Quality of Life in Individuals With Anxiety Disorders

Abstract

OBJECTIVE: Quality-of-life indices have been used in medical practice to estimate the impact of different diseases on functioning and well-being and to compare outcomes between different treatment modalities. An integrated view of the issue of quality of life in patients with anxiety disorders can provide important information regarding the nature and extent of the burden associated with these disorders and may be useful in the development of strategies to deal with it.METHOD: A review of epidemiological and clinical studies that have investigated quality of life (broadly conceptualized) in patients with panic disorder, social phobia, posttraumatic stress disorder, generalized anxiety disorder, and obsessive-compulsive disorder was conducted by searching MEDLINE and PsycLIT citations from 1984 to 1999. A summary of the key articles published in this area is presented.RESULTS: The studies reviewed portray an almost uniform picture of anxiety disorders as illnesses that markedly compromise quality of life and psychosocial functioning. Significant impairment can also be found in individuals with subthreshold forms of anxiety disorders. Effective pharmacological or psychotherapeutic treatment has been shown to improve the quality of life for patients with panic disorder, social phobia, and posttraumatic stress disorder. Limitations in current knowledge in this area are identified, and suggestions for needed future research are provided.CONCLUSIONS: It is expected that a more thorough understanding of the impact on quality of life will lead to increased public awareness of anxiety disorders as serious mental disorders worthy of further investment in research, prevention, and treatment.

Anxiety disorders were described as early as the fourth century B.C. in the writings of Hippocrates (1), but their importance was not fully appreciated until less than 30 years ago. For complex historical reasons the first specialists in psychiatry, the alienists of the early nineteenth century, were mainly concerned with the description and classification of psychotic disorders. As a result, the development of the field of anxiety disorders (as well as the domains of somatization and conversion disorders) was left to specialists in internal medicine and neurology such as da Silva, Briquet, Beard, Charcot, and Freud (2). The interest of mainstream psychiatry in anxiety disorders would remain limited throughout the first half of the twentieth century because of the prevailing belief that neurotic disorders were benign conditions with nonorganic causes and that their treatment should necessarily be based on some form of psychotherapy (3).

The realization that anxiety disorders could be successfully treated by pharmacological means (4), the development of reliable diagnostic criteria (5), and the advent of modern psychiatric nosology set the stage for a critical reappraisal of the magnitude of the problem of anxiety disorders. Using the DSM-III criteria, the National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH) Epidemiologic Catchment Area (ECA) study showed that anxiety disorders had the highest overall prevalence rate among the mental disorders, with a 6-month rate of 8.9% and a lifetime rate of 14.6% (1), and affected 26.9 million individuals in the United States at some point in their lives. The costs associated with anxiety disorders in 1990 were a staggering $46.6 billion, accounting for 31.5% of total expenditures in that year for mental health (6).

Quality of Life: The Concept

It is often said that the cost of human suffering cannot be measured. This truism may no longer be accurate. Many aspects of human suffering (or its absence) can be reliably measured. One of the approaches to this difficult yet invaluable task makes use of the concept of “quality of life.” This concept, developed in the social sciences, was first applied in medical practice to determine if available cancer treatments could not only increase the survival time of patients but also improve their sense of well-being (7). The concept of quality of life was later applied to compare several antihypertensive medications in terms of functioning, well-being, and life satisfaction (8).

According to Patrick and Erickson (9), life has two dimensions: quantity and quality. Quantity of life is expressed in terms of “hard” biomedical data, such as mortality rates or life expectancy. Quality of life refers to complex aspects of life that cannot be expressed by using only quantifiable indicators; it describes an ultimately subjective evaluation of life in general. It encompasses, though, not only the subjective sense of well-being but also objective indicators such as health status and external life situations (10). Data about quality of life can be used to estimate the impact of different diseases on functioning and well-being, to compare outcomes between different treatment modalities (such as medication and surgery), and, as in the examples mentioned, to differentiate between two therapies with marginal differences in mortality and/or morbidity (11).

No single definition of quality of life is universally accepted (12). There is, however, a degree of consensus regarding the minimal requirements for an operational definition of quality of life for employment in health status assessment and research. First, most experts agree that the scope of the concept of quality of life should be centered on the individual’s subjective perception of the quality of his or her own life. This consensus stems from the findings of several sociological studies that have demonstrated that objective conditions of life such as education and income are only marginally related to the subjective experience of a higher quality of life (13, 14). Second, most authors agree that given the difficulties in assessing the relative impact of the complex experiences that ultimately determine one’s perception of quality of life, quality of life is better approached as a multidimensional construct, covering a certain number of conventionally defined domains (15). Finally, it is recommended that we avoid the vagaries of abstract and philosophical concepts and concentrate on aspects of personal experience that are related to health and health care (health-related quality of life) (16).

An example of a subjective multidimensional definition of health-related quality of life was proposed by Patrick and Erickson (17): “the value assigned to the duration of life as modified by the social opportunities, perceptions, functional states, and impairments that are influenced by disease, injuries, treatments, or policies” (p. 6). Aaronson et al. (18) suggested that the assessment of quality of life should comprise at least the following four domains: 1) physical functional status, 2) disease- and treatment-related physical symptoms, 3) psychological functioning, and 4) social functioning. Additional domains that are of particular relevance to specific demographic, cultural, or clinical populations (such as sexual function, body image, or sleep) may sometimes need to be included in the assessment to increase the breadth of coverage (19).

Approaches to Studying Quality of Life in Individuals With Anxiety Disorders

Data regarding quality of life in mental disorders in general, and in anxiety disorders in particular, derive from two types of sources. The first source is represented by epidemiological studies such as the ECA and the National Comorbidity Survey. Although these studies were not specifically designed to study the association between quality of life and mental disorders in the community, they provide a number of indicators from which quality of life can be inferred. These indicators include a subjective assessment of physical and emotional health, psychosocial functioning, and financial dependency (1, 20, 21).

Clinical studies made by using specifically designed instruments represent the second major source of data concerning quality of life. These instruments may be generic (i.e., attempting to measure multiple important aspects of quality of life) or specific (i.e., focusing on aspects of health status that are specific to the area of primary interest). The latter may be specific to a disease (e.g., panic disorder), to a population (e.g., elderly patients), to a function (e.g., sleep), or to a problem (e.g., pain) (22). The main advantage of generic measures is that they permit comparisons across conditions and populations. In contrast, specific measures are intended to detect small, meaningful changes in specific conditions to which generic measures may be insensitive.

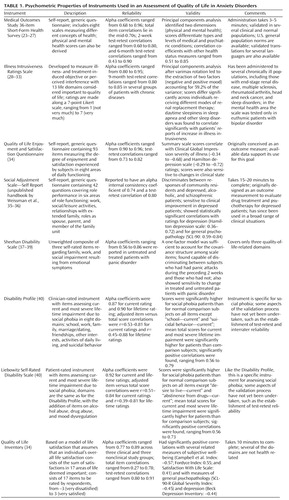

Although quality-of-life data can be collected in interviews or through patient diaries, most studies now employ self-report questionnaires, the most cost-effective method for obtaining patient-related information (19). For this report, a review of epidemiological and clinical studies that have investigated quality of life (broadly conceptualized) in patients with panic disorder, social phobia, posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD), generalized anxiety disorder, and obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD) was conducted by searching MEDLINE and PsycLIT from Jan. 1984 to Oct. 1999. The key words employed were “quality of life,” “impairment,” and “disability.” With few exceptions (to be discussed later), only clinical studies utilizing self-report instruments based on subjective, multidimensional concepts of health-related quality of life that were properly validated were considered. (Table 1 briefly summarizes the psychometric properties of these instruments.)

Quality of Life in Individuals With Panic Disorder

Studies in Community Samples

The ECA study is an important source of data regarding the epidemiology of panic disorder and the impact of panic disorder on quality of life. This study found a lifetime prevalence for panic disorder of 1.5% (21). The domains of quality of life assessed were the subjective reporting of health, psychosocial functioning, and financial dependency. Quality-of-life measures in persons with lifetime panic disorder were compared with those of persons with lifetime major depression—a condition whose social morbidity is well documented (41, 42)—and subjects with neither disorder (21, 43).

Among persons with panic disorder in the community, 35% felt they were in fair or poor physical health, and 38% felt they were in poor emotional health (21). Individuals with major depression showed similar rates (29% and 39%, respectively), whereas those with neither disorder had significantly lower levels of negative perceptions of their physical and mental health (24% and 16%). A total of 27% of the persons with panic disorder were receiving welfare or some form of disability compensation, a significantly higher proportion than that found among persons with major depression (16%) and with neither disorder (12%).

Infrequent Panic Attacks and Quality of Life

Persons with panic attacks that did not meet the full DSM-III criteria for panic disorder because of insufficient frequency of attacks or symptoms (“infrequent” panic attacks: lifetime prevalence=3.6%) also showed substantial impairment in perceived physical and emotional health, occupational functioning, and financial independence. Klerman and colleagues (44) noted that on almost any measure, subjects with panic attacks were intermediate in severity between those who met the full criteria for panic disorder and those with no disorder. These findings were consistent with Gelder’s observation (45) that the difference between subjects with panic disorder and with panic attacks is more quantitative than qualitative. Since the lifetime prevalence of panic attacks in the general population is more than twice as high as that of panic disorder (7.3% and 3.5%, respectively, in the National Comorbidity Survey [46]), panic attacks are more likely to be associated with a higher population-attributable risk of decrements in social and vocational function than panic disorder itself (47).

Studies in Clinical Samples

The most widely used instrument currently employed to measure quality of life is the Medical Outcomes Study 36-item Short-Form Health Survey (23). It assesses two broad dimensions—mental health and physical health—each consisting of four specific domains (i.e., eight total): physical functioning, role limitations due to physical health problems, bodily pain, social functioning, general mental health (covering psychological distress and well-being), role limitations due to emotional problems, vitality, and general health perceptions. Norms are available for the general U.S. population as well as for several medical conditions (48).

Sherbourne and colleagues (49) used the Short-Form Health Survey to compare the quality of life of patients with current panic disorder to that of patients with depression or chronic medical conditions such as hypertension, diabetes (type I or II), heart disease, arthritis, and chronic lung disease. In this study panic disorder emerged as associated with high psychological distress and limitations in role functioning but with relatively preserved physical functioning. In contrast, patients with depression showed limitations in all domains of functioning that were as great as or greater than the limitations associated with most chronic medical diseases.

The findings of Sherbourne and colleagues (49) are consistent with those of several other studies using the Short-Form Health Survey. Numerous investigators (47, 50–54) clearly documented a decreased quality of life in patients with panic disorder compared to normal subjects. Four studies (47, 50, 51, 54) found significant impairment in scores on the physical functioning subscales of the Short-Form Health Survey, as well as in scores on the mental health functioning subscales for patients with panic disorder. Schonfeld and colleagues (51) also found that major depression had a far greater impact on scores for subscales of the Short-Form Health Survey than any anxiety disorder, including panic disorder. These findings, like the epidemiologic findings cited previously, place the quality of life in patients with panic disorder as better than that of patients with major depression but still markedly lower than that of otherwise healthy individuals.

The publication of numerous validation studies, availability of general population norms, and ease of administration make the Short-Form Health Survey a very attractive option for the measurement of quality of life in persons with anxiety disorders. Nonetheless, it should be noted that making statistical comparisons by using the Short-Form Health Survey may not be straightforward (55). Six of the eight scales of the Short-Form Health Survey have continuous variables, with scores ranging from 0 to 100. Scores on these measures in the general population, however, tend to be skewed to the left, with a majority of individuals showing a relatively high quality of life. The two remaining scales—role limitations due to physical health problems and role limitations due to emotional problems—are categorical. Thus, comparisons of scores on the Short-Form Health Survey in patient groups with population norms may be methodologically complicated, requiring the use of nonparametric tests or logarithmic or z transformations to obtain a more normal distribution. These procedures, however, have been seldom reported in the literature concerning anxiety disorders to date.

Impact of Treatment on Quality of Life in Patients With Panic Disorder

A growing number of clinical trials have incorporated quality-of-life assessment as an outcome measure in the treatment of panic disorder. The measurement of quality of life in clinical trials represents a special situation, imposing specific requirements on the instruments to be employed. For evaluative purposes it is essential to demonstrate that the instrument is capable of measuring the magnitude of the longitudinal changes on the dimension of interest in an individual or group exposed to a specific intervention. This property is called sensitivity to change, or responsiveness. For measures that are to be administered repeatedly, it is important that the instrument have very good reliability. Characteristics such as reliability and responsiveness may be difficult to reconcile in a single instrument, particularly in generic instruments intended to cover extensive domains. As shown in the descriptions of studies to follow, the Short-Form Health Survey seems to perform admirably in these respects. The sensitivity to change of the Sheehan Disability Scale (37), Social Adjustment Scale (unpublished handbook by Weissman et al.), and Quality of Life Enjoyment and Satisfaction Questionnaire (34) have been demonstrated, which supports their use in clinical trials.

Another important characteristic of an instrument is its interpretability. For evaluative purposes, one should be able to interpret changes in the instrument’s scores in terms of their relevance (or lack thereof) for the health status of a patient. Although clinicians can easily interpret the implications of a change in the number of panic attacks per day or in the percentage of time spent worrying about having a panic attack, the meaning of a change in the score on a quality-of-life instrument may remain obscure unless some standard is provided. To our knowledge, only the Short-Form Health Survey provides standards for comparing clinical changes across several clinical conditions, as seen in the study by Jacobs et al. (56), to be described. We will summarize results from studies of panic disorder outcomes according to the main quality-of-life measure(s) employed.

Outcome studies using the Short-Form Health Survey

Mavissakalian et al. (57) treated 110 patients with moderate-to-severe panic disorder, including agoraphobia, with a fixed regimen of imipramine, 2.25 mg/day per kg of body weight for 24 weeks. The Short-Form Health Survey was administered at pretreatment and at week 16. A total of 53% of the patients had a marked and stable response. Completers (N=59) and noncompleters (N=51) had equivalent scores on a baseline Short-Form Health Survey, except on the pain subscale, on which completers scored significantly lower than noncompleters. At week 16 the completers showed significant improvements on all subscales, particularly on role limitations (emotional), energy, social functioning, and mental health.

Jacobs et al. (56) examined the effects of clonazepam and placebo on scores for patients with panic disorder on the Short-Form Health Survey in a double-blind, controlled trial. Quality-of-life assessments were made at baseline and after 6 weeks of therapy (or at premature termination from the study). Between-group comparisons showed that clonazepam-treated patients (N=71) had a significant improvement in scores on the Short-Form Health Survey mental health component summary (which aggregates the scores of the four subscales measuring mental and emotional health) compared to placebo-treated subjects (N=68) after 6 weeks of treatment. Scores on the mental health component summary were found to be strongly related to clinical measures, with patients reporting marked improvement in avoidance and fear also showing the strongest mental health component summary score gains. The authors observed that the 8.9-point gain in scores on the mental health component summary observed in the clonazepam group was comparable to the 10.9-point improvement reported for recovered depressive individuals.

Outcome studies using the Quality of Life Enjoyment and Satisfaction Questionnaire

The Quality of Life Enjoyment and Satisfaction Questionnaire is a validated quality-of-life scale that rates eight aspects of quality of life, including physical health, subjective feelings, activities of daily living, and overall life satisfaction (34).

Pohl et al. (58) and Pollack et al. (59) conducted a 10-week, randomized, double-blind study comparing the effects of sertraline and placebo in over 150 outpatients with a DSM-III-R diagnosis of panic disorder with or without agoraphobia. At the beginning and end of the double-blind phase the patients completed the Quality of Life Enjoyment and Satisfaction Questionnaire. In both studies, in addition to experiencing fewer panic attacks, sertraline-treated patients exhibited a statistically significant increase (change from baseline) in scores on the Quality of Life Enjoyment and Satisfaction Questionnaire for total and overall life satisfaction compared with placebo-treated patients.

Outcome studies using the Sheehan Disability Scale

The Sheehan Disability Scale is a three-item self-report that assesses impairment in work activities, social life and leisure activities, and family life and home responsibilities (38).

Three studies have compared selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) to placebo in randomized, controlled studies for the treatment of panic disorder. Hoehn-Saric et al. (60) compared fluvoxamine with placebo in 50 patients with panic disorder over 8 weeks and failed to find statistically significant group differences among scores on the Sheehan Disability Scale. The authors suggested that a longer follow-up period might be needed to detect improvements in social adjustment. Lecrubier et al. (61) compared the effects of placebo, paroxetine, and clomipramine in 367 patients with panic disorder. At week 9, patients treated with paroxetine (N=123) and clomipramine (N=121) showed significantly larger increases from baseline in scores on the three Sheehan Disability Scale items than placebo-treated subjects (N=123); there were no significant differences between scores for groups treated with paroxetine or clomipramine on any Sheehan Disability Scale items. Michelson et al. (62) compared groups receiving 10 mg/day or 20 mg/day of fluoxetine to a placebo group among 243 patients with a diagnosis of panic disorder. After 10 weeks of therapy, functional impairment, as measured by the Sheehan Disability Scale, was significantly more improved on items for family life (for groups receiving 10 or 20 mg/day of fluoxetine) and social life (for the group receiving 10 mg/day of fluoxetine) in the fluoxetine groups than in the placebo group. Reduction in the frequency of panic attacks was found to correlate poorly with ratings on the Sheehan Disability Scale and other secondary outcome measures, which suggests that the impairment associated with panic disorder may result primarily from other symptom domains, such as phobic avoidance and depression.

Outcome studies using the Social Adjustment Scale—Self-Report

The Social Adjustment Scale—Self-Report is a 42-item, self-report instrument measuring either instrumental or expressive role performance over the past 2 weeks in six major areas of functioning. It was originally designed as an outcome measurement to evaluate psychotherapy and drug treatment for depressed patients (35).

To our knowledge, only one study has employed quality of life as an outcome measure for the treatment of patients with panic disorder with cognitive behavior therapy. Telch et al. (63) randomly assigned 156 outpatients meeting the DSM-III-R criteria for panic disorder with agoraphobia to group cognitive behavioral therapy or to a delayed-treatment control condition. An assessment battery including two measures relevant to the assessment of quality of life, the Social Adjustment Scale—Self-Report and the Sheehan Disability Scale, was administered at baseline (week 0), posttreatment (week 9), and 6-month follow-up. Consistent with results from previous studies, patients with panic disorder showed a significant impairment in quality of life at baseline. Treated subjects displayed significantly less impairment on the Social Adjustment Scale—Self-Report scale measuring work outside and inside the home, social and leisure activities, marital and extended family relationships, and overall functioning and on the Sheehan Disability Scale items measuring family and social functioning, work functioning, and global functioning. Anxiety and phobic avoidance were shown to be significantly associated with quality of life, whereas the frequency of panic attacks was not. The authors hypothesized that the infrequency and transient nature of panic attacks may lead to less impairment than the more chronic and pervasive symptoms of anxiety and agoraphobic avoidance. These conclusions are supported by the findings of other groups that employed the Sheehan Disability Scale to measure impairment in patients with panic disorder, such as Michelson et al. (62), just mentioned, and Leon et al. (64), who found that the frequency of panic attacks accounts for no more than 12% of the variance in impairment.

Quality of Life in Individuals With Social Phobia

Although social phobia is not a newly recognized disorder (65), the magnitude of the problem was not fully appreciated until the late 1980s, leading to social phobia being termed a “neglected anxiety disorder” (66). Even mental health specialists may have felt at first that this disorder, then just recently included in the DSM-III, represented an undue extension of the medical model into the domain of a naturally occurring phenomenon—shyness. Also, the first clinical studies comparing patients with social phobia and panic disorder reported that patients with social phobia tended to be men with higher educational, intellectual, social, and occupational status (67–69), suggesting that social phobia was a relatively benign condition. It was not until the ECA findings were reported (70) that a different profile emerged, showing social phobia to be a common disorder associated with significant disability and impairment.

Studies in Epidemiologic Samples

Although the ECA study did not include direct measures of quality of life, many of the areas surveyed by the ECA are relevant to this issue. For example, the rate of financial dependency among subjects with uncomplicated social phobia (22.3%) was found to be significantly elevated compared with that of normal subjects (70).

The National Comorbidity Survey (20) reinforced the perception of social phobia as a major source of disability and suffering. It found a much higher lifetime prevalence for social phobia (13.3%) than the ECA. It showed that social phobia is negatively related to education and income and is significantly elevated among never-married individuals, students, persons who are neither working nor studying, and those who live with their parents. Approximately half of the persons with social phobia reported at least one outcome indicative of severity at some time in their lives (either significant role impairment, professional help seeking, or use of medication more than once); social phobia was also associated with low social support (71).

Subthreshold Social Phobia

Some studies suggest that the negative impact of social phobia on quality of life may be felt beyond the strict set of diagnostic criteria in DSM-III/DSM-III-R. Davidson and colleagues (72) examined the Duke University site’s ECA data to compare individuals with social phobia, subthreshold social phobia (i.e., phobic avoidance of public speaking and/or meeting strangers or eating in public not associated with significant functional interference), and nonphobic, healthy comparison subjects. Compared with nonphobic normal subjects, persons with noncomorbid subthreshold social phobia were more likely to be female and unmarried and to report less income and fewer years of education. Persons with uncomplicated subthreshold social phobia were also more likely to report poor grades and lack of a close friend—a measure of perceived social support. Davidson and colleagues (72) concluded that subthreshold social phobia, in terms of impairment, closely resembles social phobia diagnosed according to the DSM-III criteria, which is similar to Klerman and colleagues’ conclusions (44) with respect to infrequent panic attacks.

Some studies have investigated the possibility that the subtypes of social phobia may affect quality of life in different ways or degrees. Kessler and colleagues (73) used National Comorbidity Survey data to compare social phobia characterized by pure speaking fears and by other social fears. Overall, social phobia characterized by pure speaking fears was found to be less persistent, less impairing, and less highly comorbid than social phobia characterized by more generalized social fears. Thus, although even subthreshold social phobia may be associated with a reduced quality of life (72), these findings suggest that the most pervasive functional impairment and reduced quality of life is seen in persons who suffer from generalized social phobia (74).

Studies in Clinical Samples

Schneier and colleagues (40) examined the nature of impairment of functioning in 32 outpatients with social phobia by comparing their scores on two new rating scales—the Disability Profile and the Liebowitz Self-Rated Disability Scale—with those of 14 normal comparison subjects. The Disability Profile is a clinician-rated instrument with items assessing current (i.e., over the last 2 weeks) and most severe lifetime impairment due to emotional problems in eight domains. The Liebowitz Self-Rated Disability Scale is a patient-rated instrument with 11 items assessing current and most severe lifetime impairment due to emotional problems. More than half of all patients with social phobia reported at least moderate impairment at some time in their lives due to social anxiety and avoidance in areas of education, employment, family relationships, marriage or romantic relationships, friendships or social network, and other interests. A substantial minority reported at least moderate impairment in the areas of activities of daily living (such as shopping and personal care) and suicidal behavior or desire to live. On the Liebowitz scale, more than half of all patients reported at least moderate impairment in self-regulation of alcohol use at some time in their lives due to social phobia. Patients with social phobia were rated more impaired than normal comparison subjects on nearly all items on both measures. These findings on the Liebowitz Self-Rated Disability Scale must be considered preliminary, pending further validation of this instrument.

Wittchen and Beloch (75) measured quality of life and other indices of impairment in a group of 65 subjects with social phobia (with no significant comorbidity) and compared the results with those from a comparison group of individuals with herpes infection. The instruments employed included the Short-Form Health Survey and the Liebowitz Self-Rated Disability Scale. Compared to the matched comparison group, the group with social phobia had significantly lower scores (i.e., worse function) on most of the Short-Form Health Survey scales. Pronounced reductions in self-rated quality of life were found among the patients with social phobia in the domains of role limitation due to emotional problems, social functioning, general mental health, and vitality. Standardized summed scores for the mental health components of the Short-Form Health Survey showed that 23.1% of all subjects with social phobia were severely impaired and 24.6% were significantly impaired compared to only 4.5% of the comparison subjects. The Liebowitz Self-Rated Disability Scale showed that social phobia affected most areas of life but in particular education, career, and romantic relations.

Impact of Treatment on Quality of Life in Patients With Social Phobia

In a 12-week, double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled trial, Stein et al. (76) had patients with social phobia (91.3% with the generalized subtype of the disorder) treated with fluvoxamine, an SSRI. At the study’s endpoint, patients taking fluvoxamine (N=34) showed a significantly greater improvement in scores on the work functioning and family life and home functioning items of the Sheehan Disability Scale compared to placebo-treated patients (N=34).

Safren and colleagues (77) studied quality of life in a group of treatment-seeking persons with social phobia who underwent cognitive behavioral therapy for anxiety disorders in a university clinic. Subjects with comorbidities were not excluded. The instrument employed to measure quality of life was the Quality of Life Inventory (78), a 17-item scale that assesses a person’s satisfaction in a particular area of life that he or she deems important (such as health, relationships, and work). Patients with social phobia judged their overall quality of life as lower than that of a normative reference group. Quality of life was inversely associated with various measures of severity of social phobia (especially social interaction anxiety), functional impairment, and depression. Subjects with generalized social phobia had significantly lower scores on the Quality of Life Inventory than those with nongeneralized social phobia. Patients showed significant improvement in scores on the Quality of Life Inventory after completion of cognitive behavioral group therapy for social phobia. However, their posttreatment scores on the Quality of Life Inventory remained lower than those of the normative group.

These studies suggest that there may be merit to the continued inclusion of quality-of-life outcome measures in treatment studies of social phobia, although changes may turn out to be more subtle (and perhaps more difficult to measure) than those seen in panic disorder.

Quality of Life in Individuals With PTSD

Generations of military physicians described PTSD under a variety of rubrics: nostalgia (Civil War), shell shock (World War I), combat fatigue or combat exhaustion (World War II), or post-Vietnam syndrome (79, 80). When the diagnosis of PTSD was finally added to the official psychiatric nomenclature with the publication of the DSM-III in 1980, little was known about the role played by the disorder in civilian life. The misconception that PTSD could only result from either combat experiences or some unusually severe traumas in civilian life was incorporated into the DSM-III/DSM-III-R description of a stressor as being “outside the range of usual human experiences.” Recent appreciation of the role played by a wide range of traumas experienced in the community in the genesis of PTSD led to the suppression of this description in the DSM-IV, which in turn emphasizes the subjective experience of intense fear, helplessness, or horror resulting from a person’s exposure to real or threatened death or serious injury or to a threat to the physical integrity of self or others. This major conceptual change extended the scope of the PTSD construct well beyond its original limits. Readers must be aware that the cases defined according to the DSM-III/DSM-III-R criteria represent just part of the universe delineated by those criteria.

Studies in Epidemiologic Samples

Epidemiologic studies (81–83) found a lifetime prevalence for PTSD of 7.8% to 9.2%, with the rate in women two times higher than that in men. Zatzick and colleagues (84) undertook an archival analysis of data from the National Vietnam Veterans Readjustment Study to measure the impact of PTSD on functioning and quality of life. Six domains were examined: bed days in the past 2 weeks, role functioning, subjective well-being, self-reported physical health status, current physical functioning, and perpetration of violent interpersonal acts in the past year. The study subjects consisted of a nationally representative sample of 1,200 male Vietnam veterans. Poorer outcomes were significantly more common in subjects with PTSD than in subjects without PTSD in all domains except bed days in the past 2 weeks. Even after adjusting for demographic characteristics as well as for comorbid psychiatric and other medical disorders, subjects with PTSD continued to have a significantly higher risk of diminished well-being, fair or poor physical health, current unemployment, and physical limitations than did veterans without PTSD.

Zatzick and colleagues (85) also investigated the impact of PTSD on the quality of life of female veterans. A total of 432 female veterans of the Vietnam theater, most of whom were nurses, were assessed as part of the National Vietnam Veterans Readjustment Study. Functional impairment and diminished quality of life were assessed by responses to questions covering six domains: bed days in the past 3 months, role functioning, subjective well-being, self-reported physical health status, current physical functioning, and perpetration of violent interpersonal acts in the past year. PTSD was found to be associated with significantly elevated odds of poorer functioning in all domains, except perpetration of violence in the past year. After adjustment for demographic characteristics and medical and psychiatric comorbidities, PTSD remained associated with a statistically significant elevation of the odds of poorer functioning in three domains: role functioning, self-reported physical health status, and bed days in the past 3 months. When these results were compared with their findings in male Vietnam veterans (84), Zatzick and colleagues (85) found similar patterns of elevated odds across genders, suggesting that sex differences are minimal or absent in the extent to which PTSD is related to functional impairment.

Jordan and colleagues (86) interviewed Vietnam veterans and their spouses or co-resident partners as part of the National Vietnam Veterans Readjustment Study to assess family and marital adjustment, parenting problems, and the presence of violence. Veterans with PTSD were found to be much more likely to report marital, parental, and family adjustment problems than were veterans without PTSD. There was more violence in the families of veterans with PTSD than in the families of veterans without PTSD. The majority of the spouses and partners reported high levels of nonspecific distress, and the children of veterans with PTSD were more likely to have behavioral problems than were the children of veterans without PTSD. These data underscore that PTSD (and, by inference, other anxiety disorders, although this has been little studied) adversely affects the quality of life, not only of individuals with the disorder, but also of their families.

Stein and colleagues (87) studied the impact of full and “partial” PTSD (or subthreshold PTSD—i.e., having fewer than the required number of DSM-IV criterion C or criterion D symptoms) on the social functioning of a community sample. Persons with partial PTSD reported significantly more interference with work or education than did traumatized subjects without PTSD, but they reported significantly less interference than persons with the full disorder. Persons with full and partial PTSD reported comparable levels of interference with social and family functioning. The authors concluded that partial PTSD seems to carry a burden of disability that approaches, if not matches, that produced by full PTSD. These findings remain to be replicated by using more comprehensive and standardized measures of quality of life.

Studies in Clinical Samples and Impact of Treatment

There is presently a dearth of information about quality of life in patients with PTSD. But a study using the Short-Form Health Survey in 16 patients with PTSD who participated in a clinical trial suggests that quality of life is markedly compromised in this disorder (88). Furthermore, pilot data from this 12-week, double-blind, placebo-controlled study of the SSRI fluoxetine suggest that significant improvement in health-related quality of life can be obtained with pharmacologic treatment (88). These findings remain to be replicated in larger study groups and extended to other treatment modalities, but they are promising indeed.

Quality of Life in Individuals With OCD

Until 1980 obsessive-compulsive disorder was thought to be rare. The ECA study, however, found lifetime prevalences ranging from 1.94% to 3.29% (89), although a more recent study places the current prevalence rate in a somewhat lower range (90). Despite its well-known morbidity, few studies have attempted to measure the impact of OCD on quality of life.

Koran and colleagues (91) studied quality of life in 60 unmedicated patients with moderate-to-severe OCD using the Short-Form Health Survey and compared their scores with published norms for the general U.S. population and with patients with either depression or diabetes. Patients with OCD had higher median scores on all domains of physical health for quality of life (physical functioning, role limitation due to physical problems, and bodily pain) than patients with diabetes and depression and scored near the general population norm. In contrast, in all the domains of mental health (social functioning, role limitation due to emotional problems, and mental health), the OCD patients’ average scores were well below those of the general population. The diabetic patients’ median scores were similar to those of the depressed patients. The severity of OCD was negatively correlated with scores on social functioning (i.e., the more severe the disorder, the lower the scores). This single study, which remains to be replicated, portrayed OCD as a disorder with a marked negative impact on quality of life.

Quality of Life in Individuals With Generalized Anxiety Disorder

Probably none of the categories of anxiety disorder established in DSM-III has been more difficult to ratify than generalized anxiety disorder. After two waves of substantial revisions in the diagnostic criteria and almost 20 years of continuous research, the uncertainties concerning the nature, boundaries, and clinical implications of this nosologic entity remain as strong as ever. As Roy-Byrne and Katon (92) pointed out, “there continues to be considerable debate about whether generalized anxiety disorder is a freestanding primary disorder, a prodromal or residual phase of other disorders, a personality trait, or a comorbid condition that modifies the course, treatment response, and outcome of other diseases” (p. 34). There is increasing recognition that comorbidity is a fundamental feature in the nature and course of generalized anxiety disorder. Judd and colleagues (93) found that 80% of individuals with lifetime generalized anxiety disorder also had a comorbid mood disorder during their lifetime. This finding suggests that the ideal goal of studying “pure,” noncomorbid generalized anxiety disorder may be unattainable.

The ECA study used the DSM-III criteria for generalized anxiety disorder, which emphasize its status as a residual category, and found a reported lifetime prevalence of 4.1% to 6.6% (94). A total of 58% to 65% of the subjects who had generalized anxiety disorder also had at least one other DSM-III disorder. Persons with generalized anxiety disorder were more often unmarried or divorced. A significantly higher proportion of persons with generalized anxiety disorder than without had received disability benefits during their lifetimes. Even when employed, individuals with generalized anxiety disorder showed indirect evidence of impairment: a significantly higher proportion of them had annual incomes of less than $10,000 (1980 dollars).

The National Comorbidity Survey (95) used the DSM-III-R criteria for generalized anxiety disorder; these emphasize the presence of excessive and/or unrealistic worry, somatic symptoms, and a duration of at least 6 months. The hierarchical exclusion rules of the DSM-III, which preclude the diagnosis of generalized anxiety disorder if a patient meets the criteria for any other mental disorder, were replaced by a less restrictive rule that required only that the diagnosis of generalized anxiety disorder could not be assigned if it occurred during the course of a mood or psychotic disorder. Generalized anxiety disorder was found to be a relatively rare current disorder (current prevalence of 1.6%) but a more frequent lifetime disorder, affecting 5.1% of the U.S. population aged 15–54 years. The vast majority of persons with generalized anxiety disorder also had at least one other disorder (current morbidity, 66.3%; lifetime morbidity, 90.4%). The most frequent comorbid disorders were affective disorder and panic disorder. “Pure” lifetime generalized anxiety disorder was found to be rare, with a lifetime prevalence of 0.5%. Wittchen and colleagues (95) found that comorbidity was associated with a significantly greater likelihood of interference with daily activities (51.2% in comorbid generalized anxiety disorder; 28.1% in “pure” generalized anxiety disorder) and made it more difficult to assess the role played by noncomorbid generalized anxiety disorder.

Massion and colleagues (96) examined the effects of generalized anxiety disorder and panic disorder on the quality of life of a group of patients from the Harvard/Brown Anxiety Disorders Research Program using questions derived from the National Comorbidity Survey. Both groups showed impairment in role functioning and social life as well as low overall life satisfaction. Generalized anxiety disorder was associated with a reduction in overall emotional health. However, the finding that the vast majority of the patients with generalized anxiety disorder had at least one other anxiety disorder led the authors to affirm that “generalized anxiety disorder virtually never occurs in isolation” and made it difficult to assess the role played by noncomorbid generalized anxiety disorder. In summary, these limited data suggest that, although relatively rare, noncomorbid generalized anxiety disorder can be found in a substantial minority of individuals and is associated with important impairment in its own right.

Comparing the Relative Decrements in Quality of Life Attributable to Different Anxiety Disorders

Most, if not all, of the studies reviewed previously involve comparisons between the decrements in quality of life associated with a specific anxiety disorder and with physical disorders or major depression. These studies, part of the first generation of investigations on the impact of anxiety disorders on quality of life, were mainly comparing this impact against well-known “gold standards” of impairment and incapacity such as depression or hypertension. Recently, some studies have shifted the focus of their investigations toward comparing the decrements in quality of life attributable to different anxiety disorders and can be considered the forerunners of a new generation of studies on quality of life in patients with anxiety disorders.

Studies in Community Samples

Kessler and Frank (97) used National Comorbidity Survey data to examine relationships between DSM-III-R psychiatric disorders and work impairment in the U.S. labor force. Individuals with anxiety disorders, when compared to persons without them, showed statistically significantly higher rates of work impairment. Among individuals with anxiety disorders, those with panic disorder had the highest number of days on which their productivity was reduced (mean=4.87 days per month, SD=1.56), whereas those with social phobia had the lowest (mean=1.11 days per month, SD=0.47). Data for persons with generalized anxiety disorder and PTSD fell in the intermediate range (mean=3.11 days per month, SD=1.33; mean=2.76 days per month, SD=1.00, respectively).

Studies in Clinical Samples

Schonfeld and colleagues (51) employed the Short-Form Health Survey to investigate the degree to which untreated anxiety disorders and major depressive disorder, occurring either singly or in combination, reduced functioning and well-being among 637 primary-care patients. Trained lay interviewers administered the NIMH Diagnostic Interview Schedule to this group and identified 319 patients meeting the diagnostic criteria for one or more of six anxiety disorders (generalized anxiety disorder, PTSD, simple phobia, social phobia, panic disorder or agoraphobia, and OCD) and major depression. Of this group, 137 (43%) had a single disorder, and 182 (57%) had multiple disorders. Regression models were used to estimate the relative effects of these disorders on quality of life by comparing patients with anxiety disorders to patients without anxiety. Simple phobia and OCD scores were omitted from the analysis because they almost never occurred as single disorders. The estimated effect of each single disorder on all subscales for physical, social, and emotional functioning was substantial. The effects due to major depression were the most negative of any disorder, with reductions in score of more than 20 points (on a 100-point scale) below the predicted scores for the reference group with no disorders on six of eight subscales. Among the anxiety disorders, PTSD had significant negative effects across all functioning scales and was estimated to have the second most negative burden on five of the eight subscales of the Short-Form Health Survey; the main score reductions were observed in the subscales for role limitations (emotional) (42 points), role limitations (physical health) (29.2 points), and vitality (23.1 points). For panic disorder or agoraphobia, the largest score reductions were in the subscales for role limitations (physical health) (29.7 points) and bodily pain (20.1 points). The effects of generalized anxiety disorder were mostly felt in the subscales for role limitations (emotional) (28.2 points) and role limitations (physical health) (21.1 points). The role limitations (emotional) subscale showed the largest score reduction for social phobia (22 points). These findings highlight the value of examining specific domains of functioning across the anxiety disorders, because they appear to vary considerably.

Olfson and colleagues (98, 99) examined social and occupational disability associated with several DSM-IV mental disorders and groups of subthreshold psychiatric symptoms that did not meet the full criteria for a DSM-IV disorder (including depressive, generalized anxiety, panic, obsessive-compulsive, drug, and alcohol symptoms) in 1,001 adult primary-care outpatients in a large health maintenance organization. The assessment consisted of a structured diagnostic interview for DSM-IV given by telephone, the Sheehan Disability Scale, and three impairment items from the ECA study. After adjusting for the confounding effects of comorbid axis I disorders, other subthreshold symptoms, age, sex, race, marital status, and perceived physical health status, only subthreshold symptoms for depressive and panic disorder were found to be significantly correlated with impairment measures. Although depressive symptoms were significantly correlated with impairment in social, family, and work functioning, impairment associated with panic symptoms was restricted to loss of work and increased utilization of mental health services.

The construct of “illness intrusiveness” was described by Devins (28) as corresponding to “lifestyle disruptions, attributable to an illness and/or its treatment, that interfere with continued involvement in valued activities and interests” (p. 252). The Illness Intrusiveness Ratings Scale (29) is a multidimensional tool that examines 13 domains of functioning, each of which may be specifically affected by an illness or its treatment. Antony and colleagues (30) measured the extent to which anxiety disorders interfere with several domains of functioning by having individuals with panic disorder (N=35), social phobia (N=49), and OCD (N=51) complete the Illness Intrusiveness Ratings Scale. The three groups did not differ on total scores on the Illness Intrusiveness Ratings Scale, but significant differences in particular domains of functioning were observed. Patients with OCD reported more interference with respect to passive recreation (e.g., reading) than did patients with social phobia and more interference with respect to religious expression than did the two other groups. Patients with social phobia reported more impairment with respect to social relationships and self-expression or self-improvement than any other group. Average scores on the Illness Intrusiveness Ratings Scale for the three anxiety disorders were considerably higher than those found in other chronic illnesses. These findings are consistent with the well-known impairment of social life associated with social phobia and with the tendency of obsessions (many of them with religious content) to invade the consciousness and disrupt intentional activities.

Quality-of-Life Studies of Patients With Anxiety Disorders: Limitations and Prospects

Quality-of-life assessment has been instrumental in exposing the extent and seriousness of anxiety disorders. As summarized previously, both epidemiological and clinical studies clearly delineate the extensive reduction in quality of life associated with anxiety disorders and hint at possible differences between anxiety disorders. Significant degrees of impairment can also be found in individuals with subthreshold forms of anxiety disorders, particularly panic disorder. Preliminary evidence suggests that panic disorder and PTSD may exert a heavier toll on quality of life than other anxiety disorders. Effective pharmacological or psychotherapeutic treatments have been shown to improve the quality of life in patients with panic disorder and social phobia but have yet to be demonstrated for other anxiety disorders.

Several validated generic and specific instruments have been shown to adequately measure quality of life in patients with anxiety disorders, raising the issue of how to select the most adequate instrument for a given purpose. It has been suggested that future studies addressing quality of life should employ a combination of generic and specific instruments to maximize both sensitivity and generalizability (100). The Short-Form Health Survey is the most extensively tested generic measure and would constitute the natural candidate for an all-purpose instrument. The choice of the accompanying specific instrument should be determined by the specific goals of the study. An alternative approach would be the modular system proposed by Aaronson et al. (18): the Short-Form Health Survey would constitute the “generic core” to which one or several additional “specific” modules with 10–15 questions could be added. These modules would focus on domains of quality of life that are not captured by the Short-Form Health Survey but that are likely to be affected by the presence of anxiety disorders (such as sleep in PTSD) or by the treatment itself (such as the sexual function of patients medicated with SSRIs). A modular instrument, the Hepatitis Quality of Life Questionnaire (101), has been recently validated for the assessment of quality of life in patients with chronic hepatitis C; similar measures could be developed for anxiety disorders.

Progress in the field of the assessment of quality of life in anxiety disorders has not been homogeneous. Certain areas of knowledge are in need of further scientific investigation. First, although some disorders such as panic disorder have been reasonably well studied, others such as PTSD have been largely neglected. Second, there are disagreements between epidemiological and clinical findings in some areas that need to be clarified. The causes of this disagreement are open to debate and will require further study (102). Third, to our knowledge, only a handful of studies have attempted to compare the impact of different anxiety disorders on quality of life. Fourth, the original goal for which the concept of quality of life was first adopted in clinical research was to compare outcomes between different treatment modalities. However, we found only 11 studies—eight in panic disorder, two in social phobia, and a small pilot study on PTSD—that attempted to assess the impact of treatment on the quality of life in patients with anxiety disorders. This is surprising considering that unlike other areas of medical research, mental health has few physiological variables to employ as outcome measures and would likely benefit from an approach that has proved successful in oncology and cardiology. It is likely that therapies that are equivalent in terms of the reduction of symptoms may be qualitatively or quantitatively dissimilar with respect to effects on quality of life. Knowledge of these differences may lead to a more informed choice of treatment modality for a particular disorder and, perhaps, for individual patients. In this area, much additional research is needed.

Despite the growing number of studies undertaken during the past 15 years, the investigation of quality of life in individuals with anxiety disorders is still in its infancy. Nevertheless, the studies conducted to date almost uniformly portray a picture of anxiety disorders as illnesses that markedly compromise quality-of-life and psychosocial functioning in several functional domains. It is hoped that these findings will translate into a more accurate public (and health care policy) view of anxiety disorders as serious mental disorders worthy of further research and appropriate health care expenditures. Finally, outcome studies that incorporate quality-of-life indices will further inform us as to the efficacy of existing and new treatments to lessen the burden of illness attributable to these disorders.

|

Received June 18, 1999, revision received Nov. 5, 1999, accepted Dec. 10, 1999. From the Department of Psychiatry, University of California at San Diego. Address reprint requests to Dr. Stein, Department of Psychiatry, University of California at San Diego, 8950 Villa La Jolla Dr., Suite 2243, La Jolla, CA 92037; [email protected] (e-mail). Supported in part by NIMH grant MH-57835. The authors thank Leslie Wetherell for her review of the manuscript.

1. Regier DA, Boyd JH, Burke JD Jr, Rae DS, Myers JK, Kramer M, Robins LN, George LK, Karno M, Locke BZ: One-month prevalence of mental disorders in the United States: based on five Epidemiologic Catchment Area sites. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1988; 45:977–986Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

2. Pichot P: Nosological models in psychiatry. Br J Psychiatry 1994; 164:232–240Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

3. Klerman GL: Approaches to the phenomena of comorbidity, in Comorbidity of Mood and Anxiety Disorders. Edited by Maser JD, Cloninger CR. Washington, DC, American Psychiatric Press, 1990, pp 13–37Google Scholar

4. Klein DF, Fink M: Psychiatric reaction patterns to imipramine. Am J Psychiatry 1962; 119:432–438Link, Google Scholar

5. Feighner JP, Robins E, Guze SB, Woodruff RA Jr, Winokur G, Mu𮸠R: Diagnostic criteria for use in psychiatric research. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1972; 26:57–63Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

6. DuPont RL, Rice DP, Miller LS, Shiraki SS, Rowland CR, Harwood HJ: Economic costs of anxiety disorders. Anxiety 1996; 2:167–172Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

7. Spitzer WO, Dobson AJ, Hall J: Measuring the quality of life of cancer patients: a concise QL-index for use by physicians. J Chronic Dis 1981; 34:585–597Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

8. Croog SH, Levine S, Testa MA, Brown B, Bulpitt CJ, Jenkins CD, Klerman GL, Williams GH: The effects of antihypertensive therapy on the quality of life. N Engl J Med 1986; 314:1657–1664Google Scholar

9. Patrick DL, Erickson P: Health Status and Health Policy: Quality of Life in Health Care Evaluation and Resource Allocation. New York, Oxford University Press, 1993Google Scholar

10. Dimenas ES, Dahlof CG, Jern SC, Wiklund IK: Defining quality of life in medicine. Scand J Prim Health Care Suppl 1990; 1:7–10Medline, Google Scholar

11. Spilker B: Introduction, in Quality of Life and Pharmacoeconomics in Clinical Trials. Edited by Spilker B. Philadelphia, Lippincott-Raven, 1996, pp 1–10Google Scholar

12. Gill TM, Feinstein AR: A critical appraisal of the quality of quality-of-life measurements. JAMA 1994; 272:619–626Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

13. Palmore E, Luikart C: Health and social factors related to life satisfaction. J Health Soc Behav 1972, 13:68–80Google Scholar

14. Larson R: Thirty years of research on the subjective well-being of older Americans. J Gerontol 1978, 33:109–125Google Scholar

15. Gerin P, Dazord A, Boissel J, Chifflet R: Quality of life assessment in therapeutic trials: rationale for and presentation of a more appropriate instrument. Fundam Clin Pharmacol 1992; 6:263–276Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

16. Ware JE Jr: Standards for validating health measures: definition and content. J Chronic Dis 1987; 40:473–480Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

17. Patrick DL, Erickson P: What constitutes quality of life? concepts and dimensions. Clin Nutr 1988, 7:53–63Google Scholar

18. Aaronson NK, Bullinger M, Ahmedzai S: A modular approach to quality-of-life assessment in cancer clinical trials. Recent Results Cancer Res 1988; 111:231–249Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

19. Aaronson NK: Quality of life assessment in clinical trials: methodologic issues. Control Clin Trials 1989; 10(4 suppl):195S–208SGoogle Scholar

20. Kessler RC, McGonagle KA, Zhao S, Nelson CB, Hughes M, Eshleman S, Wittchen H-U, Kendler KS: Lifetime and 12-month prevalence of DSM-III-R psychiatric disorders in the United States: results from the National Comorbidity Survey. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1994; 51:8–19Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

21. Markowitz JS, Weissman MM, Ouellette R, Lish JD, Klerman GL: Quality of life in panic disorder. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1989; 46:984–992Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

22. Guyatt GH, Eagle DJ, Sackett B, Willan A, Griffith L, McIlroy W, Patterson CJ, Turpie I: Measuring quality of life in the frail elderly. J Clin Epidemiol 1993; 46:1433–1444Google Scholar

23. Ware JE Jr, Sherbourne CD: The MOS 36-Item Short-Form Health Survey (SF-36), I: conceptual framework and item selection. Med Care 1992; 30:473–483Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

24. McHorney CA, Ware JE Jr, Raczek AE: The MOS 36-Item Short-Form Health Survey (SF-36), II: psychometric and clinical tests of validity in measuring physical and mental health constructs. Med Care 1993; 31:247–263Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

25. McHorney CA, Ware JE Jr, Lu JF, Sherbourne CD: The MOS 36-item Short-Form Health Survey (SF-36), III: tests of data quality, scaling assumptions, and reliability across diverse patient groups. Med Care 1994; 32:40–66Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

26. Ware JE Jr, Kosinski M, Gandek B, Aaronson NK, Apolone G, Bech P, Brazier J, Bullinger M, Kaasa S, Leplège A, Prieto L, Sullivan M: The factor structure of the SF-36 Health Survey in 10 countries: results from the IQOLA Project. Med Care 1998; 51:1159–1165Google Scholar

27. Bullinger M, Alonso J, Apolone G, Lepl禥 A, Sullivan M, Wood-Dauphine S, Gandek B, Wagner A, Aaronson NK, Bech P, Fukuhara S, Kaasa S, Ware JE Jr: Translating health status questionnaires and evaluating their quality: the IQOLA Project approach. Med Care 1998; 51:913–923Google Scholar

28. Devins GM: Illness intrusiveness and the psychosocial impact of lifestyle disruptions in chronic life-threatening disease. Adv Ren Replace Ther 1994; 1:251–263Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

29. Devins GM, Binik YM, Hutchinson TA, Hollomby DJ, Barre PE, Guttmann RD: The emotional impact of end-stage renal disease: importance of patients’ perception of intrusiveness and control. Int J Psychiatry Med 1983–1984; 13:327–343Google Scholar

30. Antony MM, Roth D, Swinson RP, Huta V, Devins GM: Illness intrusiveness in individuals with panic disorder, obsessive-compulsive disorder, or social phobia. J Nerv Ment Dis 1998; 186:311–315Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

31. Devins GM, Mandin H, Hons RB, Burgess ED, Klassen J, Taub K, Schorr S, Letorneau PK, Buckle S: Illness intrusiveness and quality of life in end-stage renal disease: comparison and stability across treatment modalities. Health Psychol 1990, 9:117–142Google Scholar

32. Devins GM, Berman L, Shapiro CM: Impact of sleep apnea and other sleep disorders on marital relationships and adjustment (abstract). Sleep Res 1993, 22:550Google Scholar

33. Robb JC, Cooke RG, Devins GM, Trevor-Young L, Joffe RT: Quality of life and lifestyle in euthymic bipolar disorder. J Psychiatr Res 1997, 31:509–517Google Scholar

34. Endicott J, Nee J, Harrison W, Blumenthal R: Quality of Life Enjoyment and Satisfaction Questionnaire: a new measure. Psychopharmacol Bull 1993; 29:321–326Medline, Google Scholar

35. Weissman MM, Prusoff BA, Thompson WD, Harding PS, Myers JK: Social adjustment by self-report in a community sample and in psychiatric outpatients. J Nerv Ment Dis 1978; 166:317–326Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

36. Weissman MM, Bothwell S: Assessment of social adjustment by patient self-report. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1976, 33:1111–1115Google Scholar

37. Leon AC, Shear MK, Portera L, Klerman GL: Assessing impairment in patients with panic disorder: the Sheehan Disability Scale. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol 1992; 27:78–82Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

38. Sheehan DV: The Anxiety Disease. New York, Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1983Google Scholar

39. Leon AC, Olfson M, Portera L, Farber L, Sheehan DV: Assessing psychiatric impairment in primary care with the Sheehan Disability Scale. Int J Psychiatry Med 1997, 27:93–105Google Scholar

40. Schneier FR, Heckelman LR, Garfinkel R, Campeas R, Fallon BA, Gitow A, Street L, Del Bene D, Liebowitz MR: Functional impairment in social phobia. J Clin Psychiatry 1994; 55:322–331Medline, Google Scholar

41. Wells KB, Stewart A, Hays RD, Burnam MA, Rogers W, Daniels M, Berry S, Greenfield S, Ware J: The functioning and well-being of depressed patients: results from the Medical Outcomes Study. JAMA 1989; 262:914–919Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

42. Johnson J, Weissman MM, Klerman GL: Service utilization and social morbidity associated with depressive symptoms in the community. JAMA 1992; 267:1478–1483Google Scholar

43. Weissman MM: Panic disorder: impact on quality of life. J Clin Psychiatry 1991; 52(Feb suppl):6–8Google Scholar

44. Klerman GL, Weissman MM, Ouellette R, Johnson J, Greenwald S: Panic attacks in the community: social morbidity and health care utilization. JAMA 1991; 265:742–746Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

45. Gelder MG: Panic disorder: fact or fiction? Psychol Med 1989; 19:277–283Google Scholar

46. Eaton WW, Kessler RC, Wittchen HU, Magee WJ: Panic and panic disorder in the United States. Am J Psychiatry 1994; 151:413–420Link, Google Scholar

47. Katon W, Hollifield M, Chapman T, Mannuzza S, Ballenger J, Fyer A: Infrequent panic attacks: psychiatric comorbidity, personality characteristics and functional disability. J Psychiatr Res 1995; 29:121–131Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

48. McDowell I, Newell C: Measuring Health: A Guide for Rating Scales and Questionnaires, 2nd ed. New York, Oxford University Press, 1996Google Scholar

49. Sherbourne CD, Wells KB, Judd LL: Functioning and well-being of patients with panic disorder. Am J Psychiatry 1996; 153:213–218Link, Google Scholar

50. Hollifield M, Katon W, Skipper B, Chapman T, Ballenger JC, Mannuzza S, Fyer AJ: Panic disorder and quality of life: variables predictive of functional impairment. Am J Psychiatry 1997; 154:766–772Link, Google Scholar

51. Schonfeld WH, Verboncoeur CJ, Fifer SK, Lipschutz RC, Lubeck DP, Buesching DP: The functioning and well-being of patients with unrecognized anxiety disorders and major depressive disorder. J Affect Disord 1997; 43:105–119Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

52. Fyer AJ, Katon W, Hollifield M, Rassnick H, Mannuzza S, Chapman T, Ballenger JC: The DSM-IV panic disorder field trial: panic attack frequency and functional disability. Anxiety 1996; 2:157–166Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

53. Ettigi P, Meyerhoff AS, Chirban JT, Jacobs RJ, Wilson RR: The quality of life and employment in panic disorder. J Nerv Ment Dis 1997; 185:368–372Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

54. Candilis PJ, McLean RY, Otto MW, Manfro GG, Worthington JJ III, Penava SJ, Marzol PC, Pollack MH: Quality of life in patients with panic disorder. J Nerv Ment Dis 1999; 187:429–434Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

55. Rose MS, Koshman ML, Spreng S, Sheldon R: Statistical issues encountered in the comparison of health-related quality of life in diseased patients to published general population norms: problems and solutions. J Clin Epidemiol 1999; 52:405–412Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

56. Jacobs RJ, Davidson JR, Gupta S, Meyerhoff AS: The effects of clonazepam on quality of life and work productivity in panic disorder. Am J Manag Care 1997; 3:1187–1196Google Scholar

57. Mavissakalian MR, Perel JM, Talbott-Green M, Sloan C: Gauging the effectiveness of extended imipramine treatment for panic disorder with agoraphobia. Biol Psychiatry 1998; 43:848–854Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

58. Pohl RB, Wolkow RM, Clary CM: Sertraline in the treatment of panic disorder: a double-blind multicenter trial. Am J Psychiatry 1998; 155:1189–1195Google Scholar

59. Pollack MH, Otto MW, Worthington JJ, Manfro GG, Wolkow R: Sertraline in the treatment of panic disorder: a flexible-dose multicenter trial. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1998; 55:1010–1016Google Scholar

60. Hoehn-Saric R, McLeod DR, Hipsley PA: Effect of fluvoxamine on panic disorder. J Clin Psychopharmacol 1993; 13:321–326Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

61. Lecrubier Y, Judge R: Long-term evaluation of paroxetine, clomipramine and placebo in panic disorder. Collaborative Paroxetine Panic Study Investigators. Acta Psychiatr Scand 1997; 95:153–160Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

62. Michelson D, Lydiard RB, Pollack MH, Tamura RN, Hoog SL, Tepner R, Demitrack MA, Tollefson GD (Fluoxetine Panic Disorder Study Group): Outcome assessment and clinical improvement in panic disorder: evidence from a randomized controlled trial of fluoxetine and placebo. Am J Psychiatry 1998; 155:1570–1577Google Scholar

63. Telch MJ, Schmidt NB, Jaimez TL, Jacquin KM, Harrington PJ: Impact of cognitive-behavioral treatment on quality of life in panic disorder patients. J Consult Clin Psychol 1995; 63:823–830Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

64. Leon AC, Shear MK, Portera L, Klerman GL: The relationship of symptomatology to impairment in patients with panic disorder. J Psychiatr Res 1993; 27:361–367Crossref, Google Scholar

65. Pelissolo A, Lépine JP: Phobie sociale: perspectives historiques et conceptuèlles. Encéphale 1995; 21:15–24Google Scholar

66. Liebowitz MR, Gorman JM, Fyer AJ, Klein DF: Social phobia: review of a neglected anxiety disorder. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1985; 42:729–736Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

67. Amies PL, Gelder MG, Shaw PM: Social phobia: a comparative clinical study. Br J Psychiatry 1983; 142:174–179Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

68. Persson G, Nordlund CL: Agoraphobics and social phobics: differences in background factors, syndrome profiles and therapeutic response. Acta Psychiatr Scand 1985; 71:148–159Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

69. Solyom L, Ledwidge B, Solyom C: Delineating social phobia. Br J Psychiatry 1986; 149:464–470Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

70. Schneier FR, Johnson J, Hornig CD, Liebowitz MR, Weissman MM: Social phobia: comorbidity and morbidity in an epidemiologic sample. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1992; 49:282–288Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

71. Magee WJ, Eaton WW, Wittchen HU, McGonagle KA, Kessler RC: Agoraphobia, simple phobia, and social phobia in the National Comorbidity Survey. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1996; 53:159–168Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

72. Davidson JR, Hughes DC, George LK, Blazer DG: The boundary of social phobia: exploring the threshold. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1994; 51:975–983Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

73. Kessler RC, Stein MB, Berglund P: Social phobia subtypes in the National Comorbidity Survey. Am J Psychiatry 1998; 155:613–619Link, Google Scholar

74. Stein MB, Chavira DA: Subtypes of social phobia and comorbidity with depression and other anxiety disorders. J Affect Disord 1998; 50(suppl 1):S11–S16Google Scholar

75. Wittchen HU, Beloch E: The impact of social phobia on quality of life. Int Clin Psychopharmacol 1996; 11(suppl 3):15–23Google Scholar

76. Stein MB, Fyer AJ, Davidson JRT, Pollack MH, Wiita B: Fluvoxamine treatment of social phobia (social anxiety disorder): a double-blind, placebo-controlled study. Am J Psychiatry 1999; 156:756–760Abstract, Google Scholar

77. Safren SA, Heimberg RG, Brown EJ, Holle C: Quality of life in social phobia. Depress Anxiety 1996–1997; 4:126–133Google Scholar

78. Frisch MB, Cornell J, Villanueva M, Retzlaff PJ: Clinical validation of the Quality of Life Inventory: a measure of life satisfaction for use in treatment planning and outcome assessment. Psychol Assessment 1992; 4:92–101Crossref, Google Scholar

79. Helzer JE, Robins LN, McEvoy L: Post-traumatic stress disorder in the general population: findings of the Epidemiologic Catchment Area survey. N Engl J Med 1987; 317:1630–1634Google Scholar

80. Jordan BK, Schlenger WE, Hough RL, Kulka RA, Weiss DS, Fairbank JA, Marmar CR: Lifetime and current prevalence of specific psychiatric disorders among Vietnam veterans and controls. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1991; 48:207–215Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

81. Breslau N, Davis GC, Andreski P, Peterson E: Traumatic events and posttraumatic stress disorder in an urban population of young adults. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1991; 48:216–222Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

82. Kessler RC, Sonnega A, Bromet E, Hughes M, Nelson CB: Posttraumatic stress disorder in the National Comorbidity Survey. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1995; 52:1048–1060Google Scholar

83. Breslau N, Kessler RC, Chilcoat HD, Schultz LR, Davis GC, Andreski P: Trauma and posttraumatic stress disorder in the community: the 1996 Detroit Area Survey of Trauma. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1998; 55:626–632Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

84. Zatzick DF, Marmar CR, Weiss DS, Browner WS, Metzler TJ, Golding JM, Stewart A, Schlenger WE, Wells KB: Posttraumatic stress disorder and functioning and quality of life outcomes in a nationally representative sample of male Vietnam veterans. Am J Psychiatry 1997; 154:1690–1695Google Scholar

85. Zatzick DF, Weiss DS, Marmar CR, Metzler TJ, Wells KB, Golding JM, Stewart A, Schlenger WE, Browner WS: Posttraumatic stress disorder and functioning and quality of life outcomes in female Vietnam veterans. Mil Med 1997; 162:661–665Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

86. Jordan BK, Marmar CR, Fairbank JA, Schlenger WE, Kulka RA, Hough RL, Weiss DS: Problems with families of male Vietnam veterans with posttraumatic stress disorder. J Consult Clin Psychol 1992; 60:916–926Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

87. Stein MB, Walker JR, Hazen AL, Forde DR: Full and partial posttraumatic stress disorder: findings from a community survey. Am J Psychiatry 1997; 154:1114–1119Google Scholar

88. Malik ML, Connor KM, Sutherland SM, Smith RD, Davison RM, Davidson JR: Quality of life and posttraumatic stress disorder: a pilot study assessing changes in SF-36 scores before and after treatment in a placebo-controlled trial of fluoxetine. J Trauma Stress 1999; 12:387–393Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

89. Rasmussen SA, Eisen JL: Epidemiology of obsessive-compulsive disorder. J Clin Psychiatry 1990; 51(suppl 2):10–13Google Scholar

90. Stein MB, Forde DR, Anderson G, Walker JR: Obsessive-compulsive disorder in the community: an epidemiologic survey with clinical reappraisal. Am J Psychiatry 1997; 154:1120–1126Google Scholar

91. Koran LM, Thienemann ML, Davenport R: Quality of life for patients with obsessive-compulsive disorder. Am J Psychiatry 1996; 153:783–788Link, Google Scholar

92. Roy-Byrne PP, Katon W: Generalized anxiety disorder in primary care: the precursor/modifier pathway to increased health care utilization. J Clin Psychiatry 1997; 58(suppl 3):34–38Google Scholar

93. Judd LL, Kessler RC, Paulus MP, Zeller PV, Wittchen H-U, Kunovac JL: Comorbidity as a fundamental feature of generalized anxiety disorders: results from the National Comorbidity Study (NCS). Acta Psychiatr Scand Suppl 1998; 393:6–11Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

94. Blazer DG, Hughes D, George LK, Swartz M, Boyer R: Generalized anxiety disorder, in Psychiatric Disorders in America: The Epidemiologic Catchment Area Study. Edited by Robins LN, Regier DA. New York, Free Press; 1991, pp 180–203Google Scholar

95. Wittchen H-U, Zhao S, Kessler RC, Eaton WW: DSM-III-R generalized anxiety disorder in the National Comorbidity Study. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1994; 51:355–364Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

96. Massion AO, Warshaw MG, Keller MB: Quality of life and psychiatric morbidity in panic disorder and generalized anxiety disorder. Am J Psychiatry 1993; 150:600–607Link, Google Scholar

97. Kessler RC, Frank RG: The impact of psychiatric disorders on work loss days. Psychol Med 1997; 27:861–873Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

98. Olfson M, Broadhead WE, Weissman MM, Leon AC, Farber L, Hoven C, Kathol RG: Subthreshold psychiatric symptoms in a primary care group practice. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1996; 53:880–886Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

99. Olfson M, Fireman B, Weissman MM, Leon AC, Sheehan DV, Kathol RG, Hoven C, Farber L: Mental disorders and disability among patients in a primary care group practice. Am J Psychiatry 1997; 154:1734–1740Google Scholar

100. Eisen GM, Locke GR III, Provenzale D: Health-related quality of life: a primer for gastroenterologists. Am J Gastroenterol 1999; 94:2017–2021Google Scholar

101. Bayliss MS, Gandek B, Bungay KM, Sugano D, Hsu MA, Ware JE Jr: A questionnaire to assess the generic and disease-specific health outcomes of patients with chronic hepatitis C. Qual Life Res 1998; 7:39–55Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

102. Regier DA, Kaelber CT, Rae DS, Farmer ME, Knauper B, Kessler R, Norquist GS: Limitations of diagnostic criteria and assessment instruments for mental disorders: implications for research and policy. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1998; 55:109–115Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar