J, Pearson J, Rothman M: The GRID-HAMD: a reliability study in patients with major depression, in Abstracts of the 43rd Annual New Clinical Drug Evaluation Unit (NCDEU) Meeting. Bethesda, Md, NIMH, 2003, Poster I-19Google Scholar

94. Kalai A, Williams JB, Koback KA, Lipsitz J, Engelhardt N, Evans K, Olin J, Pearson J, Rothman M, Bech P: The new GRID HAM-D: pilot testing and international field trials. Int J Neuropsychopharmacol 2002; 5:S147-S148Google Scholar

95. Rush AJ, Giles DE, Schlesser MA, Fulton CL, Weissenburger J, Burns C: The Inventory for Depressive Symptomatology (IDS): preliminary findings. Psychiatry Res 1986; 18:65–87Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

96. Montgomery SA, Åsberg M: A new depression scale designed to be sensitive to change. Br J Psychiatry 1979; 134:382–389Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar