Cultural and Linguistic Barriers to Mental Health Service Access: The Deaf Consumer's Perspective

Abstract

OBJECTIVE: The authors investigated knowledge, attitudes, and beliefs about mental illness and providers held by a group of deaf adults. METHOD: The American Sign Language interviews of 54 deaf adults were analyzed. RESULTS: Recurrent themes included mistrust of providers, communication difficulty as a primary cause of mental health problems, profound concern with communication in therapy, and widespread ignorance about how to obtain services. CONCLUSIONS: Deaf consumers' views need due consideration in service delivery planning. Outreach regarding existing programs is essential. (Am J Psychiatry 1998; 155:982–984)

Mental health services for deaf persons have received increasing attention over the past decades (1, 2). However, relatively little research has focused on the perspectives of deaf consumers, even though approximately 22 million people in the United States have hearing losses (3). Hearing loss primarily affects language and communication. In fact, the median English literacy of deaf high school graduates is the equivalent of 4.5 grades (4). Since American Sign Language has its own unique vocabulary and grammar, practitioners with normal hearing and deaf individuals who use American Sign Language often lack a common language (1, 4, 5). In this study we sought an understanding of the deaf community's knowledge, attitudes, and beliefs about mental health and illness.

METHOD

Fifty-four deaf volunteers, 18 to 78 years old, from eastern Pennsylvania, New Jersey, and Delaware were interviewed in 1994 and 1995. Participants were recruited through live announcements at events in the deaf community and were selected on the basis of a communication preference for American Sign Language. After a complete description of the study was given to participants, written informed consent was obtained.

The difficulty and discomfort many deaf individuals have with written English ruled out using anonymous written surveys (1, 4, 5). Individual and group semistructured interviews were conducted in American Sign Language at homes, schools, churches, and community centers to eliminate the intimidating effect of institutional settings. The interview consisted of 89 questions covering demographic variables, family background, and knowledge, attitudes, and beliefs about mental health issues and services. Participant disclosure of personal experiences with mental health services was not required, so as to increase the participants' comfort during the interviews. Most questions were intentionally open ended to maximize disclosure. Follow-up questions were asked as necessary for clarification. The interviews were translated into written English.

Unlike the hypothesis-testing model of empirical research, this study used a hypothesis-generating approach. Folio VIEWS, a text-based, qualitative analysis software program, was used to identify and label recurrent themes, concepts, and processes that emerged across participant interviews (6). Excerpts relating to a similar theme, concept, or process from all interviews were extracted and studied for the discovery of patterns and development of theories, which will be empirically tested in subsequent research.

RESULTS

The study group comprised 23 men and 31 women. Most (82%) were Caucasian (N=44), 11% were African American (N=6), and 7% were Hispanic (N=4). All identified themselves as deaf (91%, N=49) or hard of hearing (9%, N=5). Onset of hearing loss was before the age of 6 years for 80% of the participants (N=43), between ages 6 and 18 for 9% (N=5), after age 18 for 4% (N=2), and unknown for 7% (N=4). Deaf adults with some postsecondary education were overrepresented in the study group—43% (N=23) versus 9% nationally (1)—which somewhat limits the generalization of the study's findings.

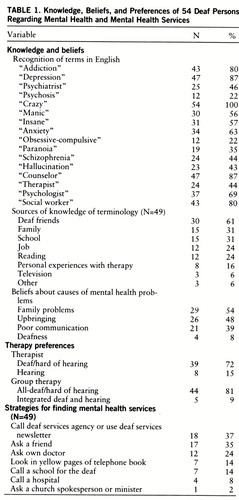

As shown in table 1, the participants' recognition of mental health terms in English varied widely; “addiction” was recognized by 80%, but “psychosis” was recognized by only 22%. Some could discuss concepts such as “depression” or “addiction” quite perceptively in American Sign Language but not in English. The participants had learned mental health terminology most frequently from deaf friends, family, school, work, and reading (table 1).

The participants overwhelmingly attributed mental health problems to external causes, such as family problems, one's upbringing, and poor communication (table 1). Few (9%, N=5) believed deafness itself caused mental health problems, but 41% (N=22) asserted that the communication problems, family stresses, and societal prejudice that accompany it could lead to problems ranging from suicidal depression to substance abuse and violent behavior.

The participants viewed both mental health institutions and practitioners as authoritarian, restrictive, and prejudiced. Some signed “mental hospital” by using PRISON, STRAIGHT-JACKET, or CRAZY-HOUSE (the capitalized words represent English glosses of the American Sign Language vocabulary used by participants). One woman shrugged, “From a deaf person's point of view, they [jail and mental hospital] are the same.” Another perception was that deaf clients were powerless and at the mercy of prejudiced, hearing authorities. The third recurring image was of a deaf person who is unable to communicate and is erroneously committed. One woman reported, “Even if I were just asking directions at the information desk [of a psychiatric hospital], miscommunication could lead to my being committed mistakenly. . . . I don't want to go there, even for a visit!”

The participants were split over whether their families would support their seeking therapy: 46% (N=25) believed their families would be supportive, and 46% (N=25) said it “depends.” The majority (93%, N=50), however, maintained that a friend would be supportive. The participants were divided about the disclosure of their use of mental health services to others beyond close friends; 54% (N=29) responded that they would disclose such information, whereas 46% (N=25) said they would keep it private. One observed, “The deaf community is like a family. One thing can spread to everyone, and all the world knows about it.” Others felt that disclosure could raise awareness and dispel stigma.

Sign language fluency was viewed as essential for mental health professionals. The participants felt that professionals accepted a minimal level of communication with deaf clients that would never be tolerated with hearing patients. Another contributing problem was that “many deaf people lack English skills. They are ashamed to write.” The participants appreciated and preferred therapy involving a qualified interpreter over uninterpreted therapy. However, some participants raised concerns about confidentiality and the interpreter's American Sign Language competency. The participants preferred a deaf therapist over a hearing therapist (table 1). “A deaf counselor knows the language, the culture; knows what deafness means . . . [and] is like me.” Others assumed that all mental health personnel would be hearing.

The participants were also asked about group therapy. They overwhelmingly preferred all-deaf/hard of hearing groups over integrated deaf and hearing groups (table 1), even with interpreting services. Typically, group discussions present major challenges to deaf members. Often, several people speak simultaneously or there are rapid exchanges, and the deaf member, being able to follow only one speaker at a time, misses much. Even skilled interpreters have difficulty keeping up.

More than one-half of the participants (56%, N=30) could not locate accessible mental health services. When prompted, participants stated they would seek referrals from a deaf service agency, friend, doctor, school for the deaf, or telephone book (table 1). More often, deaf participants relied on members of the deaf community who were respected for their sensitivity, common sense, and life experience to provide informal counseling, moral support, and even shelter.

DISCUSSION

That the participants so frequently cited communication difficulty as a primary cause of mental health problems points to its magnitude in the deaf experience. Attribution of mental health problems to communicative isolation or isolation during childhood further reinforces this point. To be effective, mental health professionals must not reenact this experience with deaf patients.

This study also demonstrates that deaf consumers are well aware of the contributions of interpreters and the advantages of direct communication with therapists. Providers who have little experience with interpreting need to recognize its limitations and learn how to work best with interpreters. Clinicians should never assume that the presence of an interpreter ensures adequate communication.

Mental health providers should be cognizant of their prevalent negative images within the deaf community. One cannot gain a client's cooperation without an awareness of culturally based fears that the client may bring to the interaction. It is important to keep in mind that, like other minority communities, the deaf community encompasses considerable diversity even though its members share many characteristics, preferences, and perspectives (7). Ignorance of existing resources constitutes another major barrier. Community outreach programs are clearly needed to familiarize both deaf consumers and providers with available resources. Clearly defined referral procedures for deaf patients, such as those suggested by Myers (2), would substantially improve resource utilization. Use of existing information pathways—the deaf community itself, deaf services agencies, and deaf schools—for new outreach efforts is recommended. However, without the active support of both the psychiatric and deaf communities, services will be underutilized.

A final challenge for providers and administrators is to determine how these viewpoints can be incorporated into improved service delivery systems. Strategies for cost-effective, accessible health services for individuals with special needs, such as deaf individuals, have yet to be investigated and reported. To our knowledge, the impact of gatekeeping and managed care on the deaf community has not been examined to date.

|

Received June 19, 1997; revisions received Nov. 10, 1997, and Jan. 30, 1998; accepted Feb. 26, 1998. From the Deafness and Family Communication Center, Department of Psychiatry at the Child Guidance Center of Children's Hospital of Philadelphia and Department of Pediatrics at the Children's Seashore House, University of Pennsylvania School of Medicine, Philadelphia. Address reprint requests to Dr. Steinberg, Children's Seashore House, 3405 Civic Center Blvd., Philadelphia, PA 19104-4388; [email protected] (e-mail). Supported by a Picker/Commonwealth Scholars Award to Dr. Steinberg. The authors thank David Hufford, Ph.D., for support and assistance with the project.

1 Steinberg A: Issues in providing mental health services to hearing-impaired persons. Hosp Community Psychiatry 1991; 142:380–389Google Scholar

2 Myers RR (ed): Standards of Care for the Delivery of Mental Health Services to Deaf and Hard of Hearing Persons. Silver Spring, Md, National Association of the Deaf, 1995Google Scholar

3 National Center for Health Statistics: National Health Interview Survey, Series 10, Number 188. Washington, DC, US Government Printing Office, 1994, tables 1 and 7Google Scholar

4 Holt JA: Stanford Achievement Test, 8th ed: reading comprehension subgroup results. Am Ann Deaf 1994; 138:172–175Crossref, Google Scholar

5 Ebert DA, Heckerling PS: Communication with deaf patients: knowledge, beliefs, and practices of physicians. JAMA 1995; 273:227–229Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

6 Folio VIEWS Infobase Production Kit. Provo, Utah, Folio Corp, 1995Google Scholar

7 Steinberg AG, Sullivan VJ, Loew RC: Cultural and linguistic barriers to mental health service access: the deaf consumer's perspective, in Mental Health Interventions and the Deaf Community. Edited by Leigh IW. Washington, DC, Gallaudet University Press (in press)Google Scholar