Randomized Comparison of Olanzapine Versus Risperidone for the Treatment of First-Episode Schizophrenia: 4-Month Outcomes

Abstract

Objective: The authors compared 4-month treatment outcomes for olanzapine versus risperidone in patients with first-episode schizophrenia spectrum disorders. Method: One hundred twelve subjects (70% male; mean age=23.3 years [SD = 5.1]) with first-episode schizophrenia (75%), schizophreniform disorder (17%), or schizoaffective disorder (8%) were randomly assigned to treatment with olanzapine (2.5–20 mg/day) or risperidone (1–6 mg/day). Results: Response rates did not significantly differ between olanzapine (43.7%, 95% CI=28.8%–58.6%) and risperidone (54.3%, 95% CI=39.9%–68.7%). Among those responding to treatment, more subjects in the olanzapine group (40.9%, 95% CI=16.8%–65.0%) than in the risperidone group (18.9%, 95% CI=0%–39.2%) had subsequent ratings not meeting response criteria. Negative symptom outcomes and measures of parkinsonism and akathisia did not differ between medications. Extrapyramidal symptom severity scores were 1.4 (95% CI=1.2–1.6) with risperidone and 1.2 (95% CI=1.0–1.4) with olanzapine. Significantly more weight gain occurred with olanzapine than with risperidone: the increase in weight at 4 months relative to baseline weight was 17.3% (95% CI=14.2%–20.5%) with olanzapine and 11.3% (95% CI=8.4%–14.3%) with risperidone. Body mass index at baseline and at 4 months was 24.3 (95% CI=22.8–25.7) versus 28.2 (95% CI=26.7–29.7) with olanzapine and 23.9 (95% CI=22.5–25.3) versus 26.7 (95% CI=25.2–28.2) with risperidone. Conclusions: Clinical outcomes with risperidone were equal to those with olanzapine, and response may be more stable. Olanzapine may have an advantage for motor side effects. Both medications caused substantial rapid weight gain, but weight gain was greater with olanzapine.

The critical choice of the initial antipsychotic medication for patients experiencing a first episode of psychosis must be based upon research data and not, unlike with multiepisode patients, individual past response to treatment. Current information about treatment of first-episode patients with second-generation antipsychotics is limited to trials comparing first- and second-generation agents. Four large studies have been published that compared clozapine versus chlorpromazine in 160 subjects (1) ; risperidone versus haloperidol in 183 subjects (2) and 555 subjects (3) ; and olanzapine versus haloperidol in 263 subjects (4) . None found significant differences in positive symptom response rates. Advantages for second-generation agents for treating negative symptoms were found in some studies (1 , 4) but not others (2) . The second-generation antipsychotics became the standard treatment for first-episode patients in part because of concerns about the risk of tardive dyskinesia in first-episode patients treated even with low doses of first-generation agents (5) . However, the published first-episode trials do not address the question of which second-generation agent is better for these patients. With multiepisode patients, the Clinical Antipsychotic Trials of Intervention Effectiveness (CATIE) study found efficacy advantages, but more metabolic side effects, with olanzapine compared with risperidone, quetiapine, or ziprasidone treatment (6) . Are the CATIE results generalizable to treatment for first-episode patients?

To address choice of the initial antipsychotic, we report data comparing olanzapine with risperidone on treatment response and side effects during the initial 4 months of treatment. These data derive from an ongoing study assessing first-episode subjects over 3 years.

Method

Settings

The study was conducted at two not-for-profit facilities. The Zucker Hillside Hospital serves a low- to middle-class population, and Bronx-Lebanon serves a mostly poor and primarily minority community.

Subjects

After complete description of the study, written informed consent was obtained from all adult subjects and, if available, from a family member. For subjects less than 18 years old, written parental consent and written subject assent was obtained.

Inclusion criteria were as follows: 1) current diagnosis of DSM-IV schizophrenia, schizophreniform disorder, or schizoaffective disorder; 2) age 16 to 40; 3) less than 12 weeks of lifetime antipsychotic medication treatment; 4) current positive symptoms evidenced by a rating of 4 or more on the severity of delusions, hallucinations, or thought disorder items of the Schedule for Affective Disorders and Schizophrenia Change Version with psychosis and disorganization items (SADS-C+PD) or current negative symptoms demonstrated by a rating of 4 or more on the affective flattening, alogia, avolition, or anhedonia global items of the Hillside Clinical Trials version (7) of the Scale for Assessment of Negative Symptoms (SANS); 5) for women, a negative pregnancy test and agreement to use a medically accepted method of birth control; and 6) competent and willing to sign informed consent. Exclusion criteria were 1) meeting DSM-IV criteria for a current substance-induced psychotic disorder, psychotic disorder due to a general medical condition, or mental retardation; 2) medical condition/treatment known to affect the brain; 3) any medical condition requiring treatment with a medication with psychotropic effects; 4) medical contraindications to treatment with olanzapine or risperidone; or 5) significant risk of suicidal or homicidal behavior.

Treatment Protocol

Because we believed that treatment with blinded medication for 3 years would be unacceptable to most first-episode patients, our design employed random assignment with open-label treatment. Outcome assessments were done by masked (“blind”) raters.

Patients were stratified by sex, current DSM-IV-defined substance abuse or dependence (excluding nicotine and caffeine), and site and randomly assigned to treatment with olanzapine or risperidone. Our goal was to find the lowest effective dose. The initial daily dose was 2.5 mg for olanzapine and 1 mg for risperidone. A slowly increasing titration schedule was used: after week 1, dose increases occurred at intervals of 1–3 weeks until the subject improved or reached a maximum daily dose of 20 mg of olanzapine or 6 mg of risperidone. Lorazepam was given for agitation requiring pharmacological treatment. Subjects with persistent mood symptoms unresponsive to antipsychotic treatment were prescribed sertraline for depression or divalproex sodium for manic symptoms. Motor side effects were treated with antipsychotic dose reduction or, if this was ineffective, benztropine for extrapyramidal symptoms and lorazepam or propranolol for akathisia.

The acute treatment phase lasted 4 months. Because of concern about maintaining psychotic subjects for 4 months on an ineffective treatment, subjects who did not achieve Clinical Global Impression (CGI) ratings of at least minimal improvement by 10 weeks were terminated from controlled treatment.

Assessments

Subject diagnoses were determined with the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Axis I Disorders (SCID). Psychopathology was assessed with the SADS-C+PD, CGI, and Hillside Clinical Trials version of the SANS. Motor side effects were assessed with the Simpson-Angus Rating Scale and Barnes Akathisia Scale. Assessments (except the SCID) were completed every week for the first 4 weeks, then every 2 weeks. The diagnosis/psychopathology assessments and the side effect assessments were performed by different masked assessors to minimize the possibility that raters of psychopathology might be influenced by knowledge of side effects. Weight data were obtained by nonblind study personnel.

To increase uniformity of assessments, a central rater team performed the masked assessments at both sites. The same raters performed assessments with individual subjects throughout that subject’s study participation. Intraclass correlation coefficients with three psychopathology raters for the items comprising the positive symptom response criteria were as follows: severity of delusions=0.79; severity of hallucinations=0.90; impaired understandability=0.66; derailment=0.67; illogical thinking=0.82; bizarre behavior=0.97; and CGI severity=0.63. Intraclass correlation coefficients for the global items of the SANS ranged from 0.66 to 0.82.

Outcome Definitions

A treatment should be considered successful for young patients just beginning treatment only if the treatment produces sustained substantial improvement. We defined substantial improvement a priori as a rating of mild or better on the SADS-C+PD positive symptom items (severity of delusions, severity of hallucinations, impaired understandability, derailment, illogical thinking, and bizarre behavior) plus a CGI rating of much improved or very much improved. The response criteria required that substantial improvement be maintained for two consecutive visits.

Parkinsonism was defined as being present if two or more of the Simpson-Angus Rating Scale items (gait, rigidity of major joints, tremor, akinesia, and akathisia) were rated 2 or one item was rated 3 or higher. An overall extrapyramidal symptom severity score was calculated as the sum of the Simpson-Angus Rating Scale items.

Statistical Analysis

Subjects were included if they took one dose of medication following random assignment regardless of subsequent time in study. Statistical tests for comparisons between the two groups on baseline characteristics included two-sample t tests for continuous variables and chi-square or Fisher’s exact tests for categorical variables.

Cumulative rates of response were computed and compared using standard survival analysis methods, i.e., Kaplan-Meier product-limit method and the log-rank test. Time to treatment response was coded as the first of the two visits meeting substantial improvement criteria. Median time to response could not be estimated because time-until-response curves generally did not cross 50%. Mean time until response is reported instead.

Repeated-measures analysis of covariance (ANCOVA) using a mixed model approach was used to examine the longitudinal and between-drug patterns of positive and negative symptoms. The three positive symptom models examined the SADS-C+PD items severity of delusions and severity of hallucinations and a measure of thought disorder (the sum of the ratings for the SADS-C+PD items impaired understandability, derailment, and illogical thinking). The four negative symptom models examined the SANS global measures affective flattening, alogia, avolition-apathy, and asociality-anhedonia. Factors in each of the initial models were the two medications, time, the two study sites, and the medication-by-time interaction. The medication-by-time interaction was removed from each of the seven final models.

Time until the emergence of parkinsonism was computed and compared using the Kaplan-Meier product-limit method and the log-rank test. Repeated-measures ANCOVA was used to analyze the extrapyramidal symptom severity score data as well as the global item of the Barnes Akathisia Scale. Factors in the initial models included medication, time, site, and the medication-by-time interaction. The medication-by-time interaction was removed from the final model in both analyses.

Weight data were analyzed using a mixed models approach to repeated-measures ANCOVA. The dependent measure was the log of the ratio of the subject’s weight at each visit relative to their baseline weight. Factors in the initial models included medication, time, site, and the medication-by-time interaction. The medication-by-time interaction was removed from the final model. The same models were used to examine changes in body mass index (BMI).

Secondary Analyses

We examined the stability of response among subjects who met response criteria. Subjects were classified as failing to maintain response during the acute treatment phase if they no longer met criteria for substantial improvement at any time after the two visits that established their treatment responder status. Cumulative rates of failure to maintain response were compared using survival analysis. Time until failure to maintain response was the time between the first visit establishing treatment response and the first visit that no longer met the substantial improvement definition.

To evaluate possible effects of substance use and adjuvant medications on weight gain, we performed a second repeated-measures ANCOVA using an expanded model. These analyses included six substance use measures covering alcohol, marijuana, and other psychoactive substance use before randomization and also during the trial (classification methods are available upon request). The initial model included the following independent measures: antipsychotic medication, time, antipsychotic medication-by-time interaction, site, the substance abuse measures, sertraline use (time dependent), sertraline-by-antipsychotic medication interaction, divalproex use (time dependent), and divalproex-by-antipsychotic medication interaction. The antipsychotic medication-by-time interaction, site, substance use measures, sertraline, and sertraline-by-antipsychotic medication interaction were removed from the final model.

Results

Data for this report were collected from November 1998 to October 2004.

Subjects

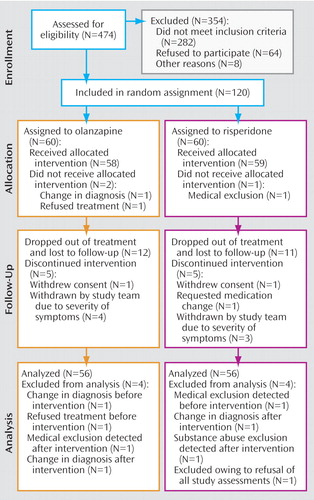

Figure 1 presents the subject flow. The subjects were young (mean age=23.3 years [SD=5.1]), mostly male (70%), of diverse ethnic backgrounds, and usually from low to lower middle class socioeconomic backgrounds. Subjects had psychotic symptoms for an average of slightly over 2 years before study entry. At entry, 87 subjects (78%) were antipsychotic medication naive, and 15 (13%) had only 1 to 7 days of lifetime antipsychotic medication use. Eighty-four subjects (75%) met criteria for schizophrenia, 19 (17%) for schizophreniform disorder, and nine (8%) for schizoaffective disorder. Subjects had substantial positive symptoms at study entry; the mean ratings of severity for both delusions and hallucinations were close to 5, a severity level requiring that symptoms have “a significant effect” on behavior. Negative symptoms were less pronounced; the mean ratings on the SANS global items varied from approximately 2 (mild) to 3 (moderate). Additional characteristics of the group as a whole as well as by treatment group are presented in a supplement that accompanies the online version of this article. Subjects assigned to olanzapine and risperidone did not differ on any baseline characteristics.

Protocol Implementation

Eighty-one (72%) of the 112 subjects completed 4 months of study participation. Seven subjects (four taking olanzapine and three taking risperidone) were removed from controlled treatment before 4 months because of the severity of their symptoms or inadequate response. Olanzapine- and risperidone-treated subjects had similar lengths of study participation during the trial: 11.5 weeks (95% CI=10.21–12.76) for the olanzapine group and 12.05 weeks (95% CI=11.53–12.57) for the risperidone group (log-rank test, χ 2 =0.10, df=1, p<0.75). The mean modal daily dose was 11.8 mg (SD=5.4) for olanzapine-treated subjects and 3.9 mg (SD=1.5) for risperidone-treated subjects. Twelve subjects (five receiving olanzapine and seven receiving risperidone) were given divalproex at some point during the trial, and seven subjects (three receiving olanzapine and four receiving risperidone) were given sertraline. Twenty-nine subjects (10 receiving olanzapine and 19 receiving risperidone) required benztropine, and 14 (four receiving olanzapine and 10 receiving risperidone) required propranolol. Lorazepam was prescribed for 42 olanzapine-treated and 44 risperidone-treated subjects.

Symptom Response

Cumulative response rates by 4 months were similar with olanzapine (43.7%, 95% CI=28.8%–58.6%) and risperidone (54.3%, 95% CI=39.9%–68.7%) ( Figure 2 ). Mean time to response was 10.9 weeks (95% CI=9.7–12.2) with olanzapine and 10.4 weeks (95% CI=9.1–11.7) with risperidone. Mean daily dose at the time of response for subjects who responded to olanzapine was 8.9 mg (SD=5.1) and 3.4 mg (SD=1.2) with risperidone.

a Log-rank test, olanzapine versus risperidone: χ 2 =0.87, p<0.35.

b Log-rank test, olanzapine versus risperidone: χ 2 =0.30, p<0.59.

c Log-rank test, olanzapine versus risperidone: χ 2 =0.61, p<0.44.

As shown in Figure 3 , approximately twice as many subjects who responded to olanzapine (40.9%, 95% CI=16.8%–65.0%) compared with risperidone (18.9%, 95% CI=0%–39.2%) later had ratings no longer meeting substantial improvement criteria, but the difference fell short of statistical significance (log-rank test, χ 2 =3.02, p<0.08). The mean length of time that subjects maintained their responder status was 6.6 weeks (95% CI=5.6–7.7) with olanzapine and 9.5 weeks (95% CI=8.6–10.4) with risperidone.

a Log-rank test, olanzapine versus risperidone, χ 2 =3.02, p<0.08.

b Log-rank test, olanzapine versus risperidone, χ 2 =1.94, p<0.16.

c All subjects at Bronx-Lebanon who responded to risperidone treatment maintained this response. Log-rank test, olanzapine versus risperidone: χ 2 =1.25, p<0.26.

There were no significant differences between medications and no medication-by-time interactions in analyses of the delusions, hallucinations, and thought disorder measures. Delusions (F=19.92, df=11, 853, p<0.0001), hallucinations (F=23.53, df=11, 853, p<0.0001), and thought disorder (F=14.02, df=11, 853, p<0.0001) improved over time. Thought disorder severity differed across sites (F=7.28, df=1, 109, p<0.01), with higher ratings seen among subjects at The Zucker Hillside (5.0, 95% CI=4.5–5.4) than among those at Bronx-Lebanon (3.9, 95% CI=3.3–4.6).

There were no significant differences between medications and no medication-by-time interactions in analyses with the SANS global measures for affective flattening, alogia, avolition-apathy, and asociality-anhedonia. Only avolition-apathy (F=2.43, df=11, 816, p<0.01) and asociality-anhedonia (F=5.29, df=11, 816, p<0.0001) improved significantly over time. The estimate of adjusted mean for avolition-apathy at baseline was 2.9 (95% CI=2.7–3.1); the lowest value across time was 2.4 (95% CI=2.4–2.9) at week 6. For asociality-anhedonia, the corresponding results were 3.0 (95% CI=2.8–3.3) at baseline and 2.4 (95% CI=2.2–2.6) at week 4. Subjects at The Zucker Hillside were rated higher than those at Bronx-Lebanon on affective flattening (2.2 [95% CI=2.1–2.4] versus 1.7 [95% CI=1.4–2.0]; F=11.10, df=1, 109, p<0.01), alogia (1.9 [95% CI=1.8–2.1] versus 1.4 [95% CI=1.2–1.7]; F=10.29, df=1, 109, p<0.01), and asociality-anhedonia (2.8 [95% CI=2.6–2.9] versus 2.4 [95% CI=2.1–2.6]; F=6.50, df=1, 109, p<0.01).

Side Effects

The cumulative rate of parkinsonism did not differ significantly between medications; the rate was 8.9% (95% CI=0.3%–17.6%) with olanzapine and 16.0% (95% CI=5.5%–26.6%) with risperidone. Significant effects of time (F=2.33, df=11, 877, p<0.01) and site (F=4.25, df=1, 109, p<0.04) were revealed in analysis of the extrapyramidal symptom severity score data, but there was no time-by-treatment interaction. Simpson-Angus Rating Scale scores were slightly higher for Bronx-Lebanon subjects (1.4; 95% CI=1.2–1.7) than for The Zucker Hillside subjects (1.1; 95% CI=1.0–1.3). The extrapyramidal symptom score of risperidone-treated subjects (1.4, 95% CI=1.2–1.6) was slightly higher than that of olanzapine-treated subjects (1.2, 95% CI=1.0–1.4), but the difference fell short of statistical significance (F=3.42, df=1, 109, p<0.07). The repeated-measures ANOVA of the Barnes global akathisia item revealed a significant site difference (F=5.64, df=1, 109, p<0.02) but no effects of medication assignment or time. Subjects at Bronx-Lebanon had slightly more akathisia (0.4, 95% CI=0.3–0.5) than subjects at The Zucker Hillside (0.3, 95% CI=0.2–0.3). More subjects taking risperidone than olanzapine were prescribed benztropine for extrapyramidal symptoms, but the difference was not significant (χ 2 =3.8, df=1, p<0.06). Prescription of propranolol for akathisia followed the same pattern (χ 2 =2.9, df=1, p<0.09).

The mean weight at study entry for all subjects was 70.1 kg (SD=16.6). The primary weight analyses based upon the entire 4-month period revealed an increase of weight over time (F=16.63, df=15, 469, p<0.001) and more weight gain with olanzapine compared with risperidone (F=8.01, df=1, 88, p<0.01). No medication-by-time interaction or site differences were found. Results of the analyses of the BMI data were the same as the analyses using weight as the dependent measure. The percent weight gain from baseline to 4 months was 17.3% (95% CI=14.2%–20.5%) with olanzapine and 11.3% (95% CI=8.4%–14.3%) with risperidone. The estimate of adjusted mean of BMI increased from 24.3 (95% CI=22.8–25.7) at baseline to 28.2 (95% CI=26.7–29.7) at 4 months with olanzapine and from 23.9 (95% CI=22.5–25.3) to 26.7 (95% CI=25.2–28.2) with risperidone.

Our secondary weight analyses revealed a significant increase of weight with time (F=16.66, df=15, 467, p<0.0001) and an antipsychotic-by-divalproex interaction (F=11.28, df=1, 9, p<0.01) but no significant effects of site, substance use, sertraline use, or the interactions of antipsychotic medication by time or sertraline by antipsychotic medication. The weight gain associated with combined olanzapine and divalproex treatment was more than with olanzapine alone (t=2.96, df=9, p<0.02), risperidone alone (t=3.90, df=9, p<0.01), or risperidone combined with divalproex (t=4.43, df=9, p<0.01). Treatment with olanzapine alone was associated with more weight gain than with risperidone alone (t=2.51, df=9, p<0.03) or risperidone plus divalproex (t=3.28, df=9, p<0.01). Weight gain with risperidone alone and risperidone plus divalproex did not differ significantly (t=1.90, df=9, p<0.09). Percent gains from baseline weight at 4 months for each medication condition were as follows: olanzapine plus divalproex, 25.1% (95% CI=19.3%–31.3%); olanzapine alone, 15.9% (95% CI=12.7%–19.1%); risperidone alone, 11.2% (95% CI=8.1%–14.5%); risperidone plus divalproex, 10.9% (95% CI=6.2%–15.8%).

Discussion

Efficacy

Our data are consistent with the findings from many studies (8) that antipsychotic medication treatment of the initial episode of schizophrenia produces substantial positive symptom improvement. After up to 4 months of treatment, about half of our subjects met criteria for response, which required an absence of delusions, hallucinations, or significant thought disorder. Changes in negative symptoms were less pronounced; we found modest improvements in avolition-apathy and asociality-anhedonia.

The 18-month CATIE trial with multiepisode patients reported better symptom response for olanzapine treatment compared with risperidone: time to discontinuation of medication due to lack of efficacy was longer for subjects taking olanzapine than those taking risperidone. In contrast, we found no significant differences between olanzapine and risperidone in rates of positive symptom response or overall severity of positive or negative symptoms and a nonsignificant (p<0.08) difference in response stability that favored risperidone. Potential causes of these divergent findings include different illness stages (first-episode versus multiepisode), illness severity at study entry (acutely psychotic in our study versus mixed severity of symptoms in CATIE), differences in length of treatment and dosing, and substantial differences in outcome measures. In the CATIE study, the antipsychotic taken before study entry affected outcome; patients switched to a different antipsychotic did worse than subjects assigned to their baseline medication (9) . Prior medication treatment is not a factor in first-episode treatment studies such as ours.

Side Effects

We found differences that approached statistical significance in extrapyramidal symptom severity scores and in prescription of benztropine and propranolol favoring olanzapine over risperidone. These findings are consistent with the results of a meta-analysis (10) indicating that risperidone has a slightly less favorable extrapyramidal symptom profile than olanzapine with multiepisode patients. Our finding of rapid, substantial weight gain with both olanzapine and risperidone is consistent with data from two large first-episode trials (3 , 4) . Compared with multiepisode patients, first-episode patients may be more susceptible to antipsychotic-induced weight gain due to being younger (11) or other factors. Olanzapine-treated multiepisode subjects in the CATIE trial gained a mean of 9.4 pounds after a median follow-up of 9.2 months. After only 4 months of olanzapine treatment, substantially more average weight gain was found in our study as well as another first-episode study (4) . Although the amount of weight gain may be more with first-episode patients, our finding that weight gain was more pronounced with olanzapine than with risperidone is consistent with data with multiepisode patients (6 , 12 – 14) .

Study Limitations

Open-label masked assessment designs allow the possibility that patient or staff bias in favor of one of the medications might influence the results. We expected subject bias to be minimal given that subjects had very limited experience with antipsychotics. Staff bias might be reflected in a difference in team decisions to remove subjects from controlled treatment before trial completion. We found that this occurred equally with the two medications. Another issue is that the study was designed to detect differences in our primary analyses at α=0.05 with 80% power based upon 130 subjects. The stability analyses included only 47 subjects and therefore might lack adequate power. Nonetheless, there was a relatively small probability (8%) that we found a difference between medications if one does not exist. The primary analyses included 112 subjects and may also lack adequate power. Future studies with larger sample sizes may be useful to confirm our results. Finally, interpretation of our secondary weight change analyses is limited by the fact that divalproex, unlike olanzapine and risperidone, was not randomly assigned and that few subjects were given divalproex.

Clinical Implications

Based upon CATIE and other data, an olanzapine trial has been suggested for any patient with schizophrenia who has not yet had a full remission of illness (15) . Does this suggest that clinicians should use olanzapine as the initial antipsychotic with first-episode patients? We found that clinical outcomes with risperidone were as good as or better than with olanzapine, suggesting that data from studies with multiepisode patients may not be the best basis for treatment decisions with first-episode patients. Olanzapine treatment may have an advantage for motor side effects, although the differences between olanzapine and risperidone on measures of motor side effects in our study did not reach statistical significance. Given the difficulty of reversing weight gain after it occurs (16 – 24) , the adverse effects of obesity on health (25 – 27) , and the frequency of cardiovascular disease as a cause of mortality among patients with schizophrenia (28) , the medication differences favoring risperidone on weight gain may be more important long-term with most patients. Of note, the weight gain (25% of baseline weight) associated with the combination of olanzapine and divalproex is striking, suggesting caution about using this combination with first-episode populations. Even with risperidone treatment, our subjects’ average BMI increased from the normal to the overweight range in only 4 months. A crucial unanswered question deserving investigation is whether newer second-generation antipsychotics with lower propensity to cause metabolic side effects might be the most appropriate first treatments.

1. Lieberman JA, Phillips M, Gu H, Stroup S, Zhang P, Kong L, Ji Z, Koch G, Hamer RM: Atypical and conventional antipsychotic drugs in treatment-naive first-episode schizophrenia: a 52-week randomized trial of clozapine versus chlorpromazine. Neuropsychopharmacology 2003; 28:995–1003Google Scholar

2. Emsley RA, the Risperidone Working Group: Risperidone in the treatment of first-episode psychotic patients: a double-blind multicenter study. Schizophr Bull 1999; 25:721–729Google Scholar

3. Schooler N, Rabinowitz J, Davidson M, Emsley R, Harvey PD, Kopala L, McGorry PD, Van Hove I, Eerdekens M, Swyzen W, De Smedt G, Early Psychosis Global Working Group: Risperidone and haloperidol in first episode psychosis: a long-term randomized trial. Am J Psychiatry 2005; 162:947–953Google Scholar

4. Lieberman JA, Tollefson G, Tohen M, Green AI, Gur RE, Kahn R, McEvoy J, Perkins D, Sharma T, Zipursky R, Wei H, Hamer RM, HGDH Study Group: Comparative efficacy and safety of atypical and conventional antipsychotic drugs in first-episode psychosis: a randomized double-blind trial of olanzapine versus haloperidol. Am J Psychiatry 2003; 160:1396–1404Google Scholar

5. Oosthuizen PP, Emsley RA, Maritz JS, Turner JA, Keyter N: Incidence of tardive dyskinesia in first-episode psychosis patients treated with low-dose haloperidol. J Clin Psychiatry 2003; 64:1075–1080Google Scholar

6. Lieberman JA, Stroup TS, McEnvoy JP, Swartz MS, Rosenheck RA, Perkins DO, Keefe RSE, Davis SM, Davis CE, Lebowitz BD, Severe J, Hsiao JK: Effectiveness of antipsychotic drugs in patients with chronic schizophrenia. N Engl J Med 2005; 353:1209–1223Google Scholar

7. Robinson D, Woerner M, Schooler N: Intervention research in psychosis: issues related to clinical assessment. Schizophr Bull 2000; 26:551–556Google Scholar

8. Robinson DG, Woerner MG, Delman H, Kane JM: Pharmacological treatments for first-episode schizophrenia. Schizophr Bull 2005; 31:705–722Google Scholar

9. Lieberman JA, Stroup TS, Davis SM: Antipsychotic drugs and schizophrenia (letter). N Engl J Med 2005; 354: 300Google Scholar

10. Leucht S, Pitschel-Walz G, Abraham D, Kissling W: Efficacy and extrapyramidal side-effects of the new antipsychotics olanzapine, quetiapine, risperidone, and sertindole compared to conventional antipsychotics and placebo: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Schizophr Res 1999; 35:51–68Google Scholar

11. Safer DJ: A comparison of risperidone-induced weight gain across the age span. J Clin Psychopharmacol 2004; 24:429–436Google Scholar

12. Tran PV, Hamilton SH, Kuntz AJ, Potvin JH, Andersen SW, Beasley C Jr, Tollefson GD: Double-blind comparison of olanzapine versus risperidone in the treatment of schizophrenia and other psychotic disorders. J Clin Psychopharmacol 1997; 17:405–418Google Scholar

13. Conley RR, Mahmoud R: A randomized double-blind study of risperidone and olanzapine in the treatment of schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder. Am J Psychiatry 2001; 158:765–774Google Scholar

14. Jeste DV, Barak Y, Madhusoodanan S, Grossman F, Gharabawi G: International multisite double-blind trial of the atypical antipsychotics risperidone and olanzapine in 175 elderly patients with chronic schizophrenia. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry 2003; 11:638–647Google Scholar

15. Freedman R: The choice of antipsychotic drugs for schizophrenia. N Engl J Med 2005; 353:1286–1288Google Scholar

16. Ball MP, Coons VB, Buchanan RW: A program for treating olanzapine-related weight gain. Psychiatr Serv 2001; 52:967–969Google Scholar

17. Cohen S, Glazewski R, Khan S, Khan A: Weight gain with risperidone among patients with mental retardation: effect of calorie restriction. J Clin Psychiatry 2001; 62:114–116Google Scholar

18. Gracious BL, Krysiak TE, Youngstrom EA: Amantadine treatment of psychotropic-induced weight gain in children and adolescents: case series. J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol 2002; 12:249–257Google Scholar

19. Morrison JA, Cottingham EM, Barton BA: Metformin for weight loss in pediatric patients taking psychotropic drugs. Am J Psychiatry 2002; 159:655–657Google Scholar

20. Yanovski SZ, Yanovski JA: Obesity. N Engl J Med 2002; 346:591–602Google Scholar

21. Vreeland B, Minsky S, Menza M, Rigassio Radler D, Roemheld-Hamm B, Stern R: A program for managing weight gain associated with atypical antipsychotics. Psychiatr Serv 2003; 54:1155–1157Google Scholar

22. Nemeroff CB: Safety of available agents used to treat bipolar disorder: focus on weight gain. J Clin Psychiatry 2003; 64:532–539Google Scholar

23. Birt J: Management of weight gain associated with antipsychotics. Ann Clin Psychiatry 2003; 15:49–58Google Scholar

24. Bray GA, Hollander P, Klein S, Kushner R, Levy B, Fitchet M, Perry BH: A 6-month randomized, placebo-controlled, dose-ranging trial of topiramate for weight loss in obesity. Obes Res 2003; 11:722–733Google Scholar

25. National Task Force on the Prevention and Treatment of Obesity. Overweight, obesity, and health risk. Arch Intern Med 2000; 160:898–904Google Scholar

26. American Diabetes Association: Report of the expert committee on the diagnosis and classification of diabetes mellitus. Diabetes Care 2001; 24 (suppl 1):S5-S20Google Scholar

27. Calle EE, Rodriguez C, Walker-Thurmond K, Thun MJ: Overweight, obesity, and mortality from cancer in a prospectively studied cohort of US adults. N Engl J Med 2003; 348:1625–1638Google Scholar

28. Brown S: Excess mortality of schizophrenia: a meta-analysis. Br J Psychiatry 1997; 171:502–508Google Scholar