Multiple Idiopathic Physical Symptoms in the ECA Study:Competing-Risks Analysis of 1-Year Incidence, Mortality, and Resolution

Abstract

OBJECTIVE: Competing-risks analysis was used to determine the 1-year longitudinal outcomes, including mortality, associated with multiple idiopathic physical symptoms in a population sample. METHOD: The authors analyzed baseline and 1-year follow-up data from the population-based NIMH Epidemiological Catchment Area Study. Multinomial logit regression was used to examine the incidence of multiple idiopathic physical symptoms, resolution of such symptoms, and related mortality among individuals in the general population, with adjustment for demographic characteristics and the presence or absence at baseline of a lifetime diagnosis of major depression, dysthymia, anxiety disorder, and alcohol abuse. Multinomial logit modeling also accounts for the impact of competing outcomes, such as survey nonresponse. RESULTS: Most of the individuals with multiple idiopathic physical symptoms recovered over the ensuing year. The incidence of multiple idiopathic physical symptoms among those without such symptoms at baseline was 1.7%. The predicted mortality among individuals with multiple idiopathic physical symptoms at baseline was higher than for individuals not having such symptoms at baseline (0.28% versus 0.18%). The higher mortality rate among those with multiple idiopathic physical symptoms at baseline persisted after adjustment for covariates and competing outcomes. CONCLUSIONS: Outcomes associated with multiple idiopathic physical symptoms vary widely. Most individuals improve over time. However, the course for a few individuals is less benign than perhaps previously thought. Further research is needed to determine the mechanisms behind increases in mortality related to multiple idiopathic physical symptoms, the predictors of poor prognosis, and whether mortality remains elevated over longer periods of follow-up.

Idiopathic physical symptoms are exceptionally common in primary care as well as subspecialty clinics. Physical symptoms account for over 400 million clinic visits in the United States alone each year, and at least one-third of the time, symptoms remain idiopathic after careful evaluation (1).

Physicians are traditionally taught to view multiple idiopathic physical symptoms as “somatization.” Somatization syndromes are thought to be chronic and disabling but less than life threatening. While considerable research has been devoted to the substantial effects of multiple idiopathic physical symptoms on health-related quality of life (2–4), there has been a dearth of research on whether or not these syndromes are associated with differences in mortality rates. Understanding the natural history of multiple idiopathic physical symptoms can offer insights to clinicians planning treatment and policy makers developing health care priorities or planning future research agendas.

The severity of multiple idiopathic physical symptoms occurs along a continuum (5), and only 0.1%–0.2% of adults in the United States have enough symptoms to satisfy diagnostic criteria for the most severe form of multiple idiopathic physical symptoms, somatization disorder (6). A much larger proportion of individuals in the general population report multiple idiopathic physical symptoms, however, and Escobar and colleagues (7) developed criteria for a less severe (“abridged”) syndrome characterized by four or more idiopathic symptoms for men and six or more for women, also known as the somatic symptom index 4/6 (SSI-4/6). Escobar et al. (4, 6) found that the SSI-4/6 criteria were met by 4.4% of U.S. adults studied. Since then, a myriad of low-threshold syndromes involving multiple idiopathic physical symptoms have been studied, and some have been used clinically. These include undifferentiated somatoform disorder (DSM-III-R), multisomatoform disorder (8), an index using three symptoms for men and five for women (SSI-3/5) (9), and chronic multisymptom illness (10). In a large multiethnic general population sample (4, 6, 7), the SSI-4/6 was associated with a higher prevalence of psychiatric disorders, especially mood and anxiety disorders, greater use of medical services, and higher levels of unemployment and days in bed, effects that persisted even after the influences of demographic factors and health status were controlled for. Rief and colleagues (9) compared several sets of criteria for multisymptom syndromes, including the DSM-III-R and DSM-IV somatization disorder criteria, the SSI-3/5, and the SSI-4/6, in patients referred for behavioral treatment. Rief et al. found a high degree of concordance across subthreshold definitions based on multiple symptoms. Escobar and colleagues (11) briefly reviewed the research findings from various studies using the SSI-4/6. They noted that the SSI-4/6 has shown robust associations, suggesting construct validity, in diverse study groups, such as primary care patients, Puerto Ricans, disaster victims, U.S. women in the community, and patients seen in medical specialty clinics for one of a wide range of “single-symptom syndromes,” such as tinnitus, chronic pelvic pain, and persistent dizziness.

We wanted to learn more about the natural history of multiple idiopathic physical symptoms, particularly their relationship to mortality, using data from the National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH) Epidemiological Catchment Area (ECA) study. An important methodological issue when determining the relationship between a health condition and a longitudinal outcome is the need to consider how the baseline condition changes over time. An outcome such as mortality reflects only one potential consequence of multiple idiopathic physical symptoms, and it is important to correct mortality figures for the occurrence of “competing” consequences (12, 13). For example, by considering survey nonresponse, the incidence of multiple idiopathic physical symptoms, and the resolution of multiple idiopathic physical symptoms as competing outcomes, one can better understand the potential impact of these factors on estimates of mortality related to multiple idiopathic physical symptoms. Therefore, in the present research we used a multivariate competing-risks model to investigate the natural history of multiple idiopathic physical symptoms and the possible linkage between such symptoms and mortality among U.S. adults.

Method

Sample and Data

Data for the present research came from the baseline and 1-year follow-up surveys of the ECA study, conducted by NIMH in the mid-1980s. These data were obtained from the public domain. All individual subject identifiers were previously removed to preserve their anonymity. The ECA study and its methods are extensively described in other publications (14–16). In brief, the ECA study was a collaborative research effort to determine the epidemiology of specific mental disorders in the United States and associated utilization of health services. The study was conducted in five geographic regions of the United States, including the New Haven (Conn.), Baltimore, St. Louis, Durham (N.C.), and Los Angeles areas. About 3,000 households and 500 institutionalized individuals were targeted for interviews at each site. Of the original 18,571 respondents (we excluded institutionalized individuals), 14,480 interviews were completed in year 1. Of the nonrespondents, 135 were reported to have died within the following year. Hence, 78.7% of the baseline respondents (including those who died) were followed up 1 year later. For the rest of the nonrespondents, the various reasons for nonresponse identified included “refusal” (1,302 persons), “ill” (three persons), and “other reasons” (2,651 persons).

Measurements

As previously noted, a number of criteria sets for subthreshold somatization have been used in epidemiological and clinical research using demographically diverse study groups (4–8, 10). Although each definition varies slightly and offers small advantages and disadvantages, all are predicated on the notion that somatization occurs along a continuum, and all are generally reliable and valid. We defined multiple idiopathic physical symptoms in accordance with the previously described definition used by Escobar and colleagues (7). Idiopathic physical symptoms were determined by using a highly structured interview, the NIMH Diagnostic Interview Schedule (DIS) (6, 17), that polls patients about 37 different physical symptoms encompassing a wide range of body regions and systems. When an interview respondent endorses a particular physical symptom, the DIS prompts with several questions that are then used to characterize the symptom as either medically explained or medically unexplained. The survival status at follow-up, dead or not, was determined by the interviewers. Survival status among nonrespondents who were unavailable because of “other reasons” (2,651 persons) was sometimes unknown. However, we did not find systematic differences between nonresponse at follow-up and covariates predicting mortality, suggesting that confounding by follow-up status was likely to be minor.

All covariates considered in the present research were obtained at the baseline survey. Table 1 presents the distributions of respondents by baseline covariates for the whole sample and for the subsample of individuals without missing data. The frequencies of the various characteristics for the effective sample agree closely with those for the whole sample.

We used four demographic characteristics as covariates: gender (male or female), age (years of age at the time of the baseline survey), marital status (currently married or other), and ethnicity (white, black, and others). To capture ethnicity, we used two dichotomous variables, white (yes or no) and black (yes or no), with “other ethnicities” serving as the reference group. In addition, we included educational attainment (total number of years in school) as a proxy for an individual’s socioeconomic status.

It is well known that several psychiatric disorders are associated with higher than average rates of mortality (18). Since we were interested in the impact of multiple idiopathic physical symptoms on mortality independent of such effects, we used lifetime diagnoses of major depression (yes or no), dysthymia (yes or no), any anxiety disorder (yes or no), and alcohol abuse (yes or no) as control variables. We also considered the possible confounding effects of some other psychiatric disorders (for example, bipolar disorder), but their inclusion in the model would not contribute any further information in the presence of the aforementioned four psychiatric disorder covariates. That is, the values of model chi-square and regression coefficients of covariates remained almost identical with and without consideration of these other psychiatric disorders.

Data Analysis

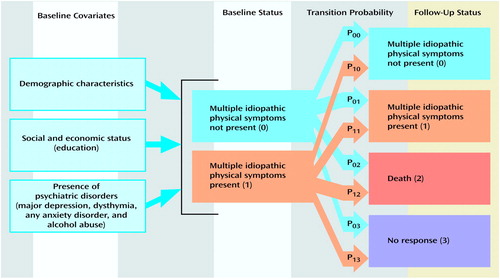

We specified a competing-risks model (12) that linked the presence of Escobar’s “abridged” criteria for multiple idiopathic physical symptoms to the following outcomes: mortality, incident multiple idiopathic physical symptoms, persistent symptoms, resolution of symptoms, or survey nonresponse. With the specification of a competing-risks framework, the mechanisms inherent in the relationship between multiple idiopathic physical symptoms and the death rate can be examined as a process of health transitions (12, 13). The proposed model consisted of eight possible transitions, defined as the change in health status between the baseline and follow-up assessments (Figure 1). The possible baseline health states were absence and presence of multiple idiopathic physical symptoms (denoted as origins 0 and 1 in Figure 1, respectively), and the four possible outcomes were absence of multiple idiopathic physical symptoms, presence of symptoms, death, and nonresponse (denoted as outcomes 0, 1, 2, and 3). Hence, there were eight possible transitions (i.e., two possible baseline states that could each make a transition to four possible outcome states). The probability of experiencing a given type of transition is denoted by Pij, where i and j refer, respectively, to the baseline state in relation to multiple idiopathic physical symptoms (i = 0, 1) and the outcome state (j = 0, 1, 2, 3).

Because of the small number of subjects with multiple idiopathic physical symptoms at baseline, we established a nested model for longitudinal outcomes; that is, the status of such symptoms at baseline (present versus not present) was treated as a covariate in the model with “multiple idiopathic physical symptoms at baseline.” The effect of the baseline state on associations between the other covariates and longitudinal outcomes regarding multiple idiopathic physical symptoms was assessed by looking for interactions between the baseline status of multiple idiopathic physical symptoms and each of the covariates. As there were four competing outcomes, multinomial logit regression was used to model them. The model covariates included the previously described nine covariates, baseline status regarding multiple idiopathic physical symptoms, and five statistically significant interaction terms (interactions of baseline status and education, baseline status and white ethnicity, baseline status and major depression, baseline status and any anxiety disorder, and baseline status and alcohol abuse). The appropriate multinomial logit model in this setting is given by  where β represents the matrix of regression coefficients to be estimated. This equation defines a given log odds as a linear function of model covariates (12).

where β represents the matrix of regression coefficients to be estimated. This equation defines a given log odds as a linear function of model covariates (12).

From our model, we calculated two sets of population estimates of the eight transition probabilities. The first set of population estimates used values of the covariates that were fixed at the weighted means for each of the two baseline states regarding multiple idiopathic physical symptoms (presence and absence). The second set of population estimates used weighted mean covariate values observed for the entire sample. The first set of estimates yielded population estimates, that is, estimates for the U.S. adult population as represented by the weighted ECA sample. The second set of estimates permitted a population comparison of transition probabilities for individuals with and without baseline multiple idiopathic physical symptoms while simultaneously adjusting for the potentially confounding effects of covariates (i.e., adjusted population estimates). Hence, the effects of multiple idiopathic physical symptoms on mortality could be effectively analyzed. Because these probabilities were derived from the multinomial logit model, we used the delta method (19) to calculate the converted standard error of each transition probability and its corresponding p value. Given that the sum of a set of transition probabilities must equal one, the values of all probabilities within a set are considered statistically significant if at least one of the probabilities is significant at alpha=0.05.

Results

The bivariate association between baseline status regarding multiple idiopathic physical symptoms and mortality was statistically significant (full sample: χ2=6.32, df=1, p=0.02; sample excluding nonrespondents: χ2=5.60, df=1, p=0.02). Table 2 presents the distribution of the respondents by baseline and 1-year status in regard to multiple idiopathic physical symptoms. Of those who did not meet our criteria for multiple idiopathic physical symptoms at baseline (16,816 persons), about 0.6% died within the period of follow-up; 96.6% of the respondents completing the 1-year follow-up (including the deceased subjects) did not have multiple idiopathic physical symptoms 1 year later. Of the respondents completing the 1-year follow-up, 2.6% developed multiple idiopathic physical symptoms within the 1-year period. About two in 10 individuals without baseline multiple idiopathic physical symptoms failed to respond to the survey at 1-year follow-up. Compared with those without baseline multiple idiopathic physical symptoms, individuals with multiple idiopathic physical symptoms were about twice as likely to die and were slightly less likely to be nonrespondents at the 1-year follow-up. The probability of recovering from multiple idiopathic physical symptoms within the 1-year period was sizable. More than one-half (59.5%) of those completing the 1-year follow-up who had multiple idiopathic physical symptoms at baseline had recovered from the syndrome 1 year later. These actual values describe the sample, while subsequent figures use multinomial logit modeling to generate population estimates. Sample values may differ considerably from population values predicted from statistical modeling.

Table 3 shows the two sets of population estimates of the eight transition probabilities, derived from the multinomial logit model. Since the dependent variable of a multinomial logit analysis consists of a series of log odds (12), interpretation of the regression coefficients and odds ratios is less than intuitive (13). Accordingly, these coefficients and odds ratios, available on request, are not presented here. Instead, we present the previously described population and adjusted population estimates of transition probabilities (Table 3). Estimated mortality was higher among those with multiple idiopathic physical symptoms at baseline than among those without such symptoms (0.28% versus 0.18%) (z=2.42, N=17,953, p=0.02). This elevation in estimated mortality persisted after adjustment for differences between groups in major depression, dysthymia, anxiety disorders, alcohol abuse, and demographic characteristics, as shown by the second set of population estimates (0.42% versus 0.18%) (z=5.09, N=17,953, p<0.0001).

Table 3 shows the estimated probability that a U.S. adult would undergo no transition in status regarding multiple idiopathic physical symptoms from the baseline survey to the 1-year follow-up (0.7747 for subjects without multiple idiopathic physical symptoms at baseline and 0.3196 for the smaller group with such symptoms at baseline). The estimated probability of developing multiple idiopathic physical symptoms over the period in a respondent who did not have such symptoms at baseline was approximately 0.0174 (equivalent to an estimated 1-year incidence of 1.74 per 100 person-years; z=6.68, N=17,953, p<0.0001), while the estimated probability of recovery among the respondents at 1 year who had had multiple idiopathic physical symptoms at baseline was 0.5000 (equivalent to an estimated 1-year resolution rate of 50 per 100 person-years; z=66.99, N=17,953, p<0.0001). Among respondents with multiple idiopathic physical symptoms at baseline, the estimated probability of being lost to follow-up a year later was 0.1775 (z=1.77, N=17,953, p=0.08) compared to an estimated probability of 0.2061 among those without multiple idiopathic physical symptoms at baseline (z=1.01, N=17,953, p=0.32). Because at least one transition probability in each probability set was statistically significant, all these probabilities were considered statistically meaningful. These estimated probabilities were essentially unchanged after adjustment for major depression, dysthymia, any anxiety disorder, alcohol abuse, and group demographic differences, as shown by the adjusted probability estimates (demonstrated by the second set of population estimates in Table 3).

Discussion

Several limitations of our analysis should be noted. First, differences in mortality between respondents with and without multiple idiopathic physical symptoms were small, and therefore, misclassification of death, particularly in the group of follow-up nonrespondents, could confound the relationship of multiple idiopathic physical symptoms to mortality. Second, although multinomial logit regression accounts for nonresponse in the estimation of the association between multiple idiopathic physical symptoms and competing outcomes, we cannot eliminate the possibility of nonresponse bias. Third, given the panel data available for this analysis, we used logistic regression to model determinants of outcome. This procedure does not account for the amount of time that elapsed before the outcomes occurred. If the exact timing of an outcome (e.g., death) is available, then a hazard-rate approach would be more appropriate. Fourth, the sample was followed only for 1 year. A longer period of follow-up would allow greater elucidation of mortality patterns over time. Finally, some might question the relevance of data collected almost two decades ago. While this is a limitation, we know of no direct evidence suggesting changes in the occurrence of multiple idiopathic physical symptoms over the past two decades. The ECA survey continues to be among the most frequently cited epidemiological surveys of psychiatric illness and perhaps the only one to involve a comprehensive etiological assessment of such a wide range of physical symptoms in a population-based sample.

In spite of these limitations, we found a modest but meaningful and statistically significant relationship between multiple idiopathic physical symptoms and subsequent mortality. The relationship persisted and was perhaps even strengthened after adjustment for potential confounding due to major depression, dysthymia, any anxiety disorder, alcohol abuse, and various demographic characteristics, therefore suggesting a substantial and independent impact of multiple idiopathic physical symptoms on mortality. Although the 1-year risk of death rates was low (0.28% versus 0.18%), over an extended period these mortality differences might lead to important population differences (e.g., at a constant rate, over a decade mortality would reach 2.8% among individuals with multiple idiopathic physical symptoms versus 1.8% among those without such symptoms). We cannot assume, however, that rates or differences remain stable over time, and therefore, population-based studies allowing more extended follow-up are necessary.

Future research should explore the possible mechanisms by which multiple idiopathic physical symptoms could lead to increased mortality. A number of explanatory pathways seem plausible, and many or all may be operative. First, multiple idiopathic physical symptoms may sometimes be unrecognized manifestations of a progressive disease (20). Although symptoms were classified as medically explained or unexplained in the ECA survey, information regarding comorbid medical illness at baseline was not obtained. This explanation, if operative, would appear to occur only rarely among those suffering with multiple idiopathic physical symptoms, because we found that over one-half of those with multiple idiopathic physical symptoms were recovered 1 year later. This is consistent with findings from existing studies suggesting that individuals with idiopathic symptoms seldom manifest serious and previously occult disease on subsequent follow-up (1).

A second potential explanation for greater mortality among those with multiple idiopathic physical symptoms involves comorbidity with many mental disorders (5, 21, 22). Mortality may be mediated by some combination of disabling symptoms, impaired coping, and one or more coexisting mental disorders that leads to increases in death by accidental and nonaccidental means. However, even after we controlled for a number of these disorders, the relationship between multiple idiopathic physical symptoms and mortality only strengthened, suggesting that multiple idiopathic physical symptoms represent an independent mortality risk factor.

Third, the observed difference in mortality may be a function of altered health behaviors consequent to the onset of multiple idiopathic physical symptoms. The presence of physical symptoms may usher in the development of such adverse health behaviors as smoking, drinking, and lack of exercise. For example, Walker and colleagues (23) found that childhood adversity was associated with multiple idiopathic physical symptoms and with behaviors associated with increased health risk. The influence of such behaviors on health is increasingly well known and may help explain the observed association between multiple idiopathic physical symptoms and a higher mortality rate (24, 25).

Fourth, a higher mortality rate among individuals with multiple idiopathic physical symptoms may occasionally occur from the iatrogenic impact of aggressive biomedical management, such as unnecessary and invasive surgery and diagnostic testing, as well as the adverse effects of medications used to treat symptoms (26, 27).

Significant cultural, racial, and ethnic differences in the relationship between multiple idiopathic physical symptoms and mortality may exist (28). These factors may affect such issues as symptom reporting, health-related behaviors, and the seeking of help for physical symptoms. We adjusted our estimates for differences in available demographic characteristics, such as ethnicity, marital status, and education. However, because of the relatively small number of deaths occurring over the follow-up period, we were unable to reliably ascertain the specific impact of ethnic differences on the relationship between multiple idiopathic physical symptoms and mortality. This should be the specific focus of future national and cross-national epidemiological research.

Finally, we used a competing-risks model as a way of broadening research on the relationship between multiple idiopathic physical symptoms and mortality. The use of similar statistical modeling techniques can broaden the awareness of dynamic processes involved in health outcomes associated with multiple idiopathic physical symptoms. For instance, a competing-risks model can be used to examine the possible influence of nonresponse bias on the relationship between multiple idiopathic physical symptoms and mortality.

In sum, our results confirm the important health impact of multiple idiopathic physical symptoms on those who suffer from them. The fact that multiple idiopathic physical symptoms have an important effect on functioning (29), distress (30), and mortality suggests that more efforts are needed to study the ways such symptoms alter health and health behaviors. Determinants of poor prognosis and effective clinical management strategies should be investigated. Perhaps most important, the lens through which many clinicians view multiple idiopathic physical symptoms and their patients who suffer from them requires careful assessment. Elevated morbidity and mortality rates among these individuals challenge our heretofore largely biomedical sense of such patients as simply “worried well” who suffer from “nondisease.”

|

|

|

Received Aug. 9, 2000; revisions received Jan. 19 and July 11, 2001; accepted Dec. 18, 2001. From the Deployment Health Clinical Center, Walter Reed Army Medical Center, Washington, D.C.; the Department of Psychiatry, F. Edward Hebert School of Medicine, Uniformed Services University of the Health Sciences; and the Department of Neuropsychiatry, Walter Reed Army Institute of Research, Washington, D.C. Address reprint requests to Dr. Engel, Department of Psychiatry, Uniformed Services University of the Health Sciences, Bethesda, MD 20814; [email protected] (e-mail). The ideas expressed in this article are the private views of the authors and do not reflect the official policy or position of the Uniformed Services University of the Health Sciences, Walter Reed Army Medical Center, the Department of the Army, the Department of Defense, or the U.S. government.

Figure 1. Competing-Risks Model of Transitions in Status of Multiple Idiopathic Physical Symptoms Between Baseline and Follow-Up

1. Kroenke K: Symptoms and science: the frontiers of primary care research. J Gen Intern Med 1997; 12:509-510Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

2. Anderson JS, Ferrans CE: The quality of life of persons with chronic fatigue syndrome. J Nerv Ment Dis 1997; 185:359-367Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

3. Buchwald D, Umali P, Umali J, Kith P, Pearlman T, Komaroff AL: Chronic fatigue and the chronic fatigue syndrome: prevalence in a Pacific Northwest health care system. Ann Intern Med 1995; 123:81-88Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

4. Escobar JI, Golding JM, Hough RL, Karno M, Burnam MA, Wells KB: Somatization in the community: relationship to disability and use of services. Am J Public Health 1987; 77:837-840Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

5. Katon W, Lin E, Von Korff M, Russo J, Lipscomb P, Bush T: Somatization: a spectrum of severity. Am J Psychiatry 1991; 148:34-40Link, Google Scholar

6. Swartz M, Landerman R, George LK, Blazer DG, Escobar JI: Somatization disorder, in Psychiatric Disorders in America: The Epidemiologic Catchment Area Study. Edited by Robins LN, Regier DA. New York, Free Press, 1991, pp 220-257Google Scholar

7. Escobar JI, Rubio-Stipec M, Canino GJ, Karno M: Somatic symptom index (SSI): a new and abridged somatization construct. J Nerv Ment Dis 1989; 177:140-146Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

8. Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, deGruy FV III, Hahn SR, Linzer M, Williams JB, Brody D, Davies M: Multisomatoform disorder: an alternative to undifferentiated somatoform disorder for the somatizing patient in primary care. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1997; 54:352-358Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

9. Rief W, Heuser J, Mayrhuber E, Stelzer I, Hiller W, Fichter MM: The classification of multiple somatoform symptoms. J Nerv Ment Dis 1991; 184:680-687Crossref, Google Scholar

10. Fukuda K, Nisenbaum R, Stewart G, Thompson WW, Robin L, Washko RM, Noah DL, Barrett DH, Randall B, Herwaldt BL, Mawle AC, Reeves WC: Chronic multisymptom illness affecting Air Force veterans of the Gulf War. JAMA 1998; 280:981-988Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

11. Escobar JI, Waitzkin H, Silver RC, Gara M, Holman A: Abridged somatization: a study in primary care. Psychosom Med 1998; 60:466-472Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

12. Allison PD: Survival Analysis Using the SAS System: A Practical Guide, 2nd ed. Cary, NC, SAS Institute, 1995Google Scholar

13. Liu X, Liang J, Muramatsu N, Sugisawa H: Transitions in functional status and active life expectancy among older people in Japan. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci 1995; 50:S383-S394Google Scholar

14. Robins LN, Regier DA (eds): Psychiatric Disorders in America: The Epidemiologic Catchment Area Study. New York, Free Press, 1991Google Scholar

15. Regier DA, Myers JK, Kramer M, Robins LN, Blazer DG, Hough RL, Eaton WW, Locke BZ: The NIMH Epidemiologic Catchment Area Program: historical context, major objectives, and study population characteristics. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1984; 41:934-941Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

16. Eaton WW, Holzer CE III, Von Korff M, Anthony JC, Helzer JE, George L, Burnam A, Boyd JH, Kessler LG, Locke BZ: The design of the Epidemiologic Catchment Area surveys: the control and measurement of error. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1984; 41:942-948Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

17. Robins LN, Helzer JE, Croughan J, Ratcliff KS: The National Institute of Mental Health Diagnostic Interview Schedule: its history, characteristics, and validity. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1981; 38:381-389Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

18. Simon GE, VonKorff M: Suicide mortality among patients treated for depression in an insured population. Am J Epidemiol 1998; 147:155-160Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

19. Littell RC, Milliken GA, Stroup WW, Wolfinger RD: SAS System for Mixed Models. Cary, NC, SAS Institute, 1996Google Scholar

20. Mace CJ, Trimble MR: Ten-year prognosis of conversion disorder. Br J Psychiatry 1996; 169:282-288Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

21. Katon W, Russo J: Chronic fatigue syndrome criteria: a critique of the requirement for multiple physical complaints. Arch Intern Med 1992; 152:1604-1609Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

22. Russo J, Katon W, Sullivan M, Clark M, Buchwald D: Severity of somatization and its relationship to psychiatric disorders and personality. Psychosomatics 1994; 35:546-556Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

23. Walker EA, Unutzer J, Rutter C, Gelfand A, Saunders K, VonKorff M, Koss MP, Katon W: Costs of health care use by women HMO members with a history of childhood abuse and neglect. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1999; 56:609-613Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

24. Meng L, Maskarinec G, Lee J, Kolonel LN: Lifestyle factors and chronic diseases: application of a composite risk index. Prev Med 1999; 29:296-304Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

25. Lantz PM, House JS, Lepkowski JM, Williams DR, Mero RP, Chen J: Socioeconomic factors, health behaviors, and mortality: results from a nationally representative prospective study of US adults. JAMA 1998; 279:1703-1708Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

26. Lazarou J, Pomeranz BH, Corey PN: Incidence of adverse drug reactions in hospitalized patients: a meta-analysis of prospective studies. JAMA 1998; 279:1200-1205Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

27. Fisher ES, Welch HG: Avoiding the unintended consequences of growth in medical care: how might more be worse? JAMA 1999; 281:446-453Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

28. Ono Y, Janca A, Asaia M (eds): Somatoform Disorders: A Worldwide Perspective. New York, Springer-Verlag, 1999Google Scholar

29. Gureje O, Simon GE, Ustun TB, Goldberg DP: Somatization in cross-cultural perspective: a World Health Organization study in primary care. Am J Psychiatry 1997; 154:989-995Link, Google Scholar

30. Simon GE, VonKorff M: Somatization and psychiatric disorder in the NIMH Epidemiologic Catchment Area study. Am J Psychiatry 1991; 148:1494-1500Link, Google Scholar