Personality Factors Associated With Dissociation: Temperament, Defenses, and Cognitive Schemata

Abstract

OBJECTIVE: The purpose of this study was to investigate temperamental, psychodynamic, and cognitive factors associated with dissociation. METHOD: Fifty-three subjects with DSM-IV-defined depersonalization disorder and 22 healthy comparison subjects were administered the Dissociative Experiences Scale, the Tridimensional Personality Questionnaire, the Defense Style Questionnaire, and the Schema Questionnaire. RESULTS: Subjects with depersonalization disorder demonstrated significantly greater harm-avoidant temperament, immature defenses, and overconnection and disconnection cognitive schemata than comparison subjects. Within the group of subjects with depersonalization disorder, dissociation scores significantly correlated with the same variables. CONCLUSIONS: Particular personality factors may render individuals more vulnerable to dissociative symptoms. Risk factors associated with dissociative disorders merit further study.

The relationship between dissociative disorders and trauma is well established. However, individuals with seemingly comparable traumas may differ greatly in the extent to which they dissociate, and it has become increasingly apparent in recent years that various factors in addition to the actual trauma play a role in the development of trauma-related psychopathologies. A stress-diathesis model has been proposed for both posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) and dissociative disorders, as only about 25% of exposed individuals develop PTSD and the proportion who develop dissociative disorders is not known (1, 2).

PTSD risk factors have been identified, but much less is known about factors predisposing to dissociative symptoms; high hypnotizability or suggestibility may be one risk factor (2). In a study examining the relationship between personality and dissociation in general psychiatric patients and healthy subjects, dissociation scores were predicted by the character traits of low self-directedness and high self-transcendence but not by temperament traits (3). In a community sample, mature defenses were found to correlate with low dissociation scores (4). A twin study failed to identify a genetic contribution to pathological dissociation, but, again, a general population sample rather than a sample of patients with dissociative disorders was studied (5).

We were interested in examining personality factors associated with dissociation. Such personality traits might predispose traumatized individuals toward developing or maintaining dissociative symptoms, or, conversely, trauma and dissociation might contribute to the fixation of certain personality traits. Personality can be conceptualized as a mélange of heritable temperament and experience-shaped character, although this model is oversimplified because both temperament and character are probably partly determined by complex variations in genotypes and neurochemical profiles and partly modifiable (6, 7).

In this study we examined depersonalization disorder, one of the major dissociative disorders, for which a link to childhood interpersonal trauma has been shown (8). Regarding temperament, we hypothesized that individuals prone to behavioral inhibition would be more likely to “shut down” and dissociate when traumatized. With regard to character we used a psychodynamic model and a cognitive model and hypothesized that more primitive defenses and cognitive schemata reflecting major disruptions in attachment would be associated with dissociation.

Method

Fifty-three subjects with DSM-IV-defined depersonalization disorder and 22 healthy comparison subjects were consecutively recruited from several depersonalization research protocols for which written informed consent was obtained. Subjects were evaluated by using the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Dissociative Disorders (9). Healthy comparison subjects were free of dissociative disorders, other lifetime axis I disorders assessed by the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Axis I Disorders (10), and axis II disorders assessed by the Structured Interview for DSM-IV Personality (11). All subjects completed the Dissociative Experiences Scale (12), a 28-item self-report trait measure of dissociation, and a depersonalization subscore of the Dissociative Experiences Scale was also calculated (13).

Temperament was measured by using Cloninger’s Tridimensional Personality Questionnaire (14), a 100-item self-administered instrument that yields three temperament dimensions. Novelty seeking is the tendency to seek out novel cues, reward dependence is the tendency to strongly respond to and seek out rewards, and harm avoidance is the tendency to respond strongly to aversive stimuli and show behavioral inhibition.

Defenses were measured by using Bond’s revised 88-item version of the Defense Style Questionnaire (15), which has been factor analyzed into three levels of defenses (16). Mature defenses such as sublimation and anticipation reflect highly functional adaptation. Neurotic superego-type defenses such as undoing and reaction formation are less adaptive. Immature defenses such as projection and acting out result in denial of reality and poor adaptation.

Cognitive schemata were measured by using the Schema Questionnaire, a 205-item self-report instrument that yields three higher-order factors (17). Cognitive schemata are enduring structures at the core of an individual’s self-concept that develop during early relationships with significant others. Disconnection schemata reflect defectiveness and emotional inhibition and subsume themes of abuse, neglect, and deprivation. Overconnection schemata involve impaired autonomy with themes of dependency, vulnerability, and incompetence. Exaggerated standards schemata reflect self-sacrifice, perfectionism, and exaggerated self-expectations.

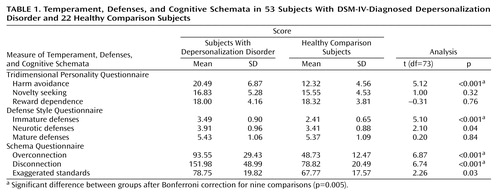

Thus, the study examined a total of nine variables, three from each instrument (Table 1). Between-group comparisons employed Student’s t tests, Bonferroni-corrected for nine comparisons. Within the group of subjects with depersonalization disorder, we computed Pearson’s correlations between dissociation scores and personality variables, applying a conservative 0.01 level of significance.

Results

The two groups did not differ in age (mean age of the subjects with depersonalization disorder was 34.38, SD=10.21, versus mean=29.82, SD=7.06, for the comparison subjects) (t=1.91, df=73, n.s.) or gender (25 of the subjects with depersonalization disorder were women, compared with 13 women in the group of healthy subjects) (χ2=0.88, df=1, n.s.). Dissociation scores were higher in the group of subjects with depersonalization disorder (mean=21.5, SD=12.7, versus mean=3.9, SD=3.2) (t=6.40, df=73, p<0.001), as were depersonalization scores (mean=43.6, SD=20.6, versus mean=2.6, SD=3.2) (t=9.23, df=73, p<0.001).

Table 1 shows that the scores for harm avoidance, immature defenses, and overconnection and disconnection cognitive schemata were significantly greater in the subjects with depersonalization disorder than in the comparison subjects. Within the group of subjects with depersonalization disorder, dissociation scores significantly correlated with harm avoidance (r=0.36, df=51, p=0.009), immature defenses (r=0.61, df=51, p<0.001), disconnection (r=0.49, df=51, p<0.001), and overconnection (r=0.41, df=51, p<0.001). Depersonalization scores were significantly correlated with overconnection (r=0.40, df=51, p=0.003). All correlations among harm avoidance, immature defenses, overconnection, and disconnection were significant (p<0.01), with the exception of the correlation between harm avoidance and immature defenses.

Discussion

These findings support the hypothesis that several personality factors are associated with pathological dissociation. Specifically, harm-avoidant temperament, immature defenses, and overconnection and disconnection cognitive schemata were highly prevalent in the subjects with depersonalization disorder and, furthermore, were quantitatively related to the severity of dissociation.

We are not able to determine on the basis of our findings whether these personality correlates of dissociation play a causal role in its genesis, contribute to its perpetuation over time, or become fixed aspects of personality as a result of trauma and dissociation. A longitudinal design is needed to address such temporal relationships.

Other limitations include the use of self-report instruments, the absence of comparison psychiatric groups, and the inclusion of a single dissociative diagnosis. However, the validity of the instruments used is widely established, and the findings are robust. The Defense Style Questionnaire immature factor includes 12 defenses, and dissociation is just one, represented by three of 46 questions; therefore, the finding of prevalent immature defenses in the group of subjects with depersonalization disorder is not tautological. The poorly investigated topic of dissociative diatheses merits further study.

|

Received Nov. 27, 2000; revisions received April 13 and July 6, 2001; accepted Aug. 23, 2001. From the Department of Psychiatry, Mount Sinai School of Medicine. Address reprint requests to Dr. Simeon, Psychiatry Box 1229, Mount Sinai School of Medicine, One Gustave L. Levy Pl., New York, NY 10029-6574; [email protected] (e-mail). Supported in part by NIMH grant MH-055582 (Dr. Simeon).

1. Breslau N, Davis GC, Andreski P, Peterson E: Traumatic events and posttraumatic stress disorder in an urban population of young adults. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1991; 48:216-222Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

2. Butler LD, Duran REF, Jasiukaitis P, Koopman C, Spiegel D: Hypnotizability and traumatic experience: a diathesis-stress model of dissociative symptomatology. Am J Psychiatry 1996; 153(July festschrift suppl):42-63Google Scholar

3. Grabe H-J, Spitzer C, Freyberger HJ: Relationship of dissociation to temperament and character in men and women. Am J Psychiatry 1999; 156:1811-1813Abstract, Google Scholar

4. Romans SE, Martin JL, Morris E, Herbison GP: Psychological defense styles in women who report childhood sexual abuse: a controlled community study. Am J Psychiatry 1999; 156:1080-1085Abstract, Google Scholar

5. Waller NG, Ross CA: The prevalence and biometric structure of pathological dissociation in the general population: taxometric and behavior genetic findings. J Abnorm Psychol 1997; 106:499-510Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

6. Comings DE, Gade-Andavolu R, Gonzalez N, Wu S, Muhleman D, Blake H, Mann MB, Dietz G, Saucier G, MacMurry JP: A multivariate analysis of 59 candidate genes in personality traits: the Temperament and Character Inventory. Clin Genet 2000; 58:375-385Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

7. Cravchik A, Goldman D: Neurochemical individuality: genetic diversity among human dopamine and serotonin receptors and transporters. Arch Gen Psychiatry 2000; 57:1105-1114Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

8. Simeon D, Guralnik O, Schmeidler J, Sirof B, Knutelska M: The role of childhood interpersonal trauma in depersonalization disorder. Am J Psychiatry 2001; 158:1027-1033Link, Google Scholar

9. Steinberg M: Interviewer’s Guide to the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Dissociative Disorders (SCID-D). Washington, DC, American Psychiatric Press, 1993Google Scholar

10. First MB, Spitzer RL, Gibbon M, Williams JBW: Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Axis I Disorders (SCID). New York, New York State Psychiatric Institute, Biometrics Research, 1995Google Scholar

11. Pfohl B, Blum N, Zimmerman M: Structured Interview for DSM-IV Personality: SIDP-IV. Iowa City, University of Iowa, Department of Psychiatry, 1995Google Scholar

12. Bernstein EM, Putnam FW: Development, reliability, and validity of a dissociation scale. J Nerv Ment Dis 1986; 174:727-735Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

13. Simeon D, Guralnik O, Gross S, Stein DJ, Schmeidler J, Hollander E: The detection and measurement of depersonalization disorder. J Nerv Ment Dis 1998; 186:536-542Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

14. Cloninger CR: A systematic method for clinical description and classification of personality variants. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1987; 44:573-588Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

15. Bond M: Defense Style Questionnaire, in Empirical Studies of Ego Mechanisms of Defense. Edited by Vaillant GE. Washington, DC, American Psychiatric Press, 1986, pp 146-152Google Scholar

16. Andrews G, Pollock C: The determination of defense style by questionnaire. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1989; 46:455-460Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

17. Schmidt NB, Young JE, Telch MJ: The Schema Questionnaire: investigation of psychometric properties and the hierarchical structure of a measure of maladaptive schemas. Cogn Ther Res 1995; 19:295-321Crossref, Google Scholar