Short-Term Use of Estradiol for Depression in Perimenopausal and Postmenopausal Women: A Preliminary Report

Abstract

OBJECTIVE: The authors examined the effect of a 4-week course of estrogen therapy on depression in perimenopausal and postmenopausal women. METHOD: Twenty-two depressed women who were either perimenopausal (N=10) or postmenopausal (N=12) received open-label treatment with transdermal 17β-estradiol (100 μg/day) for 4 weeks. The Montgomery-Åsberg Depression Rating Scale and the Beck Depression Inventory were used to assess depressive symptoms, the Greene Climacteric Scale was used to assess menopause-related symptoms, and the Clinical Global Impression (CGI) was used to assess global clinical improvement in these women at baseline and after treatment. Remission of depression was defined as a score <10 on the Montgomery-Åsberg Depression Rating Scale and a score ≤2 on the CGI at week 4. RESULTS: Remission of depression was noted in eight of the 20 women who completed the study; two of these women were postmenopausal, and six were perimenopausal. Antidepressant response was not associated with severity or subtypes of depression at study entry or with concomitant improvement in menopause-related symptoms. CONCLUSIONS: Some perimenopausal women with depression may benefit from short-term use of estrogen therapy, and its role for postmenopausal depressed women warrants further investigation. Antidepressant benefit associated with estrogen therapy may be independent of improvement in physical symptoms.

More than 1.3 million women are expected to reach menopause each year in the United States (1, 2). The menopausal transition—a period of heightened hormonal variability—is associated with the occurrence of severe vasomotor symptoms, greater risk for osteoporosis, greater sexual dysfunction (3, 4), depressive symptoms (5–7), and substantial psychosocial impairment (8).

Two double-blind placebo-controlled studies (9, 10) demonstrated significant antidepressant benefit associated with use of estrogen therapy (transdermal estradiol) in perimenopausal women with depressive disorders. However, another study (11) suggested that long-term use of estrogen therapy is associated with greater clinical risks and side effects. It thus becomes critical to identify characteristics of depressed perimenopausal and postmenopausal women who may or may not derive antidepressant benefit from estrogen therapy.

Method

The current study represents the first phase of a larger trial designed to evaluate the effects of combined estrogen therapy and antidepressant therapy in women who failed to respond to an initial 4-week course of estrogen therapy. Thirty subjects were enrolled in this initial phase; 27 of these women met initial eligibility criteria. Transvaginal ultrasounds were performed to exclude women with a thickened endometrium.

Twenty-two perimenopausal (N=10) and postmenopausal (N=12) women 42–57 years old who had DSM-IV diagnoses of major depression, minor depression, or dysthymia were enrolled in a 4-week open-label clinical trial of 100 μg/day of transdermal 17β-estradiol. Our institutional review board approved the protocol. Written informed consent was obtained from the participants after the study procedures were fully explained.

Perimenopausal status was defined as having irregular menstrual cycles (fewer than six menstrual cycles per year) and follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH) levels greater than 20 IU/liter, documenting declining ovarian function. Postmenopausal status was defined as being amenorrheic for 12 months or more or having had bilateral oophorectomy. The Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV was administered at baseline. A semistructured interview was also used to collect demographic data and menstrual and reproductive history.

Exclusion criteria included medical illness, use of psychoactive drugs in the 3 months before assessment, abnormalities on screening ultrasound, and clinical contraindications to estrogen therapy.

Depressive symptoms were assessed at study entry with the Montgomery-Åsberg Depression Rating Scale (12) and the Beck Depression Inventory. Menopause-related symptoms were evaluated with the Greene Climacteric Scale (13), which provides total scores and subscores of psychological, physical, and vasomotor symptoms (hot flashes, night sweats). The investigator and patient versions of the Clinical Global Impression (CGI) for severity were also administered.

All subjects received transdermal adhesives (Berlex Laboratories, Montville, N.J., once-weekly application) that release 100 μg of 17β-estradiol per day. Hormone assessments (FSH, estradiol), Beck Depression Inventory, Montgomery-Åsberg Depression Rating Scale, Greene Climacteric Scale, and investigator and patient versions of the CGI were repeated after 4 weeks of treatment. Remission of depression was defined as a Montgomery-Åsberg Depression Rating Scale score <10 and a CGI investigator/patient version rating ≤2 at week 4 for all depressive subtypes. A 50% or more decrease from baseline in Greene Climacteric Scale scores defined improvement of menopause-related symptoms.

Changes in Montgomery-Åsberg Depression Rating Scale, Beck Depression Inventory, and Greene Climacteric Scale scores were assessed with Wilcoxon signed-rank tests. Nonparametric procedures (Mann-Whitney tests) were used to compare Montgomery-Åsberg Depression Rating Scale and Greene Climacteric Scale scores of perimenopausal and postmenopausal women. Chi-square methods for discrete measures (or Fisher’s exact test for small samples) and nonparametric procedures (Mann-Whitney tests) for continuous measures were used to examine the relationship of demographic characteristics, menstrual history, and psychiatric history between women with or without remission of depression after treatment with estradiol. The same procedures were used to examine differences between perimenopausal and postmenopausal subgroups. Spearman correlation coefficients (rs) were calculated for Montgomery-Åsberg Depression Rating Scale and Beck Depression Inventory scores and for changes in Montgomery-Åsberg Depression Rating Scale and Greene Climacteric Scale scores and subscores from baseline to week 4. Statistical significance was established at the alpha=0.05 level for all analyses.

Results

Twenty-two women (10 perimenopausal, 12 postmenopausal), whose median age was 50 years (range=42–57), were eligible to receive treatment. Twelve (54.5%) of the women were divorced, 18 (81.8%) were working outside the home, and 16 (72.7%) had a college degree or some college education. The women’s median weight at baseline was 153 lb (range=100–285).

The 10 perimenopausal women had a median duration of amenorrhea of 5.0 months (range=0.5–11.0), a median FSH level of 56.45 IU/liter (range=20.00–64.90), and a median weight of 172.5 lb (range=100–266). The 12 postmenopausal women had a median duration of amenorrhea of 42 months (range=24–120), a median FSH level of 96 IU/liter (range=36–186), and a median weight of 144.5 lb (range=100–285).

Twelve (54.5%) of the women suffered from major depression, seven (31.8%) met criteria for minor depression, and three (13.6%) met criteria for dysthymia. Depressive symptoms were of moderate severity at baseline (median Montgomery-Åsberg Depression Rating Scale score=21, range=14–32). A significant correlation (rs=0.58, N=22, p<0.01) was noted between severity of depression assessed by study psychiatrists and that reported by the study participants (mean Beck Depression Inventory score=22.5, range=11–47).

There were no significant differences between perimenopausal and postmenopausal women with respect to demographic characteristics, reproductive history (except for duration of amenorrhea), or current DSM-IV diagnosis (p≥0.05 for all comparisons, chi-square test or Fisher’s test). In addition, perimenopausal and postmenopausal women did not differ significantly with respect to body weight (z=–0.85, p=0.40), severity of depressive symptoms determined by Montgomery-Åsberg Depression Rating Scale total scores (z=0.56, p=0.57), or menopause-related symptoms determined by Greene Climacteric Scale total scores (z=–0.92, p=0.36). As might be expected, both groups had different mean FSH levels at baseline (z=–2.81, p<0.01).

Twenty women (90.9%) completed the 4-week course of estrogen therapy. One subject discontinued treatment because of local skin irritation, and one patient was lost to follow-up. Overall, treatment was well tolerated; the most common adverse events reported were local skin irritation (N=3) and bleeding (N=2). The average weight gain after 4 weeks of estrogen therapy was 1.3 lb (SD=3.0, range=–6 to 5), a nonsignificant variation when compared with weight observed at baseline (z=–1.75, p=0.08). There were no significant differences in weight gain between perimenopausal and postmenopausal women (z=–0.84, p=0.40).

The women who completed the study had a median Montgomery-Åsberg Depression Rating Scale score of 20 (range=15–32) at study entry and 11.50 (range=1.0–31.0) at week 4 (z=–3.43, p<0.01). This improvement was consistent with that reported by the women themselves on the Beck Depression Inventory (rs=0.86, N=20, p<0.01). The improvement measured by CGI scores was also significant (p<0.01).

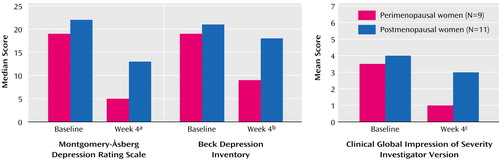

Remission of depression (Montgomery-Åsberg Depression Rating Scale score <10 and CGI investigator/patient version score ≤2) was achieved by eight of the 20 women who completed the study; only two of 11 postmenopausal women achieved remission of depression, compared with six of the nine perimenopausal women (p=0.06, Fisher’s exact test) (Figure 1). No significant differences were noted between women who did or did not achieve remission of depression regarding demographic characteristics, marital status, education, employment status, or subtypes of depression (p≥0.05 for all comparisons, chi-square or Fisher’s exact test).

Menopause-related symptoms measured with the Greene Climacteric Scale decreased significantly from baseline (median score=23.50, range=3–48) to week 4 (median score=12.50, range=1–38) (z=–3.62, p<0.01). Ten women (three postmenopausal, seven perimenopausal) had a ≥50% decrease in Greene Climacteric Scale scores after estrogen therapy. Full remission of vasomotor symptoms was achieved by seven perimenopausal and four postmenopausal women (p=0.09, Fisher’s exact test). Changes in Montgomery-Åsberg Depression Rating Scale scores were not significantly correlated with changes in Greene Climacteric Scale scores (rs=0.21, N=20, p=0.37) or changes in Greene Climacteric Scale vasomotor subscores (rs=0.08, N=20, p=0.71).

Discussion

Despite the obvious methodological limitations of this open clinical trial (e.g., absence of a placebo arm, small study group), we found a significant antidepressant effect associated with 4 weeks of estrogen therapy. Hypotheses regarding the mechanisms of early antidepressant response associated with estrogen therapy are discussed elsewhere (14, 15); these mechanisms may be different from those proposed for conventional antidepressants (16).

The significant and relatively rapid antidepressant response observed in most perimenopausal women treated with estrogen therapy is consistent with the results of a previous placebo-controlled study with transdermal estradiol (9, 10) and with an open trial with oral estradiol (17). One placebo-controlled study demonstrated a significant but more gradual response to estradiol over a 12-week course of treatment (10). If confirmed, an early antidepressant response may constitute a marker for perimenopausal depressed women who would benefit from estrogen therapy.

In the current trial, most of the postmenopausal women with depression did not respond to estrogen therapy; this finding is consistent with one large placebo-controlled study (18). In that study, however, only older postmenopausal women (mean age=62 years) were enrolled, and most of them did not have substantial vasomotor symptoms.

In our study, perimenopausal and postmenopausal women were similar at baseline with respect to age, severity of depressive symptoms, and vasomotor complaints. Perimenopausal and postmenopausal women showed satisfactory response to estradiol with respect to vasomotor symptoms; however, most postmenopausal women did not achieve an antidepressant benefit from estrogen therapy. These findings support the hypothesis that depression in perimenopausal women may constitute a distinct reproductive-cycle-associated mood disturbance that may be responsive to hormonal interventions (19, 20).

There were no significant differences between women who did and did not experience remission of depression with respect to changes in Greene Climacteric Scale scores and vasomotor subscores. This finding supports previous studies suggesting that the effect of estrogen therapy on mood may be independent of antidepressant effects mediated by alleviation of vasomotor symptoms (9, 10). Additional investigation is needed 1) to examine more completely the short-term antidepressant response to estradiol, 2) to differentiate the impact of estrogen therapy on perimenopausal and postmenopausal depressed women, and 3) to clarify the potential role of estradiol in the treatment algorithm for managing depression in perimenopausal and postmenopausal depressed women.

Received July 17, 2002; revision received Jan. 8, 2003; accepted Jan. 21, 2003. From the Perinatal and Reproductive Psychiatry Clinical Research Program and Vincent Memorial Obstetrics and Gynecology Service, Massachusetts General Hospital; and the Department of Psychiatry, Harvard Medical School. Address reprint requests to Dr. Cohen, Perinatal and Reproductive Psychiatry Clinical Research Program, Massachusetts General Hospital-Harvard Medical School, 15 Parkman St., WACC 815, Boston, MA 02114; [email protected] (e-mail). Supported by a research grant from Forest Laboratories and by a National Alliance for Research on Schizophrenia and Depression Young Investigator Award (Dr. Soares, 2001 Callaghan Investigator).

Figure 1. Depressive Symptoms and Clinical Improvement in Perimenopausal and Postmenopausal Women Assessed at Baseline and After 4 Weeks of Treatment With Estradiol

aSignificant change from baseline among perimenopausal (z=–2.66, p=0.008) and postmenopausal (z=–2.23, p=0.03) women.

bSignificant change from baseline among perimenopausal (z=–2.49, p=0.01) and postmenopausal (z=–2.40, p=0.02) women.

cSignificant change from baseline among perimenopausal women (z=–2.10, p=0.04); nonsignificant change among postmenopausal women (z=–1.66, p=0.10).

1. Burt VK, Altshuler LL, Rasgon N: Depressive symptoms in the perimenopause: prevalence, assessment, and guidelines for treatment. Harv Rev Psychiatry 1998; 6:121–132Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

2. Menopause Core Curriculum Study Guide. Cleveland, Ohio, North American Menopause Society, 2000Google Scholar

3. Research on the Menopause in the 1990s: Report of a WHO Scientific Group. World Health Organ Tech Rep Ser 1996; 866:1–107Medline, Google Scholar

4. Stone AB, Pearlstein TB: Evaluation and treatment of changes in mood, sleep, and sexual functioning associated with menopause. Obstet Gynecol Clin North Am 1994; 21:391–403Medline, Google Scholar

5. Hay AG, Bancroft J, Johnstone EC: Affective symptoms in women attending a menopause clinic. Br J Psychiatry 1994; 164:513–516Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

6. Novaes C, Almeida O, de Melo N: Mental health among perimenopausal women attending a menopause clinic: possible association with premenstrual clinic? Climacteric 1998; 1:264–270Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

7. Harlow BL, Cohen LS, Otto MW, Spiegelman D, Cramer DW: Prevalence and predictors of depressive symptoms in older premenopausal women: the Harvard Study of Moods and Cycles. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1999; 56:418–424Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

8. Schmidt PJ, Rubinow DR: Menopause-related affective disorders: a justification for further study. Am J Psychiatry 1994; 148:844–852Google Scholar

9. Schmidt PJ, Nieman L, Danaceau MA, Tobin MB, Roca CA, Murphy JH, Rubinow DR: Estrogen replacement in perimenopause-related depression: a preliminary report. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2000; 183:414–420Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

10. Soares CN, Almeida OP, Joffe H, Cohen LS: Efficacy of estradiol for the treatment of depressive disorders in perimenopausal women: a double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled trial. Arch Gen Psychiatry 2001; 58:529–534Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

11. Grady D, Wenger NK, Herrington D, Khan S, Furberg C, Hunninghake D, Vittinghoff E, Hulley S: Postmenopausal hormone therapy increases risk for venous thromboembolic disease: the Heart and Estrogen/Progestin Replacement Study. Ann Intern Med 2000; 132:689–696Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

12. Montgomery SA, Åsberg M: A new depression scale designed to be sensitive to change. Br J Psychiatry 1979; 134:382–389Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

13. Greene JG: Constructing a standard climacteric scale. Maturitas 1998; 29:25–31Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

14. Rubinow DR, Schmidt PJ, Roca CA: Estrogen-serotonin interactions: implications for affective regulation. Biol Psychiatry 1998; 44:839–850Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

15. Woolley CS: Effects of estrogen in the CNS. Curr Opin Neurobiol 1999; 9:349–354Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

16. Halbreich U, Kahn LS: Role of estrogen in the aetiology and treatment of mood disorders. CNS Drugs 2001; 15:797–817Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

17. Rasgon NL, Altshuler LL, Fairbanks L: Estrogen-replacement therapy for depression (letter). Am J Psychiatry 2001; 158:1738Link, Google Scholar

18. Morrison M: Estrogen and mood in aging women: an update, in Abstracts of the 15th Annual Meeting of the American Association of Geriatric Psychiatry. Bethesda, Md, AAGP, 2002Google Scholar

19. Schmidt PJ, Roca CA, Bloch M, Rubinow DR: The perimenopause and affective disorders. Semin Reprod Endocrinol 1997; 15:91–100Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

20. Burger HG, Dudley EC, Hopper JL, Groome N, Guthrie JR, Green A, Dennerstein L: Prospectively measured levels of serum follicle-stimulating hormone, estradiol, and the dimeric inhibins during the menopausal transition in a population-based cohort of women. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 1999; 84:4025–4030Medline, Google Scholar