Predictors of Antidepressant Prescription and Early Use Among Depressed Outpatients

Abstract

OBJECTIVE: The rates of antidepressant recommendation and use were determined in outpatients with major depression receiving services in mental health clinics. Site of service and the patients’ sociodemographic and clinical characteristics were investigated as possible predictors. METHOD: Patients admitted to six outpatient clinics were recruited through a two-stage sampling procedure. Patients with major depressive disorder (N=124) according to the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV—Patient Edition were assessed at admission and 3 months later. RESULTS: Drug therapy was recommended for most patients (71%), and minimal use (at least 1 week) was recorded for 59% of the subjects. White patients were nearly three times as likely to receive a recommendation for antidepressants. Antidepressant recommendation was also associated with severity of depressed mood, recent medication use, and clinic type. Recent antidepressant use was the only variable that predicted whether the patient actually took the recommended medication. CONCLUSIONS: Many patients with depression seeking treatment at community mental health clinics do not receive antidepressant drug therapy. The offer of medication is predicted by patient ethnicity, clinic type, and symptom severity. Minority patients are less likely to be offered antidepressant treatment.

Depression is a highly prevalent psychiatric disorder (1) with a chronic and relapsing course (2). If left untreated, depression may lead to significant personal and social costs because of the increased risk of suicide (3), social impairment (4), and increased use of health services (5, 6). Despite available pharmacologic treatments with proven efficacy, many depressed outpatients receive either no pharmacologic intervention or a medication regime that is suboptimal in dose and/or duration (7–9). Only 34% of the individuals with major depression treated in community facilities before being recruited into the NIMH Collaborative Depression Study had received antidepressant treatment for 4 consecutive weeks. Even after entry into the study, only 19% of the patients with depression received intensive antidepressant treatment, defined as at least 200 mg/day of imipramine or its equivalent for 4 consecutive weeks, and 29% did not receive antidepressants at all (10).

To date, few studies have investigated predictors of use or adequacy of antidepressant drug treatment. Those that have were conducted with predominantly middle-class individuals seeking treatment at university-based tertiary care centers, potentially obscuring the contribution of ethnic and sociodemographic variables to the prescription and use of antidepressants (11). Among the outpatients treated in the community before joining the NIMH collaborative study, severity and duration of depressive symptoms, psychic anxiety, and prior hospitalizations were associated with more intensive medication treatment, although the majority received suboptimal doses (8). During the follow-up phase of the NIMH collaborative study, high family income, impaired concentration, and psychomotor agitation were predictors of high-intensity treatment. However, these factors accounted for only 18% of the variance. Limited understanding of the determinants of pharmacotherapy among patients in the mental health sector has led to the call for further research on patient- and provider-related factors that contribute to the “serious undertreatment” of depression (11).

Investigations of depression among minority groups have demonstrated both diminished access to and use of mental health services (12–14) and lower-quality care for individuals seeking services (15). It is unclear, however, whether ethnicity influences differences in the prescription of antidepressants as well. In this study we investigated factors affecting medication prescription and initiation of medication use in a socioeconomically and racially diverse group of outpatients in order to elucidate potential effects of ethnicity and socioeconomic status, as well as treatment setting. The patients were drawn from diverse clinics in a county with rural, suburban, and urban communities. The hypotheses tested were that both greater symptom severity and treatment seeking at a university-based clinic staffed with a high proportion of psychiatrists would be associated with a greater likelihood of antidepressant drug treatment. We also hypothesized that patients from lower socioeconomic and minority groups would be less likely to receive pharmacotherapy regardless of the setting in which they sought treatment. Because a recommendation for antidepressant drug therapy may not coincide with actual use, we investigated predictors of both medication recommendation and initiation of medication use.

METHOD

Design

The subjects were consecutive patients newly admitted to selected mental health outpatient clinics in Westchester County, N.Y. The 1996 U.S. census estimates that the county has 893,412 residents, of whom 73% are white and 26% are minority. The residents live in a broad range of urban, suburban, and rural communities, ranging from small rural villages to Yonkers, which is the third largest city in New York state according to the 1990 census estimate reported by the Westchester County Census Bureau. After consultation with the Westchester County Office of Mental Health, clinics were selected as sample sites on the basis of their location, to include rural and urban populations, and the patient population served, to include both minority and nonminority communities. Consecutively admitted patients were screened on site in six mental health facilities: one independently funded clinic, three county clinics, a psychiatric clinic in a general community hospital, and a university-based clinic. The subjects were between 18 and 64 years of age. Elderly persons (aged 65 years or older) were excluded from these analyses as the majority (79%) of elderly patients screened sought service at the university-based clinic program specializing in studies of antidepressant efficacy for geriatric patients.

The study used a two-stage sampling procedure to identify newly admitted patients with unipolar major depressive disorder. After the study was described to new patients, written informed consent was obtained for the screening. The phase I assessment consisted of administration of the Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale (CES-D Scale) (16), to determine the severity of depressive symptoms, and the Mini International Neuropsychiatric Interview (17), to assess the presence of the DSM-IV criteria for major depressive disorder. A CES-D Scale cutoff score of 16 or higher was used to identify cases of probable depression because of the reported high sensitivity (96%) of this score in psychiatric outpatients (18). The Mini International Neuropsychiatric Interview has high sensitivity (96%) and specificity (88%) in identifying major depressive disorder in psychiatric samples (17). A positive finding with either instrument was the entry criterion for the phase II assessment, which included administration of the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV—Patient Edition (SCID-P) (19) to establish the diagnosis of major depressive disorder. Patients who screened positive for depression were contacted again, and written consent was obtained for participation in the phase II assessment and follow-up. The exclusion criteria included cognitive impairment as defined by a score of less than 24 on the Mini-Mental State (20), alcohol or substance abuse within the last month, and the presence of another axis I disorder.

Of the 815 newly admitted patients aged 18–64 years, 772 (95%) consented to the phase I assessment. Of those screened, 565 (73%) were positive for depressive symptoms. Of the 565 patients eligible for phase II interviews, 174 refused further follow-up, 55 could not be contacted again, and 336 (59%) consented to having the more extensive phase II diagnostic assessment. The phase II assessments were conducted by two research assistants and a clinical psychologist who were trained in the administration of the SCID-P and the Global Assessment of Functioning (21) with satisfactory interrater reliability (intraclass correlation coefficient=0.81). Over one-half (54%, 183 of 336) of the newly admitted patients who screened positive for depression met the criteria for major depressive disorder. One-quarter (23%, N=77) of those who screened positive for depression had bipolar or schizoaffective disorder, and one-quarter (23%, N=76) did not meet the criteria for an affective disorder. Only patients with the primary diagnosis of major depressive disorder or major depressive disorder with concurrent dysthymia were included in the follow-up group. Of the patients meeting these diagnostic criteria (N=183), 35 were excluded because of cognitive impairment or recent substance abuse, leaving 148 patients available for follow-up.

The subjects who met the inclusion criteria were evaluated with the structured interview guide for the 17-item Hamilton Depression Rating Scale (22, 23) to assess symptom severity. Information on duration of illness, suicidality, and prior episodes was gathered during administration of the SCID-P. The Global Assessment of Functioning Scale (21) was used to assess overall functioning. Concurrent medical illness was recorded by using the Chronic Disease Score (24), which assigns points for classes of medications prescribed for significant medical illnesses. While the presence of concurrent axis II personality disorders was not assessed, the 47-item version of the Inventory of Interpersonal Problems was administered and used as a screen for personality pathology (25). A cutoff score of 1.1 on the first three subscales of the Inventory of Interpersonal Problems was chosen to screen for interpersonal difficulties; this cutoff score had a reported sensitivity of 71% and specificity of 67% in outpatients with mood disorders (25).

Follow-up interviews were conducted 3 months after clinic admission. The patients were interviewed to determine the treatment recommended, services used, and current symptoms as indicated by the Mini International Neuropsychiatric Interview and the CES-D Scale. Interviews were completed for 84% of the 148 major depression patients (N=124). There were no differences in age, sex, ethnicity/race, depression severity, or overall functioning of the patients who were and were not able to be interviewed 3 months after admission. However, follow-up assessments were completed by a larger proportion of patients recruited from the university-based clinic (92%, 56 of 61) than patients recruited from the community outpatient clinics (78%, 50 of 64) (χ2=5.61, df=1, p=0.02).

Antidepressant Treatment

Information on whether antidepressant treatment was recommended and on the dose and duration of treatment was collected from patient report and chart review. The average rate of concordance between the patient reports and chart records for whether medication was prescribed, across the university-based and county-funded mental health clinics, was 83%. When the patient report and chart notes were discrepant, the chart review data were used in the analyses.

Antidepressant use was recorded for both the 3 months before clinic intake and the 3-month follow-up period by using a modified version of the composite antidepressant treatment score described by Alexopoulos et al. (26). An objective of this study was to identify predictors of medication recommendation and factors that contribute to initiation of medication treatment. To this end, antidepressant use was defined as 1 week of medication use during the 3-month follow-up period. Recent use before admission was defined similarly, i.e., at least 1 week of use during the 3 months before the index admission. Adequacy of medication dose and its relation to outcome were not investigated.

Characteristics of Sample

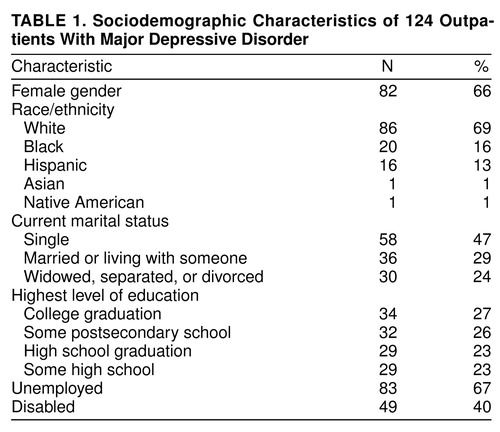

All of the patients were between the ages of 18 and 64 years; the mean age was 38.93 years (SD=12.70). Other sociodemographic characteristics of the sample are summarized in table 1. Of the 124 patients, 31% belonged to ethnic minority groups, predominantly African American and Hispanic. The majority of patients reported being unemployed, and many reported being disabled.

Site of service, comorbid conditions, and history of hospitalization are presented in table 2. The patients’ mean score on the Global Assessment of Functioning Scale was 45.9 (SD=8.8), and their mean score on the Hamilton depression scale was 19.5 (SD=4.8). All of the followed patients met the DSM-IV criteria for major depressive disorder. More than one-quarter met the criteria for prior alcohol abuse but reported no use in the past month. One-fifth reported one or more previous psychiatric hospitalizations. Comparisons of the patients seen in the two types of clinics (mental health outpatient clinics versus the university-based clinic) revealed no differences in the baseline severity of depression, history of alcohol or substance abuse, or overall functioning as measured by the Global Assessment of Functioning Scale.

Statistical Methods

We conducted chi-square analyses of the dichotomous demographic and clinical variables to establish 1) the likelihood of receiving a recommendation for drug therapy and 2) the likelihood of initiating medication use when recommended. Differences between groups (e.g., medication recommended or not) in continuous measures were analyzed by using t tests. Variables found to be significant in bivariate comparisons at the 0.10 level or better were entered into a series of logistic regression analyses to build the best predictive model of group membership. To identify specific depressive symptoms associated with medication referral, we used t test comparisons of mean group scores on specific Hamilton depression scale items. To account for multiple comparisons in the analyses of Hamilton scale items, a Bonferroni correction was calculated and a significance level of p<0.002 was used (27). Two-tailed significance was used. Statistical analyses were conducted by means of SAS (28).

RESULTS

Recommendation of Antidepressant Medication

During the 3 months after admission, medication was recommended for the majority (71%, 88 of 124) of depressed persons seeking help from the mental health outpatient clinics. For most of these patients antidepressants were recommended during the initial evaluation, while for a few (N=6) medication was recommended later in treatment. Comparisons by type of clinic demonstrated that recommendations for medication were received by a larger proportion of patients seeking help at the university-based clinic (87%, N=53) than patients seen at the other clinics (57%, N=36) (χ2=12.10, df=1, p<0.001). As expected, a higher percentage of the overall clinical hours was provided by psychiatrists or psychiatric residents in the university-based clinic (67%) than in the other mental health facilities (7%–42%). In addition, the community-based clinics used only nonmedical staff to conduct the intake evaluations, whereas the evaluations at the university-based clinic were conducted by all disciplines.

Predictors of Antidepressant Recommendation

Analyses of bivariate associations between patient sociodemographic characteristics and medication recommendation revealed that only ethnicity/race was associated with antidepressant recommendation: a larger proportion of nonminority patients (84%, N=72) than minority patients (45%, N=17) received recommendations for antidepressants (χ2=17.89, df=1, p<0.001). The number of minority patients (N=38) was too small for stratified analyses. Post hoc comparisons of the black, Hispanic, and white patients indicated that a larger proportion of white patients (84%, N=72) received a recommendation for antidepressant drugs than either the black patients (30%, N=6) (χ2=18.16, df=1, p<0.001) or Hispanic patients (56%, N=9) (χ2=4.67, df=1, p=0.03). There was no difference in recommendations for medication between the two minority groups (χ2=1.56, df=1, p=0.21). Recommendation for antidepressant medication was not associated with differences in gender, age, education, employment status, disability status, income, marital status, living arrangements, or method of payment (Medicaid, fee for service, managed care, or other insurance).

The two types of clinics, university based and community, differed in the association between ethnic/racial status and recommendation for antidepressant drugs. At the community sites, medication was significantly less likely to be recommended to minority patients; 74% of the nonminority patients (25 of 34) and only 38% of the minority patients (11 of 29) received recommendations for medication (χ2=6.71, df=1, p=0.01). At the university-based clinic, the difference was not significant: medication was recommended for 90% of the nonminority patients (47 of 52) and 67% of the minority patients (six of nine) (χ2=1.99, df=1, p=0.16). According to the data elicited by the SCID-P, there were no differences between minority and nonminority patients in the presence of specific depressive phenomena (such as melancholic or atypical symptoms), suicidality, age at onset, or duration of current episode. Exploratory comparisons of the minority and nonminority patients’ symptoms as shown by the Hamilton depression scale indicated that the minority patients reported greater weight loss (t=2.15, df=123, p=0.03) and the white patients reported greater disruption of work and/or activities. According to the SCID-P, there were no differences in clinical presentation (e.g., specific major depression criteria endorsed, presence of melancholic or atypical symptoms, suicidal ideation, age at onset, or duration of current episode). There were no other sociodemographic variables (e.g., gender, age, employment, self-reported disability, or marital status) that differed between the patients who did and did not receive recommendations for antidepressant medication.

The patients who received a recommendation for antidepressant treatment had higher overall scores on the Hamilton depression scale (mean=9.7, SD=5.0) than the patients who did not receive a recommendation for medication (mean=18.0, SD=3.6) (t=2.00, df=123, p=0.02). Medication recommendation was more likely among patients with a prior psychiatric hospitalization (88%, N=22) than among individuals who had never been hospitalized (67%, N=67) (χ2=3.13, df=1, p=0.08). Medication recommendation was not associated with differences in the subtype of depression (atypical, melancholic), suicidal ideation, duration of current illness, prior episodes of depression, or presence of a medical illness. Using the cutoff score of 1.1 on the Inventory of Interpersonal Problems, the screen for personality disorders, we found that patients with and without significant personality pathology were equally likely to receive recommendations for medication. Recent antidepressant treatment was a significant predictor of medication recommendation; 98% of the patients (39 of 40) with a recent history of prior antidepressant use (at least 1 week of use during the 3 months before intake) received a recommendation for antidepressant medication, compared to 60% of the patients without recent antidepressant use (50 of 84) (χ2=17.46, df=1, p<0.001).

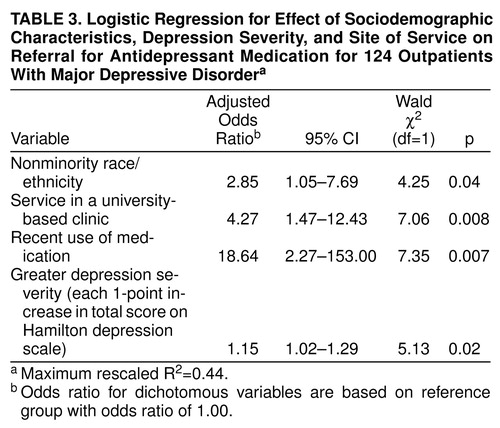

Logistic regression was used to determine the independent effects of historical, sociodemographic, clinical, and site factors significant in bivariate comparisons at the p<0.10 level (table 3). White patients were almost three times as likely to receive a recommendation for antidepressants than minority patients, even after we controlled for severity of depression, site, and recent use of medication. Site of service remained a significant predictor of medication recommendation, such that patients with major depressive disorder who sought help at the university-based clinic were more than four times as likely to receive a medication recommendation than patients seen at other outpatient mental health clinics. To explore the differential treatment of minority patients by site, an interaction term (clinic type by ethnicity) was entered into the model. The term did not significantly contribute to the model. With depression severity controlled, the patients with recent antidepressant use were 18 times as likely to receive a medication recommendation than individuals without recent antidepressant use. When the Hamilton score was used as a continuous variable, overall depression severity continued to predict the likelihood of medication recommendation, such that each additional point on the scale was associated with a 1.15 odds of having medication recommended. Prior hospitalization did not contribute to the model. The four variables in the model accounted for 44% of the total variance.

The model created by the logistic regression analyses correctly predicted group membership (medication recommended or not recommended) for 82% of the patients, 92% of those who actually received medication recommendations (81 of 88) and 60% of those who did not receive medication recommendations (21 of 36).

To identify the depressive symptom profile of individuals who received a medication recommendation, we compared scores on the individual items of the Hamilton depression scale for these patients with scores for the patients who were not referred for medication. The patients referred for medication had significantly higher scores on the item for depressed mood than did the patients not referred for antidepressant treatment (t=3.84, df=123, p<0.001). This was the only symptom significant at the p=0.002 level or better; none of the other items approached significance. To examine whether depressed mood contributed more to the overall model than did the total Hamilton depression scale score, a separate logistic regression was conducted. Depressed mood was a more significant clinical predictor of medication recommendation than overall severity (odds ratio=3.80, χ2=6.78, df=1, p=0.009).

Predictors of Antidepressant Use

In the total sample of 124 patients with major depression who were followed for 3 months, 59% of the patients (N=73) took a prescribed antidepressant for at least 1 week during the 3-month follow-up period. Of the 88 patients for whom antidepressants were recommended, 83% (N=73) reported that they took an antidepressant medication for at least 1 week. Of the patients who took the recommended antidepressant, 86% (63 of 73) continued to take the medication for 4 weeks or longer. Only recent use of antidepressants was a significant predictor of actual medication use. All of the patients who reported antidepressant use before admission and received a recommendation for antidepressant medication took the recommended antidepressant, as compared to 70% of the individuals with no prior use of medication. The liberal definition of prior use contributes to the high use rate among individuals who received an antidepressant recommendation and may have limited our ability to identify other factors that contribute to use of the recommended antidepressant medication. There were no other clinical, sociodemographic (age, sex, payment type), or site characteristics associated with medication use.

DISCUSSION

The principal finding of the study is the negative impact of minority group membership on medication recommendation, despite the absence of differences in depression severity or functional status. This finding is of particular concern. Our data suggest that little has changed since Hollingshead and Redlich (29) reported that social class and site of service influenced treatment recommendations in their 1958 study of social class and mental illness. Our data add to the current literature indicating that racial/ethnic factors influence treatment given by providers (e.g., diagnosis, medication prescription, hospitalization) and, therefore, affect quality of care (13, 30, 31). Lower rates of antidepressant recommendation for minority patients may reflect a lack of recognition of major depression by either clinicians or patients. Clinicians may misattribute affective distress in these patients to real-world stress-inducing factors that they perceive to be unresponsive to antidepressant treatment. Alternatively, minority patients may overtly or covertly communicate reluctance to take antidepressants due to stigma or other attitudinal barriers. Cooper-Patrick et al. (32) found that black patients were more likely to refuse medication because of the fear of addiction. Further research is needed to identify factors contributing to racial differences in the recommendation of antidepressant therapy and to determine the effect of these factors and the bias reported on clinical outcome.

The increased likelihood of a recommendation of antidepressant therapy for patients with recent antidepressant use suggests that once drug therapy is initiated it may be effectively used for future episodes of depression, if necessary. The association between recent medication treatment and actual use may reflect either clinician awareness of disorder severity or patient willingness to receive pharmacotherapy.

Site of service contributed significantly to referral for medication such that patients attending the university-based clinic were more likely to receive a recommendation for medication. The greater number of psychiatrists, their participation in the intake process, and/or differences in treatment philosophy could have contributed to the identified differences. Our grouping of nonacademic clinics together on the basis of staffing patterns could also mask more subtle factors, including treatment philosophy, that influence treatment recommendations. Nevertheless, the data demonstrating that, given the same disorder, where patients go for help determines the treatment they receive has important public health significance.

To identify patient demographic, clinical, and prior treatment predictors of antidepressant treatment in the community, we focused on reported antidepressant recommendation and a liberal criterion for use. Since we are most interested in understanding the treatment process and in this study focused on the initiation of medication, the data presented do not address the adequacy of the pharmacotherapy or its outcome. Analysis of intensity of dose or duration of pharmacotherapy and its relationship to clinical or functional outcomes is beyond the scope of our study. Similarly, in this study we did not address recommendations for psychotherapy, whether this was provided to patients, and the impact of psychosocial treatment on outcome. The data generated shed light on the process of selection of a specific treatment modality as a first step toward improving quality of care for major depression.

Finally, we restricted our sample to patients aged 18–64 years who sought treatment at outpatient mental health clinics. Epidemiological data (1, 33) demonstrate that approximately 50% of patients with major depression receive treatment in primary care facilities. Many patients seek help from private clinicians, whose practices are difficult to quantify beyond survey methods that provide limited insight into the process of treatment selection. These analyses were limited to individuals aged 18–64 since our screening procedures identified too few elderly individuals (with or without major depression) seeking mental health service at community outpatient clinics to conduct meaningful analyses. Epidemiologic Catchment Area (12, 34) and survey (35)) data indicate that elderly individuals in need of help are less likely to seek treatment from mental health practitioners. We cannot ascertain the extent to which the depressed patients in our study are representative of Westchester County or the general population. However, a unique feature of this study is the inclusion of a broad range of patients, including patients seeking care at public mental health clinics, who are not included in controlled treatment studies. These patients may represent a group of treatment-seeking individuals who are more representative of an urban patient population.

In sum, our data suggest that major depression occurs in more than one-half of patients newly admitted to outpatient mental health clinics. Consistent with findings published more than a decade ago (8, 10) and despite data supporting the efficacy of antidepressants, only slightly more than one-half of the patients with major depressive disorder in this study received antidepressant treatment. Our data suggest that the low rate of use reflects both the lack of a medication recommendation for some patients and, if recommended, the medication not being taken. Since the majority of the patients who initiated treatment continued to take the medication for at least 4 weeks, it is important to identify barriers to medication recommendation. Our data suggest that the treatment recommendations are influenced by sociodemographic characteristics of the patient, site of service, and clinical status. While most patients did receive a recommendation for antidepressant medication, significant variability was identified in both clinician practice and specific patient-related factors influencing the recommendation and use of medication. Our data underscore the importance of understanding the process of treatment selection and implementation as the first step to improving the quality of care for all individuals who seek help for depression in mental health settings.

Presented at the NIMH Conference on Improving the Condition of People with Mental Illness: The Role of Services Research, Washington, D.C., Sept. 4–5, 1997. Received March 20, 1998; revision received Sept. 28, 1998; accepted Nov. 16, 1998. From the Department of Psychiatry, The New York Presbyterian Hospital and Joan and Sanford I. Weill Medical College of Cornell University. Address reprint requests to Dr. Sirey, Department of Psychiatry, The New York Presbyterian Hospital, Joan and Sanford I. Weill Medical College of Cornell University, 21 Bloomingdale Rd., White Plains, NY 10605; jsirey%[email protected] (e-mail). Supported by NIMH grant MH-53816 to Dr. Meyers. The authors thank Steven J. Friedman, M.S., for his support, Mark S. Olfson, M.D., for his suggestions, and S. Bankier, I. O’Brien, T. DiDomenico, M. Hamilton, C. Mackay, B. Myers, and L. Piccone for their help.

|

|

|

1. Kessler RC, McGonagle KA, Zhao S, Nelson CB, Hughes M, Eshleman S, Wittchen H-U, Kendler KS: Lifetime and 12-month prevalence of DSM-III-R psychiatric disorders in the United States: results from the National Comorbidity Survey. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1994; 51:8–19Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

2. Keller MB, Lavori PW, Mueller TI, Endicott J, Coryell W, Hirschfeld RM, Shea T: Time to recovery, chronicity, and levels of psychopathology in major depression: a 5-year prospective follow-up of 431 subjects. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1992; 49:809–816Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

3. American Psychiatric Association: Practice Guideline for Major Depressive Disorder in Adults. Am J Psychiatry 1993; 150(April suppl)Google Scholar

4. Coryell W, Endicott J, Winokur G, Akiskal H, Solomon D, Leon A, Mueller T, Shea T: Characteristics and significance of untreated major depressive disorder. Am J Psychiatry 1995; 152:1124–1129Google Scholar

5. Regier DA, Narrow WE, Rae DS, Manderscheid RW, Locke BZ, Goodwin FK: The de facto US mental and addictive disorders service system: Epidemiologic Catchment Area prospective 1-year prevalence rates of disorders and services. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1993; 50:85–94Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

6. Katon W, Von Korff M, Lin E, Bush T, Ormel J: Adequacy and duration of antidepressant treatment in primary care. Med Care 1992; 30:67–76Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

7. Weissman MM, Klerman GL: The chronic depressive in the community: unrecognized and poorly treated. Compr Psychiatry 1977; 13:523–532Crossref, Google Scholar

8. Keller MB, Klerman GL, Lavori PW, Fawcett JA, Coryell W, Endicott J: Treatment received by depressed patients. JAMA 1982; 248:1848–1855Google Scholar

9. Keller MB: Underrecognition and undertreatment by psychiatrists and other health care professionals (letter). Arch Intern Med 1990; 150:946–948Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

10. Keller MB, Lavori PW, Klerman GL, Andreasen NC, Endicott J, Coryell W, Fawcett J, Rice JP, Hirschfeld RMA: Low levels and lack of predictors of somatotherapy and psychotherapy received by depressed patients. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1986; 43:458–466Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

11. Hirschfeld RMA, Martin BK, Panico S, Arons BS, Barlow D, Davidoff F, Endicott J, Froom J, Goldstein M, Gorman JM, Marek RG, Maurer TA, Meyer R, Phillips K, Ross J, Schwenk TL, Sharfstein SS, Thase ME, Wyatt RJ: The National Depressive and Manic-Depressive Association consensus statement on the undertreatment of depression. JAMA 1997; 277:333–340Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

12. Leaf PJ, Bruce ML, Tischler GL, Freeman DH, Weissman MM, Myers JK: Factors affecting the utilization of specialty and general medical mental health services. Med Care 1988; 26:9–26Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

13. Wells KB, Golding JM, Hough RL, Burnam MA, Karno M: Acculturation and the probability of use of health services by Mexican Americans. Health Serv Res 1989; 24:237–257Medline, Google Scholar

14. Cooper-Patrick L, Crum RM, Ford DE: Characteristics of patients with major depression who received care in general medical and specialty mental health settings. Med Care 1994; 32:15–24Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

15. Abe-Kim JS, Takeuchi DT: Cultural competence and quality of care: issues for mental health service delivery in managed care. Clin Psychol Sci Pract 1996; 3:273–295Crossref, Google Scholar

16. Radloff LS: The CES-D Scale: a self-report depression scale for research in the general population. J Applied Psychol Measurement 1977; 1:385–401Crossref, Google Scholar

17. Sheehan DV, Lecrubier Y, Sheehan KH, Janavs J, Weiller E, Keskiner A, Schinka J, Knapp E, Sheehan MF, Dunbar GC: The validity of the Mini International Neuropsychiatric Interview (MINI) according to the SCID-P and its reliability. Eur Psychiatry 1997; 12:232–241Crossref, Google Scholar

18. Schulberg HC, Saul M, McClelland M, Ganguli M, Christy W, Frank R: Assessing depression in primary medical and psychiatric practices. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1985; 42:1164–1170Google Scholar

19. First MB, Spitzer RL, Williams JBW, Gibbon M: Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV—Patient Edition (SCID-P). Washington, DC, American Psychiatric Press, 1995Google Scholar

20. Folstein MF, Folstein SE, McHugh PR: “Mini-Mental State”: a practical method for grading the cognitive state of patients for the clinician. J Psychiatr Res 1975; 12:189–198Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

21. Endicott J, Spitzer RL, Fleiss JL, Cohen J: The Global Assessment Scale: a procedure for measuring overall severity of psychiatric disturbance. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1976; 33:766–771Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

22. Hamilton M: A rating scale for depression. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 1960; 23:56–62Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

23. Williams JB: A structured interview guide for the Hamilton Depression Rating Scale. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1988; 45:742–747Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

24. Von Korff M, Wagner EH, Saunders K: A chronic disease score from automated pharmacy data. J Clin Epidemiol 1992; 45:197–203Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

25. Pilkonis PA, Yookyung K, Proietti JM, Barkham M: Scales for personality disorders developed from the Inventory of Interpersonal Problems. J Personal Disord 1996; 10:355–369Crossref, Google Scholar

26. Alexopoulos GS, Meyers BS, Young RC, Kakum T, Feder M, Einhorn A, Rosendahl E: Recovery in geriatric depression. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1996; 53:305–312Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

27. Feller W: An Introduction to Probability Theory and Its Application. New York, John Wiley & Sons, 1968, pp 110, 142Google Scholar

28. DiIorio FC: SAS Applications Programming: A Gentle Introduction. Belmont, Calif, Duxbury Press, 1991Google Scholar

29. Hollingshead AB, Redlich FC: Social Class and Mental Illness: A Community Study. New York, John Wiley & Sons, 1958Google Scholar

30. Brown DR, Ahmed F, Gary LE, Milburn NG: Major depression in a community sample of African Americans. Am J Psychiatry 1995; 152:373–378Link, Google Scholar

31. Mukherjee S, Shukla S, Woodle J, Rosen AM, Olarte S: Misdiagnosis of schizophrenia in bipolar patients: a multiethnic comparison. Am J Psychiatry 1983; 140:1571–1574Google Scholar

32. Cooper-Patrick L, Powe NR, Jenckes MW, Gonzalez JJ, Levine DM, Ford DE: Identification of patient attitudes and preferences regarding treatment of depression. J Gen Intern Med 1997; 12:431–438Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

33. Narrow WE, Regier DA, Rae DS, Manderscheid RW, Locke BZ: Use of services by persons with mental and addictive disorders: findings from the National Institute of Mental Health Epidemiologic Catchment Area Program. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1993; 50:95–107Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

34. Shapiro S, Skinner EA, Kessler LG, Von Korff M, German PS, Tischler GL, Leaf PJ, Benham L, Cottler L, Regier DA: Utilization of health and mental health services: three Epidemiologic Catchment Area sites. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1984; 41:971–978Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

35. Waxman HM, Carner EA: Physicians’ recognition, diagnosis and treatment of mental disorders in elderly medical patients. Gerontologist 1984; 24:593–597Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar