Low Prevalence of Psychoses Among the Hutterites, an Isolated Religious Community

Abstract

OBJECTIVE: The authors estimated the prevalence of psychoses among the Hutterites in Manitoba, Canada, who lived in 102 communal farms or colonies. The study stemmed from an earlier epidemiological survey of North American Hutterite colonies (1950–1953), in which a low prevalence of psychoses was documented.METHOD: Psychiatrically ill individuals identified during the previous survey were rediagnosed with DSM-IV criteria. A current provincial health insurance claims database was queried anonymously for the period June 1992–May 1997, and the prevalence rate of disease among Hutterites, identified by distinctive surnames and unique postal addresses, was compared with the rate in the entire population of the province of Manitoba and in a comparison group of persons with Hutterite surnames but with addresses outside the Hutterite colonies.RESULTS: The annual prevalence of schizophrenia among the communal Hutterites, estimated from the database search by using ICD-9 criteria, was consistent with the prevalence found in the prior epidemiological survey (annual mean of 1.2/1,000 population, compared with 1.3/1,000 in the prior survey). The database search yielded a significantly lower prevalence for schizophrenia and other functional psychoses among communal Hutterites as well as among the comparison group, compared to the total Manitoba population. There was also lower prevalence for affective psychoses and adjustment reaction disorders among the communal Hutterites, compared to the total Manitoba population. Rates for neurotic disorders were elevated both among the communal Hutterites and the comparison group.CONCLUSIONS: The prevalence of specific psychoses was reduced among the Hutterites, although neurotic disorders were more prevalent. These findings suggest some specificity, although possible artifacts such as ascertainment bias must be considered. Further research is needed to examine genetic and environmental factors that may contribute to reduced prevalence of specific psychoses among the Hutterites.

Epidemiological surveys of unique communities are important, as significant variation can provide important insights into etiology. Complete ascertainment of psychiatrically ill Hutterites, who belong to an isolated North American religious community, was first achieved in 1950–1953 (1). All major psychiatric disorders were detected. It was observed that Hutterites readily sought treatment for psychiatric conditions. The reported lifetime rate of schizophrenia among Hutterites was lower (1.1/1,000 population or 2.1/1,000 persons aged 15 years or more) than contemporary estimates from other populations. All psychotic individuals identified in the original survey were recently rediagnosed using DSM-III-R criteria (2). The rates for schizophrenia and bipolar disorder were estimated at 0.9 and 0.6/1,000 population, respectively. Thus, the low rates originally observed in 1950–1953 are unlikely to be due to misclassification.

The Hutterites are an Anabaptist Christian sect that originated in the Tyrolean Alps in about 1528. They migrated eastward over the next two centuries in response to religious persecution (3). Their numbers grew to 1,265 in the Ukraine during the nineteenth century. They migrated en masse to the United States in 1874–1877. The majority homesteaded individual farms, but 443 individuals (101 couples) continued communal living practices. These individuals, along with three large families that joined the Hutterites between 1883 and 1892, and a few migrants, constitute the ancestors of the current communal Hutterites, referred to here as “Hutterites” (4). The current Hutterite population exceeds 40,000 (personal communication, T. Waldner, Forest River Hutterite Colony, North Dakota, 1999). Endogamy is the norm and has been documented since 1880. The overwhelming majority of the North American Hutterites are descendants of 89 founders, 43 females and 46 males (T.M. Fujiwara, K. Morgan, unpublished data, 1999).

The Hutterites are divided into three distinct kinship groups, named the Schmiedeleut, the Dariusleut, and the Lehrerleut. Currently, they live in 427 communal, autonomous, mostly prosperous agrarian “colonies” mainly in the Canadian Prairie provinces and the Northern Great Plains of the United States. The average colony size in 1979–1980 was 77 (5). The Hutterites have a relatively uniform environment, stemming from their austere lifestyle (3). Members of each colony share a communal kitchen, with uniform dietary habits. Children attend colony-managed schools until the age of 15, when they become full-time workers in the colony. Each member has a defined role, and an elected preacher is designated as the colony’s leader. Alcoholic beverages are used in moderation (3, 6). From a psychiatric perspective, the virtual absence of substance abuse makes the diagnosis of psychoses easier.

In Canada, extensive computerized psychiatric data are available from provincial health services, facilitating research on the epidemiology of several common multifactorial diseases among the Hutterites. Compared with the provincial population, the Hutterites showed no overall difference in the frequency of congenital anomalies, although the proportion of anomalies due to multifactorial disorders among Hutterites was low (6). In a study of the incidence of cancer among Hutterites in Alberta (7), the overall incidence of cancer among Hutterite women was lower than expected. The Hutterites consider smoking to be sinful. Not surprisingly, Hutterite men have a lower than expected rate of lung cancer. In contrast, the rates of stomach cancer and leukemia among Hutterite men were higher. In another study, the number of Hutterites with multiple sclerosis was much fewer than in a group of age-and sex-matched non-Hutterite neighbors (8). Subsequently, the prevalence of herpes simplex infections and cellulitis was reported to be higher among the Hutterites, whereas the prevalence of three infectious diseases (mumps, rubella, and acute coryza) was similar to that among comparison subjects, and the prevalene of nine other infectious diseases was reduced (9). Recently, regions of the genome harboring susceptibility genes for asthma have also been identified among the Hutterites (10). These studies document the differential prevalence of common diseases among the Hutterites, making them an ideal community for analysis of gene-environment interactions. Indeed, such investigations have already been conducted with respect to coronary heart disease (11).

History provides a comparison group for the communal Hutterites. Among the 1,265 Hutterite immigrants to North America, about two-thirds decided to homestead and settled on family farms. Such individuals, called “Prairieleut,” affiliated with nearby Mennonite groups (12) and married into the wider community. Patrilineal descendants from this group are identifiable by their surnames, and some reside in cities or on farms near Hutterite colonies in the province of Manitoba. They form the core of the comparison group for the study reported here, which also includes individuals who have Hutterite surnames but do not have Hutterite ancestry. Despite its mixed composition, this comparison group may be useful in an epidemiological study of the communal Hutterites, because the two groups share some ancestry but live in different environments and have different life styles.

Method

Two independent data sets were available for the study: 1) a comprehensive case-finding survey of all Hutterites living communally in the United States and Canada on January 1, 1950 (N=8,542) (13) and 2) a current health insurance claims database for Manitoba (fiscal years 1992/1993 through 1996/1997). Data from the former data set were obtained by one of the authors (J.E.). Permission for the anonymous search of the health insurance claims database was obtained from the University of Pittsburgh’s institutional review board, as well as Manitoba Health’s Access and Confidentiality Committee.

Epidemiological Survey (1950–1953)

Sources of data for the comprehensive case-finding survey conducted in the early 1950s included direct unstructured interviews, hospital records, and information from respondents’ relatives and community leaders. As part of the study reported here, the clinical records for individuals with any psychiatric illness were reviewed independently by one of the authors (V.L.N.) using DSM-IV criteria.

Health Care System Database (1992–1997)

Anonymous data for fiscal years 1992/1993–1996/1997 were obtained from Manitoba Health, which administers the universally accessible health care system in Manitoba. Health insurance claims are filed routinely for every hospital discharge, physician contact, outpatient visit, and admission to a personal care home (14). Records in the continuously updated database include the patient’s name, residential address, personal health identification number, and diagnosis.

The Hutterites reside in colonies with unique postal codes. There are 15 traditional family names among the Hutterites (4, 13). In a 1981 census database maintained by two of the authors (T.M.F. and K.M.), 99% of Manitoba Hutterites had one of the traditional surnames; the remaining 1% had other surnames. Thus, the Hutterite population in Manitoba was identified by searching Manitoba Health registration records, using the word “colony” in the address, not followed by the words “street,” “avenue,” or the like, followed by one of the unique postal codes. Cross-checking colony addresses with 19 Hutterite surnames (including rare and variant spellings) gave estimates for the number of Hutterites residing in the colonies. Persons with one of the 19 surnames but with noncolony residential addresses may include Prairieleut and Hutterites who left the colony and their descendants, and we refer to this group as a “comparison” group. Population estimates by six age groups for the Hutterites, the comparison group, and the entire province were also available from Manitoba Health.

For each of these three groups, patient counts were obtained from the health insurance claims database, by sorting the relevant ICD-9 diagnoses-related record by personal health identification number. Patient counts were available for the three-digit categories for psychoses (ICD 290–299), for neurotic disorders (ICD 300), and for adjustment reaction (ICD 309) by six age groups (0–9, 10–19, 20–34, 35–54, 55–79, and 80 years or older). Multiple claims for the same diagnosis for the same individual were ignored, so that no disease was counted more than once for any person in any given year.

Population Comparisons

In the 1990s the Hutterite population comprised 0.6% of the total Manitoba population and had a younger age distribution. For example, the proportion of the population less than 20 years of age was 46% for the Hutterites compared to 29% for the total Manitoba population. To take into account the different age distributions while comparing prevalence rates among the Hutterites with those in the Manitoba population, we predicted the number of cases among the Hutterites for each year by applying the age-specific rates for broad age groups in the total Manitoba population to the Hutterite population in the corresponding age groups and summing over the age groups. Similarly, we predicted the number of cases in the comparison group by using the age-specific rates of the total Manitoba population.

Due to the small number of observed cases for some disease categories, we made a category called “other functional psychoses” that comprised ICD-9 codes 297–299 (paranoid states, other nonorganic psychoses, and psychoses with origin specific to childhood, respectively) and another category called “organic psychotic conditions” that comprised ICD-9 codes 290–294 (senile and presenile organic psychotic conditions, alcoholic psychoses, drug psychoses, transient organic psychotic conditions, and other chronic organic psychotic conditions, respectively).

Statistical significance was assessed in two ways. The observed rate was considered to be binomially distributed. The smallest number for which the cumulative binomial distribution was greater than or equal to the 95% value was calculated using the CRITBINOM function in Microsoft Excel 97. If the predicted number of cases for a particular disease was beyond the 95% value, we considered the observed rate to be significantly less than the rate in the total Manitoba population. For neurotic disorders, where the observed numbers were large, the observed number was considered to be significantly different than expected if the predicted number was outside the 95% confidence interval (CI).

Statistical significance of the ratio of the observed to predicted rates was assessed by determining if it fell outside the 95% confidence limits for the observed ratio (15). The number of observed cases of any particular disease was considered to be Poisson-distributed, and the expected number was considered to be the predicted number.

Results

Prevalence Rates

Epidemiological survey

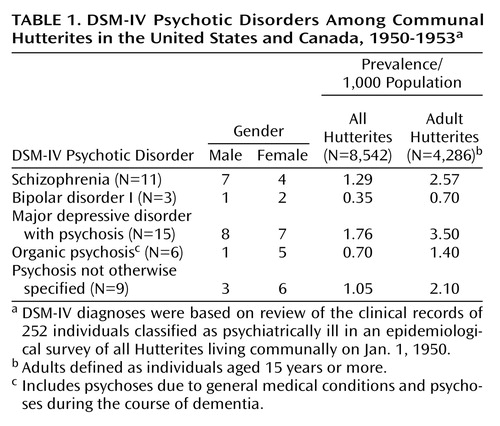

In the 1950–1953 study, 252 individuals were classified as psychiatrically ill; 44 of those 252 individuals had psychoses (presence of delusions, hallucinations, or formal thought disorder). The prevalence rates for DSM-IV psychoses, based on a review of the records for all 252 psychiatrically ill individuals by one of the authors, are shown in Table 1. We used the term “organic psychoses” for psychoses due to general medical conditions and psychoses occurring during the course of dementia. Because psychotic illnesses are uncommon in childhood, prevalence figures based on an adult population base (individuals over 15 years of age) are also presented. These rates are somewhat lower than estimates using DSM-III-R criteria (2). Nine of the 11 individuals with DSM-IV schizophrenia had been hospitalized before the survey. The ages at onset for these 11 cases were 15–25 years for six individuals, 25–29 years for four, and 35–44 years for one.

Health care system database

Population estimates for the five fiscal years (1992/1993–1996/1997) were obtained from the computerized database search. The annual total mean population sizes were 1,141,476 for Manitoba province (range=1,133,120–1,146,995), 7,020 for the Hutterites (range=6,584–7,459), 2,888 for the comparison group (range=2,820–2,969), and 52 for individuals with non-Hutterite surnames who had Hutterite colony postal codes (range=51–57). The small number of individuals in the latter group was not included in the Hutterite population.

Prevalence rates for psychoses were lower in both the Hutterites and the comparison group, compared with the Manitoba population (Table 2). By contrast, the prevalence of neurotic disorders was higher among both the Hutterites and the comparison group, compared with the Manitoba population. The prevalence of adjustment reaction disorders differed greatly between the Hutterites and the comparison group; it was lower in the former but higher in the latter group, compared with the Manitoba population.

Observed and Predicted Prevalence Rates

To take into account the differing age distributions, we predicted the number of cases among the Hutterites and the comparison group, assuming the age-specific rates in the Manitoba population (Table 2). We applied the rate of each of six age groups in the Manitoba population to the number of Hutterites in the corresponding age groups and accumulated the predicted numbers over the age groups. To test if the predicted numbers differed from the observed numbers, we determined if the 95% confidence interval of the ratio excluded 1. For the Hutterites, the ratio of the observed to the predicted number was significantly less than 1 for all psychoses except the category of organic psychotic conditions (senile and presenile, alcoholic, drug, transient organic, and other chronic organic psychoses) and for adjustment reaction disorders. That is, the Hutterites had significantly fewer persons with psychoses, most notably schizophrenia and affective psychoses, than expected on the basis of the provincial rate. The fewer observed than predicted numbers in the category other functional psychoses was due to other nonorganic psychoses (ICD 298), a category for psychotic conditions largely attributable to a recent life experience. For the other two illnesses in the category of other functional psychoses (paranoid states and psychoses with origin specific to childhood), there was a maximum of only one observed case and three predicted cases. In striking contrast, the Hutterites had significantly more persons with neurotic disorders than predicted.

The pattern of psychoses in the comparison group was similar to that of the Hutterites, but the observed numbers were significantly fewer than predicted only for schizophrenia and the category of other functional psychoses. As among the Hutterites, the comparison group had significantly more persons with neurotic disorders than predicted. However, these two groups differed for adjustment reaction disorders; there were significantly fewer cases among the Hutterites and significantly more cases in the comparison group than predicted.

Statistical comparison of prevalence rates between the Hutterites and the comparison group was not feasible due to the relatively small numbers in each group.

Discussion

Previous studies have documented a low prevalence of psychoses in Taiwan and within Papua New Guinea (16, 17). A similar trend among the Hutterites was examined more comprehensively here. Four sets of observations emerged. First, the prevalence rate for schizophrenia among the Hutterites in the 1990s was comparable to the estimate from an earlier epidemiological survey in the 1950s, even though different ascertainment and diagnostic criteria were used in the two time periods. Second, prevalence rates of several psychoses were lower among the Hutterites, compared with the Manitoba population. Third, the lower rates were statistically significant for selected diagnoses, suggesting specificity. The reduced prevalence was evident both among the communal Hutterites and in the comparison group of individuals with Hutterite surnames living in the wider community. Fourth, prevalence rates for neurotic disorders among both the Hutterites and the comparison group were higher than in the Manitoba population.

Before the low prevalence for psychoses can be linked to etiological factors, one must consider spurious artifacts, such as incomplete ascertainment. Do Hutterites evade conventional treatment for psychiatric conditions due to stigmatization? The 1950–1953 case-finding survey revealed that more than 80% of persons with identified cases with schizophrenia had been hospitalized, suggesting not only that ascertainment was comprehensive but also that most Hutterites with schizophrenia received conventional treatment even then. The recent database survey, which was extended to five annual periods to maximize detection, yielded estimates for schizophrenia similar to the prior survey. Hutterites seek out medical care and even spend their own funds for nonconventional treatment of severely ill community members. Indeed, independent systematic surveys indicate that adult Hutterites seek medical care more often than non-Hutterites (8). Local physicians have noted that Hutterites tend to seek help early in an illness rather than late (J. Price, R.T. Ross, personal communication, 1999). Indeed, in the study reported here, the prevalence rate for neurotic disorders was higher among the Hutterites, suggesting that treatment was not underutilized by Hutterites with psychiatric disorders. Finally, the lower prevalence rate for psychoses in the comparison group is interesting. This heterogeneous group shares the residential environment of the general population, where severe psychiatric illnesses such as schizophrenia are likely to come to the attention of health care agencies. Thus, the likelihood of incomplete ascertainment in this group was low.

Do the Hutterites have culturally shared beliefs that could be viewed as delusional or hallucinatory by Western psychiatrists? Do culture-bound syndromes that cannot be classified by using conventional diagnostic criteria exist in the group? We are aware of only one such condition. The Hutterites use the term “Anfechtung” to describe a malady closely related to depression or anxiety. It involves rumination on religious issues, feelings of guilt, and inability to work. Such individuals may receive counseling from preachers and elders. In our experience, obvious behavioral abnormalities or conditions refractory to religious counseling are usually brought to the attention of psychiatrists. Indeed, a Hutterite elder’s informal estimates of the number of Hutterites with psychoses in the Manitoba colonies were consistent with the estimates reported in Table 2 (data not shown).

The prevalence of psychoses could also be underestimated if Hutterites sought treatment outside Manitoba. Hutterites will pay for medical treatment outside the province for seriously ill people only if they are not satisfied with treatment provided by Manitoba physicians. Thus, data for individuals treated outside Manitoba should first be recorded in the Manitoba Health database, their initial treatment in Manitoba is free of charge. Even if treatment outside Manitoba affected the results reported here, it is difficult to see why such treatment would be sought selectively only for certain mental disorders. Such biases would also be less likely for the comparison group, who do not have a Hutterite life style but nevertheless have low prevalence rates of psychoses.

The utility and validity of the Manitoba Health database for similar studies has been previously demonstrated. For example, Ross et al. (8) found that during 1986–1991 the prevalence of multiple sclerosis as well as infection with herpes zoster and varicella were lower among the Hutterites, compared with a non-Hutterite comparison group matched for age, gender, and residential area. The prevalence of six of seven neurological diseases in the two groups was not significantly different. The selective reduction for certain diseases suggests that information about Hutterites is not systematically underreported in the Manitoba Health database. One of the disease categories in this earlier study (depressive psychoses) corresponds to ICD-9 code 298, other nonorganic psychoses, which was included in our study. In contrast to our findings, Ross et al. reported no significant difference in prevalence for this category between the Hutterites and their non-Hutterite neighbors. The discrepancy may be explained by differences in the comparison subjects, the study design, and the time period (the study by Ross et al. covered the 7 years before the period covered in our study).

Previous studies suggest elevated rates of schizophrenia in certain immigrant groups (18). The reduced rate among the Hutterites is unlikely to be due to disproportionate emigration of individuals with schizophrenia from the colonies. These individuals should have been ascertained in the comparison group. However, the prevalence in the comparison group was not elevated and was the lowest among the three groups. Others have noted that permanent defection from the colonies is uncommon (12). Hutterites who leave colonies usually remain in the province. Given the support structure provided by the Hutterite life style, a Hutterite with a psychiatric disorder is likely to remain in the colony.

Manitoba psychiatrists may have misdiagnosed psychoses as neuroses among the Hutterites, who are identifiable by their distinctive garments and their residential addresses. However, low rates were also found in the comparison group, who do not wear distinctive clothes and do not live in colonies. The hypothesis that diagnostic bias contributed to the lower rates of psychoses is therefore untenable.

The diagnostic system used in the database search (ICD-9) has been superseded. Fortunately, clinical records from the previous Hutterite survey were available (13). Although the survey was conducted more than four decades ago, it attempted complete ascertainment. Rediagnosis of cases identified in this survey using current diagnostic criteria (DSM-IV) would thus provide another reliable population estimate. We found that the prevalence figures for schizophrenia on the basis of rediagnosis are in agreement with the estimates from the Manitoba Health database.

Other methodological issues deserve comment. The important questions of gender differences and age at onset are unresolved for the database survey (1992/1993–1996/1997). This information was not released by Manitoba Health because of concerns about confidentiality. However, the gender distribution and the ages at onset of illness for the individuals with schizophrenia in the 1950–1953 survey are consistent with those in other populations (19). The database survey also focused on one of three subgroups of Hutterites (the Schmiedeleut in Manitoba). It is not known if our findings extend to the other two subgroups. The annual prevalence estimates among the Hutterites varied, especially the estimates for uncommon disorders. However, no systematic trends in the annual estimates were noted. Despite the variability, consistent differences between the general population and the Hutterites or the comparison group were noted.

A previous study did not find differences in the prevalence of affective disorders among the Hutterites, compared with the Canadian population (20). The reliability of the previous study is unclear because it was based on hospital admission rates. Moreover, that study classified the Hutterites with the Mennonites, a distinct group with a different life style and genetic background.

Thus, the differences between the Hutterites and non-Hutterites are most likely not spurious. A number of causes for the differences merit consideration. Could environmental or cultural factors be at work? Prior studies have highlighted the familial and community support available for Hutterites (21). Such extensive support may play a protective role. Alternatively, stressful life events, known to precipitate schizophrenia, may be less common among the Hutterites. In support of this interpretation, the prevalence of adjustment reactions was lower among the Hutterites than in the Manitoba population (Table 2).

Genetic factors may play an important role in the reduced prevalence of psychoses among the Hutterites. Reduced prevalence was also noted in the comparison group who may share ancestry with the Hutterites. A low frequency of psychosis-predisposing alleles must be suspected. Fewer susceptibility alleles may have been introduced by chance into the Hutterite population by the relatively small number of founders. In addition, dominant susceptibility alleles would be easily lost from the population if there was reduced fertility, as has been shown for schizophrenia. Alternatively, there may be a relative increase in protective alleles segregating in this highly inbred population. Finally, gene-environment interactions are plausible.

A number of statistical tests were performed in the study reported here. Thus, some of the results may have reached statistical significance by chance alone. Therefore, we want to emphasize the pattern of reduced prevalence of psychoses among both the Hutterites and the comparison group, compared to the Manitoba population. A detailed study of genetic and environmental factors among the Hutterites is warranted to uncover both risk factors and protective factors for schizophrenia and affective disorders.

|

|

Presented as a poster at the World Congress of Psychiatric Genetics, Bonn, Oct. 6–10, 1998. Received Nov. 9, 1998; revision received Oct. 13, 1999; accepted Dec. 22, 1999. From the Departments of Psychiatry and Human Genetics, University of Pittsburgh School of Medicine, Western Psychiatric Institute and Clinic, Pittsburgh; Departments of Human Genetics and Medicine, McGill University and the McGill University Health Centre, Montreal; and Health Information Services, Manitoba Health, Winnipeg. Address reprint requests to Dr. Nimgaonkar, WPIC, Room 443, 3811 O’Hara St., Pittsburgh, PA 15213; [email protected] (e-mail). Supported in part by grants from the Stanley Foundation, NIMH grant MH-01489 (Dr. Nimgaonkar), Mental Health International Research Center grant MH-30915, and the Canadian Genetic Diseases Network, Networks of Centres of Excellence (Dr. Morgan).

1. Eaton JW, Weil RJ: Culture and Mental Disorders. Glencoe, Ill, Free Press, 1955Google Scholar

2. Torrey EF: Prevalence of psychosis among the Hutterites: a reanalysis of the 1950–53 study. Schizophr Res 1995; 16:167–170Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

3. Hostetler JA: History and relevance of the Hutterite population for genetic studies. Am J Med Genet 1985; 22:453–462Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

4. Eaton JW, Mayer AJ: Man’s Capacity to Reproduce: The Demography of a Unique Population. Glencoe, Ill, Free Press, 1954Google Scholar

5. Hofer J, Wiebe D, Gerhard ENS: The History of the Hutterites. Winnipeg, Manitoba, Canada, WK Printers’ Aid, 1982Google Scholar

6. Lowry RB, Morgan K, Holmes TM, Gilroy SW: Congenital anomalies in the Hutterite population: a preliminary survey and hypothesis. Am J Med Genet 1985; 22:545–552Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

7. Gaudette LA, Holmes TM, Laing LM, Morgan K, Grace MG: Cancer incidence in a religious isolate of Alberta, Canada, 1953–74. J Natl Cancer Inst 1978; 60:1233–1238Google Scholar

8. Ross RT, Nicolle LE, Cheang M: Varicella zoster virus and multiple sclerosis in a Hutterite population. J Clin Epidemiol 1995; 48:1319–1324Google Scholar

9. Ross RT, Cheang M: Common infectious diseases in a population with low multiple sclerosis and varicella occurrence. J Clin Epidemiol 1997; 50:337–339Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

10. Ober C, Cox NJ, Abney M, Di Rienzo A, Lander ES, Changyaleket B, Gidley H, Kurtz B, Lee J, Nance M, Pettersson A, Prescott J, Richardson A, Schlenker E, Summerhill E, Willadsen S, Parry R: Genome-wide search for asthma susceptibility loci in a founder population: the Collaborative Study on the Genetics of Asthma. Hum Mol Genet 1998; 7:1393–1398Google Scholar

11. Hegele RA, Evans AJ, Tu L, Ip G, Brunt JH, Connelly PW: A gene-gender interaction affecting plasma lipoproteins in a genetic isolate. Arterioscl Thromb 1994; 14:671–678Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

12. Hostetler J, Huntington GE: The Hutterites in North America, 3rd ed. New York, Harcourt Brace College, 1996Google Scholar

13. Eaton JW, Weil RJ: The mental health of the Hutterites. Sci Am 1953; 189:31–38Crossref, Google Scholar

14. Roos LL Jr, Nicol JP, Cageorge SM: Using administrative data for longitudinal research: comparisons with primary data collection. J Chronic Dis 1987; 40:41–49Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

15. Bailar JC III, Ederer F: Significance factors for the ratio of a Poisson variable to its expectation. Biometrics 1964; 20:639–643Crossref, Google Scholar

16. Lin TY, Chu HM, Rin H, Hsu CC, Yeh EK, Chen CC: Effects of social change on mental disorders in Taiwan: observations based on a 15-year follow-up survey of general populations in three communities. Acta Psychiatr Scand Suppl 1989; 348:11–33; discussion, 348:167–178Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

17. Torrey EF, Torrey BB, Burton-Bradley BG: The epidemiology of schizophrenia in Papua New Guinea. Am J Psychiatry 1974; 131:567–573Link, Google Scholar

18. Harrison G, Owens D, Holten A, Neilson D, Boot D: A prospective study of severe mental disorder in Afro-Caribbean patients. Psychol Med 1988; 18:643–657Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

19. Carpenter WT, Buchanan RW: Medical progress: schizophrenia. N Eng J Med 1994; 330:681–690Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

20. Murphy HBM: European cultural offshoots in the new world: differences in their mental hospitalization patterns, part II: German, Dutch, and Scandinavian influences. Arch Psychiatr Nervenkr 1980; 228:161–174Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

21. Eaton JW: Folk psychiatry. New Society 1963; 48:9–11Google Scholar