Screening for Depression in Mothers Bringing Their Offspring for Evaluation or Treatment of Depression

Abstract

OBJECTIVE: Numerous studies have shown that the highest risk for first onset of depression occurs in women of childbearing years and that there is a strong association between lifetime rates of depressive disorders in mothers and their offspring. This association is found regardless of whether the mother or child is the targeted patient. However, little is known about rates of current depression in mothers who bring their offspring to outpatient clinics for evaluation and/or treatment of depression. This information might be useful in developing intervention strategies. METHOD: One hundred seventeen mothers bringing their offspring for evaluation or treatment for depression were screened with the Patient Problem Questionnaire to determine current symptoms of depression, anxiety disorders, and substance abuse as well as current psychiatric treatment. RESULTS: Thirty-six (31%) of the mothers screened positive on the Patient Problem Questionnaire for a current psychiatric disorder. Sixteen (14%) screened positive for current major depression, 20 (17%) for panic disorder, 20 (17%) for generalized anxiety disorder, two (2%) for alcohol abuse, and one (1%) for drug abuse. In addition, 50 (43%) of the mothers had psychiatric symptoms that did not meet the diagnostic threshold for any of the above disorders. Twenty-six (22%) of mothers expressed suicidal ideation or intent. Only five (31%) of the 16 mothers diagnosed with major depression were currently receiving any psychiatric treatment. CONCLUSIONS: A substantial number of mothers bringing their offspring for evaluation or treatment of depression were themselves currently depressed and untreated. The treatment of depressed mothers may help both the mothers and their depressed offspring.

Epidemiologic studies have shown that the highest risk for first onset of major depression occurs in women of childbearing years, ages 18–44 (1–4). These patterns are found in epidemiologic studies across diverse cultures (5). It has also been shown that, compared with the offspring of control parents, offspring of depressed parents (top-down sampling) are at greater risk (two- to threefold) for major depressive disorder with an early age at onset as well as persistent behavioral, medical, and social problems (6–9). Finally, family studies of the parents and siblings of depressed children and adolescents (i.e., bottom-up sampling from the depressed children) also found a twofold greater risk of depression in their first-degree relatives, especially their mothers (10–14).

The high-risk and family studies focus on lifetime rates of depression in both mothers and offspring and, therefore, provide important information about the risk of depression between generations. To establish optimal points of intervention (such as, when mothers are seeking treatment for offspring), it is necessary to obtain additional information about periods of current risk for depression in mothers and their offspring.

In this article, we determine the current rates of depression, anxiety, and substance abuse in mothers seeking psychiatric evaluation and/or treatment for depression in their offspring. We decided to screen our subjects at this point because family studies of depression suggested that the rate would be high in the mothers of depressed children. Also, if diagnosed, the mothers might be more amenable to accept treatment in the context of their offspring’s treatment. The present screening study is the first phase of a treatment intervention study of depressed mothers of depressed offspring. Our overall goal is to determine whether treating maternal depression will improve the treatment response and general welfare of offspring, as well as to help break the cycle of depressive disorders between generations.

In this article we report findings from the first phase of the study on the prevalence of psychopathology and current treatment status in mothers. We chose mothers and not fathers because of the higher rate of depression in women and the fact that fathers are rarely the parent bringing offspring to treatment. To our knowledge, there are no published data on the rates of current depression in parents bringing their offspring for treatment.

METHOD

Mothers were ascertained through their offspring’s evaluation or treatment for depression at one of three clinics at Columbia Presbyterian Medical Center: the Child Anxiety and Depression Clinic, the Clinical Core of Child Psychiatry Mental Health Clinical Research Center, and the Ruane Diagnostic Unit, a pediatric psychiatry clinic for the evaluation of depression and anxiety disorders. Offspring had to be between the ages of 6 and 18 and initially identified through case records as having symptoms or a diagnosis of unipolar, nonpsychotic depression by clinic staff (child psychiatrists, doctoral-level child psychologists, and clinical child social workers). No other exclusionary criteria in offspring, including comorbid conditions, were applied. In addition, the mothers of these offspring had to be the child’s biological parent, older than age 18, and fluent in English or Spanish. Based on these study inclusion criteria, 120 mothers were eligible to participate during the study period (Sept. 1, 1997, to Sept. 30, 1998); 117 (98%) of these mothers agreed to participate in the study. All subjects provided written informed consent after they were given a complete description of the study.

The mothers’ screening diagnosis of major depression, anxiety, or substance abuse was determined by using a modified version of the PRIME-MD Patient Problem Questionnaire (15). The Patient Problem Questionnaire is the self-report version of the Primary Care Evaluation of Mental Disorders (16), which was designed by Spitzer et al. for the screening of psychiatric disorders in an adult primary practice setting. It is available in English and Spanish and can be used as an interview if the patient cannot read the questionnaire (15). The Patient Problem Questionnaire was used as an interview with 76 (65%) of the mothers and as a self-report with 41 (35%). Forty-two (36%) of the mothers completed the Patient Problem Questionnaire in English, and 75 (64%) did so in Spanish.

The Patient Problem Questionnaire assesses current symptoms of eight disorders. We selected four psychiatric diagnoses for the present study: major depressive disorder, panic disorder, generalized anxiety disorder, and alcohol abuse. We added a drug abuse diagnosis that was fashioned directly from the alcohol abuse diagnosis. The time frame employed in making diagnostic ratings varied. Depression was rated for the last 2 weeks, anxiety disorders for the last 4 weeks, and alcohol abuse/dependence for the last 6 months. The Patient Problem Questionnaire must be considered a screen because it does not include all of the DSM-IV criteria for every disorder assessed. However, it includes all symptom criteria of DSM-IV major depression, including the modifier of “nearly every day.” The Patient Problem Questionnaire does not assess for how much of the day the symptom is present or the B, C, D, and E criteria of a major depressive episode.

Diagnostic criteria were based on Spitzer’s PRIME-MD Patient Problem Questionnaire (15). All disorders, with the exception of alcohol and drug abuse, were diagnosed as screened positive or subsyndromal. Alcohol and drug abuse were diagnosed only as screened positive. A diagnosis of screened positive for major depression required five of the nine depression symptoms present nearly every day over the past 2 weeks; one of the five symptoms must have been either depressed mood or anhedonia. Subsyndromal depression required one of the following: two to four symptoms present nearly every day over the past 2 weeks, two to nine symptoms rated present more than half the days over the last 2 weeks, or three to nine symptoms rated as present for several days over the past 2 weeks.

To determine the validity of the Patient Problem Questionnaire, Spitzer et al. (unpublished) studied 537 primary care patients whose psychiatric diagnoses based on the Patient Problem Questionnaire administered as a self-report instrument were compared with the assessments of mental health professionals using a hybrid of the PRIME-MD instrument and the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV (16) administered over the telephone. Kappas for the agreement between Patient Problem Questionnaire diagnosis and the diagnosis of mental health professionals ranged from 0.54 to 0.70, with a median of 0.66. The kappa for any diagnosis was 0.66, and the kappa for both any mood disorder and for major depressive disorder was 0.59. Any anxiety disorder had a kappa of 0.61, and panic disorder had a kappa of 0.70. The kappa for alcohol abuse was 0.66. These kappas are similar to those reported by Spitzer et al. (unpublished) in a separate study of 431 primary care patients comparing PRIME-MD ratings administered by primary care physicians with those given by mental health professionals (range=0.55–0.73, median=0.61).

In addition to screening with the Patient Problem Questionnaire, we assessed the mothers’ perception of their overall current emotional health (rated on a 4-point scale) and their mental health treatment history.

Descriptive data are presented with regard to rates of subject characteristics and diagnoses. Comparisons between subgroups, based on current treatment or diagnostic status and method of Patient Problem Questionnaire administration (i.e., interviewer administered versus self-report), were performed by chi-square analyses.

RESULTS

One hundred seventeen (98%) of the 120 eligible mothers participated in the present study. Their mean age was 39.8 years (range=27–56, SD=6.6). Table 1 presents data on ethnicity, language, marital and economic status, and education.

The offspring being brought for evaluation and/or treatment of depression had a mean age of 13.2 years (SD=3.0); 64 (55%) were girls. Diagnoses of the offspring, based on clinician rating, were major depressive disorder (N=69 [59%]), dysthymic disorder (N=18 [15%]), depressive disorder not otherwise specified (N=20 [17%]), and adjustment disorder with depressed mood (10 [9%]).

No significant demographic differences between mothers were found when they were grouped according to whether they had a current diagnosis or were currently in treatment. Mothers who completed the Patient Problem Questionnaire as an interview rather than self-report were more likely to be Spanish speaking (N=55 of 76 [72%]) (χ2=6.44, df=1, p<0.01) and on public assistance (N=46 of 70 [66%]) (χ2=6.20, df=1, p<0.01).

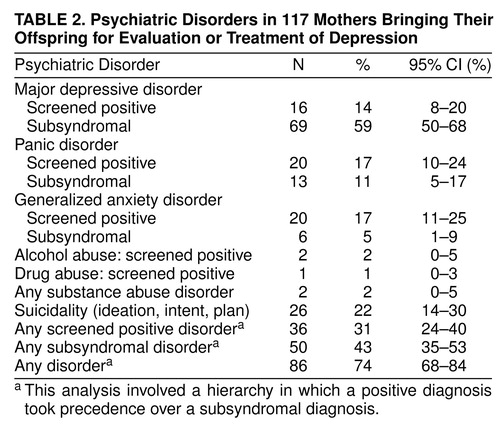

We found that 31% of the mothers screened positive for a current psychiatric disorder and 43% for a current subsyndromal disorder (table 2). No differences in rates of diagnosis were found on the basis of method (self-report or interview) of Patient Problem Questionnaire administration. Fifty-six (48%) of the mothers rated their overall emotional health as very good to excellent, 41 (35%) as good, and 20 (17%) as fair to poor.

Fourteen percent of the mothers screened positive for major depression, and 59% met criteria for a subsyndromal depression. Nearly one-fourth of the mothers reported some suicidality in response to the following question: “Over the last 2 weeks, how often have you been bothered by…thoughts that you would be better off dead or hurting yourself in some way?” (table 2).

Seventeen percent of the mothers screened positive for panic disorder, and 11% reported subsyndromal levels. Seventeen percent screened positive for generalized anxiety disorder, and 5% reported subsyndromal levels. All mothers who received an anxiety disorder diagnosis, with the exception of one mother with subsyndromal generalized anxiety disorder, had comorbid depression. Only two mothers screened positive for alcohol or drug abuse (one for alcohol abuse alone and one for both alcohol and drug abuse); both of these women had comorbid depression.

Not shown in table 2, 20 (17%) of the mothers reported that they were currently in treatment. Five (31%) of the 16 mothers who screened positive for major depression were currently in treatment. Fourteen (20%) of the 69 mothers who had a subsyndromal depression were currently in treatment. The only mother who received a diagnosis other than depression (i.e., subsyndromal generalized anxiety disorder) was not currently receiving psychiatric treatment. One (3%) of the 31 mothers who screened negative for all Patient Problem Questionnaire diagnoses was currently in treatment.

The 19 depressed mothers who were receiving current treatment saw a variety of mental health professionals, usually psychiatrists (N=16 [84%]) and psychologists (N=11 [58%]). Treatment was perceived as moderately to extremely helpful by 18 (95%) of the mothers who reported receiving it. Information was not obtained about treatment quality, duration, or compliance.

Eighteen (95%) of the 19 mothers who were currently in treatment received antidepressant medication (median number of weeks=88, range=13–531 weeks). All 18 of the women had received antidepressant medication in the past year and were still receiving it at the time of Patient Problem Questionnaire assessment. Antidepressant medication was perceived as being moderately to extremely helpful by 16 (89%) of the 18 women who reported receiving it. We have no information, however, about medication dose or compliance.

Fourteen (17%) of the 85 depressed mothers (74% of those in current treatment) had also tried a variety of alternative treatments for depression in the previous year, including St. John’s wort, exercise, vitamins, diet, caffeine, and other herbal remedies. Alternative treatments were also perceived as helpful by 12 (86%) of the women who tried them.

DISCUSSION

To our knowledge, this is the first published study to document the presence of current depressive symptoms in mothers bringing their offspring for evaluation or treatment of depression. A high percentage of the mothers were themselves depressed and untreated. These findings are consistent with community-based studies that reported a high rate of depression in young women of childbearing age (1, 3, 5) and with studies of the parents of depressed children (10–14). Finally, the present study is also consistent with studies showing a significant association between the timing of maternal and offspring depressive episodes: children who have a depressive episode may do so in close proximity to maternal episodes of depression, although one does not clearly follow the other (17).

The rate of current suicidality (ideation or intent) in the mothers who were depressed (22%) is high compared with the rate of suicidal ideation reported in a recent study (18) that found a lifetime prevalence of 13%–18% for women in the United States. This comparison should be made cautiously because current rates of suicidality were not available in the latter samples. Given the frequent comorbidity between depressive and anxiety disorders, the rates of panic and generalized anxiety reported in our subjects are not surprising. The low rate of reported substance abuse (2%) in the present study is consistent with studies of patients coming to primary care clinics. For example, the primary care studies of Spitzer’s group (19, 20), which used a similar instrument, reported that the prevalence of alcohol abuse and dependence was 5% overall, 10% for males, and 2% for females. Our finding is also consistent with the report by Weissman et al. (21) of low rates of reported alcohol abuse in their study of primary care patients. Likewise, women in the Epidemiologic Catchment Area (ECA) study (22) reported current (6-month) prevalence rates of alcohol abuse and dependence ranging from 1.0% to 1.9% across all age groups and from 0.5% to 2.8% in the 25–65-year-old range. It is also possible that mothers in our study may have been reluctant to report substance use because of concerns regarding the appearance of poor mothering and potential removal of offspring from their care.

Only 31% of the mothers diagnosed with major depression were currently receiving treatment. This finding is consistent with reports from both the ECA study (23, 24) and the National Comorbidity Survey (25), which showed that approximately one-third of depressed people in the community receive treatment.

It is possible that maternal disorders were overdiagnosed because not all diagnostic criteria are assessed by the Patient Problem Questionnaire. This is especially relevant in the case of major depression, for which the criterion of impaired functioning is integral to making a diagnosis and is not assessed by the Patient Problem Questionnaire. Therefore, we may have overestimated the rates of major depression. However, it should be noted that the rate of suicidality, which is unlikely to be overestimated, was even higher than the rate of major depression. Overdiagnosis has implications for rates of treatment: if major depression is overestimated in the present study, then the actual rate of treatment associated with it would be underestimated.

The present study has several limitations. It is generalizable only to a self-selected group of mothers who were predominantly urban, with low socioeconomic status, Hispanic, and bringing their offspring for evaluation and/or treatment of depression. Our findings cannot be generalized to other groups of mothers or to fathers. We are unable to make a definitive statement regarding treatment needs because we do not have information on the degree of functional impairment experienced by the mothers in our study. Clinical diagnosis of depression in the offspring was made by a variety of clinicians whose reliability is unknown. Finally, we did not systematically collect information on how offspring were referred to the three Columbia Presbyterian Medical Center clinics. In general, referrals were primarily from schools, other pediatric psychiatry clinics, and self-referrals.

Given the strong association between major depressive disorder in mothers and their offspring as well as the impairment in offspring of depressed parents, our findings suggest that it would be of value for mothers who bring their offspring for treatment of depression to be assessed for depression themselves. These mothers might be suitable targets for intervention. The majority of mothers who were currently receiving treatment for depression reported that they found their treatment helpful regardless of type of therapist or treatment modality, further suggesting that this group might be receptive to treatment if it were made available. A pilot intervention study with depressed mothers bringing depressed offspring for treatment is underway.

Presented as a poster at the annual meeting of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, Anaheim, Calif., Oct. 27–Nov. 1, 1998. Received Jan. 15, 1999; revision received July 19, 1999; accepted Aug. 24, 1999From the Divisions of Clinical and Genetic Epidemiology and Child Psychiatry, New York State Psychiatric Institute, Columbia University College of Physicians and Surgeons. Address reprint requests to Dr. Ferro, Division of Clinical and Genetic Epidemiology, New York State Psychiatric Institute, Columbia University, 1051 Riverside Dr., Unit 24, New York, NY 10032; [email protected] (e-mail). Supported by NIMH grants MH-16434 and MH-43878 and by the Samuel Priest Rose Research Award. The authors thank Talia Zaider, B.A., Mark Davies, M.P.H., Bob Falanga, M.A., Dory Dickman, M.A., Yuju Ma, M.S., Laura Mufson, Ph.D., Donna Moreau, M.D., Rachel Klein, Ph.D., Lisa Kentgen, Ph.D., Robert Spitzer, M.D., Janet Williams, D.S.W., and Jeffrey Johnson, Ph.D., for their help in different phases of this study.

|

|

1. Regier DA, Burke JD Jr: Psychiatric disorders in the community: the ECA study, in Psychiatry Update: American Psychiatric Association Annual Review, vol 6. Edited by Hales RE, Frances AJ. Washington, DC, American Psychiatric Press, 1987, pp 610–624Google Scholar

2. Robins LN, Helzer JE, Weissman MM, Orvaschel H, Gruenberg E, Burke JD Jr, Regier DA: Lifetime prevalence of specific psychiatric disorders in three sites. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1984; 41:949–958Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

3. Kessler RC, McGonagle KA, Swartz M, Blazer DG, Nelson CB: Sex and depression in the National Comorbidity Survey, I: lifetime prevalence, chronicity and recurrence. J Affect Disord 1993; 29:85–96Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

4. Weissman MM, Leaf PJ, Tischler GL, Blazer DG, Karno M, Livingston B, Florio LP: Affective disorders in five United States communities. Psychol Med 1988; 18:141–153Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

5. Weissman MM, Bland RC, Canino GJ, Faravelli C, Greenwald S, Hwu HG, Joyce PR, Karam EG, Lee CK, Lellouch J, Lepine JP, Newman SC, Rubio-Stipec M, Wells E, Wickramaratne PJ, Wittchen HU, Yeh EK: Cross-national epidemiology of major depression and bipolar disorder. JAMA 1996; 276:293–299Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

6. Hammen C, Burge D, Burney E, Adrian C: Longitudinal study of diagnoses in children of women with unipolar and bipolar affective disorder. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1990; 47:1112–1117Google Scholar

7. Kramer RA, Warner V, Olfson M, Ebanks CM, Chaput F, Weissman MM: General medical problems among the offspring of depressed parents: a 10-year follow-up. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 1998; 37:602–611Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

8. Orvaschel H: Maternal depression and child dysfunction, in Advances in Clinical Child Psychology, vol 6. Edited by Lahey B, Kazdin A. New York, Plenum, 1983, pp 169–197Google Scholar

9. Weissman MM, Warner V, Wickramaratne P, Moreau D, Olfson M: Offspring of depressed parents:10 years later. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1997; 54:932–940Google Scholar

10. Kovacs M, Devlin B, Pollack M, Richards C, Mukerji P: A controlled family history study of childhood onset depressive disorder. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1997; 54:613–623Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

11. Mitchell J, McCauley E, Burke P, Calderon R, Schloredt K: Psychopathology in parents of depressed children and adolescents. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 1989; 28:352–357Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

12. Puig-Antich J, Goetz D, Davies M, Kaplan T, Davies S, Ostrow L, Asnis L, Twomey J, Iyengar S, Ryan ND: A controlled family history study of prepubertal major depressive disorder. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1989; 46:406–418Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

13. Todd RD, Neuman R, Geller B, Fox LW, Hickok J: Genetic studies of affective disorders: should we be starting with childhood onset probands? J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 1993; 32:1164–1171Google Scholar

14. Williamson DE, Ryan ND, Birmaher B, Dahl RE, Kaufman J, Rao U: A case control family history study of depression in adolescents. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 1995; 34:1596–1607Google Scholar

15. Spitzer RL: PRIME-MD Patient Problem Questionnaire. New York, New York State Psychiatric Institute, Biometrics Unit, 1997Google Scholar

16. Spitzer RL, Williams JBW, Gibbon M, First MB: The Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-III-R (SCID), I: history, rationale, and description. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1992; 49:624–629Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

17. Hammen C, Burge D, Adrian C: Timing of mother and child depression in a longitudinal study of children at risk. J Consult Clin Psychol 1991; 59:341–345Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

18. Weissman MM, Bland R, Canino G, Greenwald S, Hwu HG, Joyce PR, Karam EG, Lee CK, Lellouch J, Pine JP, Newman S, Rubio-Stipec M, Wells JE, Wickramaratne P, Wittchen HU, Yeh EK: Prevalence of suicide ideation and suicide attempts in nine countries. Psychol Med 1999; 29:9–17Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

19. Spitzer RL, Williams JB, Kroenke K, Linzer M, deGruy FV III, Hahn SR, Brody D, Johnson JG: Utility of a new procedure for diagnosing mental disorders in primary care: the PRIME-MD 1000 study. JAMA 1994; 272:1749–1756Google Scholar

20. Johnson JG, Spitzer RL, Williams JBW, Kroenke K, Linzer M, Brody D, deGruy F, Hahn S: Psychiatric comorbidity, health status, and functional impairment associated with alcohol abuse and dependence in primary care patients: findings of the PRIME MD-1000 study. J Consult Clin Psychol 1995; 63:133–140Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

21. Weissman MM, Broadhead WE, Olfson M, Sheehan DV, Hoven C, Conolly P, Fireman BH, Farber L, Blacklow RS, Higgins ES, Leon AC: A diagnostic aid for detecting (DSM-IV) mental disorders in primary care. Gen Hosp Psychiatry 1998; 20:1–11Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

22. Myers JK, Weissman MM, Tischler GL, Holzer CE III, Leaf PJ, Orvaschel H, Anthony JC, Boyd JH, Burke JD Jr, Kramer M, Stoltzman R: Six-month prevalence of psychiatric disorders in three communities:1980 to 1982. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1984; 41:959–967Google Scholar

23. Leaf PJ, Livingston MM, Tischler GL, Weissman MM, Holzer CE III, Myers JK: Contact with health professionals for the treatment of psychiatric and emotional problems. Med Care 1985; 23:1322–1337Google Scholar

24. Shapiro S, Skinner EA, Kessler LG, Von Korff M, German PS, Tischler GL, Leaf PJ, Benham L, Cottler L, Regier DA: Utilization of health and mental health services: three Epidemiologic Catchment Area sites. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1984; 41:971–978Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

25. Kessler RC: The National Comorbidity Survey of the United States. Int Rev Psychiatry 1994; 6:365–376Crossref, Google Scholar