Double-Blind Study of Clozapine Dose Response in Chronic Schizophrenia

Abstract

OBJECTIVE: This study explored the relative efficacy of three different doses of clozapine. METHOD: Fifty patients who met Kane et al.’s criteria for treatment-refractory schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder were studied. All subjects were randomly assigned to 100, 300, or 600 mg/day of clozapine for 16 weeks of double-blind treatment. Forty-eight patients completed this first 16 weeks. Of the 50 patients, 36 went on to second and third 16-week trials of double-blind treatment at the remaining doses. RESULTS: Four subjects (8%) responded to the first 16-week condition, and one subject (2%) responded to the next 16-week crossover condition. A chi-square comparison of the response rates from the three dose groups failed to show a significant effect. An analysis of variance (ANOVA) comparison of Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale—Anchored (BPRS-A) total change scores from baseline to last observation carried forward showed a significant dose effect (600>300>100 mg/day) at 16 weeks of treatment. A crossover ANOVA of the BPRS-A total scores from the 48-week study also showed that the main effect for dose was highly significant; the 100-mg/day dose gave the higher (poorer) values, and the 300- and 600-mg/day doses gave equal (better) values. Gender played a role in clinical response to treatment at 100 mg/day. CONCLUSIONS: Clozapine treatment at 100 mg/day was less effective than at 300 or 600 mg/day. At 100 mg/day, women responded better than did men. The 600 mg/day group had the best results, but an occasional patient required up to 900 mg/day. Overall response rates were lower than expected.

The introduction of chlorpromazine by Delay and Deniker (1) represented a major advancement in the treatment of schizophrenia and other psychoses. In the following 20 years, other, similar neuroleptic agents with different chemical structures became available. Some were more potent than others, but all shared a common mechanism of action that centered on dopamine 2 receptor antagonism. None appeared to be superior to the others in terms of clinical efficacy, and all of the neuroleptics produced an array of distressing extrapyramidal symptoms that varied in form and severity. These early antipsychotic drugs were introduced without systematic multiple-dose studies, and, unfortunately, it took many years to understand that high equivalent doses were associated with more side effects and, in some cases, a poorer treatment response (2).

Clozapine was initially tested in the 1970s (3) and represented the beginning of a new generation of antipsychotic agents. Early U.S. studies suggested that clozapine had an atypical side effect profile; it appeared not to produce extrapyramidal side effects such as tardive dyskinesia and akathisia. It was associated with a higher risk for agranulocytosis. The drug was also associated with a higher risk of seizures; this risk seemed to be related to dose or plasma level . The paradoxical effect of hypersalivation was also observed. While clozapine was not marketed in the United States because of the risk for agranulocytosis, it continued to be used in some European countries with success.

In a landmark study, Kane et al. (5) showed that 30% of the patients with schizophrenia with treatment-refractory psychotic symptoms responded to clozapine, whereas only 4% of comparable patients responded to chlorpromazine. The Kane et al. study was important for several reasons. 1) It was the first study to show that one neuroleptic drug was significantly more effective than another in treating positive psychotic symptoms. 2) The study suggested that clozapine treatment may be associated with improvement of the negative symptoms of psychosis. 3) Finally, and perhaps most important, the Kane et al. study showed that a significant proportion of the patients with the treatment-refractory symptoms of schizophrenia responded to clozapine, although all of the patients had been resistant to prior treatment with at least three neuroleptic agents.

The Kane et al. study led to worldwide interest in clozapine, treatment-refractory schizophrenia, and the development of other atypical neuroleptic agents. When clozapine was reintroduced into the United States, little was known about either the optimal dose or optimal length of treatment. However, it soon became clear that, as with earlier neuroleptic agents, U.S. psychiatrists tended to use higher clozapine doses than did European psychiatrists (6). The Kane et al. 6-week study used flexible dosing up to 900 mg/day of clozapine, with mean peak doses exceeding 600 mg/day. Longer treatment trials were suggested by Meltzer (7), who found in an open study that 6 months of clozapine treatment yielded a 50% response rate. A recent double-blind study by Rosenheck et al. (8) suggested a lower response rate for clozapine than that reported by either Kane et al. or Meltzer and a higher response rate for the typical neuroleptic haloperidol. The respective response rates at 6 weeks for clozapine and haloperidol were 24% and 13%, and 37% and 32% after 1 year, respectively.

Our study was designed to provide information about the appropriate dose of clozapine. In a double-blind manner, we examined patients with treatment-refractory schizophrenic symptoms in an initial trial of at least 4 months, using three different clozapine doses: 100, 300, and 600 mg/day. Patients who completed the 4-month study but did not respond to clozapine were further studied with the two other double-blind clozapine doses, each for a 4-month period.

METHOD

Subjects

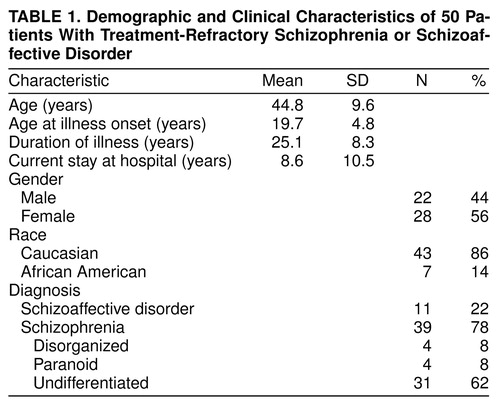

Fifty individuals with chronic psychosis were either recruited or referred for clozapine treatment from a large population of state hospital patients. The Kane et al. (5) criteria were followed for selecting patients with treatment-refractory symptoms of schizophrenia. All subjects 1) met the DSM-III-R criteria (verified by the Structural Clinical Interview for DSM-III-R) for either schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder; 2) had not shown satisfactory clinical response to treatment with at least three neuroleptic drugs (each given for at least 6 weeks in doses equivalent to 1000 mg/day of chlorpromazine); 3) had Clinical Global Impression (CGI) (9) scale ratings of moderately ill; and 4) had Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale—Anchored (BPRS-A) (10) total scores of at least 45, with ratings of moderately ill on at least two of the four BPRS-A positive symptoms (i.e., hallucinatory behavior, conceptual disorganization, unusual thought content, and suspiciousness). table 1 shows the demographic and clinical characteristics for the entire study group. The current hospital stay ranged from 1 to 38 years; the group had an estimated median of five psychiatric hospitalizations (range=1–25). The duration of the current hospitalization was inversely related to the number of hospitalizations (e.g., two patients had single documented hospitalizations of 35 and 38 years). In short, the selected experimental group had severe treatment-refractory symptoms that had affected their individual lives for a quarter of a century or more and precipitated numerous psychiatric hospitalizations.

Design

Overview of the 16-week cross-sectional trial. All patients signed informed consent forms and were transferred to the 32-bed research unit of the Norristown State Hospital Clinical Research Center, where they adapted to their new environment for at least 4 weeks without any modifications in their medication regimens. During this adaptation period (the naturalistic baseline), weekly systematic evaluations of psychopathology were initiated; these continued throughout the remainder of the 16 weeks of study. The evaluations included the BPRS-A, the CGI scale, and the Scale for the Assessment of Negative Symptoms (SANS) (11) for psychopathology.

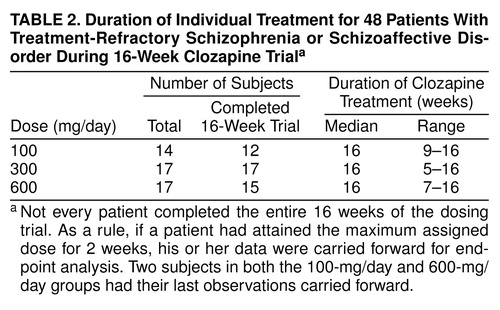

After this naturalistic baseline period, an attempt was made to place all patients on a regimen of 10 mg/day of haloperidol treatment (haloperidol phase) for an additional 4 weeks as both a direct test for treatment response and as a standardized preparation for clozapine treatment. Of the 50 subjects, 44 entered the haloperidol phase, and none showed clinical improvement; in fact, on average, the group showed a worsening of symptoms. The other six patients did not enter the haloperidol phase, either because of prior sensitivity to haloperidol or because there were problems managing them on the ward. These six continued their naturalistic baseline treatment (fluphenazine: N=3, chlorpromazine: N=2, thioridazine: N=1). At the conclusion of the haloperidol phase, all subjects were randomly assigned to one of the three dose groups for 16 weeks of double-blind treatment. Briefly, this was a cross-sectional trial wherein each patient was randomly assigned to one dose of clozapine. table 2 provides details for each of the three dose groups. There was no placebo control group in this investigation.

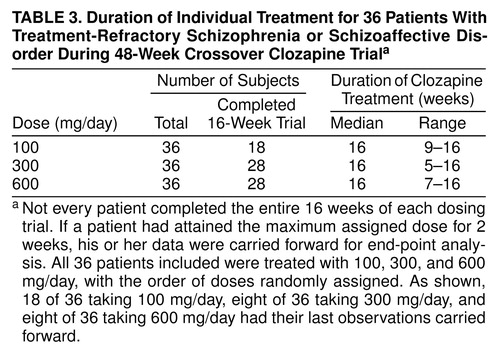

Overview of the 48-week longitudinal design. Throughout the initial 16-week study, all patients were evaluated for treatment response. Following the procedures of Kane et al., treatment responders were defined as those who had either CGI scores of less than 3 or BPRS-A total scores of less than 35 and who showed 20% reductions in their BPRS-A total scores between their naturalistic baseline ratings and their ratings from the 16th week of the trial. Responders were either discharged from the hospital or transferred to another unit where their treatment was switched to open use of clozapine without disclosure of doses. Those judged to be nonresponders were offered the opportunity to continue in another 16-week, double-blind clozapine trial in a balanced crossover trial with one of the two other study doses. If treatment failure again occurred during these 16 weeks, a third 16-week treatment period was offered to the subjects, using the final study dose. Therefore, in this 48-week study, a patient could participate in a series of three 16-week trials, receiving double-blind clozapine treatment with all three study doses. For administrative reasons, the first 10 subjects were not eligible to continue after the original 16-week trial. Of the remaining 40 patients, 36 patients began and completed the entire 48-week, double-blind study. table 3 provides details for each of the three dose groups.

Double-blind titration schedule. All subjects received the same number of identical capsules each morning and each afternoon. An initial dose of 25 mg was administered on the first day, 50 mg on each of the second and third days (divided equally between morning and evening doses), 75 mg on each of the fourth and fifth days (divided into a 25-mg dose in the morning and a 50-mg dose in the evening), and 100 mg on each of the sixth and seventh days (divided into a 25-mg dose in the morning and a 75-mg dose in the evening). The dose was then titrated upward by 100 mg per week for the first 3 weeks and thereafter at a rate of 200 mg per week until the assigned double-blind dose was achieved. Thus, those patients who were randomly assigned to 100 mg/day of clozapine achieved the assigned dose by the end of the first week, whereas those randomly assigned to 300 mg/day or 600 mg/day of clozapine achieved the assigned dose by the end of the third and fifth weeks, respectively. To decrease a dose when necessary for a subsequent 16-week trial, the dose was titrated downward at a rate and in increments identical to the rate and increments of the dose increases.

Definitions of dropouts and completers. Any patient who withdrew from the study because of adverse effects or medical complications before 2 weeks of active clozapine treatment was classified as a dropout and was not considered in any analysis. Patients who experienced a worsening of symptoms during any 16-week treatment phase were monitored closely. A decision could have been made to discontinue the current dose and move on to the next 16-week treatment phase. Any patient who received his or her randomly assigned dose of clozapine for 2 weeks was considered a completer, and his or her last observation was carried forward for end-point analysis. The only noncompleters in the first 16-week trial were two patients who withdrew from the study for medical reasons (ruptured appendix and intestinal resection).

Evaluations

The BPRS-A, CGI, and SANS scale scores were assessed by four research psychiatrists or senior fellows who were blind to clozapine doses (J.K.S., J.d.L., C.N., and A.O.-W.). During the baseline, haloperidol, and first clozapine phases, ratings were assessed weekly. During subsequent 16-week treatment phases, ratings were assessed monthly. Each rater followed his or her assigned patients through all of the 16-week phases. The reliability of the ratings was monitored in two ways. 1) Weekly patient rating sessions were conducted by using either hospital patients or training tapes (including recommended anchor points), followed by a detailed discussion by all raters. Informal interrater reliability was computed each week, and any drift or discrepancies in ratings were discussed. 2) After 6 months and then at 1-year intervals, formal intraclass correlation coefficients (ICC) (12) were computed for the BPRS-A total scores. ICCs were 0.85, 0.89, and 0.92 for the raters.

Statistical Analysis

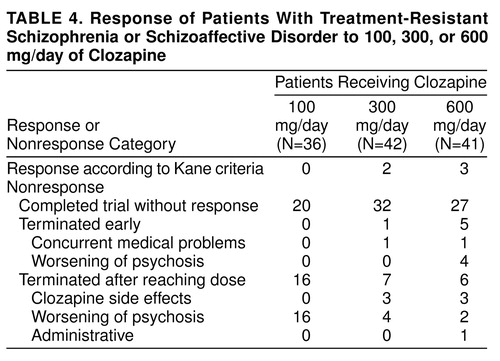

Patients were included in the statistical analyses even if they did not complete a full 16-week treatment period. If a patient had received his or her randomly assigned treatment dose for 2 weeks but could not continue because of severity of symptoms, his or her last available observation was carried forward for analysis. table 2 and table 3 indicate the duration of clozapine treatment for both the 16- and 48-week treatment phases. table 4 combines the treatment responses across all 48 weeks. SPSS 7.5 for Windows was used to perform all statistical analyses, with the exception of the crossover analysis of variance (ANOVA) of the 48-week data set. All significance tests were performed by using two-tailed probabilities with an alpha level of 0.05.

Data were grouped in two ways for statistical analysis. The first group consisted of all patients who completed the initial 16 weeks of clozapine treatment. Of the original 50 patients recruited, 48 were deemed to have completed the initial 16-week, double-blind treatment phase and were included in the analysis. Of these, 44 subjects (92%) had actually completed the entire 16-week treatment period; four had data carried forward. The second group consisted of all patients who completed the first 16 weeks of clozapine treatment plus the two additional 16-week treatment periods. Of the original 50 patients, 36 completed the entire 48-week study and were included in the analysis. These groups are referred to as the 16- and 48-week data sets.

The 16-week data set was analyzed in several ways. Initially, a chi-square analysis of response rates was performed with patients categorized as responders or nonresponders following the criteria of Kane et al. Next, mean BPRS-A total score change from the naturalistic baseline to the last observation carried forward was evaluated. Total scores were computed by using all individual BPRS-A items. The univariate ANOVA model included one between-subject factor—group (three levels: 100 mg/day, 300 mg/day, and 600 mg/day). Post hoc pairwise comparisons were performed by using Tukey’s honestly significant difference test. Finally, an exploratory ANOVA model included two between-subject factors—group (three levels: 100 mg/day, 300 mg/day, and 600 mg/day) and gender (two levels)—including the group-by-gender interaction.

The 48-week analytic approach was modified. Here, a crossover analysis of variance design (four by three) as described by Kirk (13) was used because all 36 subjects appeared in each of the three dose groups. Each patient was randomly assigned to the first dose and then received second and third treatment doses. In the crossover ANOVA design, four dependent variables were entered into the model (clozapine week 4, 8, 12, and 16 BPRS-A total scores from each dosing period) as a within-subject factor (time), along with another within-subject factor—group (three levels: 100 mg/day, 300 mg/day, and 600 mg/day). The crossover model assumed that there were no interactions.

RESULTS

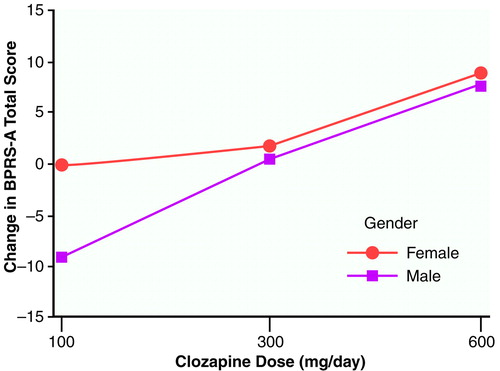

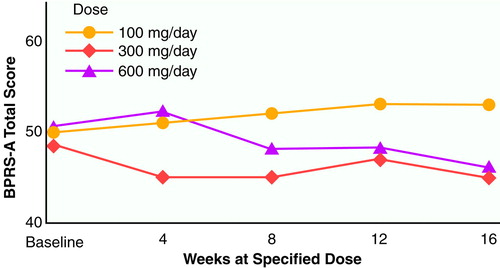

None of the patients responded to treatment with haloperidol, confirming the selection of patients with treatment-refractory symptoms for this study. It is interesting that, as shown in table 5, many of them showed a worsening of symptoms during the standardized lead-in period with haloperidol treatment. When we used the criteria of Kane et al., four patients (8%) responded to the first clozapine dose and one subject (2%) to the next clozapine dose. None of the patients responded to the third clozapine dose. Of the five responders, two subjects responded to a dose of 300 mg/day, three to 600 mg/day, and none to 100 mg/day. A chi-square test comparing rates of responders and nonresponders during the first 16-week period across the three dose groups was nonsignificant (χ2=3.5, df=2, n.s.).

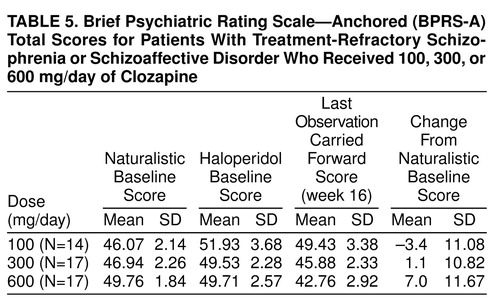

Results of the 16-week study (N=48). Mean BPRS-A total scores across the first full 16-week study are displayed in figure 1. table 5 summarizes mean scores. No significant naturalistic baseline differences were observed between the treatment groups. Levene’s test of equality of error variance showed that the error variance for the change scores from the naturalistic baseline to the last observation carried forward was equivalent across groups (F=0.05, df=2, 45, p>0.93). An ANOVA of between-group differences in BPRS-A total change scores from baseline to the last observation carried forward revealed a statistically significant dose effect (F=3.35, df=2, 45, p<0.04). Two-way comparisons by means of Tukey’s honestly significant difference test (p<0.05 criterion) revealed that the 600-mg/day group had a better clinical response than the 300-mg/day and 100-mg/day groups. The comparison between the 300-mg/day and 100-mg/day groups failed to reach statistical significance (p=0.13).

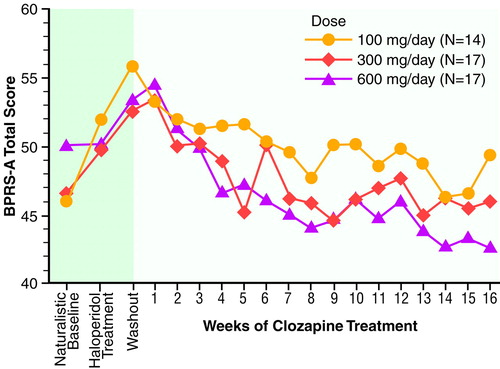

We wondered whether gender contributed to the overall variance in a systematic fashion. Therefore, another ANOVA was performed with both group (three levels: 100 mg/day, 300 mg/day, and 600 mg/day) and gender (two levels) as main effects, as well as the group-by-gender interaction. First, Levene’s test of equality of error variance showed that the error variance with gender included was equivalent across groups (F=0.74, df=5, 41, p>0.64). In an ANOVA of between-group differences from baseline to the last observation carried forward, a significant group effect was again obtained (F=5.08, df=2, 41, p<0.01). Gender was not statistically significant (F=1.54, df=1, 41, p>0.22), and the group-by-gender interaction failed to reach statistical significance (F=0.56, df=2, 41, p>0.57). Two-way comparisons by means of Tukey’s honestly significant difference test again revealed that the 600-mg/day group had a better clinical response than both the 300-mg/day (p<0.14) and 100-mg/day (p<0.01) groups. The difference between the 300-mg/day and 100-mg/day groups failed to reach statistical significance (p=0.51). Figure 2 plots the mean BPRS-A total change scores across dose groups with scores separated by gender. It is interesting that for the 100-mg/day dose, a difference in clinical response was observed between men and women (women responded more than men), which was not seen for the other two doses.

Results of the 48-week study (N=36). Mean BPRS-A total scores across the entire 48-week study are shown in figure 3. Each of the three dosing phases across the 48 weeks were 16 weeks in length, with data from each dosing period represented as week 4, 8, 12, or 16. This analysis included a total of 36 subjects. In the crossover analysis, the main effect for group was highly significant (F=9.91, df=2, 34, p<0.0001), with the 100-mg/day dose showing the highest (poorest) values and the values of the 300-mg/day and 600-mg/day doses being approximately equal. The main effect for time was also significant (F=6.47, df=3, 34, p<0.01). There was no group-by-time interaction term in this crossover model.

Because of the limited range of response, no attempt was made to study the relationships of plasma levels of clozapine. At a descriptive level, however, all responders had levels that were greater than 350 ng/ml of clozapine (not including norclozapine). Extrapyramidal symptom results from this group have been reported elsewhere and essentially showed that clozapine did not cause rigidity or akathisia (14, 15).

DISCUSSION

A group of state hospital patients was treated with three different doses of clozapine in a 48-week, double-blind study. The study initially began as a 16-week cross-sectional investigation (N=48) that was extended into a 48-week longitudinal study (N=36), with individual patients receiving a trial with each of the three doses (16 weeks each). The number of patients who improved to the point that they were judged to be responders by using the Kane et al. criteria was small compared to other studies of the efficacy of clozapine. If we consider all the patients treated across the entire 48-week, double-blind study, approximately 10% (five of 48) demonstrated sufficient clinical improvement to be considered treatment responders. Four additional patients responded to clozapine when they received open medication at higher doses (800–900 mg/day), but even adding these additional patients brought the number of responders to only 19% (nine of 48). Clearly, these results, based on the Kane et al. response criteria, are at variance with the bulk of the findings on clozapine efficacy.

The reasons for this lower response rate are not clear, but several factors need to be considered. 1) The patients enrolled in this study were chronically ill, perhaps more chronically ill than other groups reported in the literature. 2) The Kane et al. criteria for treatment response are categorical and, perhaps, insensitive to modest clinical gains. 3) The demonstration of clinical response was strongly influenced by the choice of baseline measure. 4) The raters may have been highly conservative in their assessment of symptoms across time. Each of these possibilities will be considered in turn.

The first relates to the general problem of patient selection and subject variance across hospital sites. As shown in table 1, for our group, mean age was 44.8 years; mean duration of illness was 25.1 years. The mean duration of the current hospitalization was 8.6 years (range=1–38); the group had an estimated median of five hospitalizations (range=1–25). The pivotal Kane et al. sample of 319 patients (5) was nearly a decade younger; the mean age was 35.7 years. The Lindenmayer et al. sample (16) had a mean age of 34 years and a duration of illness of 15 years, and the Lieberman et al. (17) study group had a mean age of 28 years and a duration of illness of 9 years. Clearly, the patients enrolled in this study were older and extremely chronically ill, indeed, to our knowledge, more chronically ill than other subject groups reported to date. Lieberman et al. (17) found poorer clozapine response was associated with age at onset (19 years or less) and, to a lesser extent, duration of illness (9 or more years). In addition, at the time of our study, treatment with clozapine had commenced in the state hospital. More than 100 state hospital patients had already begun treatment with clozapine and, therefore, were not eligible for our study. This biases our study group in the sense that the majority of the remaining patients were much more difficult to manage clinically and many had additional comorbid medical problems. Perhaps these opaque subject factors combined to result in a lowering of the rate of clinical response.

The second possibility relates to the issue of defining treatment response. According to Kane et al., the a priori definition of treatment response to clozapine is categorical: patients with either a CGI of less than 3 or a BPRS-A total score of less than 35 who showed a 20% reduction in their BPRS-A total score. It is possible that some of our chronically ill patients responded to clozapine at a level that was clinically meaningful but was below the threshold of improvement sufficient to meet these a priori criteria. This would be consistent with general clinical observations that the majority of patients treated with clozapine, who are not terminated because of side effects, tend to improve according to ward staff and relatives, although these impressions are often found to be made on the basis of an improved level of social function, a reduction in level of aggression, and fewer periods of isolation and restraint. Our group showed a significant decline in BPRS-A total scores across both the 16-week and the 48-week evaluations, although the level of improvement was below the Kane et al. threshold. It is not surprising that a preliminary analysis of part of these data with less stringent response criteria showed much more of a response rate than reported here (18).

A third possible reason for the low response rate may relate to the issue of baseline selection. With treatment response partly defined as a 20% reduction in the BPRS-A total score, the initial baseline calibration of symptom severity is critical. This baseline selection strongly influences the determination of treatment efficacy. In our design, two legitimate baselines were available. The first option was the naturalistic baseline, and the second option was the haloperidol baseline; the 1-week washout was not considered a valid baseline. Examination of figure 1 and table 5 shows that symptom severity at these two potential baselines was different. Group BPRS-A total scores worsened when patients were placed on 4 weeks of haloperidol treatment as compared to the naturalistic baseline. When an exploratory ANOVA was performed by using BPRS-A total change from haloperidol baseline to last observation carried forward, it was interesting that the basic results did not change although the magnitude of BPRS-A changes scores was greater. On close inspection, the absence of greater statistical significance resulted from a twofold increase in the level of variance between the naturalistic baseline and the haloperidol baseline. The switch to haloperidol as a standardized lead-in to the clozapine treatment significantly increased the level of “noise” in the data. We compared the efficacy of clozapine against the real-life level of clinical care within this state hospital. It may be the case that research designs requiring patients to be switched to some standardized neuroleptic (such as haloperidol) may artificially worsen the clinical condition of the study group at baseline and thus inflate the actual effects of the treatment. Akathisia was present in fewer than 20% of the subjects during the natural baseline but in over 40% of the subjects after 4 weeks of haloperidol treatment, 10 mg/day.

A fourth possible reason for the low response rate may relate to our raters being highly conservative in their ratings of symptoms across time. Admittedly, the study was done within the context of a large state hospital, where the expectations for clinical improvement are often modest. While acknowledging that our raters may have adopted modest expectations for clinical improvement, it is worth noting that all ratings were on the basis of defined anchor points. Moreover, weekly group ratings were performed and scores were discussed by all raters by using a heterogeneous selection of inpatients, outpatients, and training tapes in an effort to guard against various kinds of rater drift.

On the basis of the negative findings of treatment response by using the Kane et al. criteria, it is tempting to assume that the results shed little light on the question of clozapine dose response. However, this was not the case. When we used the Kane et al. criteria, no patient responded to 100 mg/day of clozapine. Indeed, almost 50% of the patients at this dose had a worsening of their psychosis and had to be terminated from this phase of the study. In contrast, only 9% of the patients were terminated from the 300-mg/day dose, whereas 4% were terminated from the 600 mg/day dose for a worsening of their psychosis. On the basis of the ANOVA results of both the 16- and 48-week data sets, we were able to conclude that there was a statistically significant dose response. In the case of the 16-week data, there was a significant difference between 600-mg/day response and response from the other two doses; however, in the 48-week data set, the 300-mg/day and 600-mg/day responses were equivalent; both were better than the 100-mg/day response. The small group size precluded the establishment of any relationships between clozapine blood levels and clozapine response. However, all patients who did respond had blood levels in the range of 350 ng/ml of clozapine. Notably, one subject required 900 mg/day to reach this value.

It is interesting that the cross-sectional 16-week analysis yielded more statistically powerful findings of a dose effect than was found in the 48-week crossover analysis. In general, when patients are used as their own control subjects in a repeated-measures design, the dose response effect is stronger. However, with this data set, the crossover design introduced uncontrolled sources of variance, such as carryover effects from the previous dose and time, and these could not be systematically partitioned in our analysis. Nonetheless, we are not aware of any other multiple-dose, double-blind studies. A recent 12-week, double-blind clozapine study investigated patients with low (50–150 ng/ml), medium (200–300 ng/ml), or high (350–450 ng/ml) blood levels of clozapine that were achieved with mean doses of 165, 373, and 511 mg/day, respectively (19). This study suggests that therapeutic blood levels are higher than 250 ng/ml (mean dose=373 mg/day) when using equally divided doses and blood drawn approximately 12 hours after the last dose. Prior studies using an evening dose or blood drawn in less than 12 hours after clozapine administration recommended higher blood levels. Hasegawa et al. (20) recommended 370 ng/ml (mean dose=385 ng/ml), Perry et al. (21) recommended 350 ng/ml (mean dose=384 mg/day), Potkin et al. (22) recommended 420 mg/ml (mean dose=400 mg/day), and Kronig et al. (23) recommended 350 ng/ml (mean dose=484 mg/day). Therefore, it appears that the average patient needs to be treated with at least 300–600 mg/day of clozapine to achieve a therapeutic response. It is also clear that some patients need higher doses to obtain this response.

Received Aug. 17, 1998; revision received April 14, 1999; accepted May 4, 1999. From the Medical College of Pennsylvania/Hahnemann University, Philadelphia, and the Norristown State Hospital, Pa. Address reprint requests to Dr. Simpson, Department of Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences, Keck School of Medicine, University of Southern California, 1937 Hospital Place, GRH 240, Los Angeles, CA 90033; [email protected] (e-mail). Supported in part by U.S. Public Health Service grant MI-145190, Novartis Pharmaceuticals Corporation, and a National Alliance for Research on Schizophrenia and Depression Established Investigator Award to Dr. Simpson. The authors thank the staffs of Haverford State Hospital and Norristown State Hospital Clinical Research Center for patient care; R. Eduardo Antelo, M.D., Cherian Verghese, M.D., Phyllis Rosen, M.S.W., Eileen M. McCann, R.N., and Amy McGrory for recruiting and rating patients; Susan Jensen for editorial assistance; and Albert R. DiDario for administrative support and encouragement.

|

|

|

|

|

FIGURE 1. BPRS-A Total Scores During 16 Weeks of Clozapine Treatment for Patients With Schizophrenia or Schizoaffective Disorder

FIGURE 2. BPRS-A Total Change Scores for 36 Patients With Schizophrenia or Schizoaffective Disorder From Naturalistic Baseline to Last Observation Carried Forward With Three Different Clozapine Dosesa

Although the interaction did not reach statistical significance, it is interesting that the curves for men and women are equivalent at the 300-mg/day and 600-mg/day doses. While taking the 100-mg/day dose, the women, on average, showed no change, whereas the men, on average, worsened.

FIGURE 3. BPRS-A Total Scores for 36 Patients With Schizophrenia or Schizoaffective Disorder Who Were Treated for 48 Weeks With Three Different Clozapine Dosesa

aEach dosing phase was 16 weeks in length, and the designation of weeks 4, 8, 12, and 16 refers to time on a specific dose of clozapine. The order of the three dose groups was randomly assigned. The baseline measure designated in the figure is the naturalistic period before the start of clozapine treatment; the haloperidol baseline is excluded.

1. Delay J, Deniker P: Le traitement des psychoses par une methode neurolytique derivée d’hibemotherapie; le 4560 RP utilisée seul en cure prolongée et continuée. Congrès Des Médecins Alienistes et Neurologistes de France et des Pays du Langue Française 1952; 50:503–513Google Scholar

2. Baldessarini RJ, Cohen BM, Teicher ME: Significance of neuroleptic dose and plasma level in the pharmacological treatment of psychoses. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1988; 45:79–91Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

3. Simpson GM, Varga E: Clozapine—a new antipsychotic agent. Curr Ther Res 1974; 18:679–686Google Scholar

4. Simpson GM, Cooper TB: Clozapine plasma levels and convulsions. Am J Psychiatry 1978; 135:99–100Link, Google Scholar

5. Kane J, Honigfeld G, Singer J, Meltzer H: Clozapine for the treatment-resistant schizophrenic: a double-blind comparison with chlorpromazine. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1988; 45:789–796Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

6. Pollack S, Lieberman JA, Fleischhacker WW, Borenstein M, Safferman AZ, Hummer M, Kurz M: A comparison of European and American dosing regimens of schizophrenic patients on clozapine: efficacy and side effects. Psychopharmacol Bull 1995; 31:315–320Medline, Google Scholar

7. Meltzer HY: Duration of a clozapine trial in neuroleptic-resistant schizophrenia (letter). Arch Gen Psychiatry 1989; 46:672Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

8. Rosenheck R, Cramer J, Xu W, Thomas J, Henderson W, Frisman L, Fye C, Charney D: A comparison of clozapine and haloperidol in hospitalized patients with refractory schizophrenia. N Engl J Med 1997; 337:809–815Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

9. Guy W (ed): ECDEU Assessment Manual for Psychopharmacology: Publication ADM 76-338. Washington, DC, US Department of Health, Education, and Welfare, 1976, pp 218–222Google Scholar

10. Woerner MG, Mennuzza S, Kane JM: Anchoring the BPRS-A: an aid to improved reliability. Psychopharmacol Bull 1988; 24:112–117Medline, Google Scholar

11. Andreasen NC: Scale for the Assessment of Negative Symptoms (SANS). Iowa City, University of Iowa, 1981Google Scholar

12. Shrout PE, Fleiss JL: Intraclass correlations: uses in assessing rater reliability. Psychol Bull 1979; 86:420–428Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

13. Kirk RE: Experimental Design: Procedures for the Behavioral Sciences, 3rd ed. Pacific Grove, Calif, Brooks/Cole, 1995Google Scholar

14. Nair CJ, de Leon J, Simpson GM, Josiassen RC: Therapeutic effects of clozapine on tardive dyskinesia. Cognitive and Behavioral Practice 1998; 5:119–127Crossref, Google Scholar

15. Nair CJ, Josiassen RC, Abraham G, Stanilla JK, Tracy JI, Simpson GM: Does akathisia influence psychopathology in psychotic patients treated with clozapine? Biol Psychiatry 1999; 45:1376–1383Google Scholar

16. Lindenmayer JP, Grochowski S, Mabugat L: Clozapine effects on positive and negative symptoms: a six-month trial in treatment-refractory schizophrenics. J Clin Psychopharmacol 1993; 14:201–204Google Scholar

17. Lieberman JA, Safferman AZ, Pollack S, Szymanski S, Johns C, Howard A, Kronig M, Bookstein P, Kane JM: Clinical effects of clozapine in chronic schizophrenia: response to treatment and predictors of outcome. Am J Psychiatry 1994; 151:1744–1752Google Scholar

18. Abraham G, Nair C, Tracy JI, Simpson GM, Josiassen RC: The effects of clozapine on symptom clusters in treatment-refractory patients. J Clin Psychopharmacol 1997; 17:49–53Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

19. VanderZwaag C, McGee M, McEvoy JP, Freudenreich O, Wilson WH, Cooper TB: Response of patients with treatment-refractory schizophrenia to clozapine within three serum level ranges. Am J Psychiatry 1996; 153:1579–1584Google Scholar

20. Hasegawa M, Gutierrez-Esteinou R, Way L, Meltzer HY: Relationship between clinical efficacy and clozapine concentrations in plasma in schizophrenia: effect of smoking. J Clin Psychopharmacol 1993; 13:383–390Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

21. Perry PJ, Miller DD, Arndt SV, Cadoret RJ: Clozapine and norclozapine plasma concentrations and clinical response of treatment-refractory schizophrenic patients. Am J Psychiatry 1991; 148:231–235; correction, 148:1427Google Scholar

22. Potkin SG, Bera R, Gulaskaram B, Costa J, Hayes S, Jin Y, Richmond G, Carreon D, Sitanggan K, Gerber B, Telfold J, Plon L, Plon H, Park L, Chang J-J, Oldroyd J, Cooper T: Plasma clozapine concentrations predict clinical response in treatment-resistant schizophrenia. J Clin Psychiatry 1994; 55(Sept suppl B):133–136Google Scholar

23. Kronig MH, Munne RA, Szymanski S, Safferman AZ, Pollack S, Cooper T, Kane JM, Lieberman JA: Plasma clozapine levels and clinical response for treatment-refractory schizophrenic patients. Am J Psychiatry 1995; 152:170–182Google Scholar