A Psychiatric Epidemiological Study of Postpartum Chinese Women

Abstract

OBJECTIVE: Epidemiological studies in the 1980s have suggested that depression is rare in the Chinese population and there is no postpartum depression among Chinese women. However, subsequent small-scale studies of postpartum depression in China have yielded contradictory and inconsistent findings. Furthermore, after two decades of profound socioeconomic transformation, depression may no longer be rare in the contemporary population. The authors conducted a psychiatric epidemiological study among postpartum Chinese women using rigorous methodology and a representative sample. METHOD: A total of 959 consecutive women were recruited at the antenatal clinic of a university hospital in Hong Kong. At 3 months postpartum, the prevalence and incidence rates of depression were measured with a two-phase design. The participants were first stratified by means of the 12-item General Health Questionnaire. Subsequently, all high scorers and 10% of low scorers were assessed with the nonpatient version of the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-III-R. The 1-month and 3-month prevalence and incidence rates were estimated by using reverse weighting. RESULTS: The 1-month prevalence rates for major and minor depression were 5.5% and 4.7%, respectively. At 3 months, the corresponding prevalence rates were 6.1% and 5.1%. Together, 13.5% of the participants suffered from one or more forms of psychiatric disorder in the first 3 months postpartum. CONCLUSIONS: Postpartum depression is common among contemporary Chinese women. A universal postpartum depression-screening program would be useful for early detection. Our data suggest that depression may no longer be rare in the Chinese population.

Epidemiological studies of postpartum psychiatric morbidity in Western societies have generally reported that 10%–15% of recently delivered women are afflicted with nonpsychotic depression, commonly known as postpartum depression (1–4). Postpartum depression is a serious disorder because it causes long-lasting adverse effects on the emotional and cognitive development of the children of affected women (5–7). The juxtaposition of the joy of having a new baby with the distress brought about by a stigmatizing mental illness renders the experience particularly traumatic and difficult to cope with.

Few studies, however, have examined the occurrence of other psychiatric disorders, such as anxiety and adjustment disorders, in the postpartum period (8, 9). Even fewer have studied postpartum mental illness in Chinese and other non-Western populations (10–12). A commonly cited anthropological study (13) has suggested that postpartum depression is absent in China because of the enriched postpartum social network provided by the family. However, studies making use of self-report postpartum depression screening scales (14–20) have yielded widely varying prevalence rates for postpartum depression, ranging from 0% to 18% in various Chinese populations. Our small-scale study (21) estimated that 12% of recently delivered Hong Kong women suffer from major or minor depression. These divergent findings are partly due to the small and unrepresentative groups employed in many of these studies. In addition, all but the latter study did not use structured clinical interviews or operational criteria in establishing diagnoses. To clarify these contradictory findings, a large-scale study making use of rigorous methodology and representative sampling was clearly necessary.

The epidemiological investigation of postpartum depression among contemporary Chinese women had a second function that would interest a wider psychiatric audience: it would serve as a lens to update our understanding of depression in Chinese society. Population-based epidemiological studies in the 1980s suggested that depressive disorders are rare in the Chinese population. With the use of designs and instruments similar to those found in the Epidemiologic Catchment Area (ECA) study in the United States, studies in Hong Kong (22) and Taiwan (23) reported a 0.9%–2.4% lifetime prevalence of major depression among Chinese women. This contrasts with the lifetime prevalence of 8.7% (found in New Haven, Conn.), 4.9% (in Baltimore), and 8.1% (in St. Louis) in the ECA study (24).

However, these earlier findings of low rates of depression among Chinese women may no longer be applicable to contemporary Chinese society because of the momentous socioeconomic transformations occurring in the past decades. Since the 1960s, Hong Kong has been transformed from a fishing village-cum-entrepôt into an internationally acclaimed metropolis and financial hub, with a gross domestic product of $23,000 (U.S.) per capita. This rapid industrialization has brought about unprecedented changes in the family structure, gender roles, labor markets, sociomoral values, cultural identity, health, and housing of 6 million people (25). Even worse, many of these changes ruthlessly intensified in the post-1997 era when Hong Kong was struck by Asia’s economic downturn. In China, profound socioeconomic transformations have also occurred during the past two decades, taking a heavy toll on the social and mental health of the population (26). Although a population-based epidemiological study will be the ultimate approach to document these changes, a smaller scale epidemiological study within a well-defined context, such as during puerperium, would provide a quick and expedient glimpse of the situation. If we indeed were to confirm that 12% of contemporary Chinese women suffer from postpartum depression, it would support the notion that depressive illness is no longer a rare form of psychiatric morbidity in Chinese populations, and a new wave of population-based psychiatric epidemiological investigations would be in order.

Method

Sample

A total of 959 participants were recruited among women who were consecutively admitted to the antenatal booking clinic of the Prince of Wales Hospital. The Prince of Wales Hospital is a university-affiliated public facility that serves a population of 1 million people from diverse socioeconomic backgrounds. Pregnant women who desire to deliver in the public health services are required to visit this booking clinic. Women were excluded from the study only if they 1) were not of Chinese ethnicity, 2) did not have long-term residential rights, 3) were leaving Hong Kong within 12 months of delivery, or 4) did not supply written informed consent.

Assessment Protocol

After complete description of the study was given to the subjects, written informed consent was obtained. We recruited participants at their first antenatal assessment and subsequently reassessed them in their third trimester, immediately after delivery, and 3 months postpartum for depressive symptom profiles. The research protocol was approved by the hospital’s institutional review board.

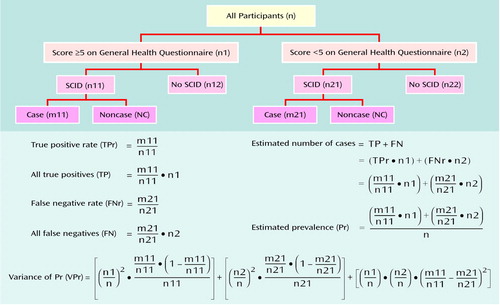

At baseline, research assistants collected sociodemographic, medical, obstetrical, and psychiatric data from the participants in a semistructured manner. At 3 months postpartum, the prevalence and incidence rates of postpartum psychiatric morbidity were measured by using a two-phase design (Figure 1). In the first phase, participants completed the 12-item General Health Questionnaire (27), a self-reported rating scale that is commonly used to screen for psychiatric morbidity. In the second phase, all participants with high scores on the General Health Questionnaire (5 or higher) were assessed by one of the authors (D.T.S.L.) by means of the nonpatient version of the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-III-R (SCID) (28). A total of 10% of the participants with low scores (4 or lower) on the General Health Questionnaire were randomly selected by one of us (D.T.S.L.) to receive the SCID interview to determine the rate of false negatives.

Our cutoff score on the Chinese General Health Questionnaire (29) in detecting postpartum depression among Hong Kong women was validated in a prior study (30). At the optimal cutoff score of 4.5, the sensitivity, specificity, and positive predictive value of the General Health Questionnaire in detecting postpartum depression are 0.88, 0.89, and 0.52. In the present study, the SCID was modified to make 3-month (instead of 1-month) diagnoses because the participants were assessed at 3 months postpartum.

Although the SCID is a semistructured interview, it allows the interviewer to use additional questions to inquire about idioms of distress that are specific to the local context. This ensures that the diagnostic interview is culturally informed. Traditional Chinese culture stipulates that women should adhere to a constellation of customs in the first month after childbirth. For instance, recent parturients should avoid going outside, being exposed to drafts, or coming into contact with cold water. It is believed that failure to comply with these ethnomedical restrictions causes “wind” to enter the body, leading to chronic poor health, headache, and rheumatism. Such cultural patterning of the puerperal period shapes the clinical presentation of postpartum depression. Hence, instead of reporting, “I am depressed,” Chinese women commonly express their emotional distress using somatic complaints or physical idioms of distress, such as headache, head numbness, “wind inside the head,” diffuse joint pains, or “wind illness” (13, 31).

Failure to recognize these local idioms may therefore lead to underdetection of postpartum depression. Local distress idioms are also a useful means by which to overcome initial denial in face-to-face interviews. Because mental illness is heavily stigmatized in Chinese societies, when a respondent is directly questioned by an unfamiliar interviewer, she may initially deny her depressive symptoms. The denial and resistance, however, can often be overcome by discussion of local distress idioms, which are a culturally legitimized means by which to communicate private emotional experiences.

Statistical Analysis

The sociodemographic and psychosocial characteristics of the participants were summarized by using descriptive statistics. The characteristics of the participants who were not included in the 3-month assessment were compared with those who were assessed by using the chi-square test for categorical data (e.g., marital status) and the t test for ordinal data (e.g., age). The hypotheses tests were based on raw, unweighted data. Because nearly 20 hypotheses were tested in checking for potential biases introduced by the 3-month attrition, a conservative threshold for significance (p<0.01) was used instead of the conventional p<0.05. The 1-month and 3-month prevalence and incidence rates were estimated by using reverse weighting, as described by Dunn et al. (32). The formulas for the weight prevalences and their variances are summarized in Figure 1.

Results

Characteristics of the Participants

A total of 1,600 women were approached for recruitment; 959 (60%) of the women participated. A total of 781 (81%) of the participants were included in the 3-month postpartum assessment; their sociodemographic characteristics are summarized in Table 1. Among the 178 (19%) of the women who left the study, 99 (10%) of 959 withdrew their consent, 56 (6%) could not be contacted, and 23 (2%) suffered a miscarriage. The participants who were not included in the 3-month follow-up were not different from those who remained in the study in terms of sociodemographic characteristics, past depressive episodes, or deliberate self-harm (Table 1). Baseline levels of depression, quality of the marital relationship, and social supports were not significantly different between the two cohorts. However, those who were not included in the 3-month assessment were more likely to be of later gestation at recruitment.

Prevalence and Incidence Rates

Among the participants who were included in the 3-month assessment, 96 (12%) scored above the General Health Questionnaire cutoff. A total of 92 participants who scored higher than 4 on the General Health Questionnaire were interviewed by means of the SCID. The results of one of the SCID diagnostic interviews were classified as invalid because the participant’s attitude was defensive. Four participants who scored higher than 4 on the General Health Questionnaire were not interviewed for practical reasons. A total of 685 (88%) of the participants scored lower than 5 on the General Health Questionnaire, of whom 62 (9%) were randomly chosen to respond to the SCID.

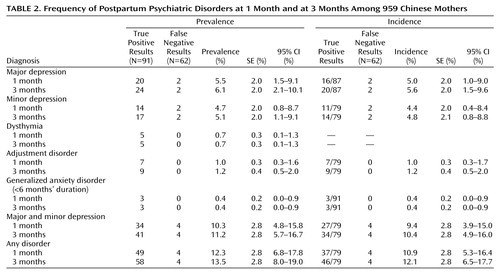

Table 2 shows the frequencies of postpartum psychiatric disorders at 1 month and 3 months. One participant was diagnosed with double depression at 3 months postpartum. The incidence rates of adjustment disorders and generalized anxiety disorder were equal to their prevalence rates because no cases began before delivery.

Discussion

Our study shows that postpartum depression is common among contemporary Hong Kong women. Approximately 6% of our participants suffered major depression and 5% suffered minor depression in the first month postpartum. These figures are similar to our earlier findings (21). A meta-analysis of 59 studies (including 12,810 women) by O’Hara and Swain (34) reported a 7% prevalence rate of DSM major depression and an 11% prevalence rate of Research Diagnostic Criteria major and minor depression. Our findings, hence, do not lend support to the notion that Chinese women are immune or protected from postpartum depression. On the contrary, the data suggest that the rate of depression among Chinese women is not different from the rates found among women of childbearing age in Western societies, whether postpartum or not. Obstetricians and psychiatrists should be aware that one in 10 contemporary Hong Kong women in the postpartum period suffers from depressive disorders.

The present study shows that this depressive episode was the first encounter with mental illness in 93% (104 out of 112) of our depressed participants. As such, the women and their families may have had little knowledge of depression and may have misconstrued the mental illness as maladjustment to sleep deprivation, childbearing, and parenthood. Fear of stigmatization and psychological denial may further delay these women from seeking proper treatment. For these reasons, and the fact that the onset of postpartum depression is synchronized to a well-defined time point, a universal screening program would be tremendously useful to diagnose depression in postpartum women.

Nowadays, postpartum depression is so powerful and dominant as a diagnostic category that it overshadows research on other postpartum psychiatric disorders, such as anxiety or adjustment disorders. Although the present study confirms that depression is indeed the predominant form of psychiatric morbidity in the postpartum period, it also suggests that generalized anxiety disorders, dysthymia, and adjustment disorders are also present in the postpartum period. Inasmuch as these disorders are rather rare (i.e., with 3-month prevalences of about 1%), a large-scale study is necessary to collect adequate data for meaningful analysis of the specific characteristics, etiologies, treatment responses, and long-term outcomes of these disorders. Before information from such studies is available, clinicians should remain vigilant for these relatively uncommon forms of morbidity in postpartum women.

Several limitations of this study deserve special discussion. First, 19% of the participants were not included in the 3-month assessment. Although the participants who were not included were not different from those who responded to the diagnostic interview in terms of sociodemographic or psychiatric characteristics, they were more likely to be of later gestation at recruitment. Second, about 40% of the eligible women declined to participate in the study, and only limited sociodemographic data were available from these nonparticipants to evaluate the potential bias they may have introduced. Third, although the average rate of miscarriage is 10%–15% of all pregnancies in the general population, only 2% of our participants had a miscarriage during the study. Instead of reflecting a sampling bias, this was probably due to the fact that majority of the participants joined the study after their first trimester, when most miscarriages occur.

Previous studies have shown that a past history of depression, including a past postpartum episode, increases the risk of postpartum depression. Our data, however, showed that previous depressive episodes were present in only approximately 7% of the cases of postpartum depression. We speculate that this low rate is related to the low fertility rate of Hong Kong women. At present, the average number of children per Hong Kong family is close to one. Because most women, including our participants, have only one child in their lifetimes, they do not have any past postpartum depressive episodes. This may partly explain why a past history of depression is rare even among the participants who had postpartum depression. Finally, because the present study was conducted among Hong Kong women, further replications in other regions of China are necessary.

The findings of the present study should be read in the wider context of psychiatric epidemiology among the Chinese. Our data suggest that the lifetime prevalence of major depression in contemporary Hong Kong women of reproductive age is at least 6%, several-fold higher than the age- and gender-matched lifetime prevalence (0.9%–2.5%) reported by the aforementioned population-based epidemiological studies (22, 23). In the present study, precautions were taken to ensure sample representativeness. The validity of the findings is also enhanced by the use of a standardized and internationally recognized research design, diagnostic instrument, and set of classificatory criteria. Hence, the higher rate of depression in contemporary Hong Kong women requires other explanations.

First, it is possible that the prevalence rates of depression were underestimated in previous epidemiological surveys because of cross-cultural discrepancies in diagnostic concepts and practices. Neurasthenia, a nosological concept that has largely disappeared in Western psychiatry, is still commonly employed by Chinese psychiatrists. Kleinman (35) has shown that the Chinese concept of neurasthenia overlaps substantially with that of DSM nonpsychotic depression. However, in mainland Chinese epidemiological surveys, neurasthenia (prevalence of 8%–14%) has not been counted toward the overall rates of depression (36, 37). In the epidemiological surveys conducted in Hong Kong and Taiwan, the research instruments were not modified to enable diagnosis of neurasthenia (22, 23). All of these practices may contribute to an underestimation of the overall prevalence rate of depression in Chinese populations.

Alternatively, there may be a genuine increase in the prevalence rate of depression in Chinese societies. Traditional values and sociocultural factors, such as family cohesiveness, a low divorce rate, and parental substitutes, have often been cited to explain the low rates of all depression in Chinese studies from the 1980s (22, 23). However, these putative protective factors may no longer be relevant, as we have seen divorce, family violence, job insecurity, child and sexual abuse, juvenile pregnancy, deterioration in network solidarity, and alcohol and drug addiction invade the nuclear family in recent times (26). China now has the highest suicide rates in the world among elderly people and young women (38). The past two decades of epidemiological studies in China have also shown that the prevalence of affective disorders has been consistently rising (39). As Chinese societies are steadily Westernized and urbanized in the process of profound socioeconomic transformation, it is possible, and indeed commonsensical, that the observed pattern of psychiatric morbidity in Chinese communities will be moving closer to those seen in the West. Although our findings and interpretations should be treated as preliminary, a new wave of psychiatric epidemiological studies of Chinese populations is certainly in order.

|

|

Presented in part at the biannual scientific meeting of the Australian Marce Society, Melbourne, Australia, Sept. 17–18, 1999. Received Dec. 10, 1999; revision received June 9, 2000; accepted Sept. 21, 2000. From the Department of Social Medicine, Harvard Medical School, Boston; and the Department of Psychiatry and the Department of Obstetrics and Gynaecology, The Chinese University of Hong Kong. Address reprint requests to Dr. Lee, Department of Psychiatry, The Chinese University of Hong Kong, Sha Tin, N.T., Hong Kong; [email protected] (e-mail). Supported by grant 621019 from the Health Services Research Fund of Hong Kong. The authors thank A. Becker, S. Eguchi, and Y.K. Wing for their comments.

Figure 1. Two-Phase Study Design and Formulas for Estimating Prevalences and Variances of Postpartum Psychiatric Disorders Among 959 Chinese Mothers

1. O’Hara MW, Schlechte JA, Lewis DA, Varner MW: Controlled prospective study of postpartum mood disorders: psychological, environmental, and hormonal variables. J Abnorm Psychol 1991; 100:63–73Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

2. Georgiopoulos AM, Bryan TL, Houston MS, Yawn BP, Rummans TA, Evans MP, McKeon KK, Therneau TM: Screening for postpartum depression in Olmsted County, Minnesota: a population-based study using the Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale (abstract). Psychosomatics 1999; 40:135Crossref, Google Scholar

3. Nonacs R, Cohen LS: Postpartum mood disorders: diagnosis and treatment guidelines. J Clin Psychiatry 1998; 59:34–40Medline, Google Scholar

4. Stowe ZN, Nemeroff CB: Women at risk for postpartum-onset major depression. Am J Obstet Gynecol 1995; 173:639–645Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

5. Murray L, Cooper PJ: Postpartum depression and child development. Psychol Med 1997; 27:253–260Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

6. Hay DF, Kumar R: Interpreting the effects of mothers’ postnatal depression on children’s intelligence: a critique and re-analysis. Child Psychiatry Hum Dev 1995; 25:165–181Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

7. Weinberg MK, Tronick EZ: The impact of maternal psychiatric illness on infant development. J Clin Psychiatry 1998; 59(suppl 2):53–61Google Scholar

8. Stuart S, Couser G, Schilder K, O’Hara MW, Gorman L: Postpartum anxiety and depression: onset and comorbidity in a community sample. J Nerv Ment Dis 1998; 186:420–424Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

9. Ballard CG, Davis R, Handy S, Mohan RN: Postpartum anxiety in mothers and fathers. Eur J Psychiatry 1993; 7:117–121Google Scholar

10. Becker AE, Cohen LS: A prospective study of postpartum mood disturbance in Fiji, in 1996 Annual Meeting New Research Program and Abstracts. Washington, DC, American Psychiatric Association, 1996, p 156Google Scholar

11. Okano T, Nomura J, Kumar R, Kaneko E, Tamaki R, Hanafusa I, Hayashi M, Matsuyama A: An epidemiological and clinical investigation of postpartum psychiatric illness in Japanese mothers. J Affect Disord 1998; 48:233–240Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

12. Yoshida K, Marks MN, Kibe N, Kumar R, Nakano H, Tashiro N: Postnatal depression in Japanese women who have given birth in England. J Affect Disord 1997; 43:69–77Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

13. Pillsbury BLK: “Doing the month”: confinement and convalescence of Chinese women after childbirth. Soc Sci Med 1978; 12:11–22Medline, Google Scholar

14. Kok LP, Chan PS, Ratnam SS: Postnatal depression in Singapore women. Singapore Med J 1994; 35:33–35Medline, Google Scholar

15. Zheng S, Huang T, Zou X: Evaluation of the Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale and analysis of the findings. J Clin Psychol Med Settings 1996; 6:236–237Google Scholar

16. Kit LK, Janet G, Jegasothy R: Incidence of postnatal depression in Malaysian women. J Obstet Gynaecol Res 1997; 23:85–89Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

17. Guo SF, Chen LK, Bao YC, Wang T: [Postpartum depression.] Chung Hua Fu Chan Ko Tsa Chih 1993; 28:532–533, 569 (Chinese)Google Scholar

18. Pen T, Wang L, Jin Y, Fan X: [The evaluation and application of the Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale.] Chinese Ment Health J 1994; 8:18–19, 4 (Chinese)Google Scholar

19. Cheng RCH, Lai SSL, Sin HFK: A study exploring the risk of postnatal depression and the help-seeking behaviour of postnatal women in Hong Kong. Hsiang Kang Hu Li Tsa Chih 1994; 68:12–17Google Scholar

20. Sheng SN: Clinical analysis of 15 cases with postnatal depression. J Clin Psychol Med Settings 1996; 6:358Google Scholar

21. Lee DTS, Yip SK, Chiu HFK, Leung TYS, Chan KPM, Chau IOL, Leung HCM, Chung TKH: Detecting postnatal depression in Chinese women: validation of the Chinese version of the Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale. Br J Psychiatry 1998; 172:433–437Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

22. Chen CN, Wong J, Lee N, Chan-Ho MW, Lau JTF, Fung M: The Shatin Community Mental Health Survey in Hong Kong. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1993; 50:125–133Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

23. Hwu HG, Yeh EK, Chang LY: Prevalence of psychiatric disorders in Taiwan defined by the Chinese Diagnostic Interview Schedule. Acta Psychiatr Scand 1989; 79:136–147Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

24. Robins LN, Helzer JE, Weissman MM, Orvaschel H, Gruenberg E, Burke JD Jr, Regier DA: Lifetime prevalence of specific psychiatric disorders in three sites. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1984; 41:949–958Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

25. Lee S: Fat, fatigue and the feminine: the changing cultural experience of women in Hong Kong. Cult Med Psychiatry 1999; 23:51–73Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

26. Kleinman A, Kleinman J: The transformation of everyday social experience: what a mental and social health perspective reveals about Chinese communities under global and local change. Cult Med Psychiatry 1999; 23:7–24Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

27. Goldberg DP: Manual of the General Health Questionnaire. Windsor, UK, National Foundation for Educational Research, 1978Google Scholar

28. Spitzer RL, Williams JBW, Gibbon M, First MB: The Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-III-R (SCID), I: history, rationale, and description. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1992; 49:624–629Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

29. Pan PC, Goldberg DP: A comparison of the validity of GHQ-12 and CHQ-12 in Chinese primary care patients in Manchester. Psychol Med 1990; 20:931–940Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

30. Lee DTS, Yip SK, Chiu HFK, Leung TYS, Chung TKH: Screening for postnatal depression: are specific instruments mandatory? J Affect Disord (in press)Google Scholar

31. Eisenbruch M: “Wind illness” or somatic depression? a case study in psychiatric anthropology. Br J Psychiatry 1983; 143:323–326Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

32. Dunn G, Pickles A, Tansella M, Vazquez-Barquero JL: Two-phase epidemiological surveys in psychiatric research. Br J Psychiatry 1999; 174:95–100Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

33. Office of Population and Surveys: Classification of Occupations. London, Her Majesty’s Stationery Office, 1970Google Scholar

34. O’Hara MW, Swain AM: Rates and risk of postpartum depression—a meta-analysis. Int Rev Psychiatry 1996; 8:37–54Crossref, Google Scholar

35. Kleinman A: Neurasthenia and depression: a study of somatization and culture in China. Cult Med Psychiatry 1982; 6:117–190Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

36. Cooper JE, Sartorius N: Results: the prevalence of mental disorders, in Mental Disorders in China. Edited by Cooper JE, Sartorius N. London, Gaskell, 1996, pp 44–73Google Scholar

37. Zhang W, Shen Y, Li S: Epidemiological investigation on mental disorders in seven areas of China. Chinese J Psychiatry 1998; 31:69–71Google Scholar

38. Phillips MR, Liu H, Zhang Y: Suicide and social change in China. Cult Med Psychiatry 1999; 23:25–50Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

39. Wang J, Wang D, Shen Y: Epidemiological survey on affective disorder in seven areas of China. Chinese J Psychiatry 1998; 5:75–77Google Scholar