Saint Jerome in a Dark Chamber: Rembrandt’s Metaphoric Portrayal of the Depressed Mind

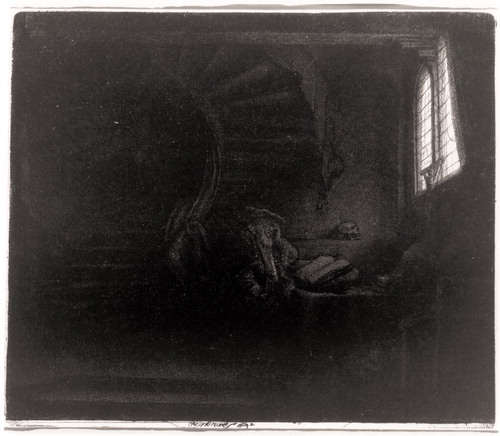

I first saw Rembrandt’s etching of Saint Jerome in a Dark Chamber (Figure 1) more than 20 years ago at an exhibition titled “Printmaking in the Age of Rembrandt” at the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston. At first glance, from a distance, this etching appeared to be a very dark, solid black print. I immediately headed toward it, since I am attracted to black in art, for reasons that I don’t fully understand. But I do know that, on close examination, black often leads to a sense of mystery, which I feel is the essence of all great art.

The etching is 15.0 × 17.6 cm, i.e., about 5.9 inches high and 6.9 inches wide. When first seen up close, it still appeared to be a solid black sheet, with the exception of the upper right corner, where bright light was shining in a small window. Upon continued examination, I could gradually see that this etching depicted a very dark chamber, within which there were some very dim figures that I could barely make out. After long and close examination, emerging out of the darkness of the chamber I found St. Jerome, seated at a table with a book in front of him, his hand supporting his head in a manner typical of melancholia. In the background there was a skull on a shelf. A crucifix hanging in the window was perhaps the most illuminated and clearest object in the etching. Upon further examination a circular staircase emerged, as did St. Jerome’s Cardinal’s hat hanging on a wall. Little else could be discerned.

Though I had never seen it before, this etching left me with an odd sense of familiarity. I couldn’t get it out of my mind, and I kept returning to it again and again. Then it struck me. This etching was essentially communicating to me in the same way that depressed patients did when, in their labored speech, they tried to describe what was going on in their minds. All was dark, and thoughts or objects were very dim. They often couldn’t describe what was there, and when they could, they couldn’t relate one mental representation to another. And most importantly, they would often say, “I can see the light out there in the world, but the light just doesn’t get into my brain. My mind remains dark—it is black.”

Suddenly, I realized that what Rembrandt depicted in this etching was not physically possible. With such a bright light in the window, this chamber could not possibly have remained so very dark. Clearly, Rembrandt knew this; then why did he do it? And I found myself wondering what might have been going on in Rembrandt’s life in the year, 1642, that he created this etching. That led me to do a bit of research, and I quickly discovered that 1642 was the year in which Rembrandt’s beloved young wife Saskia died. They had been married for less than 10 years.

Moreover, in 1636, a series of deaths began to occur in their families. In 1636, 1638, and 1640, their first three children died shortly after childbirth. In 1640, Rembrandt’s mother also died. And, during this same time period, Saskia too experienced deaths in her family, including her favorite sister. Then in 1642, Saskia died.

A marked decrease in Rembrandt’s artistic productivity occurred following Saskia’s death in 1642 (e.g., 19 etchings in 1641, eight in 1642, two in 1643, and three in 1644). Chapman (1) has noted that Rembrandt’s drawings and prints of landscapes at this time reflect his retreat to the countryside during the 1640s. And she relates this to Rembrandt’s “turning inward,” noting that 17th-century “medical books advised the troubled melancholic to seek the solitude of nature” (p. 80). Moreover, the two darkest etchings in Rembrandt’s oeuvre were created during the 1640s, i.e., Saint Jerome in a Dark Chamber (1642) and Student at a Table by Candlelight (ca. 1642, the exact date of this etching has not been established).

Thus, in 1642, when Rembrandt was working on Saint Jerome in a Dark Chamber, he had to have had an awareness of the experience of depression. (I am not making a clinical diagnosis of depression in Rembrandt on the basis of the material presented here, although this possibility cannot be ruled out.) It is obvious, however, that Rembrandt must have been going through a period of profound despair when he created Saint Jerome in a Dark Chamber. Clearly, at that time, he had to have known what the depressed mind felt like. Consequently, I feel Saint Jerome in a Dark Chamber was Rembrandt’s metaphoric portrayal of the state of his own mind, darkened by depression, turned inward, but finding no light. After many years of experience listening to depressed patients, this interpretation somehow seemed right to me when I first saw this etching—and it still does.

Further, more than 20 years later, I still find Rembrandt’s Saint Jerome in a Dark Chamber a mystery—a mystery of darkness, of shadows, of barely seen objects, of the black chamber with the bright light outside shining in the window but not penetrating the darkness. In essence, I feel that this etching portrays the mystery of the depressed mind (Rembrandt’s mind in 1642), the dark chamber into which no light can penetrate.

Address reprint requests to Dr. Schildkraut, 35 Jefferson Rd., Chestnut Hill, MA 02467. Etching was a gift to the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, from Mrs. Lydia Evans Tunnard in memory of W.G. Russell Allen. Image courtesy of the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston.

Figure 1. Saint Jerome in a Dark Chamber, 1642a

aRembrandt Harmensz. van Rijn, Dutch, 1606–1669. First state print (#61.1363): etching, drypoint, and engraving. Catalogue Raisonné: Bartsch 105 I; Hind 201 i. Platemark: 15 cm × 17.6 cm (5 7/8 in. × 6 15/16 in.). Sheet: 15.1 cm × 17.6 cm (5 15/16 in. × 6 15/16 in.). Copyright © 2003 Museum of Fine Arts, Boston.

1. Chapman HP: Rembrandt’s Self-Portraits. Princeton, NJ, Princeton University Press, 1990Google Scholar