Treatment Outcome and Physician-Patient Communication in Primary Care Patients With Chronic, Recurrent Depression

Abstract

OBJECTIVE: The authors’ goal was to assess the adequacy of control, quality of life, and treatment experiences of patients with chronic, recurrent depression being treated by primary care physicians. METHOD: The sample comprised 1,001 patients 18 years old or older who had chronic, recurring depression and were currently being treated with a single antidepressant prescribed by a primary care physician. These patients had responded positively to questions regarding the presence of clinical depression and prescription of a single antidepressant by a primary care physician during a telephone survey conducted in two stages separated by 18 to 24 months. The 1,001 patients participated in a structured, 20-minute, anonymous interview conducted by trained personnel. RESULTS: Most patients had recurrent depression (median=5 episodes), and most had taken their current antidepressant for more than 1 year. The mean age at onset of depression was 33.8 years, and the mean age at time of diagnosis was 38.0 years, with treatment following a mean of 2 years later. Most patients were satisfied with the care they received from their primary care physician, but many also reported incomplete symptom resolution and substantial side effects from medications that were not discussed with or by their primary care physician. A majority of patients reported that treatment decisions were made in conjunction with their physician, a method that was preferred by three-quarters of the group. Although 752 patients reported that they had mild or moderate depression, 729 were satisfied with their life and 600 said they were in good or excellent health. CONCLUSIONS: Despite being mostly satisfied with the care received from their primary care physician, patients with chronic, recurring depression had substantial levels of continuing dysfunction, distress, unrelieved symptoms, and medication side effects, which suggests several possible physician-centered, patient-centered, or system-centered barriers to treatment to full function and wellness.

Major depression is common, costly, and most often diagnosed and treated in primary care settings rather than in specialty mental health care settings (1, 2). In a national probability survey of U.S. adults (3), 10.3% of more than 8,000 respondents had experienced a depressive episode in the past year and 17.1% had a lifetime history of major depression. Major depression is the leading cause of disability worldwide and exceeds the second-place cause (ischemic heart disease) by a particularly large margin in women (4). In a recent Institute of Medicine report (5), more effective care of depression was listed as one of the major unmet health care priorities in the United States.

Effective pharmacologic treatments for depression have been available for more than 40 years. Because of recent improvements in the efficacy, safety, and tolerability of antidepressants (6), depression is increasingly being diagnosed and treated in the primary care setting. Depression in primary care can be severe, chronic, and recurrent, as well as complicated in its course and presentation (7–9). For these reasons, despite government reports (10), treatment guidelines (11–13), consensus statements (14, 15), and a large body of clinical research (16), depression remains underrecognized and undertreated (17–19). Although the accuracy of diagnosis by primary care physicians may be improving, particularly in patients who are more severely afflicted (7), undertreatment is less well understood and explored. Important concerns remain about treatment to remission, and there is a need to better understand maintenance treatment in primary care (17).

This report describes the findings of a national survey of primary care patients who were selected specifically for chronic and recurrent depression. The study, conducted under the sponsorship of the Depression and Bipolar Support Alliance (formerly the National Depressive and Manic-Depressive Association), which is the nation’s largest patient-directed, illness-specific organization, was designed to determine the effect of chronic, recurrent depression on patients’ lives and to assess patients’ experience and satisfaction with primary care treatment, particularly the likelihood of being treated to wellness and the barriers to achieving full remission.

Method

Sampling Methods

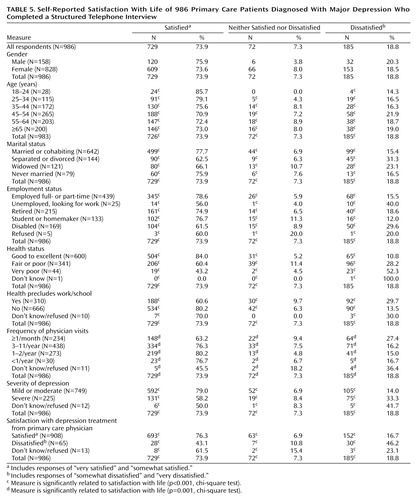

The patient sample was constructed from a two-stage national probability sample by a national independent health care research organization (Schulman, Ronca, & Bucuvalas, Inc., Silver Spring, Md.). Telephone numbers for potential survey participants were randomly identified from an ongoing monthly national survey that is mailed to households across the United States for the purposes of measuring general health characteristics. From this national household probability sample, a telephone survey was conducted to develop a database of households in which at least one adult (18 years old or older) reported a diagnosis of clinical depression and receipt of antidepressant medication from a primary care physician. A total of 12,316 households were randomly selected from this database and assessed with a second telephone interview conducted 18 to 24 months later. Trained telephone interviewers asked five screening questions to identify individuals in the household who had been diagnosed with major depression and who were currently being treated with one antidepressant prescribed by a primary care physician. Of the 7,785 households that were reached (Figure 1), 5,871 respondents completed the screen; 2,953 of these respondents had no current diagnosis of depression. Of the 2,918 with depression, 585 had received a diagnosis such as bipolar disorder (N=252), mania (N=315), or schizophrenia (N=18); 1,332 were not being treated with only a single antidepressant prescribed by a primary care physician (i.e., they had not taken an antidepressant in the previous 12 months [N=144], were not currently taking an antidepressant [N=131], were taking more complex antidepressant regimens [N=342], received an antidepressant from a psychiatrist [N=678], or did not complete the telephone interview [N=37]).

These exclusions left a sample of 1,001 respondents who were depressed at two points in time 18 to 24 months apart and who were taking a single antidepressant prescribed by a primary care physician. These 1,001 respondents completed a 20-minute structured telephone interview. All responses were entirely anonymous.

Instrument Development

Telephone interview questions were based on standardized clinical assessments of patient experiences, satisfaction with care, unresolved symptoms, and experience with side effects. The assessment was developed in consultation with depression experts and was not otherwise pilot-tested or validated. The patient telephone interview included 10 demographic items and 60 items covering current and lifetime health status, treatment of depression, and health insurance status, organized as closed yes/no questions, categorical questions, and 4- and 5-point Likert scales. Open-ended questions provided additional opportunities for respondents to expand their answers. Data were collected between May 9, 2000, and June 15, 2000. All data were collected entirely anonymously, and the anonymous secondary analysis of the data set was given a human subjects exemption by the Institutional Review Board of the University of Michigan.

Data Analysis

Data were computerized and analyzed by Schulman, Ronca, & Bucuvalas, Inc., with the Statistical Package for Social Sciences. We also conducted additional statistical analysis. Results are reported primarily as simple descriptive summary data and cross-tabulation correlations with respondent characteristics, severity of depression, and satisfaction with care. Pearson chi-square tests were performed to determine the presence of statistically significant relationships between life satisfaction, control of depression, and demographic variables, respectively.

Results

Patients

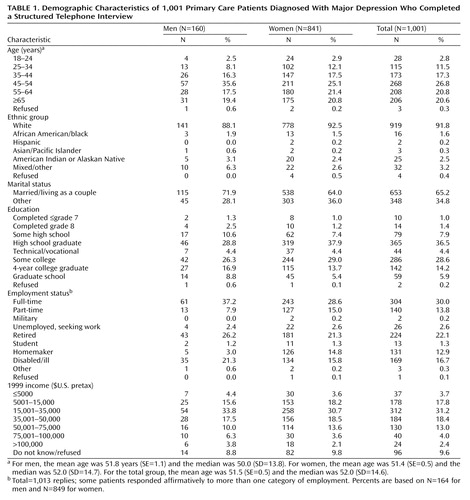

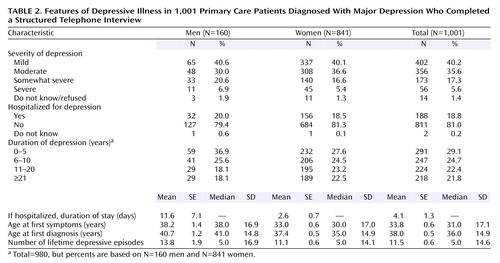

Demographic characteristics of the 1,001 patients who completed the full interview are shown in Table 1. The mean age of the sample was 51.5 years (SE=0.5, range=18–97). The sample was predominantly female, Caucasian, and married or living as a couple and had at least a high school diploma or technical or vocational training. The mean age at which patients experienced depressive symptoms was 33.8 years, but the mean age at the time of first diagnosis was 4.2 years later, at 38.0 years of age (Table 2). The mean time between age at first symptoms and diagnosis of depression was longer for women (4.4 years) than men (2.5 years). Most patients (73.0%) experienced more than one depressive episode in their lifetime; the mean number of episodes was 11.5, although the median was only five episodes (Table 2). The mean age at which patients started antidepressant treatment was 39.8 years (42.3 years for men and 39.3 years for women), or a mean of nearly 2 years after diagnosis and 6 years after onset of symptoms.

Treatment History and Decisions

In most instances (90.7%), a family physician, general practitioner, or internal medicine specialist prescribed the antidepressant; for the remainder a nurse practitioner or other nonpsychiatrist physician prescribed the antidepressant. Most patients had taken their current antidepressant for more than 1 year (20.3% for 1 to 2 years, 22.9% for 3 to 5 years, 10.7% for 6 to 9 years, and 15.0% for 10 or more years), reflecting the chronic and recurring nature of the depression in this sample and the fact that most patients were receiving maintenance antidepressant treatment. The remaining patients had been taking their current antidepressant for less than 1 year. Most patients (86.2%) expected to receive antidepressant therapy for an extended period of time.

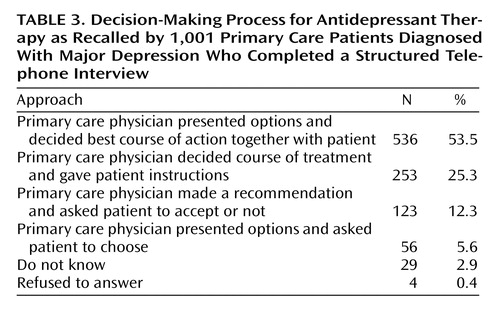

When asked to describe how treatment decisions about their depression were made, approximately half of the patients said that their primary care physician discussed options and they decided the best course of action together (Table 3). Fifty-six patients reported that their physician presented all available alternatives and asked them to choose one, about one-quarter reported that their primary care physician decided the best course of action and provided it to them with instructions, and 123 reported that the physician presented recommendations and asked them to decide whether to accept them (Table 3). Thus, more than one-third of the patients experienced a directive approach by their primary care physician, who retained most of the control over the treatment planning. More than two-thirds of patients (70.2%) reported that they would prefer to discuss all options and decide the best plan of action jointly with their physician. Overall, the physicians of approximately one-quarter of the patients used a treatment decision strategy that was not the one preferred by that particular patient.

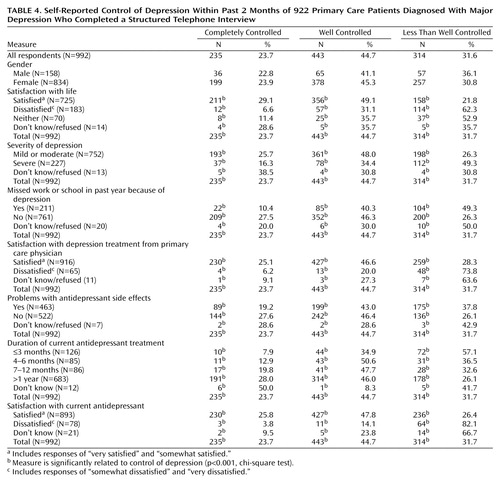

Treatment Satisfaction

Despite the fact that a majority of patients felt satisfied with their medical care, felt adequately informed about their treatment, and were relatively satisfied with their life, a majority also felt that their depression had not been completely controlled during the previous 2 months (Table 4). Although 31.6% of the patients said that their depression was less than well controlled, most of this subset (25.4% of the entire group) described their depression as somewhat controlled, and only 6.2% said their depression was poorly controlled or not at all controlled. Only 23.7% reported that their depression was completely controlled. The patients’ sense that their depression was controlled corresponded with higher satisfaction with current treatment. For example, 657 (96.9%) of the 678 patients who reported that their depression was completely or well controlled were satisfied with their treatment, but 48 (73.8%) of the 65 patients who were dissatisfied with their treatment believed that their depression was less than well controlled (Table 4).

Satisfaction With Primary Care Physician

A minority of patients (15.6%) reported changing primary care physicians because of dissatisfaction with the treatment of their depression. Approximately 65% of patients considered their physician’s knowledge of depression and its treatment to be excellent (31.7%) or very good (32.8%). A majority of patients rated their physicians as excellent or very good with regard to their ability to encourage questions or express concerns (71.1%) and ability to answer questions (77.0%).

Quality of Life

A majority of patients reported being very or somewhat satisfied with their life and reported their overall health as excellent, very good, or good, despite the fact that most patients reported the current severity of their depression as mild or moderate (Table 2). Most of the respondents (81.0%) had never been hospitalized for depression. However, for the 188 patients who had been hospitalized, the mean duration of hospitalization was 4.1 days (Table 2). Most patients (76.5%) did not miss work or school because of depression during the previous 12 months, but those who did were absent for an average of 97.7 days (mean=168.7 days for men; mean=80.3 days for women).

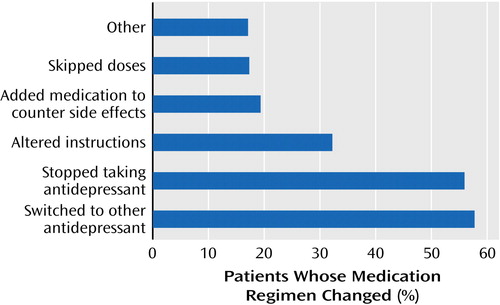

The relationships between general demographic and health-related factors and either satisfaction with life (Table 5) or self-reported ratings of depression control (Table 4) were assessed. Marital status (χ2=24.45, df=6, p<0.001) and employment status (χ2=33.53, df=8, p<0.001) correlated significantly with life satisfaction (Table 5). A substantial minority of those who were separated or divorced or out of work and looking for employment were dissatisfied with their life (Table 5). Patients who described their health as very poor (χ2=101.26, df=6, p<0.001) or their depression as severe (χ2=45.56, df=2, p<0.001) also were more dissatisfied with their lives, as were patients who were more dissatisfied with the depression care received from their primary care physicians (χ2=38.34, df=2, p<0.001).

Several factors appear to relate to patient self-reports of how well their depression was controlled (Table 4). Less well controlled depression was significantly related to greater depression severity (χ2=42.90, df=2, p<0.001), dissatisfaction with depression treatment received from the primary care physician (χ2=59.00, df=2, p<0.001), and dissatisfaction with the current antidepressant (χ2=104.26, df=2, p<0.001). A majority of patients who rated their depression as completely or well controlled had mild to moderate depression, had not missed school or work in the past year because of their depression, or did not report problems with antidepressant side effects (Table 4).

The duration of antidepressant treatment correlated with patients’ perceptions of the degree to which their depression was controlled (χ2=60.53, df=6, p<0.001). Among those patients who had been treated with antidepressants for 3 months or less, 57.1% believed their depression to be less than well-controlled (Table 4). In contrast, 73.9% of the patients who had received long-term antidepressant treatment (i.e., >1 year) rated their depression as either completely or well controlled (Table 4).

Side Effects

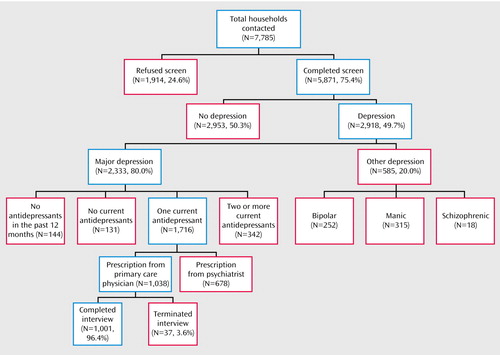

A majority of the 1,001 patients (61.6%) recalled that their doctor discussed the possibility of antidepressant side effects before prescribing treatment. The most common side effects that patients remembered their physicians discussing in advance were fatigue (N=134 [21.7%]), insomnia (N=119 [19.3%]), nausea/vomiting (N=115 [18.6%]), weight gain (N=101 [16.4%]), sexual problems (N=99 [16.0%]), and headache (N=97 [15.7%]) (Figure 2). Slightly more than half of the 1,001 patients (57.8%) reported that their physician did not inquire about their preferences or willingness to tolerate certain side effects before prescribing therapy. During the course of their depressive episode(s), 61.0% of the 1,001 patients switched from one antidepressant to another. The most common reasons cited by patients for switching antidepressants were lack of efficacy (N=247 [40.4%]) and side effects (N=222 [36.3%]).

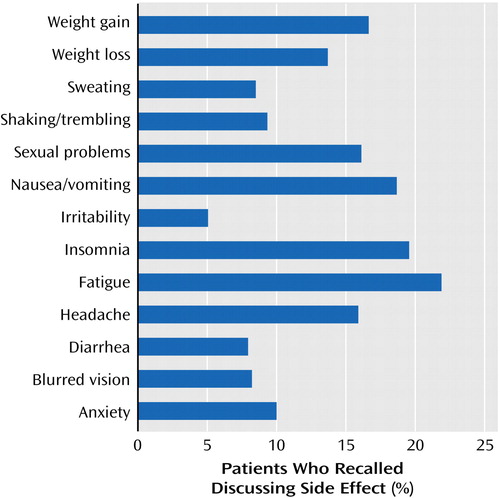

When asked if they experienced problems with side effects from any of the antidepressants that they had taken, 466 of the 1,001 respondents answered in the affirmative. Fatigue (N=208 [44.6%]), sexual problems (N=179 [38.4%]), insomnia (N=171 [36.7%]), weight gain (N=158 [33.9%]), and anxiety (N=154 [33.0%]) were the most commonly reported side effects. Among this subset of 466 patients, 267 (57.3%) switched to another antidepressant and 258 (55.4%) stopped taking the antidepressant because of side effects. These respondents also reported that antidepressant side effects caused them to change the way they took a prescribed antidepressant (N=148 [31.8%]), led their physician to add another medication to counter the side effects (N=91 [19.5%]), or caused them to skip doses of the prescribed antidepressant (N=81 [17.4%]) (Figure 3). A majority of the 466 patients (N=421 [90.3%]) reported telling their primary care physician about these side effects, either at the next scheduled office visit (N=168 [39.9%]), by telephone when the side effect occurred (N=145 [34.4%]), or at a special interim visit necessitated by the side effect (N=85 [20.2%]).

Adherence to Prescribed Treatment

During the current or most recent antidepressant treatment period, most patients (74.8%) claimed that they took the prescribed dose as instructed. A total of 359 of the 1,001 patients missed at least one dose per week simply because they forgot to take their medication. Patients who stopped taking their antidepressant altogether (N=534) reported doing so because of financial issues (N=154 [28.8%]), side effects (N=86 [16.1%]), and/or because they felt better (N=143 [26.8%]).

Discussion

To our knowledge, this is the first study to assess the experiences of clinically depressed patients with a high level of chronicity and recurrence who were being treated by primary care physicians. Our main findings are that these patients were not being treated to full remission, complete wellness, and full function. Despite this less than optimum clinical outcome, patients had a relatively high level of satisfaction with the care received from their primary care physicians. Patient satisfaction with their physician may be related to the enduring commitment primary care physicians make to their patients’ care, despite a lack of complete response. Moreover, patients may perceive that the barriers to full recovery are not physician specific, and they may be more accepting of incomplete resolution of depression than for other illnesses. What is unclear and bears further study is which specific barriers are amenable to improvement, whether the proportion of nonremitting patients is larger than the proportion in other chronic illnesses, and the degree to which these barriers are physician centered, patient centered, or system centered.

There are many known physician- and patient-specific barriers to depressed patients’ achieving full symptom resolution (14, 16, 20–23). Patients may experience incomplete response because of inadequate treatment strategies, poor adherence to the prescribed regimen, or inadequate patient education about the therapeutic plan, particularly the need for monitoring therapeutic response and adjusting the medication regimen. All of these barriers are likely interrelated and may stem from inadequate communication between the primary care physician and the depressed patient.

The patients in this study had a high level of education, were primarily Caucasian, had ready access to medical care, and were in active treatment with a primary care physician at the time the survey was conducted. Despite these advantages, which are not enjoyed by more general patient populations, there was a mean gap of more than 4 years between the age at which the patients reported first experiencing depressive symptoms and the age at which they received a diagnosis. We could not determine whether patients did not seek medical attention when they became symptomatic or did seek treatment but were not diagnosed properly. It is not uncommon for depressed patients to seek general medical care frequently and persistently; usually they receive extensive medical evaluations and testing without definitive results or an accurate depression diagnosis (24–26).

The mean age at which antidepressants were prescribed was 39.8 years, nearly 2 years after diagnosis, suggesting a possible focus on psychotherapy or watchful waiting after the initial diagnosis was made, although our study was not designed to assess referral for psychotherapy. On average, a 6-year gap existed between the time of symptom onset and the time that antidepressant medication was initiated in this group of patients. We could not determine whether medication was indicated during that interval or how care was provided during that time. It is clear, however, that considerable time elapsed from the time of symptom onset to the initiation of medication, with an increasing level of morbidity, dysfunction, and the possibility of greater risk of chronicity and recurrence. We do not know if there were clues that would have helped the physician shorten this delay, but this topic is worthy of future exploration.

Approximately half of the patients reported having difficulties with antidepressant side effects. One out of four patients was not adherent to the prescribed antidepressant regimen. The cost of antidepressant treatment, lack of insurance coverage, side effects, or resolution of depressive symptoms were the most commonly cited reasons that patients elected to stop taking their medication.

Several aspects of physician-patient communication may be amenable to improvement. Many patients desire more active communication about side effects, a patient-centered and collaborative style of communication and treatment planning, and a shared commitment to achieving wellness and full symptom resolution. A team-building approach, which includes strong patient-physician relationships and shared decision making, has been shown to increase adherence and treatment outcomes (5, 27–30). Likewise, patients who received specific educational messages about how to take their medication (e.g., “The medication is intended to be taken for several months before we discuss stopping it,” “Do not stop just because you feel better,” “Take it for at least 4 weeks before assessing side effects”) and information about how to obtain answers to their questions are more likely to adhere to the treatment plan (31).

According to our findings, an important area in which communication could be improved is the way in which treatment decisions are made. Nearly 60% of the patients thought that treatment decisions were made jointly, and indeed this approach was preferred by nearly three-quarters of the patients. More than one-third of the group reported that a treatment course was selected for them and instructions provided. Patients who disagree with the choice of antidepressant that is prescribed by their primary care physician or who experience significant or unanticipated side effects are less compliant with their medication regimen (31) and thus may not experience full symptom resolution. In this study, more than one-third of respondents said that side effects made them switch to a different antidepressant, and one-sixth said that side effects made them change the way they took their medicine. Our findings agree with several reports in which nearly half of depressed patients stopped or changed the way they took their antidepressant medication because of side effects (31–35).

The usual limitations of retrospective and self-report telephone surveys restrict the generalizability of our findings to other groups of primary care patients. The sample included few minority respondents, which is not uncommon in national telephone surveys (36). The sample, by design, included only those patients who had been depressed and used antidepressants for at least 18 months, thus introducing selection bias by excluding patients who had discontinued treatment and who may have been dissatisfied with elements of their treatment. Consistent with the findings from a large, national epidemiologic study, our sample of patients with depression was predominantly female, and their first depressive episode occurred in the third decade of life (3, 37).

Recall bias is a significant source of error in interpreting the results, particularly with regard to age at onset, side effects, treatment plans, and options that were discussed with physicians. A prospective, randomized, double-blind assessment of treatment experiences (including psychotherapeutic interventions), correlated with physician perceptions and structured observation, would be a valuable next study, as would the assessment of outcomes and responses associated with different communication styles. The findings of a further research study that included a matched comparison group of patients who had achieved full remission would be of particular interest.

Since the diagnosis and treatment of major depressive disorder continue to emphasize the central role of the primary care physician, educational programs, patient advocacy, health care system changes and resources, and quality of care measures should focus on physician-patient communication, incomplete resolution, and process of care problems highlighted by these data. We have demonstrated in this large national telephone survey of predominantly married, female patients that even in a seemingly optimal clinical setting with educational and social support resources, many patients with chronic, recurrent depression are inappropriately accepting of treatment planning in which they are not engaged as full partners, treatment regimens that do not lead to full symptom remission, and an incomplete discussion of potential side effects. As is the case with other chronic illnesses, these deficiencies should not be accepted in the care of patients with chronic depression, even when patients appear to be satisfied with the care they receive.

|

|

|

|

|

Received June 19, 2003; revision received Feb. 24, 2004; accepted Feb. 29, 2004. From the Department of Family Medicine, University of Michigan Medical School; the Department of Psychiatry, University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia; MSE Communications, Cheshire, Conn.; and the Depression and Bipolar Support Alliance, Chicago. Address correspondence and reprint requests to Dr. Schwenk, Department of Family Medicine, L2003, Box 0239, Ann Arbor, MI 48109; [email protected] (e-mail). Supported by an unrestricted educational grant from GlaxoSmithKline, Inc., to the Depression and Bipolar Support Alliance, Chicago, under whose supervision and sponsorship the study was conducted. Additional statistical analysis was provided by Daniel Gorenflo, Ph.D., of the Department of Family Medicine, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor.

Figure 1. Disposition of Household Sample of 7,785 Primary Care Patients

Figure 2. Common Antidepressant Side Effects That 617 Patients Recalled Discussing With Their Physician in Advance of Starting Treatment

Figure 3. Medication Adherence Among 466 Patients Who Recalled Reporting Problems With Side Effects to Their Physicians

1. Herrman H, Patrick DL, Diehr P, Martin ML, Fleck M, Simon GE, Buesching DP: Longitudinal investigation of depression outcomes in primary care in six countries: the LIDO study: functional status, health service use and treatment of people with depressive symptoms. Psychol Med 2002; 32:889–902Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

2. Higgins ES: A review of unrecognized mental illness in primary care: prevalence, natural history, and efforts to change the course. Arch Fam Med 1994; 3:908–917Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

3. Kessler RC, McGonagle KA, Zhao S, Nelson CB, Hughes M, Eshleman S, Wittchen H-U, Kendler KS: Lifetime and 12-month prevalence of DSM-III-R psychiatric disorders in the United States: results from the National Comorbidity Survey. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1994; 51:8–19Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

4. Michaud CM, Murray CJ, Bloom BR: Burden of disease: implications for future research. JAMA 2001; 285:535–539Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

5. Institute of Medicine: Priority Areas for National Action: Transforming Health Care Quality. Edited by Adams K, Corrigan JM. Washington, DC, National Academies Press, 2003Google Scholar

6. Mulrow CD, Williams JW Jr, Trivedi M, Chiquette E, Aguilar C, Cornell JE: Treatment of Depression: Newer Pharmacotherapies: Evidence Report/Technology Assessment Number 7: AHCPR Publication 99-E104. Rockville, Md, Agency for Health Care Policy and Research, Feb 1999Google Scholar

7. Coyne JC, Klinkman MS, Gallo SM, Schwenk TL: Short-term outcomes of detected and undetected depressed primary care patients and depressed psychiatric patients. Gen Hosp Psychiatry 1997; 19:333–343Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

8. Schwenk TL, Klinkman MS, Coyne JC (The Michigan Depression Project): Depression in the family physician’s office: what the psychiatrist needs to know. J Clin Psychiatry 1998; 59(suppl 20):94–100Google Scholar

9. Schwenk TL, Coyne JC, Fechner-Bates S: Differences between detected and undetected patients in primary care and depressed psychiatric patients. Gen Hosp Psychiatry 1996; 18:407–415Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

10. Mental Health: A Report of the Surgeon General—Executive Summary. Rockville, Md, US Department of Health and Human Services, Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, Center for Mental Health Services, National Institutes of Health, National Institute of Mental Health, 1999Google Scholar

11. Depression Guideline Panel: Depression in Primary Care: Treatment of Major Depression, vols 1, 2: Clinical Practice Guideline Number 5: AHCPR Publication 93–0551. Rockville, Md, US Department of Health and Human Services, Public Health Service, Agency for Health Care Policy and Research, April 1993Google Scholar

12. Schulberg HC, Katon W, Simon GE, Rush AJ: Treating major depression in primary care practice: an update of the Agency for Health Care Policy and Research Practice Guidelines. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1998; 55:1121–1127Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

13. Snow V, Lascher S, Mottur-Pilson C (American College of Physicians-American Society of Internal Medicine): Pharmacologic treatment of acute major depression and dysthymia. Ann Intern Med 2000; 132:738–742Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

14. Ballenger JC, Davidson JR, Lecrubier Y, Nutt DJ, Goldberg D, Magruder KM, Schulberg HC, Tylee A, Wittchen H-U (International Consensus Group on Depression and Anxiety): Consensus statement on the primary care management of depression from the International Consensus Group on Depression and Anxiety. J Clin Psychiatry 1999; 60(suppl 7):54–61Google Scholar

15. Keller MB, Klerman GL, Lavori PW, Fawcett JA, Coryell W, Endicott J: Treatment received by depressed patients. JAMA 1982; 248:1848–1855Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

16. Hirschfeld RM, Keller MB, Panico S, Arons BS, Barlow D, Davidoff F, Endicott J, Froom J, Goldstein M, Gorman JM, Guthrie D, Marek RG, Maurer TA, Meyer R, Phillips K, Ross J, Schwenk TL, Sharfstein SS, Thase ME, Wyatt RJ: The National Depressive and Manic-Depressive Association consensus statement on the undertreatment of depression. JAMA 1997; 277:333–340Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

17. Schwenk TL: Diagnosis of late life depression: the view from primary care. Biol Psychiatry 2002; 52:157–163Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

18. Williams JW Jr, Mulrow CD, Kroenke K, Dhanda R, Badgett RG, Omori D, Lee S: Case-finding for depression in primary care: a randomized trial. Am J Med 1999; 106:36–43Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

19. Gerrity MS, Cole SA, Dietrich AJ, Barrett JE: Improving the recognition and management of depression: is there a role for physician education? J Fam Pract 1999; 48:949–957Medline, Google Scholar

20. Cabana MD, Rushton JL, Rush AJ: Implementing practice guidelines for depression: applying a new framework to an old problem. Gen Hosp Psychiatry 2002; 24:35–42Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

21. Katon W, von Korff M, Lin E, Bush T, Ormel J: Adequacy and duration of antidepressant treatment in primary care. Med Care 1992; 30:67–76Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

22. Simon GE, von Korff M: Recognition, management, and outcomes of depression in primary care. Arch Fam Med 1995; 4:99–105Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

23. Von Korff M, Katon W, Unutzer J, Wells K, Wagner EH: Improving depression care: barriers, solutions, and research needs. J Fam Pract 2001; 50:E1Google Scholar

24. Simon GE, Revicki D, Heiligenstein J, Grothaus L, Von Korff M, Katon WJ, Hylan TR: Recovery from depression, work productivity, and health care costs among primary care patients. Gen Hosp Psychiatry 2000; 22:153–162Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

25. Katon W, Von Korff M, Lin E, Bush T, Russo J, Lipscomb P, Wagner E: A randomized trial of psychiatric consultation with distressed high utilizers. Gen Hosp Psychiatry 1992; 14:86–98Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

26. Katon W, Von Korff M, Lin E, Lipscomb P, Russo J, Wagner E, Polk E: Distressed high utilizers of medical care: DSM-III-R diagnoses and treatment needs. Gen Hosp Psychiatry 1990; 12:355–362Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

27. Frank E, Perel JM, Mallinger AG, Thase ME, Kupfer DJ: Relationship of pharmacologic compliance to long-term prophylaxis in recurrent depression. Psychopharmacol Bull 1992; 28:231–235Medline, Google Scholar

28. Stewart M, Brown JB, Donner A, McWhinney IR, Oates J, Weston WW, Jordan J: The impact of patient-centered care on outcomes. J Fam Pract 2000; 49:796–804Medline, Google Scholar

29. Roter DL, Stewart M, Putnam SM, Lipkin M Jr, Stiles W, Inui TS: Communication patterns of primary care physicians. JAMA 1997; 277:350–356Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

30. Stewart MA: Effective physician-patient communication and health outcomes: a review. CMAJ 1995; 152:1423–1433Medline, Google Scholar

31. Lin EH, Von Korff M, Katon W, Bush T, Simon GE, Walker E, Robinson P: The role of the primary care physician in patients’ adherence to antidepressant therapy. Med Care 1995; 33:67–74Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

32. Bultman DC, Svarstad BL: Effects of physician communication style on client medication beliefs and adherence with antidepressant treatment. Patient Educ Couns 2000; 40:173–185Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

33. Ruscher SM, de Wit R, Mazmanian D: Psychiatric patients’ attitudes about medication and factors affecting noncompliance. Psychiatr Serv 1997; 48:82–85Link, Google Scholar

34. Bull SA, Hunkeler EM, Lee JY, Rowland CR, Williamson TE, Schwab JR, Hurt SW: Discontinuing or switching selective serotonin-reuptake inhibitors. Ann Pharmacother 2002; 36:578–584Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

35. Demyttenaere K, Enzlin P, Dewé W, Boulanger B, De Bie J, De Troyer W, Mesters P: Compliance with antidepressants in a primary care setting, 1: beyond lack of efficacy and adverse events. J Clin Psychiatry 2001; 62(suppl 22):30–33Google Scholar

36. Cabral DN, Napoles-Springer AM, Miike R, McMillan A, Sison JD, Wrensch MR, Perez-Stable EJ, Wiencke JK: Population- and community-based recruitment of African Americans and Latinos: the San Francisco Bay Area Lung Cancer Study. Am J Epidemiol 2003; 158:272–279Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

37. Kessler RC, McGonagle KA, Swartz M, Blazer DG, Nelson CB: Sex and depression in the National Comorbidity Survey, I: lifetime prevalence, chronicity and recurrence. J Affect Disord 1993; 29:85–96Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar