Trends in Office-Based Psychiatric Practice

Abstract

OBJECTIVE: The authors examine trends in the composition and duration of visits to psychiatrists in office-based psychiatric practice. METHOD: An analysis was performed of physician-reported data from the 1985 and 1995 National Ambulatory Medical Care Surveys focusing on visits to physicians specializing in psychiatry. Secular changes in visit characteristics were assessed, and mean visit durations were determined for selected sociodemographic and clinical groups. RESULTS: In the decade between 1985 and 1995, visits in office-based psychiatry became shorter, less often included psychotherapy, and more often included a medication prescription. The proportion of visits that were 10 minutes or less in length increased. A shortening in visit duration was most evident for younger patients, privately insured patients, and patients who were not prescribed a psychotropic medication. In the 1995 survey, 6.8% of the psychiatric visits included patient contact with another health care professional. CONCLUSIONS: Changing financial arrangements and new pharmacologic treatments may have contributed to these changes in practice style. (Am J Psychiatry 1999; 156:451–457)

The growth of managed care is widely believed to have changed the manner in which mental health services are provided (1). Administrative and fiscal mechanisms, such as reduced or discounted physician fees, utilization management protocols, and case management, are thought to have altered the clinical functions of psychiatrists. Some psychiatrists express concern that supply-side financial pressures and administrative policies have narrowed their clinical roles and threatened or eroded the quality of care. In particular, there is concern that psychotherapy has been passed over to less highly paid health care professionals and that psychiatrists are increasingly restricted to managing pharmacologic treatments during brief visits (2, 3). Financial pressures have been blamed for leading some psychiatrists to adopt a style of practice characterized by high patient volume, rapid patient turnover, short medication management visits, and little psychotherapy (4). For the most part, however, these characterizations of psychiatric practice have been developed from anecdotes and general impressions rather than systematic analysis of nationally representative data.

In the present article, we draw on a nationally representative sample of visits to office-based practices to examine recent changes in the delivery of services. We examine changes in the mix of patients treated and the treatments provided. We focus in greatest detail on the period of time psychiatrists report spending with individual patients.

The practice of psychiatry is inherently time-intensive. The disorders that psychiatrists treat generally become evident only through a time-consuming process of questioning, listening, and interacting with patients. Psychotherapy, which has historically been the foundation of psychiatric practice, is almost by definition a time-intensive process. Previous research suggests that a time-intensive style of treatment is one of the basic characteristics that distinguishes the mental health care provided by psychiatrists from that provided by other medical specialists (5, 6).

The amount of time a psychiatrist actually spends with a patient is highly variable. Demographic, diagnostic, financial, and practice variables are all thought to influence the duration of psychiatric visits. Previous research suggests that shorter visits, for example, tend to be provided to older patients, publicly financed patients, and patients with psychotic disorders (7).

In the present article, we compare the clinical characteristics and visit durations of a sample of office-based psychiatric visits from 1985 and 1995. Before conducting these analyses, we hypothesized that there has been an overall decline in the duration of psychiatric visits, a parallel decline in the use of psychotherapy, and an increase in the prescription of psychotropic medications. We further hypothesized that this change would have its greatest effect on patients who have historically had comparatively long patient visits, such as those who have nonpsychotic disorders and those who are treated without psychotropic medications.

METHOD

Source of Data

The source of data for this article is the National Ambulatory Medical Care Survey (8). The National Ambulatory Medical Care Survey, which is conducted annually by the National Center for Health Statistics, samples a nationally representative group of visits to physicians in office-based practice. Attending physicians or their office staff complete a one-page data form for each visit during a specified 1-week period. The present article is based on results from the 1985 and 1995 National Ambulatory Medical Care Surveys.

The two surveys used similar instruments to collect data on office-based visits. They used identical items to collect information on patient age, sex, race, visit status, diagnosis, medication therapy, psychotherapy, and visit duration. The item concerning expected source of payment was modified, as described below, and a new item concerning treatment by other professionals was added to the 1995 survey. There was no change in the sampling plan or survey methodology.

Survey Design

The surveys were conducted by means of a three-stage sampling design. First, a probability sample of 112 primary sampling units (a county, a group of adjacent counties, or a standard metropolitan statistical area) was drawn, then a probability sample was drawn of practicing physicians within these primary sampling units, and finally, a systematic random sample was drawn of the visits to these physicians. Physicians expecting more than 10 visits per day recorded visits on the basis of a predetermined sampling interval. Some patient duplication may occur with this survey design.

Sample of Psychiatrists

The present analysis is confined to visits to psychiatrists in office-based practices. Psychiatrists include physicians specializing in general psychiatry or a psychiatric subspecialty such as child psychiatry or psychoanalysis. The surveys do not include psychiatrists practicing in federal facilities, hospital-based clinics, emergency departments, or other hospital settings. The 1985 National Ambulatory Medical Care Survey questioned 178 psychiatrists, and the 1995 National Ambulatory Medical Care Survey questioned 186 psychiatrists. The response rate was 74% in 1985 and 73% in 1995.

Variable Definitions

Visit duration is defined as the time that the psychiatrist spends in face-to-face contact with the patient. It specifically excludes the time that the patient spends waiting to see the psychiatrist or receiving care from someone other than the psychiatrist. If the patient did not see the psychiatrist at all (e.g., clinical decisions made on the basis of reports provided by other clinicians), the visit duration is defined as zero.

In the 1985 survey, a single item was used to collect data on the expected source of payment for the visit. It included eight response categories: self-pay, Medicare, Medicaid, Blue Cross/Blue Shield, other commercial insurance, HMO or prepaid plans, no charge, and a residual “other” category. In the 1995 survey, separate items were used to collect data on the type of payment (preferred provider option, fee-for-service insurance, HMO or prepaid, self-pay, no charge, and “other”) and expected payment source. The expected payment source response items of the 1985 and 1995 surveys were identical except that self-pay was considered a type of payment in the 1995 survey.

Six mutually exclusive visit payment categories were created: 1) self-pay, which includes self-pay as an expected source of payment or type of payment and excludes visits covered by insurance; 2) HMO or other prepayment, which includes visits through HMOs or similar organizations; 3) fee-for-service private insurance, which includes visits through Blue Cross/Blue Shield or other commercial insurance and excludes visits through HMOs or other prepayment source; 4) fee-for-service public insurance, which includes visits through Medicare or Medicaid and excludes all visits through private insurance or HMO/prepayment; 5) other, which includes no charge; and 6) a residual group of other expected types and sources of payment.

Some of the analyses involve aggregating visits into broad categories by first-listed or primary diagnosis. These groups, which are based on ICD-9-CM criteria, include depressive disorders (296.2, 296.3, 300.4, 311), anxiety disorders (300.0–300.3), adjustment disorders (308, 309 [except 309.8]), bipolar disorder (296.0, 296.1, 296.4–296.9), schizophrenia and related disorders (295, 297–299, 780.1), personality disorder (301), disorders of childhood and mental retardation (312–319, 995.5), substance use disorders (291, 292, 303–305, 327, 328), and other mental disorders (290, 293, 294, 301, 302, 306, 307, 310). In addition, an “other disorders” category was included for visits in which the primary diagnosis was not a mental disorder.

The survey includes a visit status variable that classifies patients according to whether the physician (or another physician in the same office) had ever seen the patient before. A psychotropic medication variable was constructed to capture whether a prescription was ordered, supplied, or administered at a visit for an antidepressant, antipsychotic, anxiolytic (including sedative hypnotics), a stimulant, or a mood stabilizer. A psychotherapy variable was defined to include any nonmedication treatment “designed to produce a mental or emotional response through suggestion, persuasion, reeducation, reassurance, or support” (9). In the 1995 survey, a variable indexed whether a patient was seen by a provider other than the psychiatrist, such as a nurse, physician’s assistant, or other health care professional. This information was not available for the 1985 survey.

Analysis Plan

We first examined the characteristics of psychiatric visits in both survey years to estimate secular change in patient composition and service delivery. We then examined the mean duration of psychiatric visits in the two survey periods, and for comparative purposes, we examined the mean duration of primary care visits (to family physicians, internists, and general practitioners) in the two surveys. To adjust for secular changes in patient characteristics, we combined the 1985 and 1995 surveys and used multiple linear regression to evaluate the association between survey year and visit duration, controlling for patient age, sex, race, expected payment source, visit status, diagnostic group, and psychotropic medication prescription.

We then determined the mean visit duration in each survey period, stratified by demographic group, expected payment source, visit status, diagnostic group, and psychotropic medication prescription. For each subgroup, multiple linear regression was used to estimate associations between survey year and visit duration, adjusting for other variables. The analysis excluded routine visits for methadone maintenance treatment of substance dependence. Such visits have not traditionally included direct patient contact with psychiatrists. A preliminary examination revealed that the sampled methadone maintenance visits uniformly included no face-to-face contact with the treating psychiatrist.

Statistical Methods

Because the visit sampling was not entirely random, the National Center for Health Statistics weighted each visit to correct for sampling imperfections. Reported percentages are based on the weighted estimates. The construction of weights has three components: 1) inflation by reciprocals of sampling probabilities, 2) adjustment for nonresponse, and 3) a ratio adjustment to fixed totals. The adjustment for nonresponse replaces patient visits to nonrespondents with visits to respondents in the same specialty and same primary sampling unit. The ratio adjustment involves multiplying each visit by the ratio of physicians listed in the American Medical Association–American Osteopathic Association master files for a given specialty over the number of sampled physicians in that specialty.

In consultation with the National Center for Health Statistics, a statistical adjustment was used to prepare the data for the multiple linear regressions. This adjustment involves reducing the effective sample size of the survey to simulate sampling from a simple random sample. The weights were multiplied by an adjustment factor calculated by dividing the sum of poststratification weights by the sum of the squared poststratification weights (10). This procedure yields conservative estimates that tend to overcompensate for stratification artifacts (11). Comparisons are considered statistically significant at the p=0.01 (two-tailed) level.

RESULTS

Change in Visit Characteristics

There were several significant differences between the background characteristics of psychiatric visits sampled in the 1985 and 1995 surveys. As compared with psychiatric visits in 1985, the 1995 survey included a substantially larger proportion of psychiatric visits by older patients, nonwhites, publicly insured patients, and patients who paid for their care through an HMO or other prepaid arrangements (table 1). A significantly larger percentage of the visits in the 1995 sample had a primary diagnosis of a depressive disorder (χ2=48.0, df=1, p<0.0001). In addition, a significantly larger percentage received a prescription for a psychotropic medication, and a smaller percentage received psychotherapy (table 1).

An analysis of the psychotropic medication visits revealed significant increases in the proportion with prescriptions for antidepressants (1985: 23.1%, versus 1995: 53.5%) (χ2=153.0, df=1, p<0.001), mood stabilizers (5.5% versus 10.1%) (χ2=11.7, df=1, p<0.001), and stimulants (1.4% versus 4.6%) (χ2=16.0, df=1, p<0.001). There was little change in the percentage of visits with a prescription for an antipsychotic (13.4% versus 13.4%) or an anxiolytic (20.7% versus 19.3%) medication. In 1995, selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) were prescribed in over half (59.4%) of the psychiatric visits that included an antidepressant prescription.

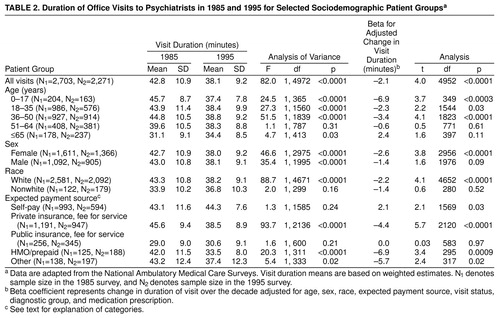

General Trends in Visit Duration

According to the National Ambulatory Medical Care Surveys, the mean duration of psychiatric visits declined from 42.8 minutes (SD=10.9) in 1985 to 38.1 minutes (SD=9.2) in 1995 (table 2). The analogous decline in the mean duration of visits to primary care physicians was not statistically significant (mean=15.3 minutes, SD=9.0, compared to mean=15.1 minutes, SD=10.4) (t=5.4, df=33, 718, n.s.).

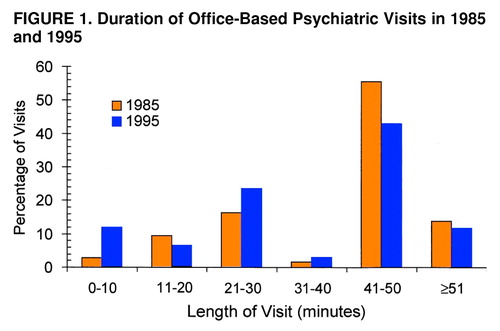

During this period, there was a significant increase in the proportion of surveyed psychiatric visits that were ≤10 minutes (2.9% versus 12.1%) (χ2=54.2, df=1, p<0.001) and 21 to 30 minutes in duration (16.4% versus 23.6%) (χ2=12.7, df=1, p<0.001) and a significant decrease in the proportion that were 41 to 50 minutes in duration (55.6% versus 43.0%) (χ2=23.5, df=1, p<0.001) (figure 1).

Visit Duration by Patient Demographic Group

In the univariate analysis, a significant reduction in mean visit duration occurred for visits by male and female patients, whites, and patients in the three youngest age groups. Among these groups, patients who were less than 18 years old experienced the largest decrease in mean visit duration (8.3 minutes). After control for the effects of other covariates, the decrease in visit duration remained significant for female patients, whites, and patients in the 0–17-year and 36–50-year age groups (table 2).

Visit Duration by Expected Payment Source

Privately insured fee-for-service patients and those in the HMO/prepaid group experienced significant decreases in mean visit duration during the study period. Both of these reductions remained statistically significant after adjusting for the confounding effects of the other covariates. The mean visit duration of self-paying patients and publicly insured patients remained essentially unchanged (table 2).

Visit Duration by Clinical Group

Patients who did not receive prescriptions for a psychotropic medication had significantly shorter visits in 1995 than in 1985 (table 3). During this period, however, there was not a significant change in the mean length of visits for patients who were prescribed a psychotropic medication (table 3). Subgroup analysis revealed that there was little change in the mean visit duration among patients prescribed each of the major classes of psychotropic medications: anxiolytics (1985: 38.4 minutes, versus 1995: 36.3 minutes), antidepressants (38.6 versus 37.4), antipsychotics (32.3 versus 31.1), stimulants (25.8 versus 39.7), or mood stabilizers (33.4 versus 33.3).

Patients who had been previously seen by the treating psychiatrist and patients who received psychotherapy during the visit received significantly shorter visits in 1995 than in 1985. These decreases in mean visit duration remained statistically significant after control for other clinical and demographic variables (table 3).

In the univariate analyses, several diagnostic groups were found to have a significant reduction in visit duration: depression, anxiety, bipolar, schizophrenia, childhood disorders or mental retardation, and the other mental disorder groups. After control for the other demographic and clinical variables, however, only visits with patients with childhood disorders or mental retardation remained significantly reduced in duration. It is surprising that there was a significant secular increase in visit duration for the small group of patients who received a primary substance use disorder diagnosis.

Co-Treatment

In the 1995 survey, 6.8% of the psychiatric visits included treatment from a health care professional other than the psychiatrist. The mean time spent with psychiatrists in these visits was significantly shorter than the time spent in visits that did not include co-treatment by another health care professional (26.5 minutes, SD=14.4, versus 38.9 minutes, SD=8.6) (t=66.1, df=2270, p<0.0001). More than one-third (39.2%) of the psychiatric visits that involved co-treatment included 10 minutes or less of face-to-face contact between the patient and the psychiatrist. If co-treatment visits are excluded from the 1995 survey, the mean difference in visit duration between the surveys becomes attenuated but remains significant (42.8 minutes, SD=10.9, versus 38.9 minutes, SD=8.6) (t=56.2, df=4,848, p<0.0001).

DISCUSSION

In the decade between 1985 and 1995, office-based psychiatrists tended to spend less time with each patient, provided psychotherapy in a smaller proportion of visits, and prescribed psychotropic medications in a larger proportion of visits. These changes are consistent with a trend toward the medicalization of psychiatric practice in the sense that the provision of psychotherapy and comparatively long visits have historically distinguished the mental health care provided by psychiatrists from that provided by other medical specialists. A secular trend toward shorter visits was not observed for visits to primary care physicians. These results suggest that in recent years office-based psychiatrists have become somewhat less extensively involved in the psychological dimensions of patient care and more involved in the prescription of psychotropic medications and psychiatric management.

The decline in visit duration was not evenly spread across all patient groups but tended to be most evident for those groups who had longer visits in the 1985 survey: younger patients, privately insured patients, and patients not prescribed psychotropic medication. By contrast, the patients who had previously received comparatively brief visits (i.e., older patients, publicly insured patients, and patients prescribed psychotropic medications) experienced little if any decrease in the duration of their psychiatric visits.

Although the average length of visits that included a prescription for a psychotropic medication did not significantly decline, the proportion of visits that included a psychotropic prescription markedly increased between the 1985 and 1995 surveys. As has been detailed elsewhere (12–14), this increase was closely related to the expanding use of a new generation of well-tolerated antidepressants. Because visits that include a prescription medication tend to be shorter than those without a prescription, an increase in the proportion of psychiatric visits that include a medication prescription tends to drive down the mean duration of all visits. In practice, effective psychiatric management may require a range of clinical skills, including establishing a therapeutic alliance, selecting an appropriate pharmacologic regimen, developing an overall treatment plan, monitoring the patient’s status over time, educating the patient concerning the illness and its treatment, and promoting adherence to treatment (15).

Changing market conditions may help explain the selective shortening of psychiatric visits for patient groups who had previously received relatively long visits. Data from the American Psychiatric Association’s 1996 National Survey of Psychiatric Practice indicate that discounted fee-for-service arrangements currently account for a substantial proportion of psychiatrists’ income (16). In order to meet income targets, which tend to change more slowly than actual income (17), psychiatrists who see patients at reduced private insurance visit fees may seek to compensate for the loss of income by shortening visit durations. Such economic considerations would also help explain why the duration of self-pay visits, which presumably have not come under fee constraints, did not change appreciably during the study period. The substantial decline in visit duration among HMO patients may be related to an increased application of cost-containment policies in this rapidly evolving and economically competitive sector.

One strategy psychiatrists may employ to maximize their economic efficiency is to work with a less highly paid health care professional who specializes in providing the more time-intensive psychotherapeutic aspects of treatment (18). In the 1995 survey, only about one in 15 visits to psychiatrists also included patient contact with another health care professional. As might be anticipated, psychiatrists tended to spend relatively little time in face-to-face contact with these patients.

The National Ambulatory Medical Care Surveys almost certainly underestimate the extent to which office-based psychiatrists treat patients who are also receiving mental health services from other providers. The survey measure of co-treatment captures only services provided during the same patient visit and so misses visits to other professionals that occur at some other time. Previous research indicates that psychiatrists commonly treat patients who receive mental health services from other health care professionals. In private practice, these arrangements may be initiated by a nonmedical therapist or a managed care firm, which seeks the psychiatrist to prescribe medication for the patient. Many psychiatrists have expressed ethical (19), practical, and clinical concerns regarding such shared treatment arrangements.

Beyond these economic and organizational considerations, important scientific advances, training factors, and ideological influences may have further contributed to changes in the way that office-based psychiatry is practiced (20). In the past decade and a half, the availability of new and effective psychotropic agents, including SSRI antidepressants and atypical neuroleptics (21), have opened up new treatment options. Clinical pharmacologic research has also identified new psychiatric indications for the anticonvulsants carbamazepine and valproate (22).

In response to the growing complexity of the psychopharmacologic knowledge base, psychiatric educators have assigned greater importance to teaching the clinical neurosciences and training young psychiatrists to appropriately prescribe and monitor psychotropic drugs, while emphasizing the more selective use of psychotherapy (23). At the same time, a growing body of evidence supports the efficacy of brief psychotherapy sessions for major depression, including interpersonal, cognitive, and behavioral approaches (24).

The National Ambulatory Medical Care Surveys are limited in many ways. They do not provide critical information on the number of visits in each episode of care or the frequency with which psychiatrists see patients during episodes. It is possible, although unlikely in our view, that the reported decrease in visit duration has been offset by a compensatory increase in the frequency or number of psychiatric visits by a given patient. Another limitation is the uncertain reliability of diagnoses established by practicing physicians and the effects of changes in the criteria used to diagnose mental disorders in 1985 (DSM-III) and 1995 (DSM-IV). Changes in the survey coding of expected source of payment may decrease the reliability of findings on this variable. It is also possible—although no change occurred in how the survey defined psychotherapy—that clinical concepts of what constitutes psychotherapy may have narrowed in a way that accounts for the decline in its reported use. A further limitation is that there is no information on the large number of psychiatrists who work outside of office-based practices (25). Furthermore, we cannot exclude the possibility that the observed changes in the patterns of care reflect a continuation of previous care combined with new groups of patients who have different clinical characteristics and needs. Finally, and perhaps most important, the surveys concern the experiences of psychiatrists, not patients. For this reason, it is impossible to discern from these data whether an average person is more or less likely to receive a given mental health service in 1995 than in 1985.

The portrait of office-based psychiatric practice that emerges from the present study is of a profession in transition. Visits are becoming shorter in length, psychotherapy is being used more selectively, and psychotropic medications are being prescribed in a larger proportion of visits. These changes may reflect psychiatry’s response to changing market forces and improvements in pharmacologic treatments.

Practice-based research has yielded valuable information. For example, it has provided evidence that major depression may be more effectively and efficiently treated by psychiatrists than primary care physicians (26) and in fee-for-service than prepaid settings (27). A new generation of practice-based research is needed to evaluate whether and to what extent emerging styles of psychiatric practice affect clinical outcomes.

Received Nov. 3, 1997; revisions received March 23, June 19, and Aug. 3, 1998; accepted Aug. 25, 1998. From the New York State Psychiatric Institute/Department of Psychiatry and the Western Psychiatric Institute and Clinic, Pittsburgh, Pa. Address reprint requests to Dr. Olfson, New York State Psychiatric Institute/Department of Psychiatry, College of Physicians and Surgeons of Columbia University, 1051 Riverside Dr., New York, NY 10032. Supported by a grant from the Van Ameringen Foundation to the American Psychiatric Association.

|

|

|

FIGURE 1. Duration of Office-Based Psychiatric Visits in 1985 and 1995

1. Detre T, McDonald MC: Managed care and the future of psychiatry. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1996; 334:131–135Google Scholar

2. Bernstein DB: Does managed care permit appropriate use of psychotherapy? Psychiatr Serv 1996; 47:971–974Google Scholar

3. Meyer RE, Sotsky SM: Managed care and the role and training of psychiatrists. Health Aff 1995; 14:65–66Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

4. Schreter RK: Coping with the crisis in psychiatric training. Psychiatry 1997; 60:51–59Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

5. Knesper DJ, Pagnucco DJ, Wheeler JR: Similarities and differences across mental health service providers and practice settings in the United States. Am Psychologist 1985; 40:1352–1369Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

6. Schurman RA, Kramer PD, Mitchell JB: The hidden mental health network: treatment of mental illness by nonpsychiatrist physicians. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1985; 42:89–94Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

7. Olfson M, Goldman HH: Psychiatric outpatient practice: patterns and policies. Am J Psychiatry 1992; 149:1492–1498Link, Google Scholar

8. Schappert SM: National Ambulatory Medical Care Survey: 1994 Summary: Advance Data From Vital and Health Statistics, number 273. Hyattsville, Md, National Center for Health Statistics, 1996Google Scholar

9. Public Use Data Tape Documentation: 1985 National Ambulatory Medical Care Survey. Hyattsville, Md, National Center for Health Statistics, 1987Google Scholar

10. Potthoff RF, Woodbury MA, Manton KG: “Equivalence sample size” and “equivalent degrees of freedom” refinements for inference using survey weights under superpopulation models. J Am Statistical Assoc 1992; 87:383–396Google Scholar

11. Robins LN, Regier DA (eds): Psychiatric Disorders in America: The Epidemiological Catchment Area Study. New York, Free Press, 1991Google Scholar

12. Olfson M, Klerman GL: Trends in the prescription of antidepressants by office-based psychiatrists. Am J Psychiatry 1993; 150:571–577Link, Google Scholar

13. Olfson M, Marcus S, Pincus HA, Zito JM, Thompson JW, Zarin DA: Antidepressant prescribing practices of outpatient psychiatrists. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1988; 55:310–316Google Scholar

14. Olfson M, Klerman GL: Trends in the prescription of psychotropic medications: the role of physician specialty. Med Care 1993; 31:559–564Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

15. American Psychiatric Association: Practice Guideline for the Treatment of Patients With Bipolar Disorder. Am J Psychiatry 1994; 151(Dec suppl)Google Scholar

16. Zarin DA, Pincus HA, Peterson BD, West JC, Suarez A, Marcus SC: Characterizing psychiatry with findings from the 1996 National Survey of Psychiatric Practice. Am J Psychiatry 1998; 155:397–404Link, Google Scholar

17. Rizzo JA, Blumenthal D: Physician income targets: new evidence on an old controversy. Inquiry 1994–1995; 31:394–404Google Scholar

18. Schreter RK: Essential skills for managed behavioral health care. Psychiatr Serv 1997; 48:653–658Link, Google Scholar

19. Goldberg RS, Riba M, Tasman AL: Psychiatrists’ attitudes toward prescribing medication for patients treated by nonmedical psychotherapists. Hosp Community Psychiatry 1991; 42:276–280Abstract, Google Scholar

20. Pincus HA, Tanielian TL, Marcus SC, Olfson M, Zarin DA, Thompson J, Zito JM: Prescribing trends in psychotropic medications: primary care, psychiatry and other medical specialties. JAMA 1998; 279:526–531Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

21. Lieberman JHA: Atypical antipsychotic drugs as a first-line treatment of schizophrenia: a rationale and hypothesis. J Clin Psychiatry (Suppl) 1996; 11:68–71Google Scholar

22. Post RM, Ketter TA, Denicoff K, Panzzaglia PJ, Leverich GS, Marangell LB, Callahan AM, George MS, Frye MA: The place of anticonvulsant therapy in bipolar disorder illness. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 1996; 128:115–129Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

23. Beigel A, Santiago JM: Redefining the general psychiatrist: values, reforms, and issues for psychiatric residency education. Psychiatr Serv 1995; 46:769–774Link, Google Scholar

24. Weissman MM: Psychotherapy in the maintenance treatment of depression. Br J Psychiatry (Suppl) 1994; 26:42–50Medline, Google Scholar

25. Olfson M, Pincus HA, Dial TH: Professional practice patterns of US psychiatrists. Am J Psychiatry 1994; 151:89–95Link, Google Scholar

26. Sturm R, Wells KB: How can care for depression become more cost-effective? JAMA 1995; 273:51–58Google Scholar

27. Rogers WH, Wells KB, Meredith LS, Sturm R, Burnam A: Outcomes for adult outpatients with depression under prepaid or fee-for-service financing. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1993; 50:517–525Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar