Mental Health Care Quality Under Managed Care in the United States: A View From the Health Employer Data and Information Set (HEDIS)

Abstract

OBJECTIVE: This study examined the rates and correlates of mental health care performance measures in the Health Employer Data and Information Set (HEDIS). METHOD: For all 384 health maintenance organizations (HMOs) participating in the HEDIS program of the National Committee for Quality Assurance during 1999, analyses examined the rates of compliance with five mental health care performance measures and their association with general medical care quality, public reporting, and HMO finances. RESULTS: The mean rate of mental health care performance was 48.0%, compared with 69.2% for non-mental-health care domains. In multivariate models adjusted for plan characteristics, scores for worse quality of non-mental-health domains, failure to report data publicly, and low medical-loss ratio (proportion of revenues spent on clinical care) all predicted poor mental health care performance. CONCLUSIONS: Better general medical care, transparency of reporting, and commitment of fiscal resources to clinical care predicted better mental health care performance for U.S. HMOs.

The Health Employer Data and Information Set (HEDIS) is the most widely used health plan “report card,” rating health plans that cover 90% of Americans enrolled in health maintenance organizations (HMOs) (1). It is also the set of quality indicators most commonly used by purchasers in selecting and rating health plans (2). Thus, performance on this report card can provide important insight into plan quality as it is currently measured and reported in the U.S. health care marketplace.

This study examines mental health care performance on the HEDIS report card during 1999. The results are intended to shed light on the rates and correlates of mental health care quality in U.S. HMOs.

Method

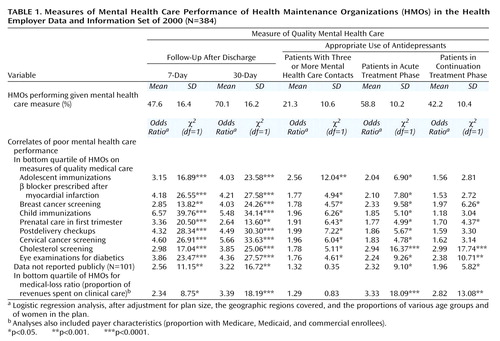

The current study used data for all plans participating in the HEDIS 2000 program of the National Center for Quality Assurance, which comprises data collected during the 1999 calendar year (3). The report card includes the five following mental health care quality measures: 1) percentage of members hospitalized for a mental disorder who had an ambulatory visit with a mental health care provider within 7 and 2) 30 days of hospital discharge, 3) effective treatment in the acute phase (ongoing medication treatment in the 3-month period after a new depressive episode), 4) effective continuation treatment (ongoing medication treatment in the 6 months after a new depressive episode), and 5) optimal practitioner contacts (at least three follow-up mental health care visits in the 3 months after a new depressive episode).

Multivariate equations modeled the association between the bottom quartile of performance on each mental health care quality measure and 1) the bottom quartile of performance for each of nine indicators of general (i.e., non-mental-health care) performance, 2) the plans’ willingness to release their quality data publicly, and 3) the bottom quartile of performance for medical-loss ratio, the fraction of a plan’s premium revenues that are paid out in claims (i.e., financial “losses”), a proxy for the degree to which a plan prioritizes clinical care (4).

All analyses included adjustment for the number of plan enrollees, geographic regions covered, and the proportions of various age groups and of women in the plan (5). Analyses of the medical-loss ratio further adjusted for the proportion of Medicare, Medicaid, and commercially insured enrollees.

Results

A total of 384 plans, covering 73 million enrollees nationwide, submitted data to National Center for Quality Assurance. These figures represent 90.0% of all individuals enrolled in U.S. HMOs and 67.6% of all U.S. HMOs, as reported by the InterStudy group, which collects national data using annual surveys and state-derived data (6). Characteristics of plans participating in HEDIS were similar to those of HMOs nationwide, with the exception that they had a lower proportion of Medicaid enrollees (5.7% versus 13.3%); therefore, the findings should be extended with caution to the managed Medicaid sector. The mean rate of compliance with the five mental health care measures presented in Table 1 was 48.0%, substantially lower than the mean compliance rate of 69.2% for the nine non-mental-health care domains.

Poor performance on four of the five quality measures (all but antidepressant treatment in the continuation phase) was consistently associated with poor general plan performance (Table 1). Although mental and non-mental-health care measures were highly correlated, they did not substitute for each other; poor performance on one or more of the non-mental-health care measures provided only a 52.5% sensitivity and a 22.5% specificity for predicting a poor rating on at least one of the mental health care measures.

The 101 plans that chose not to release their data publicly performed substantially worse on the mental health care indicators. Plans in the lowest quartile for medical-loss ratio—that is, with the lowest proportion of premium revenues paid out in claims—were 2.3 to 3.4 times as likely to perform worse on four of the five measures of mental health care quality (Table 1).

Discussion

Mental health performance of HMOs on the HEDIS measures was considerably poorer than quality on general medical care indicators. Plans that performed poorly on mental health care quality domains were significantly more likely to perform poorly on the non-mental-health care indicators, although the two domains were clearly distinct and did not substitute for one another. Failure to report quality data and lower medical-loss ratios consistently predicted worse mental health care performance.

Given the factors that distinguish mental health care from other medical services—disproportionate benefit limits (7–9) and frequent “carving out” of those benefits from other services (10, 11)—it was striking how consistently poor performance on these measures was associated with poor plan quality on non-mental-health care measures. The fact that depression for patients participating in HMOs is frequently managed by primary care providers may partly explain the link between mental health care and general medical quality in these organizations. However, even in cases in which care is managed by a separate behavioral health organization, a health plan can influence quality of mental health care by the nature of the contract, including the use of performance standards and the degree of risk sharing (12, 13).

Plans that did not release their quality data were substantially more likely to perform poorly on the mental health care quality measures than plans that made their data publicly available. This phenomenon was not unique to mental health services; failure to release data publicly is one of the strongest and most consistent predictors of poor performance on HEDIS (1). In part, this may reflect a rational decision by poorly performing plans not to subject their data to public scrutiny. However, the findings may also be mediated by the possibility that accountability drives quality: plans whose data is made public have a strong incentive to improve the care they deliver.

Finally, a low medical-loss ratio was correlated with poor performance on four of five measures, suggesting a potential link between an HMO’s relative expenditures on clinical services and the quality of mental health care it provides. The medical-loss ratio is only a limited proxy for plan finances (4), and HEDIS only collects financial data for HMOs, rather than for the mental health carve-out plans they may use. Therefore, the study’s findings suggest the need for further research into this relationship within managed behavioral organizations, using the medical-loss ratio in conjunction with other more fine-grained measures of plan finances (14).

Several important limitations should be noted. First, HEDIS covers only a limited set of domains of mental health care quality that might be assessed under more idealized research conditions (15, 16). More complete assessments of mental health care quality under managed care should include data about diagnoses other than depression, detail about the appropriateness of dosing of antidepressants, information about other modalities of treatment (e.g., psychotherapy), and measures of clinical outcomes.

Second, report cards may create an incentive for plans to disproportionately allocate resources toward measured domains rather than other potentially important areas (17, 18). This possibility speaks to the importance of selecting a broad range of performance indicators and of using measures that are in and of themselves appropriate targets for quality improvement.

Finally, the majority of behavioral health care in U.S. HMOs is carved out to managed behavioral health organizations (13). This study did not have access to data about which plans carve out their mental health care and, for those who do, the financial and structural details about who provides those mental health services. More work is needed to understand the rates and predictors of quality within managed behavioral health organizations to better inform the decisions of purchasers in choosing managed behavioral health organizations and in developing contracts with the organizations that can ensure optimal quality of mental health care for enrollees.

The study suggests that there is considerable room for improvement in both the quality of mental health services and in how that quality is measured. The fact that mental health care quality and other domains of medical care go hand in hand suggests the importance of studying and working to improve these domains in conjunction with one another.

|

Received May 24, 2001; revisions received Aug. 29 and Nov. 13, 2001; accepted Nov. 25, 2001. From the Departments of Psychiatry and Public Health, Yale University, New Haven, Conn.; and the Office of Research, National Center for Quality Assurance, Washington, D.C. Address reprint requests to Dr. Druss, 950 Campbell Ave./182, West Haven, CT 06516; [email protected] (e-mail). Funded in part by NIMH grant MH-01556. The authors thank Gregory Pawlson, M.D., for his help with the article.

1. The State of Managed Care Quality 2000. Washington, DC, National Center for Quality Assurance, 2000Google Scholar

2. Hibbard JH, Jewett JJ, Legnini MW, Tusler M: Choosing a health plan: do large employers use the data? Health Aff (Millwood) 1997; 16(6):172-180Google Scholar

3. Thompson JW, Bost J, Ahmed F, Ingalls CE, Sennett C: The NCQA’s quality compass: evaluating managed care in the United States. Health Aff (Millwood) 1998; 17(1):152-158Google Scholar

4. Robinson JC: Use and abuse of the medical loss ratio to measure health plan performance. Health Aff (Millwood) 1997; 16(4):176-187Google Scholar

5. Zaslavsky AM, Hochheimer JN, Schneider EC, Cleary PD, Seidman JJ, McGlynn EA, Thompson JW, Sennett C, Epstein AM: Impact of sociodemographic case mix on the HEDIS measures of health plan quality. Med Care 2000; 38:981-992Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

6. Lauer TM, Boese AE, Barua S, Mohr CA: HMO Industry Report 10.2. Excelsior, Minn, InterStudy, 2000Google Scholar

7. Frank RG, Koyanagi C, McGuire TG: The politics and economics of mental health “parity” laws. Health Aff (Millwood) 1997; 16(4):108-119Google Scholar

8. Sturm R, Pacula RL: Datapoints: mental health parity and employer-sponsored health insurance in 1999-2000, I: limits. Psychiatr Serv 2000; 51:1361Link, Google Scholar

9. Pacula RL, Sturm R: Datapoints: mental health parity and employer-sponsored health insurance in 1999-2000, II: copayments and coinsurance. Psychiatr Serv 2000; 51:1487Link, Google Scholar

10. Frank RG, Huskamp HA, McGuire TG, Newhouse JP: Some economics of mental health “carve-outs.” Arch Gen Psychiatry 1996; 53:933-937Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

11. Sturm R: Tracking changes in behavioral health services: how have carve-outs changed care? J Behav Health Serv Res 1999; 26:360-371Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

12. Frank RG, McGuire TG, Newhouse JP: Risk contracts in managed mental health care. Health Aff (Millwood) 1995; 14(3):50-64Google Scholar

13. Garnick DW, Horgan CM, Hodgkin D, Merrick EL, Goldin D, Ritter G, Skwara KC: Risk transfer and accountability in managed care organizations’ carve-out contracts. Psychiatr Serv 2001; 52:1502-1509Link, Google Scholar

14. Born PH, Simon CJ: Patients and profits: the relationship between HMO financial performance and quality of care. Health Aff (Millwood) 2001; 20(2):167-174Google Scholar

15. Young AS, Klap R, Sherbourne CD, Wells KB: The quality of care for depressive and anxiety disorders in the United States. Arch Gen Psychiatry 2001; 58:55-61Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

16. Wells KB, Schoenbaum M, Unutzer J, Lagomasino IT, Rubenstein LV: Quality of care for primary care patients with depression in managed care. Arch Fam Med 1999; 8:529-536Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

17. Casalino LP: The unintended consequences of measuring quality on the quality of medical care. N Engl J Med 1999; 341:1147-1150Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

18. Epstein AM: Rolling down the runway: the challenges ahead for quality reporting. JAMA 1998; 279:1691-1696Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar