Mothers’ Functioning and Children’s Symptoms 5 Years After a SCUD Missile Attack

Abstract

OBJECTIVE: The authors assessed the long-term consequences of the SCUD missile attack in Israel on children as a function of their mothers’ psychological functioning, family cohesion, and the event itself. METHOD: Five years after the Gulf War, the authors assessed the internalizing, externalizing, stress, and posttraumatic symptoms of 81 children aged 8–10 years whose homes were damaged in the SCUD missile attack, as well as general and posttraumatic symptoms, defensive style, and object relations in their mothers. RESULTS: There was a significant decrease in severity in most symptom domains and an increase in avoidant symptoms in the children. Greater severity of symptoms was associated with being displaced, living in a family with inadequate cohesion, and having a mother with poor psychological functioning. The association between the symptoms of children and mothers was stronger among the younger children. Posttraumatic symptoms increased in one-third of the children and decreased in one-third over the last 30 months of the study. Severe posttraumatic symptoms were reported in 8% of the children. CONCLUSIONS: Despite a continuous decrease in symptom severity, risk factors identified shortly after the Gulf War continued to exert their influence on children 5 years after the traumatic exposure.

Considerable knowledge has accumulated during the last decade concerning children’s responses to disasters (1–4). Mental health professionals are aware that children, even preschoolers (5), may display specific posttraumatic symptoms, although they are somewhat different from those reported by adults (6). Young age (7), high degree of exposure (8), poor parental functioning (9, 10), and loss of family member (11) are some of the risk factors that predict poorer psychological functioning. Posttraumatic symptoms tend to decrease with time (12), although they may have a delayed onset (13).

The long-term consequences of traumatic events may serve as a suitable research paradigm for the growing field of developmental psychopathology (14). The present is our third investigation of a group of preschool children whose homes were damaged by SCUD missiles during the 1991 Gulf War. Some of them were displaced as a result. Our earlier studies were conducted 6 (15) and 30 months (16) after the conflict, and the present one after 5 years. This longitudinal approach with very young children, seldom reported in the literature (16), allowed us a unique perspective on the natural course of psychopathological responses in displaced and residentially stable children. Specifically, we made five major observations.

1. Stress symptoms decreased over time in residentially stable children, whereas increased posttraumatic responses persisted in displaced children.

2. The high correlation between the reactions of mothers and their very young children disappeared for older children.

3. Adequate family cohesion was very important for the well-being of the child.

4. Children displayed reasonably adaptive behavior despite the presence of psychological symptoms.

5. The mother’s capacity to control mental images had a direct moderating effect on her symptoms and an indirect effect on her child’s symptoms. At 30 months after the war, the symptoms of the displaced mothers remained high and predicted a significant amount of the children’s symptom levels.

The present study took a closer look at the role of the mothers’ psychological functioning 5 years after the war. We sought to answer two main questions: 1) what was the natural course of the general (internalizing, externalizing, and stress) and specific (intrusion, avoidance or numbing, and arousal) posttraumatic symptoms of displaced and residentially stable children? and 2) how did the mothers’ symptoms, maturity of defenses, object relations, and cognitive capacity to control mental images, as well as family functioning, affect the long-term adaptation of their children? On the basis of previous findings, we hypothesized that both general and specific posttraumatic symptoms would decrease over time and that the children’s symptoms were associated with poorer psychological functioning in their mothers and families.

Method

Subjects and Procedure

We requested the 107 families in the longitudinal cohort who were directly exposed to SCUD missile attacks 5 years earlier, during the Gulf War, to participate in a new interview session. A total of 81 families agreed to do so, 10 refused, and 16 could not be located. Multivariate comparisons between participating and nonparticipating families showed no significant differences in the previous symptoms of the children (internalizing, externalizing, stress, and posttraumatic stress disorder) (F=1.72, df=4, 101, p>0.05) or their mothers (intrusion, avoidance, and total SCL-90-R score) (F=1.24, df=3, 104, p>0.05).

All the families lived in the same neighborhood and had a low socioeconomic level. Forty families were displaced for a period of up to 6 months owing to the considerable damage inflicted on their homes by missiles, and 41 families remained residentially stable. At the first assessment, 30 children were aged 8 years, 29 were aged 9 years, and 22 were aged 10 years (10, 15). There were 24 boys and 57 girls. Experienced assistant researchers interviewed the children (for 1 hour) and the mothers (for 2 hours) individually in their homes. Written informed consent was obtained for all subjects after they received a complete description of the study.

Child Measures

The Child Behavior Checklist (17) covers two symptom domains, internalizing and externalizing. The Preschool Children’s Assessment of Stress Scale (unpublished, Mayes and Cohen, Yale Child Study Center, New Haven, Conn.) assesses stress reactions (fear, anxiety, or sleep problems) after a traumatic event (Cronbach’s alpha=0.89). Scales from these two instruments went through factor analysis previously (15), and three domains of symptoms were defined: internalizing (poor communication, depression, and somatic complaints), externalizing (aggression, delinquency, or hyperactivity), and stress (separation and sleep problems, mood changes, fears, and tension). The Child Posttraumatic Stress Reaction Index (8) is a 20-item, semistructured interview that covers the specific posttraumatic symptom domains of intrusion, avoidance or numbing, and arousal.

Maternal Measures

The Bell Object Relations Inventory (18) assesses four domains of object relations: alienation, egocentricity, insecure attachment, and social incompetence. The Defense Style Questionnaire (19) provides information on three defense styles: immature, neurotic, and mature. The SCL-90-R (20) measures general symptom profiles with the Global Severity Index. The Impact of Event Scale (21) measures intrusive and avoidant symptoms. Richardson’s revision (22) of the Gordon Test of Visual Imagery Control, a 12-item scale, measures the capacity to manipulate the mental image of “a car” (i.e., change its color, position, or movement). Image control has been found to correlate with the mature development of personality characteristics (23), intelligence (24), creativity (25), cognitive performance (26), and the affective regulation of psychophysiological responses after traumatic events (27).

At the 30-month assessment, the mothers also completed the Family Adaptability and Cohesion Evaluation Scales (28). This instrument assesses the capacity of the family to change its power structure, roles, and norms as a result of external pressures (adaptability) and the affective bonds between family members (cohesion). In the Family Adaptability and Cohesion Evaluation Scales, extreme scores reflect worse family functioning.

Results

On the basis of their level of symptoms (SCL-90-R score), object relations (score on Bell Object Relations Inventory), and defense style (score on Defense Style Questionnaire’s immature style), we divided the mothers into three categories of psychological functioning (N=27 in each). Mothers with poor functioning had a score above the median on the SCL-90-R and the Defense Style Questionnaire’s immature style and a score below the median on the Bell Object Relations Inventory. Mothers with moderate functioning had a score above the median on one or two of these measures and a score below the median on the other(s). Mothers with good functioning had a score below the median on the SCL-90-R and the Defense Style Questionnaire’s immature style and a score above the median on the Bell Object Relations Inventory. The intercorrelations between these scores were as follows (N=81): SCL-90-R and Bell Object Relations Inventory: r=–0.53; SCL-90-R and Defense Style Questionnaire: r=0.49; Bell Object Relations Inventory and Defense Style Questionnaire: r=–0.75; all p<0.001.

Children’s Symptoms

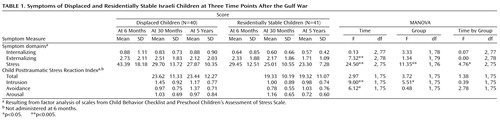

Table 1 summarizes the symptom scores of the displaced and residentially stable groups of children at three time points: 6 months, 30 months, and 5 years after the missile attack. Multivariate analysis of variance (MANOVA) with repeated measures (group by mother’s functioning by time) revealed that irrespective of the mother’s functioning (good, moderate, or poor; p>0.05 for all interactions), there was an overall significant decrease in the child’sexternalizing symptoms (F=7.62, df=2, 74, p<0.001) and stress (F=20.60, df=2, 71, p<0.0001) but not in internalizing symptoms (p>0.05). The decrease in the externalizing of symptoms from 30 months to the present assessment was significant (F=7.24, df=1, 78, p<0.01), but the decrease in stress symptoms was marginal (F=3.47, df=1, 77, p=0.07). Also a group-by-time interaction revealed that the decrease in stress symptoms was more remarkable in displaced children (F=3.33, df=2, 71, p<0.05).

With regard to the Child Posttraumatic Stress Reaction Index, analyses showed a significant decrease in arousal symptoms (F=4.07, df=1, 71, p<0.05), no significant changes in intrusive symptoms (p>0.05), and a significant increase in avoidance symptoms (F=7.89, df=1, 71, p<0.007). These effects were independent of the child’s group and the mother’s category of functioning (p>0.05 for all interactions).

Symptom Severity: Children

A group-by-sex-by-age MANOVA showed that at the last assessment, symptom scores were similar for boys and girls (F=0.48, df=7, 68, p>0.05), as well as for 8-, 9-, and 10-year-olds (F=0.46, df=14, 136, p>0.05). Therefore, age and sex were not considered in the remaining analyses. Displaced children had marginally higher symptom scores than residentially stable children (F=1.96, df=7, 68, p<0.08). For univariate analyses, differences were significant for the internalizing (F=3.95, df=1, 79, p<0.05), stress (F=5.36, df=1, 79, p<0.05), and avoidance (F=4.19, df=1, 75, p<0.05) domains.

Symptom Severity: Mothers

Displaced mothers reported significantly more symptoms than residentially stable mothers (MANOVA, F=8.61, df=3, 77, p<0.001). This was true for scores on the SCL-90-R (mean=152.7, SD=64.9, and mean=126.2, SD=45.0, respectively) (F=4.63, df=1, 79, p<0.05), Impact of Event Scale intrusive symptoms (mean=17.4, SD=7.2, and mean=11.1, SD=4.6) (F=22.01, df=1, 79, p<0.001), and Impact of Event Scale avoidance symptoms (mean=6.5, SD=4.8, and mean=14.6, SD=3.6) (F=4.25, df=1, 79, p<0.05).

Children and Mothers

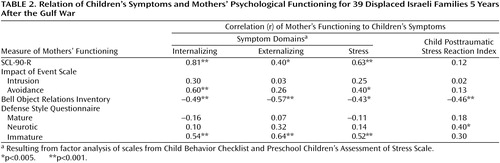

Table 2 presents the correlations between the symptom domains of the children and the psychological functioning variables of the mothers in displaced families. Increased symptoms in children were associated with poorer object relations, more immature defenses, and increased psychological symptoms in the mothers. A similar pattern, although with smaller coefficients and marginal statistical significance, appeared in residentially stable families.

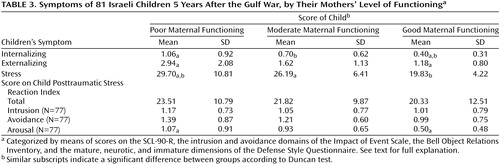

MANOVAs were performed to examine differences in symptoms among children of mothers from the three maternal function groups 5 years after the war (Table 3). For general symptoms (internalizing, externalizing, and stress), significant differences were noted on multivariate (F=4.91, df=6, 154, p<0.0001) and univariate (all p<0.005) analyses. Duncan’s post hoc tests revealed that children of mothers with poor functioning were characterized by greater symptom levels (in all three domains) than children of mothers with good functioning and that children of mothers with moderate functioning showed more internalizing symptoms than children of mothers with good functioning and fewer stress symptoms than children of mothers with poor functioning.

In the Child Posttraumatic Stress Reaction Index domains, multivariate analysis revealed no significant differences (F=1.09, df=8, 144, p>0.05), but univariate analysis reached significance for the arousal domain (F=4.16, df=2, 74, p<0.02). According to Duncan’s post hoc tests, children of mothers with good functioning reported fewer arousal symptoms than children with mothers with moderate and poor functioning.

Posttraumatic Stress

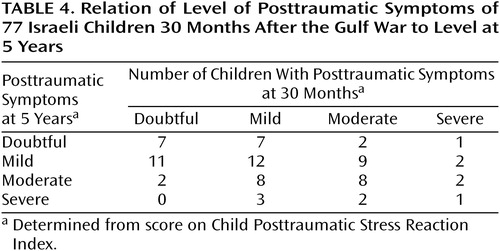

On the basis of the guidelines proposed by Pynoos et al. (29), children were classified as suffering from doubtful, mild, moderate, or severe posttraumatic symptoms 30 months and 5 years after the war. (No child met the criteria for the very severe category.)

Table 4 shows that 28 out of 77 children (36%) were classified in the same category at the two time points, whereas 26 children (34%) “advanced” one (N=21, 27%) or two (N=5, 6%) categories, and 23 children (30%) “receded” one (N=18, 23%) or two (N=5, 6%) categories.

Analysis of the “mobility” of the children across symptom categories by the functioning of the mothers yielded the following findings:

1. All children who were classified as having doubtful posttraumatic symptoms at 30 months and had mothers with poor functioning (N=4) showed a deterioration in symptoms and had advanced one or two categories at 5 years.

2. All children classified as having mild posttraumatic symptoms at 30 months and severe symptoms at 5 years (N=3) had mothers with poor functioning.

3. The two children who were characterized as having severe posttraumatic symptoms at 30 months and had mothers with good functioning had receded two or three categories at 5 years.

4. No child classified as having severe posttraumatic symptoms at 5 years had a mother with good functioning.

Family Functioning

In displaced families, Pearson’s correlations between family functioning at 30 months and the child’s symptoms 5 years after the war yielded an association between adequate cohesion and fewer symptoms of externalizing (r=0.59, df=79, p<0.001), internalizing (r=0.65, df=79, p<0.001), and stress (r=0.64, df=79, p<0.001). Also, adequate adaptability was associated with fewer internalizing (r=0.40, df=79, p<0.01) and stress (r=0.35, df=79, p<0.02) symptoms. In residentially stable families, there was no association between family functioning and the child’s symptoms (all p>0.05).

Children’s Ages

Pearson’s correlations tested how the children’s symptoms by age group related to the mothers’ symptoms (per SCL-90-R scores) and object relations 5 years after the war. The highest correlations were found for the youngest group (median=0.60, range=0.32–0.76), whereas most of the lowest correlations appeared in the oldest group (median=0.24, range=0.06–0.64).

Integrative Analyses

Finally, hierarchical regression analyses were performed with the children’s symptom domains as the dependent variables. The children’s age and sex made no significant contribution in the analyses. Inadequate family cohesion and the mother’s symptoms contributed to the explained variance of internalizing (F=36.61, df=2, 71, p<0.0001, R=0.71), externalizing (F=19.34, df=2, 71, p<0.0001, R=0.59), and stress (F=29.51, df=3, 70, p<0.0001, R=0.75) symptoms of the child. The mother’s capacity to control mental images (per score on Gordon Test of Visual Imagery Control) also contributed significantly tothe statistical prediction of stress symptoms, and it was the only predictor of the child’s specific posttraumatic symptoms (F=4.40, df=1, 67, p<0.05, R=0.25). Family’s inadequate cohesion, mother’s maturity of defenses, and length of the evacuation period after the missile attack explained about 60% of the variance in the mother’s symptoms (F=24.20, df=4, 67, p<0.0001, R=0.77).

Discussion

This 5-year follow-up is the third report on the natural course of symptoms of preschool children and their mothers exposed to a missile attack. It focused on the symptoms of the children and the mothers and the critical role of the mother’s psychological functioning and the adequacy of family cohesion.

Children’s Symptoms

Five years after the traumatic event, the children’s symptom profiles, both general (externalizing and stress), as well as specific posttraumatic symptoms (arousal), showed a significant decrease, regardless of gender or age. At the same time, however, there was a significant increase in the symptoms of avoidance. This may reflect the construction of long-term coping mechanisms to contain the distress generated by reexperiencing the traumatic event (30).

The present study replicated our original finding that displaced children show greater symptoms than residentially stable ones (see, also, reference 31). Here, the specific symptom domains involved were internalizing, stress, and avoidance but not externalizing, intrusion, and arousal. We speculate that in children, the long-term struggle with traumatic displacement is expressed in implosive symptoms (e.g., internalizing and avoidance) rather than in the more externally oriented explosive symptoms (e.g., externalizing, intrusion, and arousal). By contrast, the displaced mothers reported significantly more general—as well as posttraumatic—symptoms than the residentially stable mothers.

Children and Mothers

The association between increased symptoms in the child and poor psychological functioning in the mother was clear and robust. It should be stressed that the mothers’ psychological profile was assessed by means of three intercorrelated domains: competence to relate securely (object relations), skill in coping with internal and external stress (defensive style), and behavioral expressions of psychological dysfunction (symptoms). We observed that mothers with the poorest functioning had children with the most symptoms, whereas those with the best functioning had children with the least symptoms. Furthermore, the mothers’ psychological functioning seemed to have more of an effect on the “mobility” of the children across posttraumatic severity categories from the 30-month to the 5-year assessment than on the amount of posttraumatic symptoms per se. It appears that good functioning in the mothers helped the children “recede” from the severe categories, whereas their poor functioning resulted in their children “advancing” to the severe categories.

A total of 8% (6 out of 77) of the children reported having severe posttraumatic symptoms 30 months and 5 years after the war. However, half the children classified after 5 years as having severe symptoms had mild symptoms at the previous assessment. About one-third of the children in our study group showed the same severity of symptoms at both assessments (e.g., mild to mild), one-third showed a decrease in symptom severity (e.g., moderate to mild), and one-third showed an increase in severity (e.g., moderate to severe). Overall, the severity category of about two-thirds of the children was unstable. These data indicate that children might develop severe posttraumatic symptoms during the 5-year period after exposure to a traumatic event, even if symptoms were of moderate severity at a previous assessment (see, also, reference 13). In our children, this development was partly explained by poor psychological functioning in the mother.

Child’s Age

Although the symptoms of the children in our group were not associated with age, the correlations between the symptoms of the mothers and the children were different for the 8-, 9-, and 10-year-olds; there were significantly higher correlations in the group with the youngest members (who were 3 years old during the war). This finding is in line with our assessments at 6 and 30 months (10, 15), and its long-term and entrenched effect strengthens our suggestion that the potential impact of traumatic events on very young children is twofold—direct and indirect—through their effect on the caretaker. Furthermore, our longitudinal study supports the notion of a traumatic impact on the parent-child dyad, which, in younger children, is integral to the processing of the adverse experience (32).

Family Functioning

Family functioning at 30 months exerted a long-term effect on the children’s symptoms. This was true mainly for the displaced children, who experienced multiple traumas: the missile attacks, the destruction of their homes, and the physical displacement. (We could not differentiate among these traumas because all the displaced families lost their homes in the missile attacks. For the specific impact of the length of the evacuation, see the following.) Of the two family domains we assessed, family cohesion exerted the more powerful influence. Specifically, the combination of family displacement and a disengaged or enmeshed family style apparently induces a significant amount of stress in children, which not only jeopardizes their capacity to recover from the initial trauma but may also result in an increase in symptoms. Conversely, a displaced family characterized by adequate cohesion (not too loose or too tight) appears to provide a favorable environment for the child to work through the initial impact of the trauma and the consequent stressful reaction. In the residentially stable families, there was no association between family functioning and the children’s symptoms. We conclude that only under the stressful condition of displacement leading to increased symptoms is family functioning correlated with general symptoms of distress 5 years after the traumatic event.

Integrative Analyses

Our integrative analyses showed how the long-term effect of trauma in children is maintained by the combination of variables from different sources: symptoms, defensive style, and capacity to control mental imagery in the mothers, cohesion in the family, and length of the evacuation period.

Different variables predicted different aspects of the children’s symptoms. Internalizing and externalizing symptoms were directly predicted by the mothers’ general symptoms (SCL-90-R score) and by their family’s cohesion. The prediction of stress symptoms included also the mothers’ capacity to control mental images, which was the only predictor of the specific posttraumatic symptoms. Moreover, about 60% of the symptoms of the mothers were explained by their defensive style (more immature and less mature defenses) and (poor) capacity to control mental imagery, taken with the (inadequate) cohesion of the family and the (longer) period of evacuation of the family.

The issue of evacuation and displacement deserves special attention. The displacement of traumatized families and their temporary relocation may lead to social disintegration, with deleterious effects on family functioning (e.g., loss of daily family routine, loss of jobs, and attrition from school). Dysfunctional families serve as poor holding environments for their members, particularly for very young children, who still depend on parental support. In the absence of communal reactivation, the longer the evacuation period, the worse the effects on families and children.

In our previous report (at 30 months after the war), we found that the specific posttraumatic symptoms of the children were predicted by the mothers’ symptoms of avoidance. In turn, the latter were explained by the mothers’ general symptoms, capacity for image control, cohesion of the family, and length of evacuation. Five years after the war, the mothers’ specific symptoms lost their centrality, whereas their nonspecific symptoms predicted the children’s symptoms.

Our success in predicting the children’s posttraumatic symptoms was limited (only 6%). However, other variables related to the child (e.g., social support, IQ, and defense style) may have a significant effect in the long-term persistence of posttraumatic symptoms. As development proceeds, the child’s strengths and weaknesses begin to play a more central role in the dynamic interplay that involves the event and the responses of the immediate and distant environment, leading to long-term adaptation to the trauma (2). The increase in avoidance symptoms at this phase may reflect this interplay and demands further study.

Limitations

Although it was large enough to detect significant differences, our group size has decreased since the time of our previous report. A larger group would provide more statistical power for generalizing the results. This is especially true when we consider that the posttraumatic symptoms in our group were moderate. Second, we lack information on the fathers. These data could help us understand the symptomatic changes in some children over time (e.g., increase in avoidance symptoms). Third, we lack information on the coping behavior and intelligence level of the children. As development proceeds, these domains may take a more significant part in the process culminating in symptom expression.

Clinical Implications

Mental health professionals have little control over the occurrence of disasters. However, we have much to do to diminish their psychological consequences. Our data may be important for clinicians designing therapeutic interventions after disasters, as well as for authorities responsible for displaced populations. On the clinical level, therapeutic interventions involving traumatized children should integrate modules focusing on the family, allowing it to reach an adequate degree of cohesion in which individuals have enough personal space in which to retreat and also allowing the family members to feel supportive of each other. Furthermore, symptomatic mothers, especially of younger children, should be identified and helped, because their short-term and long-term functioning is a powerful risk factor for the children’s well-being. Finally, authorities should consider the psychological effects of displacement and shorten its duration as much as possible.

|

|

|

|

Received Feb. 24, 2000; revision received Oct. 31, 2000; accepted Dec. 20, 2000. From the Tel Aviv–Community Mental Health Center, Sackler School of Medicine, Tel Aviv University, Tel Aviv; and the Yale Child Study Center, New Haven, Conn. Address reprint requests to Dr. Laor, Tel Aviv–Community Mental Health Center, 9 Hatzvi St., Tel Aviv, Israel, 67197; [email protected] (e-mail).

1. Pfefferbaum B: Posttraumatic stress disorder in children: a review of the past 10 years. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 1997; 36:1503-1511Google Scholar

2. Pynoos RS, Steinberg AM, Wraith R: A developmental model of posttraumatic stress disorder in children and adolescents, in Developmental Psychopathology, vol 2. Edited by Cicchetti D, Cohen DJ. New York, John Wiley & Sons, 1995, pp 72-95Google Scholar

3. Vogel JM, Vernberg EM: Children’s psychological responses to disasters. J Clin Child Psychol 1993; 22:470-484Crossref, Google Scholar

4. Yule W, Williams RM: Post-traumatic stress reactions in children. J Trauma Stress 1990; 3:279-295Crossref, Google Scholar

5. Scheeringa MS, Zeanah CH, Drell MJ, Larrieu JA: Two approaches to the diagnosis of posttraumatic stress disorder in infancy and early childhood. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 1995; 34:191-200Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

6. Terr LC: Psychic trauma in children and adolescents. Psychiatr Clin North Am 1985; 8:815-835Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

7. Green BL, Korol M, Grace MC, Vary MG, Leonard AC, Gleser GC, Smitson-Cohen S: Children and disaster: age, gender, and parental effects on PTSD symptoms. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 1991; 30:945-951Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

8. Pynoos RS, Frederick C, Nader K, Arroyo W, Steinberg A, Eth S, Nunez F, Fairbanks L: Life threat and post-traumatic stress in school-age children. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1987; 44:1057-1063Google Scholar

9. Korol M, Green BL, Gleser GC: Children’s responses to a nuclear waste disaster: PTSD symptoms and outcome prediction. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 1999; 38:368-375Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

10. Laor N, Wolmer L, Mayes LC, Gershon A, Weizman R, Cohen DJ: Israeli preschoolers under Scuds: a 30-month follow-up. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 1997; 36:349-356Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

11. Pfefferbaum B, Nixon SJ, Tucker PM, Tivis RD, Moore VL, Gurwitch RH, Pynoos RS, Geis HK: Posttraumatic stress responses in bereaved children after the Oklahoma City bombing. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 1999; 38:1372-1379Google Scholar

12. Becker DF, Weine SM, Vojvoda D, McGlashan TH: Case series: PTSD symptoms in adolescent survivors of “ethnic cleansing”: results from a 1-year follow-up study. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 1999; 38:775-781Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

13. Sack WH, Him C, Dickason D: Twelve-year follow-up study of Khmer youths who suffered massive war trauma as children. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 1999; 38:1173-1179Google Scholar

14. Cicchetti D, Cohen DJ (eds): Developmental Psychopathology. New York, John Wiley & Sons, 1995Google Scholar

15. Laor N, Wolmer L, Mayes LC, Golomb A, Silverberg D, Weizman R, Cohen DJ: Israeli preschoolers under Scud missile attacks: a developmental perspective on risk-modifying factors. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1996; 53:416-423Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

16. Green BL, Grace MC, Vary MG, Kramer TL, Gleser GC, Leonard AC: Children of disaster in the second decade: a 17-year follow-up of Buffalo Creek survivors. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 1994; 33:71-79Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

17. Achenbach TM, Edelbrock C: Manual for the Child Behavior Checklist and Revised Child Behavior Profile. Burlington, University of Vermont, Department of Psychiatry, 1983Google Scholar

18. Bell M, Billington R, Becker B: A scale for assessment of object relations: reliability, validity, and factorial invariance. J Clin Psychol 1985; 42:733-741Crossref, Google Scholar

19. Andrews G, Singh M, Bond M: The Defense Style Questionnaire. J Nerv Ment Dis 1993; 181:246-256Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

20. Derogatis LR: SCL-90-R: Administration, Scoring, and Procedures Manual, I, for the Revised Version. Baltimore, Johns Hopkins University, Clinical Psychometrics Research Unit, 1977Google Scholar

21. Horowitz MJ, Wilner N, Alvarez W: Impact of Event Scale: a measure of subjective stress. Psychosom Med 1979; 41:209-218Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

22. Richardson A: Mental Imagery. London, Routledge & Kegan Paul, 1969Google Scholar

23. Kovach BE: Imagery, personality, and emotional response. J Ment Imagery 1988; 12:63-74Google Scholar

24. Tedford WH Jr, Penk ML: Intelligence and imagery in personality. J Pers Assess 1977; 41:405-413Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

25. Shaw GA, DeMers ST: The relationship of imagery to originality, flexibility, and fluency in creative thinking. J Ment Imagery 1986; 10:65-74Google Scholar

26. Lowrie T: The use of visual imagery as a problem-solving tool: classroom implementation. J Ment Imagery 1996; 20:127-140Google Scholar

27. Laor N, Wolmer L, Wiener Z, Reiss A, Muller U, Weizman R, Ron S: The function of image control in the psychophysiology of posttraumatic stress disorder. J Trauma Stress 1998; 11:679-696Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

28. Olson DH: Circumplex Model VII: validation studies and FACES III. Fam Process 1986; 25:337-351Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

29. Pynoos RS, Goenjian A, Tashjian M, Karakashian M, Manjikian R, Manoukian G, Steinberg AM, Fairbanks LA: Posttraumatic stress reactions in children after the 1988 Armenian earthquake. Br J Psychiatry 1993; 163:239-247Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

30. McFarlane AC: Avoidance and intrusion in posttraumatic stress disorder. J Nerv Ment Dis 1992; 180:439-445Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

31. Lonigan CJ, Shannon MP, Taylor CM, Finch AJ Jr, Sallee FR: Children exposed to disaster, II: risk factors for the development of post-traumatic symptomatology. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 1994; 33:94-105Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

32. Wolmer L, Laor N, Gershon A, Mayes L, Cohen DJ: The mother-child facing trauma: a developmental outlook. J Nerv Ment Dis 2000; 188:409-415Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar