Growth of the Literature on the Topic of Personality Disorders

Abstract

OBJECTIVE: The authors assessed the growth of the literature on the topic of personality disorders before and after publication of DSM-III. METHOD: A MEDLINE search was conducted for journal articles concerning the personality disorders that were published from 1966 to 1995. RESULTS: Contrary to the authors’ prediction, the growth of this literature was slower after the publication of DSM-III in 1980 than it was before that date. Other areas of psychopathology, such as Alzheimer’s disease and posttraumatic stress disorder, have literatures whose growth rates since 1980 have exceeded their growth rates before publication of DSM-III. CONCLUSIONS: Over one-half of the individual personality disorders (e.g., histrionic and passive-aggressive) have either very small literatures or literatures with negative growth rates. Only three personality disorders (i.e., antisocial, borderline, and schizotypal) have modestly growing literatures.

This study examines the growth of journal literature on the topic of personality disorders. In an important book about the sociology of science, Price (1) showed that the literature of science has grown exponentially over the last three centuries. More specifically, the scientific literature doubles once every 15 to 20 years. Menard (2) followed up Price’s finding by showing that different subfields of science grow at different rates. These different growth rates have important practical correlates for the various areas of science. “Hot” subfields represent topics for which there is a substantial amount of available funding; new researchers are attracted to these subfields, and these topics often represent the cutting edge of technological advances. In slowly growing subfields, numbers of researchers are relatively fixed, new researchers find it difficult to become established, and funding for future research is unlikely.

Research interest in the personality disorders is a relatively new phenomenon compared to the extensive research literatures on the topics of schizophrenia, depression, and Alzheimer’s disease. Shea (3) suggested that an important impetus to the growth of the research literature on the topic of personality disorders was the placement of these disorders on axis II in DSM-III. Tyrer (4) used this perceived growth in literature as an argument for keeping the personality disorders on a separate diagnostic axis. The central hypothesis examined in this study is that research involving personality disorders grew more rapidly after the publication of DSM-III in 1980 than before that date.

METHOD

A comprehensive literature review from 1966 to 1995 was conducted by means of the MEDLINE database. MEDLINE was chosen because it is the largest index of medical and psychological journals. Annual data were gathered regarding the number of journal articles published per individual personality disorder, the total number of articles in MEDLINE, and the total number of articles concerning personality disorders. The total for the articles concerning personality disorders was the sum of the data for each individual personality disorder. This reason for this definition was that the generic heading “personality disorders” in MEDLINE includes part of the substance abuse literature, articles about impulse-control problems, and some literature regarding sexual deviation. As a basis for comparison, MEDLINE searches were also conducted for the number of journal articles regarding schizophrenia, Alzheimer’s disease, and posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD).

These data were gathered by means of the 1996 and 1997 SilverPlatter International NV, WebSpirs version 3.1 software. They were later reexamined by means of the 1998 Gateway Ovid Technologies software. No significant variations in the numbers of articles per year were found as a function of the platforms used to access MEDLINE.

RESULTS

The English-language literature for medicine during the last third of the twentieth century has been growing at a stable rate. In 1966, there were approximately 175,000 articles in the medical literature; by 1995, this number had more than doubled to slightly fewer than 400,000 articles. The growth of the medical literature appears linear. This linearity occurs because, even though scientific literatures grow exponentially, a 30-year segment is a relatively small piece of a three-century-old growth curve (1). Small segments of curves often appear as straight lines.

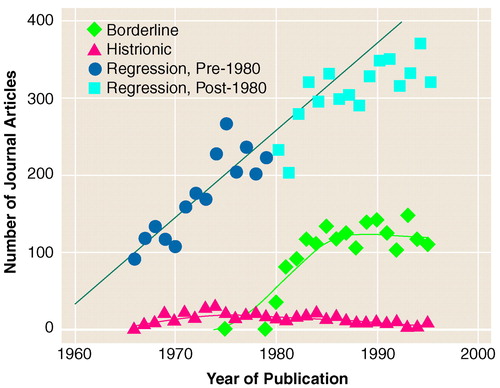

Figure 1 plots the literature regarding personality disorders as indexed in MEDLINE during the same 30-year period. The literature regarding personality disorders has grown from about 100 journal articles in 1966 to over 300 articles by the early 1990s. The straight line shown in figure 1 is the best-fitting linear regression model on the basis of the journal literature on personality disorders from 1966 to 1980. Had the inclusion of personality disorders on axis II in DSM-III led to an increased interest in this set of disorders, the data points after 1980 would have been above this straight line. However, the opposite occurred. The number of journal articles regarding personality disorders published after 1980 was smaller than expected on the basis of pre-1980 data.

An analysis of the data for PTSD and Alzheimer’s disease showed a striking contrast. The literature on Alzheimer’s disease has virtually exploded in the last two decades. This literature has expanded from about 100 articles in 1980 to about 2,000 articles in 1997. The literature on PTSD has shown almost 10-fold growth in the same period. The absolute size of the literature on schizophrenia has been large (about 800 articles in 1966), but its growth has been distinctly slower than that of Alzheimer’s disease or PTSD. However, when compared to its pre-DSM-III regression line, the literature on schizophrenia during the 1990s has exceeded the growth rate expected before DSM-III was published. Thus, the literatures for schizophrenia, Alzheimer’s disease, and PTSD have exceeded pre-DSM-III growth rates, but the literature on personality disorders, despite the disorders’ placement on axis II, has not.

Figure 1 also displays changes in the literatures for two specific personality disorders: borderline and histrionic. The literature on borderline personality disorder showed a striking rate of growth after DSM-III was published, quickly reaching more than 100 articles per year after 1982. In contrast, the growth of the literature on histrionic personality disorder has been distinctly smaller in size and has been consistently declining since the mid-1970s.

There were five disorders (dependent, narcissistic, obsessive-compulsive, paranoid, and passive-aggressive) that had very small literatures, averaging fewer than 10 articles per year. There were six disorders (dependent, histrionic, obsessive-compulsive, paranoid, passive-aggressive, and schizoid) whose literature growth was either flat (with no appreciable slope) or negative (with a downward slope). The only personality disorder whose literature is clearly alive and growing is that of borderline personality disorder. Antisocial personality disorder has a large literature but has shown relatively stagnant growth over the last three decades (with some change in the 1990s). Finally, the literature on schizotypal personality disorder has been growing but has not topped 100 articles per year.

DISCUSSION

Our first conclusion is that the literature on personality disorders has been growing steadily over the last three decades and appears to double once every 20–25 years (figure 1). This rate of growth is similar to that of the general medical literature, which has doubled about once every 23 years.

Our second finding is that the growth rate of the literature regarding personality disorders did not increase after the placement of these disorders on axis II in DSM-III. In fact, the journal literature on personality disorders actually appeared to grow more slowly than what might have been expected before publication of DSM-III.

Third, many of the individual personality disorders had literatures that had either very small (i.e., “dead”) or negative growth functions (i.e., “dying”). Only three personality disorders (antisocial, borderline, and schizotypal) had literatures that were alive and well. The size of the literature for a personality disorder is not correlated with the validity of the disorder. However, disorders with literature growth that is dead or dying are not succeeding at accumulating new empirical knowledge, nor are they likely to be stimulating substantial clinical interest.

Received March 15, 1999; revision received Aug. 13, 1999; accepted Sept. 6, 1999. Address reprint requests to Dr. Blashfield, Department of Psychology, Auburn University, 226 Thach Hall, Auburn University, AL 36849; [email protected] (e-mail).

FIGURE 1. Growth of the Journal Literature Regarding Personality Disorders, 1966–1995, as Indexed in MEDLINE

1. Price DDS: Big Science, Little Science. New Haven, Conn, Yale University Press, 1963Google Scholar

2. Menard HW: Science: Growth and Change. Cambridge, Mass, Harvard University Press, 1971Google Scholar

3. Shea MT: Interrelationships among categories of personality disorders, in The DSM-IV Personality Disorders: Diagnosis and Treatment of Mental Disorders. Edited by Livesley WJ. New York, Guilford, 1995, pp 397–406Google Scholar

4. Tyrer P: Are personality disorders well classified in DSM-IV? Ibid, pp 29–42Google Scholar