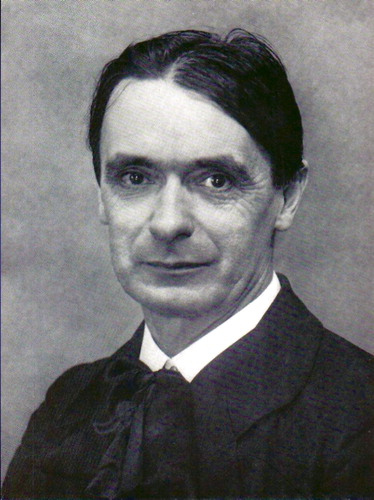

Rudolf Steiner (1861–1925)

In the aftermath of World War I, Rudolf Steiner became a household name in Europe. This charismatic, prophetic, and iconoclastic figure brought about an entire movement for spiritual renewal (1) . Steiner gave rise to new impulses in agriculture, architecture, art, education (Waldorf schools), religion, and medicine. He named his movement “anthroposophy,” a term taken from the 19th-century Swiss philosopher and physician Ignaz Troxler.

A worldwide anthroposophical movement now exists to include a medical school, community hospitals, and pharmaceutical companies. The literature does not yet allow judgment regarding the efficacy of anthroposophical medicine (2 , 3) .

Steiner’s insights have also been applied to psychiatry, where a variety of treatments are used, targeted at the human being’s spiritual, psychological, and physical elements (4) . Examples of spiritually directed treatments include meditation, morning preview of what the day will bring, and evening retrospect of the day. Psychologically directed treatments include art, music, and therapeutic eurythmy. Physical interventions range from metal therapy to homeopathic remedies. In treating traumatic bereavement, for example, silver is often used; for obsessive-compulsive disorder, mercury is used. Mistletoe, which is used to treat cancer, also has a place in the treatment of schizophrenia (4) .

Early in the 20th century, Steiner observed that most so-called mental illnesses were based on either organ or nutritional dysfunction, while much of what we consider organic illness was strongly rooted in dysfunction of the life of the soul (psyche).

For many, Steiner’s writings stretch credibility. Yet in a world beset by so many challenges, what he has to say may bear consideration, including his insights on the spiritual-mental-physical constitution of the human being and on how mental illness can be treated.

1. Storr A: Feet of Clay. London, Harper Collins, 1997Google Scholar

2. Alm JS, Swartz J, Lilija G, Scheynius A, Pershagen G: Atopy in children of families with an anthroposophic lifestyle. Lancet 1999; 353:1485–1488Google Scholar

3. Ernst E: Anthroposophical medicine: systematic review of randomized clinical trials. Wien Med Wochenschsift 2004; 116:128–130Google Scholar

4. Husemann F, Wolff O: The Anthroposophical Approach to Medicine: Psychiatry. Hudson, NY, Anthroposophical Press, 1989Google Scholar