Sinoatrial Block in Lithium Toxicity

To The Editor: Lithium carbonate is a mainstay in the treatment of mania and bipolar disorder. A serum level between 0.8 mEq/l and 1.2 mEq/l is considered therapeutic, usually obtained with a dose of approximately 900 to 1200 mg/day (1) . The drug has a narrow therapeutic index, with progressive toxicity ranging from gastrointestinal complaints to marked neurological impairment that correlate with increasing serum levels beginning at about 1.5 mEq/l (2) .

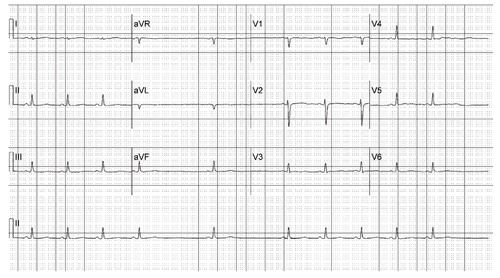

Electrocardiogram (ECG) manifestations, including prolonged QT interval, T wave flattening and inversion, and first-degree atrioventricular (AV) conduction delay, have been reported with lithium toxicity (3 – 6) . In rare cases, ventricular tachycardia and ventricular fibrillation resulting in death have been reported (4) .

Sinoatrial block associated with lithium therapy was first reported in 1975 (7) . Subsequent reports cite reversible sinus node suppression as a consequence of chronic lithium therapy, even at therapeutic levels (8 – 10) . Although the mechanism is poorly understood, it may be related to lithium’s competitive inhibition of calcium in the Na + /Ca ++ exchange in cardiac cells (11) .

The case report presented here demonstrates prominent bradycardia due to second-degree, type II sinoatrial block that resulted from toxic lithium levels.

A 43-year-old woman with a long-standing history of bipolar disorder was started on lithium at 600 mg twice daily, reportedly a lower dose than her chronic therapy, which she had discontinued 1 year before. She was also prescribed naproxen sodium, amitriptyline, and mirtazapine. One week later, she was found to have a lithium level of 3.2 mEq/l (therapeutic level <1.0) and a creatinine level of 2.3 mg/dl. She immediately was sent to the emergency department, and repeated chemistries revealed a further increase in her creatinine level of 4.2 mg/dl and lithium level of 3.64 mEq/l.

Her initial vital signs were normal—she was afebrile; her heart rate was 72 beats per minute and regular; her blood pressure was 117/70 mmHg; and her respiratory rate was 16 breaths per minute with an oxygen saturation of 97% on room air. However, she quickly developed hypothermia at 34.5°C, bradycardia to 36 beats per minute, and hypotension. Other laboratory values were remarkable for hypokalemia with a potassium level of 2.8 mEq/l (normal range: 3.7–5.2), metabolic alkalosis with a serum bicarbonate of 33 mEq/l (normal range: 22–32), and hypochloremia of 88 mEq/l (normal range: 98–108). She was started on norepinephrine and dopamine infusions and transferred to the medical intensive care unit for hemodynamic support and urgent hemodialysis.

The patient’s ECG was remarkable for sinus rhythm/sinus bradycardia consistent with sinoatrial block with an intermittent 2:1 conduction pattern, yielding a variable rate of 78 beats per minute and 39 beats per minute, respectively ( Figure 1 ). Nonspecific T wave flattening was also present with borderline low QRS voltage and a QRS axis of about +90°.

In the case described, second-degree (type II) sinoatrial block was present. The prolonged P-P interval was a direct multiple of the shorter P-P cycles. This is in contrast to second-degree type I sinoatrial block (Wenckebach type), characterized by a sinus pause after progressively decreasing P-P intervals. In such instances, the sinus pause duration is less than two P-P cycles.

The patient’s ECGs also demonstrated 4:3, 5:4, and 6:5 second-degree type I sinoatrial Wenckebach block during dialysis (tracings not shown).

After dialysis, the patient’s lithium level decreased to 0.41 mEq/l. There was no further evidence of sinoatrial block. In this case, renal insufficiency, likely secondary to dehydration in combination with nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory therapy, may have precipitated elevated serum levels of lithium, despite the patient’s initially low dose. In the setting of dehydration and vomiting, the lithium ion is selectively resorbed in the renal tubules, sometimes accumulating to toxic levels. Indeed, the triad of hypokalemia, hypochloremia, and metabolic alkalosis observed on admission was consistent with a history of bulimia nervosa, revealed later in the patient’s hospitalization. Of note, chronic lithium therapy, by itself, may result in renal insufficiency and other renal toxicity (12) .

As the uses of lithium continue to expand with an increasingly larger patient population, clinicians must be mindful of the cardiac risks associated with lithium therapy, including sinoatrial block with resultant bradycardia, which can occur abruptly with chronic therapy.

1. Griswold KS, Pessar LF: Management of bipolar disorder. Am Fam Physician 2000; 62:1343–1353, 1357–1358Google Scholar

2. Hansen HE, Amdisen A: Lithium intoxication: report of 23 cases and review of 100 cases from the literature. Q J Med 1978; 47:123–144Google Scholar

3. Brady HR, Horgan JH: Lithium and the heart: unanswered questions. Chest 1988; 93:166–169Google Scholar

4. Mitchell JE, Mackenzie TB: Cardiac effects of lithium therapy in man: a review. J Clin Psychiatry 1982; 43:47–51Google Scholar

5. Tilkian AG, Schroeder JS, Kao JJ, Hultgren HN: The cardiovascular effects of lithium in man: a review of the literature. Am J Med 1976; 61:665–670Google Scholar

6. Montalescot G, Levy Y, Farge D, Brochard L, Fantin B, Arnoux C, Hatt PYl: Lithium causing a serious sinus-node dysfunction at therapeutic doses. Clin Cardiol 1984; 7:617–620Google Scholar

7. Eliasen P, Andersen M: Sinoatrial block during lithium treatment. Eur J Cardiol 1975; 3:97–98Google Scholar

8. Wellens HJ, Cats VM, Duren DR: Symptomatic sinus node abnormalities following lithium carbonate therapy. Am J Med 1975; 59:285–287Google Scholar

9. Wilson JR, Kraus ES, Bailas MM, Rakita L: Reversible sinus-node abnormalities due to lithium carbonate therapy. N Engl J Med 1976; 294:1223–1224Google Scholar

10. Terao T, Abe H, Abe K: Irreversible sinus node dysfunction induced by resumption of lithium therapy. Acta Psychiatr Scand 1996; 93:407–408Google Scholar

11. Lai CL, Chen WJ, Huang CH, Lin FY, Lee YT: Sinus node dysfunction in a patient with lithium intoxication. J Formos Med Assoc 2000; 99:66–68Google Scholar

12. Boton R, Gaviria M, Batlle DC: Prevalence, pathogenesis, and treatment of renal dysfunction associated with chronic lithium therapy. Am J Kidney Dis 1987; 10:329–345Google Scholar