Efficacy of Sertraline in the Long-Term Treatment of Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder

Abstract

OBJECTIVE: Obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD) typically begins early in life and has a chronic course. Despite the need for long-term treatment, the authors found no placebo-controlled studies that have examined the relapse-prevention efficacy of maintenance therapy. METHOD: Patients who met criteria for response after 16 and 52 weeks of a single-blind trial of sertraline were randomly assigned to a 28-week double-blind trial of 50–200 mg/day of sertraline or placebo. Primary outcomes after the double-blind trial were full relapse, dropout due to relapse or insufficient response, or acute exacerbation of OCD symptoms. RESULTS: Of 649 patients at baseline, 232 completed 52 weeks of the single-blind trial and met response criteria. Among the 223 patients in the double-blind phase of the study, sertraline had significantly greater efficacy than placebo on two of three primary outcomes: dropout due to relapse or insufficient clinical response (9% versus 24%, respectively) and acute exacerbation of symptoms (12% versus 35%). Sertraline resulted in improvement in quality of life during the initial 52-week trial and continued improvement, significantly superior to placebo, during the subsequent 28-week double-blind trial. Long-term treatment with sertraline was well tolerated. Over the entire study period, less than 20% of the patients stopped treatment because of adverse events. CONCLUSIONS: Sertraline demonstrated sustained efficacy among patients responding to treatment and was generally well tolerated during the 80-week study. During the study’s last 28 weeks, sertraline demonstrated greater efficacy than placebo in preventing dropout due to relapse or insufficient clinical response and acute exacerbation of OCD symptoms.

One-year prevalence estimates for obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD), based on community surveys, have been reported to range from 0.4% to 2.3% (1), with lifetime prevalence estimates ranging as high as 2.6% (2). OCD typically has an early age at onset, with a course of illness that is among the most chronic of the psychiatric disorders. In a study of 560 patients (3), 85% reported a continuous course of illness, 10%, a deteriorating course, and only 2%, an episodic course marked by full remissions lasting 6 months or more. Surveys of both community and treatment populations (4–6) found the diagnosis of OCD to be associated with significant impairment in perceived functioning and quality of life.

A substantial body of placebo-controlled studies has established the safety and efficacy of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor (SSRI) antidepressants for the acute treatment of OCD, although only slightly more than 30%–60% of the subjects who participated in the controlled trials met response criteria (7–12). Moreover, although SSRIs are usually well tolerated, a minority of patients stop treatment because of gastrointestinal, sexual, or other side effects (7–12). Given the early onset of OCD, it is important to note that sertraline, fluvoxamine, and fluoxetine have demonstrated significant efficacy in the treatment of OCD in children and adolescents (13–15). Few placebo-controlled studies, however, have investigated the usefulness of SSRIs, once a short-term response has been achieved, in preventing exacerbation of obsessive-compulsive symptoms or relapse of the illness.

The ability of sertraline to maintain improvement in OCD patients after short-term treatment has been demonstrated in a double-blind placebo-controlled study (16) in which responders to 12 weeks of fixed doses (50, 100, or 200 mg/day) of sertraline or placebo were assigned to a double-blind fixed-dose trial for an additional 40 weeks. At the 52-week endpoint, mean scores on all four primary outcome measures—the Yale-Brown Obsessive Compulsive Scale, the National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH) Global Obsessive Compulsive Scale, and the Clinical Global Impression (CGI) severity-of-illness and improvement scales—revealed significantly greater improvement (p<0.005) for the pooled sertraline group than for the placebo group.

Fifty-one of the patients who originally participated in the double-blind trial of sertraline or placebo continued to receive open-label sertraline treatment for up to a total of 2 years (17). The Yale-Brown Obsessive Compulsive Scale scores of these patients decreased by a mean of 11.4 during the first year and by a mean of 3.2 during the second year, which suggests that efficacy was not only maintained but that modest additional improvement occurred.

The present study augments the results of that long-term treatment study with a design intended to assess the efficacy of sertraline in preventing patient relapse during a 28-week double-blind trial of sertraline or placebo in patients who had achieved a sustained response during 52 weeks of single-blind sertraline therapy.

Method

Study Design

This was an 80-week study conducted at 21 sites in the United States. The subjects were outpatients 18 years of age and older who had a DSM-III-R-defined diagnosis of OCD. At study entry, the patients completed a 1-week drug-free washout period. If they continued to meet study criteria at the end of the washout period (baseline), they entered 16 weeks of single-blind treatment with flexible doses of sertraline. All medication administered throughout the 80-week study period was administered from blister packs holding 50-mg tablets of sertraline (or identical placebo tablets). The patients took 50 mg/day of sertraline during weeks 1 through 4. Patients who failed to respond satisfactorily to treatment could have their dose titrated up to 100 mg/day during weeks 5 and 6 in the absence of dose-limiting adverse events, to 150 mg/day during weeks 7 and 8, and to the maximum dose of 200 mg/day after 8 weeks. In the presence of dose-limiting adverse events, the dose could be reduced in 50-mg/day decrements to a minimum of 50 mg/day. Patients who failed to meet response criteria by the end of 16 weeks of sertraline treatment were withdrawn from the study.

Patients who met the response criteria at the end of week 16 continued with the same dose of single-blind sertraline treatment for an additional 36 weeks; assessments were performed every 4 weeks. For the patients who were not taking the maximum permissible daily dose, an increase in dose was permitted if the investigator thought it might improve the patient’s response. Patients who met relapse criteria on any one of these assessments were scheduled for an assessment 2 weeks later. If they continued to meet the relapse criteria by the 2-week visit, they were scheduled for a third relapse assessment after an additional 2 weeks; if they still met the relapse criteria, they were dropped from the study.

The patients who continued to meet the response criteria at the end of week 52 were randomly assigned to a 28-week double-blind trial with either sertraline or matching placebo. For the patients randomly assigned to sertraline treatment, their daily dose of sertraline as of week 52 was maintained. Until the end of week 56, the patients randomly assigned to placebo took the same number of tablets daily as they had during week 52, but the sertraline dose was blindly decreased by 50 mg/day every 3 days by use of planned substitution of placebo tablets into the blister packs at weeks 53 and 54. Thus, from the end of week 54, these patients took only placebo tablets.

Study Patients

The study patients were recruited by means of newspaper and radio advertisements and from the clinical practices of the investigators. We included male and female outpatients 18 years of age and older who met DSM-III-R criteria for obsessive-compulsive disorder as determined by the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-III-R (SCID-P) (18). At baseline, the patients had to have a minimum total score of 20 on the Yale-Brown Obsessive Compulsive Scale (19, 20) and a score of at least 7 on the NIMH Global Obsessive Compulsive Scale (21). Patients were excluded from study entry for the following reasons:

1. Having a total score on the 24-item Hamilton Depression Rating Scale (22) of 17 or higher.

2. Being a woman who was currently pregnant or lactating or of childbearing potential and not using a medically accepted form of contraception.

3. Having a current diagnosis of organic mental disorder, major depression, bipolar disorder, Tourette’s syndrome, or a severe axis II personality disorder or a principle diagnosis of trichotillomania, somatoform disorder, panic disorder, social phobia, or generalized anxiety disorder.

4. Having a current or verified past diagnosis of schizophrenia, delusional disorder, or other psychosis.

5. Having a DSM-III-R-defined diagnosis of alcohol or substance abuse and/or dependence in the past 6 months

6. Having a positive urine drug screening test.

7. Having any medical contraindications to treatment with sertraline.

8. Having a history or evidence of malignancy other than excised basal cell carcinoma.

9. Having an acute or unstable medical illness.

10. Participating in an investigational drug study within 28 days before entering the study.

11. Taking sertraline within 2 months of study entry, not responding to an adequate trial of sertraline in the past, or participating in an investigational study of sertraline.

12. Concomitantly using any psychotropic medication (other than chloral hydrate for sleep).

13. Receiving concurrent behavior therapy for OCD.

14. Receiving treatment with an monoamine oxidase inhibitor within 2 weeks, a depot neuroleptic within 6 months, fluoxetine within 5 weeks, or a neuroleptic, anxiolytic, or antidepressant on a daily basis in the 2 weeks before the first administration of sertraline.

15. Having a test of liver function showing a level at more than twice the upper limit of normal on the first day of the washout period.

16. Being illiterate, or, in the investigator’s judgment, unable or unlikely to follow the study protocol for the full 80 weeks.

The study protocol and forms giving the patients’ informed consent were approved by the institutional review board at each study site. Before study entry, written informed consent was obtained from each subject.

Efficacy Measures

The patients were evaluated at baseline and at subsequent study visits, which occurred weekly for the first 4 weeks and then biweekly until the end of week 16. From week 16 on, the patients were seen and evaluated every 4 weeks unless they met the relapse criteria, in which case an additional assessment was scheduled in 2 weeks. The investigator completed at baseline and at each study visit the Yale-Brown Obsessive Compulsive Scale, the NIMH Global Obsessive Compulsive Scale, the CGI (23) severity-of-illness scale, and, after the baseline trial, the CGI improvement scale. A patient rating, the Quality of Life Enjoyment and Satisfaction Questionnaire (24), a scale assessing 16 aspects of quality of life and functioning, was completed at study entry and at study assessments after 16, 52, and 80 weeks of the trial or at study dropout. The investigators specified and agreed to the following definitions during protocol development:

Response

A “response” was defined as occurring when patients’ total scores decreased 25% or more from their baseline (at entry into the single-blind trial) levels on the Yale-Brown Obsessive Compulsive Scale and their CGI improvement scale score was 3 or lower (at least “minimal” improvement). (Although a decrease in score of 25% or more would not be accepted as a “response” criterion in studies involving diabetes, this criterion in commonly used in trials of OCD pharmacotherapy. Its acceptance is testimony to the need for better OCD treatments.) The patients had to meet response criteria by the end of week 16 to continue in the single-blind trial and by the end of week 52 to be randomly assigned to the double-blind phase of the study.

Relapse

After week 16, “relapse” required that a patient meet three criteria during three consecutive visits at 2-week intervals (a period of 1 month):

1. Have an increase in score of 5 points or more (from the week-16 score) on the Yale-Brown Obsessive Compulsive Scale.

2. Have a total score on the Yale-Brown Obsessive Compulsive Scale of 20 or more.

3. And at least a 1-point increase in score on the CGI improvement scale.

We elected to require 1 month of substantial worsening because OCD patients often experience fluctuations in the intensity of their symptoms. In addition, changes in a patient’s environment may exacerbate their symptoms; e.g., a patient with a fear of germs may have more symptoms if a friend with an acute infection visits his or her home. To differentiate routine oscillations in clinical status from relapse, we used repeated evaluations over a 1-month interval. The patients whose symptoms resolved continued in the study; the patients whose symptoms continued to meet the relapse criteria were classified as relapsed and were automatically removed from the study. The patients could also be removed from the study before completing the 1-month observation period if the investigator believed that it was in the patient’s best interest.

During the double-blind study phase, the definition of relapse was based on the same numeric change in score on the Yale-Brown Obsessive Compulsive Scale and the same change in score on the CGI improvement scale from the end of the single-blind trial (week 52). In many cases the strict protocol definition of relapse was not satisfied because the patient (or investigator) decided, as a result of insufficient clinical response, to drop out of (or drop the patient from) the study immediately at a regular assessment and, consequently, before the three relapse-defining visits.

Acute exacerbation of OCD

In order to describe on a finer scale the outcomes during the double-blind study phase, the investigators wished to have a less stringent, more acute criterion of symptom worsening than the criteria that defined relapse. This endpoint was termed “acute exacerbation of OCD” and used as its reference point the patients’ scores at the end of week 52, which was the baseline for the double-blind phase. Acute exacerbation of OCD was defined as an increase in score of 5 points or more to a minimum of a score of 20 on the Yale-Brown Obsessive Compulsive Scale or an increase in score of at least 2 points on the CGI improvement scale. The patients who met criteria for acute exacerbation of OCD were not automatically released from the study for this reason.

Safety Assessments

A medical history and physical examination were performed on the patients at study entry; a physical examination was repeated at weeks 52 and 80 or when a patient dropped out of the study. Blood pressure, heart rate, and weight were obtained at each study visit.

Both observed and volunteered adverse events were recorded, including date of onset of symptoms, duration, severity, causality, and outcome. ECG testing was performed at study entry and at the end of treatment weeks 2, 10, 16, 32, 52, and 80 (or at study dropout). Laboratory testing was performed at a central laboratory, and blood samples were obtained at each study site at study entry (day 1 of washout) and at the end of treatment weeks 2, 10, 16, 32, 52, 64, and 80 (or at study dropout). Laboratory tests consisted of standard hematology and blood chemistry panels, a urinalysis, and beta human chorionic gonadotropin pregnancy testing for all women of child-bearing potential. Blood samples for T3 uptake and T4 level and urine for a drug screening were obtained only at day 1 of the drug washout.

Statistical Analysis

A Kaplan-Meier survival analysis was used to estimate the probability of relapse, study discontinuation due to relapse or insufficient clinical response, or acute exacerbation of OCD as a function of time in the presence of censored observations. Time to relapse, time to dropout due to relapse or insufficient clinical response, and time to acute exacerbation of OCD were compared between groups by use of the log-rank test. Observed rates of relapse, dropout due to relapse or insufficient clinical response, and acute exacerbation of OCD were also evaluated as rates by dividing the number of patients experiencing the event by the total number of patients who took the study drug and provided efficacy data. These rates were compared between groups by using continuity-adjusted chi-square tests. Treatment comparisons of changes in efficacy scores from baseline to endpoint (with the last observation carried forward) were performed by using the Wilcoxon rank-sum test (normal approximation with a continuity correction of 0.5). Quality of Life Enjoyment and Satisfaction Questionnaire scores were calculated as a percent of the maximum score of 70 for the first 14 items of the scale. All tests of hypotheses were based on the SAS NPAR1WAY procedure. Statistical tests were two-tailed and were conducted at the 0.05 significance level.

Results

Patient Group and Disposition

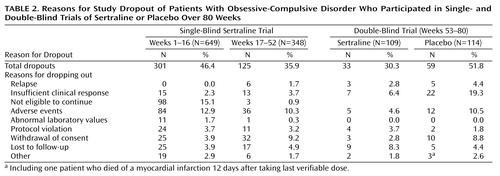

Figure 1 shows the disposition of the 649 patients who enrolled in the study during the course of the single-blind and double-blind trials. The patients were nearly equally divided by gender at study baseline; at entry into the double-blind phase, men slightly outnumbered women in both groups (Table 1). At study entry, all the patients reported that their OCD was chronic (mean=21 years, SD=12), with a moderate or greater degree of illness severity, as reflected in their scores on the Yale-Brown Obsessive Compulsive Scale and the NIMH Global Obsessive Compulsive Scale. At the end of week 52 (baseline of the double-blind phase), there were no significant descriptive differences between the patients who were randomly assigned to treatment with sertraline and those who were assigned to placebo.

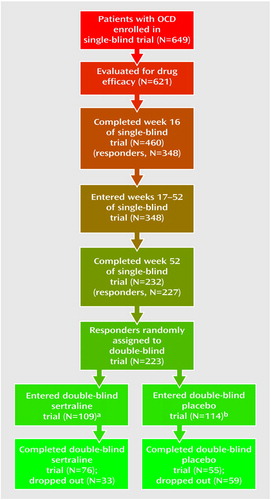

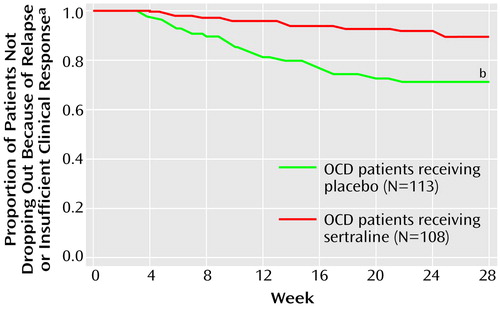

By the end of 16 weeks of the single-blind sertraline trial, 301 of the patients (46%) had stopped participating for a variety of reasons (Table 2). Among them, 98 patients (15% of those who entered the study) were dropped as per protocol because of failure to meet response criteria. When patients in the 52-week, single-blind sertraline trial were analyzed, adverse events were the most common reason for study discontinuation (N=120, 18%), followed by ineligibility to continue (did not meet response criteria, N=101, 16%), and withdrawal of consent (N=57, 9%).

During the 28-week double-blind trial, more patients taking placebo (N=27, 24%) than taking sertraline (N=10, 9%) stopped participating because of relapse or insufficient clinical response (χ2=7.47, df=1, p=0.006) (Table 2). In the double-blind phase, there were no statistically significant differences between the two groups regarding study discontinuation for adverse events (placebo: N=12, 10.5%; sertraline: N=5, 4.6%), being lost to follow-up (placebo: N=5, 4.4%; sertraline: N=9, 8.3%), and withdrawal of consent (placebo: N=10, 8.8%; sertraline: N=3, 2.8%) (Table 2). Seven patients receiving sertraline and 16 patients receiving placebo met relapse criteria at one visit and were dropped from the study at that visit for insufficient clinical response.

Clinical Response

Single-blind trial

There was consistent and progressive improvement in all four investigator-rated efficacy measurements (Table 3) throughout the 52 weeks of the single-blind sertraline trial. This was due in part to some patients dropping out for lack of efficacy. This symptomatic improvement was associated with improved quality of life, as measured by the patient-rated Quality of Life Enjoyment and Satisfaction Questionnaire (higher scores reflect better quality of life) (Table 3).

Double-blind trial

Sertraline demonstrated a significant advantage over placebo (Figure 2) according to two of the three primary outcome endpoints: study discontinuation due to relapse or insufficient clinical response (sertraline: N=10, 9%, versus placebo: N=27, 24%) and acute exacerbation of OCD symptoms (sertraline, N=13, 12%, versus placebo, N=40, 35%).

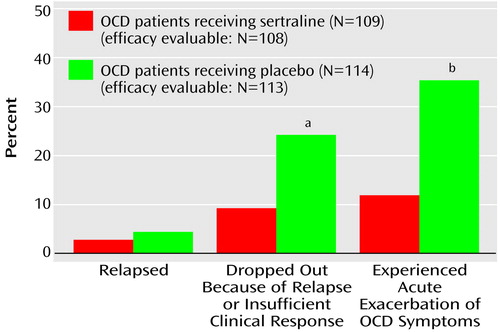

Figure 3 shows the Kaplan-Meier survival probability estimate of the cumulative probability of not dropping out of the study because of relapse or insufficient clinical response for patients receiving sertraline or placebo over the 28-week double-blind trial. The difference significantly favored the patients taking sertraline. Analogous Kaplan-Meier estimates for an acute exacerbation of OCD symptoms provided a difference that significantly favored sertraline (log-rank test, χ2=18.95, df=1, p=0.0001).

The third outcome criterion, the cumulative probability of remaining relapse-free, was higher for patients receiving sertraline (N=105, 97%) than for patients receiving placebo (N=108, 96%). The small number of patients who met the stringent relapse criteria (three visits, including the first visit and subsequent visits at 2-week intervals, in which patients met the criteria for scores on the Yale-Brown Obsessive Compulsive Scale and the CGI scale) (three of 108 patients taking sertraline and five of 113 patients receiving placebo) resulted in a finding of no significant difference between groups (log-rank test, χ2=0.90, df=1, p=0.34).

Sertraline was associated with sustained symptom improvement during the double-blind study phase, compared to the patients at the end of the 52-week single-blind phase. In an analysis of patients in the last-observation-carried-forward group at endpoint (Table 3), the sertraline group experienced a significantly smaller adjusted mean increase in scores on the Yale-Brown Obsessive Compulsive Scale from the baseline of the double-blind trial (adjusted for scores at week 52) than did the placebo group. Similar results, statistically significantly favoring sertraline over placebo, were also found on analysis of scores of the last-observation-carried-forward group at endpoint on the NIMH Global Obsessive Compulsive Scale and the CGI severity-of-illness and improvement scales.

During the double-blind trial, sertraline provided a modest but significant advantage over placebo in the associated score on the Quality of Life Enjoyment and Satisfaction Questionnaire. On average, patients had improvement in their quality of life scores during the 52-week single-blind study phase. During the 28-week double-blind trial, the patients who were randomly assigned to sertraline continued to show gains in their mean score, while those who were randomly assigned to placebo had a decrease in their mean quality-of-life rating. For change in score on the Quality of Life Enjoyment and Satisfaction Questionnaire from baseline to endpoint of the double-blind trial, the difference between groups was statistically significant (Wilcoxon rank-sum test, z=2.58, p=0.007). The difference favoring sertraline was also statistically significant on the score on item 16 of Quality of Life Enjoyment and Satisfaction Questionnaire, the patient’s overall satisfaction (Wilcoxon rank-sum test, z=3.82, p<0.001).

Tolerability

The mean dose of sertraline at the double-blind baseline (week 52) was 183 mg/day. At week 56, after we tapered the placebo group’s sertraline at the rate of 50 mg/day every 3 days until those patients stopped taking it, the mean doses of sertraline were 189 mg/day for the sertraline group and 177 mg/day of placebo equivalent for the placebo group. At the study endpoint, the sertraline dose was 187 mg/day, and the placebo equivalent was 174 mg/day. Sertraline treatment was well tolerated at these doses. Among the patients who completed the trial, the prevalence of ongoing adverse effects and the incidence of new adverse effects diminished during the course of the single-blind sertraline trial. During the first 16 weeks of the study, the most frequently reported (incidence of 20% or more) adverse events were insomnia, headache, nausea, ejaculatory failure (male patients only), somnolence, and diarrhea. From weeks 17 through 52, diarrhea, headache, and upper respiratory infection only occurred in 20% or more of the patients. During the double-blind phase, the only adverse events that occurred with an incidence of 10% or more in the sertraline-treated patients were upper respiratory infection, headache, and malaise. The only notable difference in the rates of adverse events was the increase in dizziness and depression reported in the patients receiving placebo.

Sertraline was generally well tolerated during the 80 weeks of treatment. Over this interval, less than 20% of the patients stopped participating in the study because of adverse events. During the 28-week double-blind phase, dropouts due to adverse events occurred at a higher rate among the patients who had been randomly assigned to receive placebo (N=12, 10.5%) than among those receiving sertraline (N=5, 4.6%) (Table 2). No patient was dropped from the study at any point because of laboratory test abnormalities, nor was there a statistically significant difference between the sertraline and placebo groups in the incidence of any treatment-emergent abnormalities in ECGs, vital signs, or laboratory test results or in clinically significant changes in weight.

Discussion

The results of this study clearly demonstrate the efficacy of a 28-week, double-blind sertraline trial in maintaining the clinical benefits achieved during a 52-week single-blind trial in outpatients suffering from chronic OCD with symptoms of moderate to marked severity. Furthermore, during the double-blind phase, sertraline was significantly more effective than placebo at two of the three endpoints for judging clinical outcomes: study discontinuation due to relapse or insufficient clinical response and acute exacerbation of OCD symptoms. Sertraline and placebo groups did not differ significantly on the third outcome indicator, a strictly defined relapse, probably because of its very low incidence (<5% overall) during the 28-week double-blind phase. This low relapse rate may be partly due to our having required that relapse criteria be met at three consecutive visits over a 4-week period. The low relapse rate may also reflect a sustained benefit of 52 weeks of therapy with sertraline, even after drug discontinuation, although uncontrolled studies (25, 26) have suggested rates of relapse in the range of 40%–60% after 1 year for patients who dropped out of clomipramine or SSRI treatment. These studies, however, were marked by a much shorter duration of treatment before drug discontinuation than in the present study.

The fact that only about one-third of the patients treated with placebo experienced an acute exacerbation of OCD symptoms within the 28-week double-blind study period is notable. Again, this may reflect the sustained benefit of 52 weeks of drug therapy. Alternately, since we did not make regular inquiries, some placebo patients, sensing the onset of worsened symptoms, may have engaged in self-designed behavior therapy guided by one the many self-help books available. Finally, the study’s limit of 6 months of observation for the placebo patients means that additional research is needed to determine the rates at which OCD symptom exacerbation occurs during longer periods of treatment with effective medication.

In addition to the investigator-rated efficacy measures, the patients’ self-rated quality of life, as measured by the Quality of Life Enjoyment and Satisfaction Questionnaire, improved significantly during the single-blind phase of the study. From the baseline of the double-blind trial, the patients randomly assigned to receive sertraline reported a small but measurable increase in quality of life scores over 28 weeks, while the patients randomly assigned to receive placebo reported a loss from their previous gain in scores, resulting in a statistically significant difference between the two groups. Thus, continued sertraline treatment was associated with diminished effects of OCD symptoms on patients’ everyday lives.

Sertraline was generally well tolerated during the 80 weeks of treatment. Less than 20% of the patients withdrew from the study because of adverse events. There was a progressive reduction in the frequency of reported adverse events over the course of the single-blind trial, although some of this decrease was due to study discontinuation by patients who were intolerant of sertraline. Most adverse events occurring during the double-blind phase were mild to moderate in intensity, despite a mean sertraline dose of 187 mg/day at study endpoint. Given the chronicity of OCD and the need for long-term therapy in the majority of patients, the tolerability of sertraline is clinically important. A favorable side effect profile is especially important for patients with OCD, since as many as 20% of patients refuse study medication because of fears of possible side effects (25).

Although this study demonstrated positive results regarding the efficacy of sertraline, alterations in the study design could benefit future investigations. The most obvious is the protocol definition of “relapse.” It was important to differentiate a true relapse from routine oscillations in clinical status. However, our requirement of three visits and a total of 4 weeks’ participation to confirm relapse was probably too conservative. A confirmatory evaluation after a patient meets relapse criteria at a single visit is desirable, but one additional visit at a 1- or 2-week interval might be adequate. If the patient did not meet relapse criteria at the confirmatory visit, he or she would be retained in the study.

Although the length of the 1-year single-blind portion of the study undoubtedly contributed to patient attrition for reasons other than worsening of OCD symptoms, a design incorporating a shorter single-blind study phase would not have told us whether a 1-year trial is of adequate duration to assess SSRI treatment of OCD. A 1-year, open-label initiation period is a study design alternative that might promote greater retention of patients and would accurately reflect what occurs in clinical practice. Future research should investigate how long maintenance treatment should continue, the optimal dose of medication to prevent relapse, and the role of supplementary behavior therapy in preventing relapse.

In conclusion, the current study examined the effects over 6 months of double-blind placebo-controlled medication maintenance after 12 months of single-blind sertraline treatment. The results confirm the clinical efficacy of sertraline in achieving and sustaining response over 18 months. The results also demonstrate the lack of prominent discontinuation symptoms after sertraline cessation and confirm its effectiveness in preventing acute exacerbation of OCD symptoms and treatment discontinuation due to relapse or insufficient clinical response.

|

|

|

Presented in part at the 152nd annual meeting of the American Psychiatric Association, Washington, D.C., May 15–20, 1999, and at the 39th annual meeting of the New Clinical Drug Evaluation Units, Boca Raton, Fla., June 1–4, 1999. Received Aug. 8, 2000; revision received June 11, 2001; accepted July 31, 2001. From the Department of Psychiatry, Stanford University; the Research Department, Hillside Hospital, Glen Oaks, NY; and the Department of Psychiatry, Albert Einstein College of Medicine, Bronx, N.Y. Address reprint requests to Dr. Koran, OCD Clinic, Rm. 2363, Department of Psychiatry, 401 Quarry Rd., Stanford, CA 94305; [email protected] (e-mail). Supported by a grant from Pfizer, Inc. The authors thank the following investigators for their help: Jeffrey T. Apter, M.D., Robert J. Bielski, M.D., Jonathan Davidson, M.D., Brian B. Doyle, M.D., Robert L. DuPont, M.D., James Ferguson, M.D., Wayne Goodman, M.D., Carl Houck, M.D., Ari Kiev, M.D., Peter D. Londborg, M.D., R. Bruce Lydiard, Ph.D., M.D., Dennis Munjack, M.D., Bharat Nakra, M.D., Philip Ninan, M.D., Steven Rasmussen, M.D., Jeffrey Simon, M.D., Ward Smith, M.D., Stephen Stahl, M.D., Ph.D., and John Zajecka, M.D.

Figure 1. Stages in Single- and Double-Blind Trials of Sertraline or Placebo Over 80 Weeks for Patients With Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder (OCD)

aEfficacy evaluable subjects: N=108.

bEfficacy evaluable subjects: N=113.

Figure 2. Rates of Poor Clinical Response Among Patients With Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder (OCD) During a 28-Week Double-Blind Trial of Sertraline and Placebo

aSignificant difference between groups (χ2=7.47, df=1, p=0.006).

bSignificant difference between groups (χ2=15.27, df=1, p=0.001).

Figure 3. Time to Dropout Due to Relapse or Insufficient Clinical Response for Patients With Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder (OCD) During a 28-Week Double-Blind Trial of Sertraline and Placebo

aKaplan-Meier survival probability.

bSignificant difference between groups (log-rank test, χ2=10.87, df=1, p=0.001).

1. Koran LM: Obsessive-Compulsive and Related Disorders in Adults: A Comprehensive Clinical Guide. Cambridge, UK, Cambridge University Press, 1999, p 49Google Scholar

2. Weissman MM, Bland RC, Canino GJ, Greenwald S, Hwu HG, Lee CK, Newman SC, Oakley-Browne MA, Rubio-Stipec M, Wickramaratne PJ, Wittchen HU, Yeh EK (The Cross National Collaborative Group): The cross national epidemiology of obsessive compulsive disorder. J Clin Psychiatry 1994; 55(suppl 3):5-10Google Scholar

3. Rasmussen SA, Eisen JL: The epidemiology and clinical features of obsessive compulsive disorder. Psychiatr Clin North Am 1992; 15:743-758Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

4. Koran LM, Thienemann ML, Davenport R: Quality of life for patients with obsessive-compulsive disorder. Am J Psychiatry 1996; 153:783-788Link, Google Scholar

5. Hollander E, Kwon JH, Stein DJ, Broatch J, Rowland CT, Himelein CA: Obsessive-compulsive and spectrum disorders: overview and quality of life issues. J Clin Psychiatry 1996; 57(suppl 8):3-6Google Scholar

6. A Gallup Study of Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder Sufferers. Princeton, NJ, Gallup Organization, 1990Google Scholar

7. Greist J, Chouinard G, DuBoff E, Halaris A, Kim SW, Koran L, Liebowitz M, Lydiard RB, Rasmussen S, White K, Sikes C: Double-blind parallel comparison of three dosages of sertraline and placebo in outpatients with obsessive-compulsive disorder. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1995; 52:289-295Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

8. Bisserbe J-C, Lane RM, Flament MF (Franco-Belgian OCD Study Group): A double-blind comparison of sertraline in outpatients with obsessive-compulsive disorder. Eur Psychiatry 1997; 12:82-93Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

9. Zohar J, Judge R: Paroxetine versus clomipramine in the treatment of obsessive-compulsive disorder. Br J Psychiatry 1996; 169:468-474Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

10. Koran LM, McElroy SL, Davidson JRT, Rasmussen SA, Hollander E, Jenike M: Fluvoxamine versus clomipramine for obsessive-compulsive disorder: a double-blind comparison. J Clin Psychopharmacol 1996; 16:121-129Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

11. Tollefson GD, Rampey AH, Potvin JH, Jenike MA, Rush AJ, Dominguez RA, Koran LM, Shear K, Goodman W, Genduso LA: A multicenter investigation of fixed-dose fluoxetine in the treatment of obsessive-compulsive disorder. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1994; 51:559-567Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

12. Goodman WK, Price LH, Delgado PL, Palumbo J, Krystal JH, Nagy LM, Rasmussen SA, Heninger GR, Charney DS: Specificity of serotonin reuptake inhibitors in the treatment of obsessive-compulsive disorder: comparison of fluvoxamine and desipramine. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1990; 47:577-585Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

13. March JS, Biederman J, Wolkow R, Safferman A, Mardekian J, Cook EH, Cutler NR, Dominguez R, Ferguson J, Muller B, Riesenberg R, Rosenthal M, Sallee FR, Wagner KD: Sertraline in children and adolescents with obsessive-compulsive disorder: a multicenter randomized controlled trial. JAMA 1998; 280:1752-1756Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

14. Riddle MA, Claghorn J, Gaffney G: A controlled trial of fluvoxamine for OCD in children and adolescents (abstract). Biol Psychiatry 1996; 39:568Crossref, Google Scholar

15. Riddle MA, Scahill L, King RA, Hardin MT, Anderson GM, Ort SJ, Smith JC, Leckman JF, Cohen DJ: Double-blind trial of fluoxetine and placebo in children and adolescents with obsessive-compulsive disorder. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 1992; 31:1062-1069Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

16. Greist JH, Jefferson JW, Kobak KA, Chouinard G, DuBoff E, Halaris A, Kim SW, Koran LM, Liebowitz MR, Lydiard RB, McElroy S, Mendels J, Rasmussen S, White K, Flicker C: A 1 year double-blind placebo-controlled fixed dose study of sertraline in the treatment of obsessive-compulsive disorder. Int Clin Psychopharmacol 1995; 10:57-65Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

17. Rasmussen SA, Hackett E, DuBoff E, Greist JH, Halaris A, Koran LM, Liebowitz M, Lydiard RB, McElroy S, Mendels J, O’Connor K: A 2-year study of sertraline in the treatment of obsessive-compulsive disorder. Int Clin Psychopharmacol 1997; 12:309-316Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

18. Spitzer RL, Williams JBW, Gibbon M, First MB: Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-III-R—Patient Version 1.0 (SCID-P). Washington, DC, American Psychiatric Press, 1990Google Scholar

19. Goodman WK, Price LH, Rasmussen SA, Mazure C, Fleischmann RL, Hill CL, Heninger GR, Charney DS: The Yale-Brown Obsessive Compulsive Scale, I: development, use, and reliability. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1989; 46:1006-1011Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

20. Goodman WK, Price LH, Rasmussen SA, Mazure C, Delgado P, Heninger GR, Charney DS: The Yale-Brown Obsessive Compulsive Scale, II: validity. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1989; 46:1012-1016Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

21. Murphy DL, Pickar D, Alterman IS: Methods for the quantitative assessment of depressive and manic behavior, in The Behavior of Psychiatric Patients. Edited by Burdock EL, Sudilovsky A, Gershon S. New York, Marcel Dekker, 1982, pp 355-392Google Scholar

22. Hamilton M: Development of a rating scale for primary depressive illness. Br J Soc Clin Psychol 1967; 6:278-296Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

23. Guy W (ed): ECDEU Assessment Manual for Psychopharmacology: Publication ADM 76-338. Washington, DC, US Department of Health, Education, and Welfare, 1976, pp 218-222Google Scholar

24. Endicott J, Nee J, Harrison W, Blumenthal R: Quality of Life Enjoyment and Satisfaction Questionnaire: a new measure. Psychopharmacol Bull 1993; 29:321-326Medline, Google Scholar

25. Rasmussen SA, Eisen JL, Pato MT: Current issues in the pharmacologic management of obsessive-compulsive disorder. J Clin Psychiatry 1993; 54(suppl 6):4-9Google Scholar

26. Ravizza I, Barzega G, Bellino S, Borgetto F, Maina G: Drug treatment of obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD): long-term trial with clomipramine and selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs). Psychopharmacol Bull 1996; 32:167-173Medline, Google Scholar