Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder: Prevalence, Comorbidity, Impact, and Help-Seeking in the British National Psychiatric Morbidity Survey of 2000

Abstract

Objective: There is little information about obsessive-compulsive disorder in large representative community samples. The authors aimed to establish obsessive-compulsive disorder prevalence and its clinical typology among adults in private households in Great Britain and to obtain generalizable estimates of impairment and help-seeking. Method: Data from the British National Psychiatric Morbidity Survey of 2000, comprising 8,580 individuals, were analyzed using appropriate measurements. The study compared individuals with obsessive-compulsive disorder, individuals with other neurotic disorders, and a non-neurotic comparison group. ICD-10 diagnoses were derived from the Clinical Interview Schedule–Revised. Results: The authors identified 114 individuals (74 women, 40 men) with obsessive-compulsive disorder, with a weighted 1-month prevalence of 1.1%. Most individuals (55%) in the obsessive-compulsive group had obsessions only. Comorbidity occurred in 62% of these individuals, which was significantly greater than the group with other neuroses (10%). Co-occurring neuroses were depressive episode (37%), generalized anxiety disorder (31%), agoraphobia or panic disorder (22%), social phobia (17%), and specific phobia (15%). Alcohol dependence was present in 20% of participants, mainly men, and drug dependence was present in 13%. Obsessive-compulsive disorder, compared with other neurotic disorders, was associated with more marked social and occupational impairment. One-quarter of obsessive-compulsive disorder participants had previously attempted suicide. Individuals with pure and comorbid obsessive-compulsive disorder did not differ according to most indices of impairment, including suicidal behavior, but pure individuals were significantly less likely to have sought help (14% versus 56%). Conclusions: A rare yet severe mental disorder, obsessive-compulsive disorder is an atypical neurosis, of which the public health significance has been underestimated. Unmet need among individuals with pure obsessive-compulsive disorder is a cause for concern, requiring further investigation of barriers to care and interventions to encourage help-seeking.

Epidemiological data based on representative community samples are essential for the proper planning and prioritization of mental health services (1) . This is particularly true for obsessive-compulsive disorder, which has been described as a hidden disease (2 , 3) because many sufferers are embarrassed and secretive about their symptoms and may not seek professional help. Sociodemographic factors, severity, and comorbid disorders may all influence treatment-seeking behaviors (3) . Therefore, it is important to study the distribution and characteristics of the disorder beyond clinical settings (4 , 5) .

Currently, there is limited information on the epidemiology of obsessive-compulsive disorder and comorbid psychiatric disorders based on suitable standardized diagnostic instruments (4) , especially with random samples of the total population. The first National Comorbidity Survey (6) did not include obsessive-compulsive disorder. Fourteen epidemiological studies that used the Present State Examination identified only one individual with the disorder because of the exam’s rigid hierarchical structure and exclusion criteria (7) . The Epidemiological Catchment Area Study (8) comprised individuals from only five sites in the United States; most epidemiological studies in other countries were also restricted to specific centers (9) .

In this study, we sought to assess the prevalence of obsessive-compulsive disorder and comorbid neuroses and alcohol and substance use in adults who participated in the British National Psychiatric Morbidity Survey of 2000. Sociodemographic factors, comorbidity, indicators of impairment, and help-seeking were compared between participants with obsessive-compulsive disorder, participants with other neurotic disorders, and a non-neurotic comparison group. To our knowledge, this is the first such analysis from a large national, representative survey.

We hypothesized that participants with obsessive-compulsive disorder would have a high prevalence of comorbid neurotic disorders, with a predominance of depressive episode, phobias, panic and generalized anxiety disorders among women and of substance use disorders among men. We expected those individuals with both obsessions and compulsions, with other co-occurring neuroses, and males to have more psychosocial impairment and to be receiving more treatment.

Method

The British National Psychiatric Morbidity Survey of 2000 was the second in a series of national government-sponsored surveys intended to monitor prevalence, impact, and treatment of psychiatric illness, thereby informing policy and provision (10) . Major design features of the survey are described in this study, but further methodological details are available elsewhere (10 , 11) .

Sample

The psychiatric morbidity survey included individuals aged 16 to 74 living in private households in England, Wales, and Scotland. The primary sampling units were 438 postcode sectors randomly selected from the Postcode Address File, stratified by region and socioeconomic group. Thirty-six addresses were selected randomly from each sampling unit. One eligible person was selected randomly per household, using the Kish Grid method (12) .

Instruments

The instrument used to assess neurotic disorders was the Clinical Interview Schedule-Revised (13 , 14) , which is made up of subsections covering 14 different symptom clusters. Initial filter questions in each section establish the existence of a particular symptom in the past month, leading to a more detailed assessment focusing on the past week. Symptoms within each cluster are summed to create an overall psychological morbidity score. Additional questions enable ICD-10 diagnostic criteria (15) to be applied using computerized algorithms. Six diagnostic categories were obtained: obsessive-compulsive disorder, generalized anxiety disorder, depressive episode, phobias, panic disorder, and mixed anxiety and depressive disorders (10) .

The Clinical Interview Schedule-Revised has eight questions concerning obsessions and compulsions. The obsession score relates to the respondent’s experience of repetitive unpleasant thoughts or ideas in the past week, while the compulsion score relates to the respondent’s experience of doing things repeatedly. One point was assigned for each of the following criteria: 1) symptoms present 4 or more days, 2) the respondent tried to stop thinking any repetitive unpleasant thoughts or repeating behaviors, 3) symptoms made the respondent upset or annoyed, and 4) the respondent experienced an episode of obsession lasting at least 15 minutes or a behavior repeated at least three times. The algorithm for generating obsessive-compulsive disorder ICD-10 diagnosis required a symptom duration of 2 weeks or longer, at least one act or thought resisted, and an overall score of 4 for obsessions or compulsions if accompanied by social impairment or at least 6 if not accompanied by social impairment (16) . Participants with obsessive-compulsive disorder were considered to have pure obsessions, pure compulsions, or mixed disorder depending upon whether two or more points out of four were scored for any or all of these symptom groups. Obsessive-compulsive disorder participants were defined as pure if they did not meet criteria for other ICD-10 neurotic disorders and comorbid if they did meet criteria (comorbidity with alcohol and substance use disorder was not considered, with respect to this definition).

Drinking problems were assessed through the Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test (17) and the Severity of Alcohol Dependence Questionnaire (18) . A combination of these two measures was used in this study to define hazardous alcohol use and dependence, while five questions taken from the Epidemiological Catchment Area Study (8) were used to assess other drug use and dependence in the past year.

Data Collection Procedure

Trained nonclinical interviewers carried out the initial computer-assisted structured interviews. These were completed on 8,580 individuals, with a response rate of 69.5%. The alcohol and drug section was self-completed. Although a second interview phase was conducted for diagnostic assessment of psychosis and personality disorder, the full assessment of sociodemographic characteristics, impairment, use of services, neurotic psychopathology, and substance misuse was made in the first phase for all participants, together with screening for psychosis and personality disorder.

Statistical Analyses

Statistical analyses were conducted using STATA Version 8 software (College Station, Tex.) (19) . Because of the multistage stratified sampling design, all analyses were weighted to account for differing selection probabilities at each stage and for nonresponse using poststratification. All estimates of prevalence and association were made using the appropriate STATA survey commands to generate robust standard errors. Sociodemographic status, prevalence of comorbid neuroses and alcohol and substance use disorder, and various measures of impaired quality of life were compared between individuals with obsessive-compulsive disorder, individuals with other neuroses, and a non-neurotic comparison group using the chi-square test or t test. Subsample comparisons within the obsessive-compulsive disorder group were made using the chi-square test or Fisher’s exact test when necessary. These comparisons addressed possible differences related to gender and clinical characteristics (obsessions only versus compulsions or both and pure versus comorbid obsessive-compulsive disorder). Logistic regression was used to adjust associations between obsessive-compulsive disorder (compared with other neurotic disorders) and indicators of impaired quality of life for the total Clinical Interview Schedule score, excluding obsessive and compulsive symptoms. The aim was to clarify whether these associations were intrinsic features of the cardinal symptoms of obsessive-compulsive disorder or merely reflections of the overall severity of psychological morbidity. Further logistic regression models were deployed to adjust, for age and sex, associations of obsessive-compulsive disorder (compared with other neurotic disorders) with marital and occupational status. Associations between obsessive-compulsive disorder (relative to other neurotic disorders) and suicidal behaviors were similarly adjusted for the presence of depression, alcohol dependence, and the Clinical Interview Schedule score, excluding obsessive and compulsive symptoms.

Results

Prevalence

One hundred fourteen participants met ICD-10 criteria for obsessive-compulsive disorder, with a weighted prevalence of 1.1% (95% confidence interval [CI]=0.9%–1.3%). The female/male ratio was 1.44, a prevalence of 1.3% among women and 0.9% among men. Prevalence declined sharply with increasing age, from 1.4% among those aged 16–24, 1.2% aged 25–44, 1.1% aged 45–64, and 0.2% aged 65–74. Sixty-one (55%) participants were purely obsessive; 14 (11%) were purely compulsive; and 39 (34%) had both obsessions and compulsions, with no gender differences in this respect.

Sociodemographic Characteristics

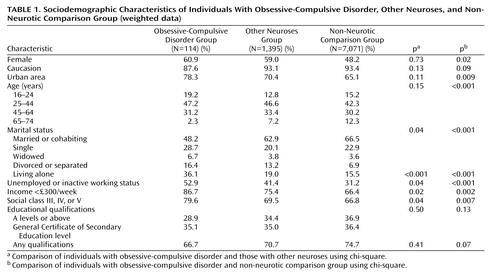

The sociodemographic characteristics of the sample are shown in Table 1 . Individuals with obsessive-compulsive disorder did not differ from the other two groups in ethnicity or educational qualifications. Relative to non-neurotic comparison individuals, obsessive-compulsive disorder participants were younger, more frequently female, and more likely to live in urban areas. Relative to comparison individuals and to those with other neuroses, participants with obsessive-compulsive disorder were more likely to be unemployed, of lower occupational social class, of lower income, and less likely to be married. The differences between those with obsessive-compulsive disorder and those with other neuroses were essentially unaltered after adjusting for age, gender, and the total Clinical Interview Schedule symptom score, excluding obsessive and compulsive symptoms.

Impairment

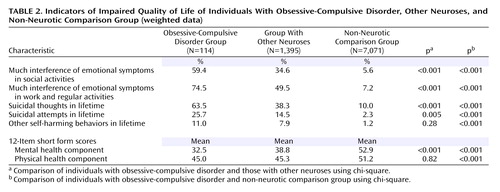

Indicators of impaired quality of life are summarized in Table 2 . With respect to interference of emotional symptoms in social activities, work and regular activities, and overall 12-item short form mental health component scores, obsessive-compulsive disorder individuals showed more impairment than both non-neurotic comparison individuals and individuals with other neurotic disorders. Relative to participants with other neuroses, participants with obsessive-compulsive disorder showed similar impairment on 12-item short form physical health component scores. The odds ratios comparing the odds of impairment in obsessive-compulsive disorder individuals versus individuals with other neuroses were 2.76 (95% CI=1.74–4.40) for social impairment and 2.98 (95% CI=1.73–5.13) for work impairment. These ratios were virtually identical (2.78 and 3.02, respectively) after adjusting for the effect of the Clinical Interview Schedule total score, excluding obsessive and compulsive symptoms. A self-reported lifetime history of suicidal acts was more common among the obsessive-compulsive disorder group relative to the comparison group and those with other neurotic disorders. The odds ratio for suicidal acts, when comparing the obsessive-compulsive disorder group with the neuroses disorder group, was 2.04 (95% CI=1.22–3.41). Adjusting for the presence of either depressive disorder (adjusted odds ratio=1.74, 95% CI=1.02–2.96), alcohol dependence (adjusted odds ratio=1.96, 95% CI=1.14–3.35), or total Clinical Interview Schedule score, excluding obsessive and compulsive symptoms (adjusted odds ratio=2.04, 95% CI=1.26–3.30), indicated that this association was unlikely to be accounted for by comorbidity.

Comorbidity With Other Psychiatric Disorders

Fifteen (12.7%) individuals with obsessive-compulsive disorder screened positive for possible psychosis (a Psychosis Screening Questionnaire score of 2 or more), and an additional four met other screening criteria. Thus, nineteen obsessive-compulsive disorder participants proceeded to the second phase assessment with the SCAN. Among these participants, three (15.8% of screen positives and 2.6% of all obsessive-compulsive disorder participants) met ICD-10 criteria for schizophrenia in the past year. All three had compulsions and obsessions; two were pure and one was comorbid with multiple neurotic disorders.

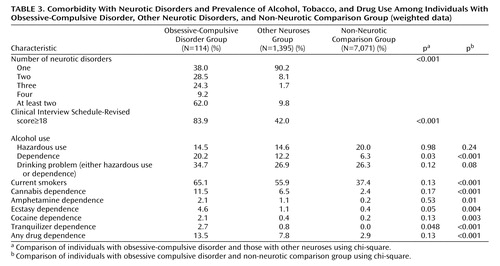

Seventy-six (62.0%) patients with obsessive-compulsive disorder had one or more comorbid neurosis, significantly more than the group with other neuroses (9.8%) ( Table 3 ). The overall severity of psychological morbidity was also greater for obsessive-compulsive disorder individuals (83.9% had a Clinical Interview Schedule score of 18 or greater compared with 42.0% of individuals with other neuroses [p<0.001]). The most frequent obsessive-compulsive disorder comorbidity was depressive episode (36.8%), followed by generalized anxiety disorder (31.4%), agoraphobia or panic disorder (22.1%), social phobia (17.3%), and specific phobia (15.1%). There were no significant gender differences in either overall comorbidity or the comorbid prevalence of individual neurotic disorders.

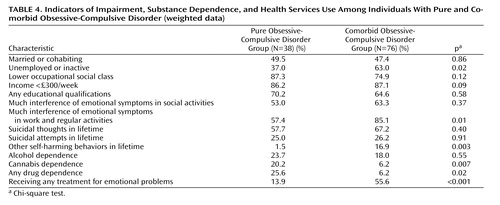

Despite the differences in overall levels of psychological morbidity, pure and comorbid obsessive-compulsive disorder individuals did not differ regarding the following proportions: currently married or cohabiting, occupational social class, income, or achievement of educational qualifications ( Table 4 ). Self-reported interference in social life and lifetime history of suicidal attempts were also similar. Participants with comorbid conditions were more frequently economically inactive and reported more interference in work and regular activities. However, the striking difference between pure and comorbid individuals was in their propensity for help-seeking, with 55.6% of comorbid participants but only 13.9% of pure participants receiving any treatment for emotional problems. This difference was not accounted for by the higher prevalence of substance dependence among those with pure obsessive-compulsive disorder; a stratified analysis (not reported) indicated that the association was equally apparent among those with and without alcohol or substance use dependence. Overall, individuals with obsessive-compulsive disorder were more likely to have been receiving treatment (39.8%) relative to those with other neuroses (22.7%, p<0.001) and to non-neurotic comparison participants (3.9%, p<0.001).

Alcohol and Substance Use

The overall prevalence of problem drinking (defined as hazardous use or alcohol dependence) did not differ significantly between the three groups ( Table 3 ). However, a higher proportion of problem drinkers among participants with obsessive-compulsive disorder showed features of alcohol dependence, and the prevalence of dependence among these was nearly four times higher than that of the non-neurotic comparison group and nearly twice that of those with other neuroses. No individuals with crack, glue, heroin, or methadone dependence were found in the obsessive-compulsive disorder group. However, smoking and dependence on cannabis, amphetamine, ecstasy, and cocaine were all significantly more common among those with obsessive-compulsive disorder than non-neurotic comparison participants. All forms of alcohol and substance use disorder were approximately three to four times more common in men than in women with obsessive-compulsive disorder (33.3% of men and 11.7% of women were alcohol dependent; 20.3% of men and 9.2% of women had a drug dependence). The exception was tranquilizer dependence, which was present in 3.3% of women and 1.7% of men with obsessive-compulsive disorder. The presence of comorbidity among obsessive-compulsive disorder individuals was not associated with alcohol use disorder, but dependence on any drugs (25.6% versus 6.2%, p=0.002), and on cannabis in particular (20.2% versus 6.2%, p=0.008), was more common among those with obsessive-compulsive disorder without comorbidity.

Discussion

In our community study, we analyzed data from a carefully conducted survey of a representative random sample of adults from all areas of Great Britain. The study does, however, have some limitations that must be highlighted. Only 114 participants with obsessive-compulsive disorder were identified, which lowered the power of some statistical analyses, especially those of subgroups of obsessive-compulsive disorder participants. The response rate of 69.5% suggests that the prevalence of the condition may have been underestimated, since those with obsessive-compulsive disorder might have been more likely to refuse. The use of lay interviewers and a fully structured clinical interview may, on the other hand, have led to overestimates of the presence and severity of obsessive-compulsive symptoms (2 , 20) . The validity of the obsessive-compulsive disorder ICD-10 diagnosis, as generated by the Clinical Interview Schedule, has not been established. Although agreement about the diagnosis of obsessive-compulsive disorder with the SCAN clinician semistructured assessment has been poor in general validations of the Clinical Interview Schedule, the numbers of obsessive-compulsive disorder individuals were inadequate to draw robust conclusions (21) . Psychotic disorders were fully assessed in a second phase of the survey and only for a stratified subsample of participants. Only three participants with obsessive-compulsive disorder were thus identified as suffering from schizophrenia; since it could not be determined whether these were comorbid or misclassified and the numbers were too small substantially to affect our findings, these three participants were retained in the analysis. The study did not include eating and somatoform disorders. The cross-sectional design only provides information about the present state and does not allow inferences on lifetime psychopathology.

Our general findings are consistent with the available epidemiological data on obsessive-compulsive disorder (7 – 9 , 22) . The weighted prevalence of 1.1% is similar to most previous studies in different countries. Seven international studies using the Diagnostic Interview Schedule (9) show annual prevalence ranging from 1.1% to 1.8%, and recent studies from Great Britain (16) , Canada (2) , and Chile (22) report current prevalence varying from 1.1% to 1.3%.

The data presented in this study are also in agreement with most epidemiological studies pointing to a predominance of obsessive-compulsive disorder in lower age groups (8) and in women (7 , 9) . In the previous British survey (16) , obsessive-compulsive disorder was diagnosed in 1.5% of women and 1.0% of men. An equal prevalence in both sexes was found in the Edmonton study (23) , while summarized data from international studies (9) showed a female/male ratio varying from 1.2 to 1.8. Our findings also reinforce the predominance of individuals with pure obsessions in the community (8 , 9 , 23) . By contrast, in clinical samples, the sex ratio tends to be equal (24) , and the majority of individuals have both obsessions and compulsions (4) . This may reflect differences in assessment methods or in the types of individuals that reach health care; presumably, women and the purely obsessive individuals are less likely to seek treatment (4) .

Our data do not confirm the reported rarity of obsessive-compulsive disorder in ethnic minority groups in the community (4 , 7 , 8) but are in line with those that show similar educational qualifications (4) and lower rates of marriage (8) .

Obsessive-compulsive disorder participants had relatively high rates of comorbidity, a finding that is in accordance with most data from both community (8 , 16 , 23) and clinical settings (25 , 26) . While our comparison was of necessity skewed (those with obsessive-compulsive disorder and one or more other neurotic disorders were counted only once as being comorbid obsessive-compulsive but not as comorbid with other neurosis), this could not have accounted for more than a small part of the large difference in comorbidity between those with obsessive-compulsive disorder and those with other neuroses. The most frequent comorbid condition was depressive episode, followed by anxiety disorders (25 – 29) . Direct comparison with other studies is complicated, since most are from clinical settings and several use different diagnostic categories. However, our findings are in the reported range for depressive episode (20%–67%), simple phobia (7%–22%), social phobia (8%–42%), and generalized anxiety disorder (8%–32%) (24 – 26 , 28 , 30 – 33) . The 34% prevalence of problem drinking (hazardous drinking or dependence) among obsessive-compulsive disorder individuals is similar to the 36% described in Canada (23) but higher than the 24% found in the Epidemiological Catchment Area Study (8) . This higher rate may be because of measurement or cultural differences, since the prevalence of problem drinking in our non-neurotic comparison group was as high as 26%. Dependence may be a specific problem for obsessive-compulsive disorder sufferers, since they differed in this aspect (but not in hazardous drinking) from the other two groups. The lower rates of alcohol dependence (approximately 10%) described in clinical samples (34 – 36) may suggest that individuals with obsessive-compulsive disorder and alcohol dependence are either less likely to seek treatment or are being treated for their alcohol problem, with their obsessive-compulsive disorder going unrecognized (37) . More obsessive-compulsive disorder participants were current smokers (65%) than non-neurotic individuals (37%), contradicting previous reports of low rate tobacco use (29 , 38) . Interestingly, pure obsessive-compulsive disorder individuals had significantly higher rates of dependence on drugs (particularly on cannabis) than comorbid individuals, lending support to the notion that some sufferers may use substances as an attempt to deal with the distress caused by the obsessions or compulsions rather than seeking professional attention (8 , 23) . As expected, both alcohol hazardous use and dependence were significantly more common in men (32) , and all kinds of drug dependence were more frequent in men, although many of the differences did not reach statistical significance.

Our analysis highlights the public health significance of obsessive-compulsive disorder. Although it is a relatively rare condition, it is associated with a very high degree of impairment. Individuals with obsessive-compulsive disorder stand out not only from those who are mentally well but also from those with other neurotic conditions. With respect to those individuals with other neuroses, individuals with obsessive-compulsive disorder are less likely to be married, more likely to be unemployed, more likely to have very low income levels, and more likely to have low occupational status. They are also more likely to report impaired social and occupational functioning. These differences are largely independent of the extent of non-obsessive-compulsive-disorder-related psychological morbidity, suggesting an intrinsic effect of obsessive and compulsive symptoms. An important finding in our study is that 26% of the obsessive-compulsive disorder participants reported at least one suicidal attempt in their lifetime, nearly double the proportion among those with other neuroses, and 10 times that of non-neurotic comparison individuals. Historically, and perhaps erroneously, patients with obsessive-compulsive disorder have been considered at low risk for suicide (39 , 40) , with the exception of a few studies (33 , 41) . Our data suggest that obsessive-compulsive disorder does not fit conveniently into the fashionable relabeling of neurosis as “common mental disorder” and psychosis as “severe mental illness.” Obsessive-compulsive disorder is a neurosis that is both rare and severe and should be prioritized accordingly.

Encouragingly, perhaps because of the chronicity and severity of the disorder, rates of help-seeking and engagement with treatment are relatively high among obsessive-compulsive disorder individuals overall. However, even with similar degrees of psychosocial impairment and suicidal risk and more drug dependency, pure obsessive-compulsive disorder individuals are receiving much less treatment than those with comorbidity (14% versus 56%). This is a clear indication of unmet need and a cause for concern. More research is warranted to identify the barriers to seeking and receiving help in this subgroup. These may include the egodystonic nature of obsessive-compulsive disorder symptoms and the low level of public awareness about the existence or nature of the condition, compared, for example, with that which exists for depression, phobia, or psychosis. An appropriate public health response may need to combine public education with training of professionals, particularly primary health care workers.

1. Jenkins R: Making psychiatric epidemiology useful: the contribution of epidemiology to government policy. Int Rev Psychiatry 2003; 15:188–200Google Scholar

2. Stein MB, Forde DR, Anderson G, Walker JR: Obsessive-compulsive disorder in the community: an epidemiologic survey with clinical reappraisal. Am J Psychiatry 1997; 154:1120–1126Google Scholar

3. Welkowitz LA, Struening EL, Pittman J, Guardino M, Welkowitz J: Obsessive-compulsive disorder and comorbid anxiety problems in a national anxiety screening sample. J Anxiety Disord 2000; 14:471–482Google Scholar

4. Samuels J, Nestadt G: Epidemiology and genetics of obsessive-compulsive disorder. Int Rev Psychiatry 1997; 9:61–71Google Scholar

5. Horwath E, Weissman MM: The epidemiology and cross-national presentation of obsessive-compulsive disorder. Psychiatr Clin North Am 2000; 23:493–507Google Scholar

6. Kessler RC, McGonagle KA, Zhao S, Nelson CB, Hughes M, Eshleman S, Wittchen HU, Kendler KS: Lifetime and 12-month prevalence of DSM-III-R psychiatric disorders in the United States: results from the National Comorbidity Survey. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1994; 51:8–19Google Scholar

7. Bebbington PE: Epidemiology of obsessive-compulsive disorder. Br J Psychiatry Suppl 1998; 35:2–6Google Scholar

8. Karno M, Golding JM, Sorenson SB, Burnam MA: The epidemiology of obsessive-compulsive disorder in five US communities. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1988; 45:1094–1099Google Scholar

9. Weissman MM, Bland RC, Canino GJ, Greenwald S, Hwu HG, Lee CK, Newman SC, Oakley-Browne MA, Rubio-Stipec M, Wickramaratne PJ, Wittchen H, Yeh EK (Cross National Collaborative Group): The cross national epidemiology of obsessive compulsive disorder. J Clin Psychiatry 1994; 55(suppl):5–10Google Scholar

10. Singleton N, Bumpstead R, O’Brien M, Lee A, Meltzer H: Psychiatric Morbidity Among Adults Living in Private Households, 2000: Summary Report: the Report of a Survey Carried Out by Social Survey Division of the Department of Health, the Scottish Executive and the National Assembly for Wales. London, 2001Google Scholar

11. Singleton N, Bumpstead R, O’Brien M, Lee A, Meltzer H: Psychiatric morbidity among adults living in private households, 2000. Int Rev Psychiatry 2003; 15:65–73Google Scholar

12. Kish L: Survey Sampling. London, John Wiley and Sons, 1965Google Scholar

13. Lewis G, Pelosi AJ: Manual of the Revised Clinical Interview Schedule (CIS-R). London, Institute of Psychiatry, 1990Google Scholar

14. Lewis G, Pelosi AJ, Araya R, Dunn G: Measuring psychiatric disorder in the community: a standardized assessment for use by lay interviewers. Psychol Med 1992; 22:465–486Google Scholar

15. World Health Organization: The ICD-10 Classification of Mental and Behavioural Disorders: Diagnostic Criteria for Research. Geneva, World Health Organization, 1993Google Scholar

16. Meltzer H, Gill B, Petticrew M, Hinds K: The Prevalence of Psychiatric Morbidity Among Adults Living in Private Households. London, Her Majesty’s Stationery Office, 1995Google Scholar

17. Babor TF, de la Fuente JR, Saunders J, Grant M: AUDIT: The Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test: Guidelines for Use in Primary Health Care. Geneva, World Health Organization, 1992Google Scholar

18. Stockwell T, Murphy D, Hodgson R: The Severity of Alcohol Dependence Questionnaire: its use, reliability and validity. Br Acta 1983; 78:145–155Google Scholar

19. Stata Statistical Software Release 8.0. College Station, Tex, Stata Corp, 2003Google Scholar

20. Grabe HJ, Meyer C, Hapke U, Rumpf HJ, Freyberger HJ, Dilling H, John U: Prevalence, quality of life and psychosocial function in obsessive-compulsive disorder and subclinical obsessive-compulsive disorder in northern Germany. Eur Arch Psychiatry Clin Neurosci 2000; 250:262–268Google Scholar

21. Brugha TS, Bebbington PE, Jenkins R, Meltzer H, Taub NA, Janas M, Vernon J: Cross validation of a general population survey diagnostic interview: a comparison of CIS-R with scan ICD-10 diagnostic categories. Psychol Med 1999; 29:1029–1042Google Scholar

22. Araya R, Rojas G, Fritsch R, Acuna J, Lewis G: Common mental disorders in Santiago, Chile: prevalence and socio-demographic correlates. Br J Psychiatry 2001; 178:228–233Google Scholar

23. Kolada JL, Bland RC, Newman SC: Epidemiology of psychiatric disorders in Edmonton: obsessive-compulsive disorder. Acta Psychiatr Scand Suppl 1994; 376:24–35Google Scholar

24. Attiullah N, Eisen JL, Rasmussen SA: Clinical features of obsessive-compulsive disorder. Psychiatr Clin North Am 2000; 23:469–491Google Scholar

25. Steketee G, Chambless DL, Tran GQ: Effects of axis I and II comorbidity on behavior therapy outcome for obsessive-compulsive disorder and agoraphobia. Compr Psychiatry 2001; 42:76–86Google Scholar

26. Tukel R, Polat A, Ozdemir O, Aksut D, Turksoy N: Comorbid conditions in obsessive-compulsive disorder. Compr Psychiatry 2002; 43:204–209Google Scholar

27. Fireman B, Koran LM, Leventhal JL, Jacobson A: The prevalence of clinically recognized obsessive-compulsive disorder in a large health maintenance organization. Am J Psychiatry 2001; 158:1904–1910Google Scholar

28. Rasmussen SA, Eisen JL: The epidemiology and clinical features of obsessive compulsive disorder. Psychiatr Clin North Am 1992; 15:743–758Google Scholar

29. Degonda M, Wyss M, Angst J: The Zurich study, XVIII: obsessive-compulsive disorders and syndromes in the general population. Eur Arch Psychiatry Clin Neurosci 1993; 243:16–22Google Scholar

30. Milanfranchi A, Marazziti D, Pfanner C, Presta S, Lensi P, Ravagli S, Cassano GB: Comorbidity in obsessive-compulsive disorder: focus on depression. Eur Psychiatry 1995; 10:379–382Google Scholar

31. Crino RD, Andrews G: Obsessive-compulsive disorder and axis I comorbidity. J Anxiety Disord 1996; 10:37–46Google Scholar

32. Sobin C, Blundell M, Weiller F, Gavigan C, Haiman C, Karayiorgou M: Phenotypic characteristics of obsessive-compulsive disorder ascertained in adulthood. J Psychiatr Res 1999; 33:265–273Google Scholar

33. Hollander E, Greenwald S, Neville D, Johnson J, Hornig CD, Weissman MM: Uncomplicated and comorbid obsessive-compulsive disorder in an epidemiologic sample. Depress Anxiety 1996; 4:111–119Google Scholar

34. Riemann BC, McNally RJ, Cox WM: The comorbidity of obsessive-compulsive disorder and alcoholism. J Anxiety Disord 1992; 6:105–110Google Scholar

35. Rasmussen SA, Eisen JL: The epidemiology and differential diagnosis of obsessive compulsive disorder. J Clin Psychiatry 55(suppl 4):5–10, 1994Google Scholar

36. Yaryura-Tobias JA, Grunes MS, Todaro J, McKay D, Neziroglu FA, Stockman R: Nosological insertion of axis I disorders in the etiology of obsessive-compulsive disorder. J Anxiety Disord 2000; 14:19–30Google Scholar

37. Fals-Stewart W, Angarano K: Obsessive-compulsive disorder among patients entering substance abuse treatment: prevalence and accuracy of diagnosis. J Nerv Ment Dis 1994; 182:715–719Google Scholar

38. Bejerot S, Humble M: Low prevalence of smoking among patients with obsessive-compulsive disorder. Compr Psychiatry 1999; 40:268–272Google Scholar

39. Goodwin DW, Guze SB, Robins E: Follow-up studies in obsessional neurosis. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1969; 20:182–187Google Scholar

40. Koran LM, Thienemann ML, Davenport R: Quality of life for patients with obsessive-compulsive disorder. Am J Psychiatry 1996; 153:783–788Google Scholar

41. Hollander E, Stein DJ, Kwon JH, Rowland C, Wong CM, Broatch J, Himelein C: Psychosocial function and economic costs of obsessive-compulsive disorder. CNS Spectr 1998; 3(suppl): 48–58Google Scholar