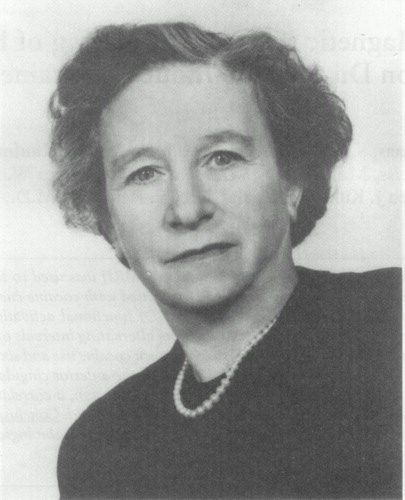

Frieda Fromm-Reichmann, 1889–1957

Frieda Fromm-Reichmann was a major pioneer in using the therapeutic relationship to treat individuals afflicted with severe mental illness. Working at Chestnut Lodge Hospital in Rockville, Md., she drew from classical Freudian psychoanalysis and Sullivanian interpersonal analysis to create an integrated approach applicable to patients with schizophrenia and bipolar disorder. The amalgamation is detailed in her Principles of Intensive Psychotherapy (1), which constitutes the foundation of psychodynamic psychotherapy, the most common form of psychosocial treatment practiced in the world today for all varieties of mental and emotional disorders, both psychotic and nonpsychotic.

Born in 1889 in Karlsruhe, Germany, of a middle-class German Jewish family, Frieda was the oldest of three daughters. Ahead of her time even as a young woman, she pursued medicine and graduated from medical school in 1914. She studied neurology, war-related brain injuries, and dementia praecox before pursuing psychoanalytic training and practice in Berlin, Heidelberg, and southwestern Germany. With the rise of Hitler, Frieda emigrated to the United States; in 1935 she joined the staff of Chestnut Lodge Hospital, where she remained until her death in 1957.

Frieda considered herself primarily a psychoanalyst because she used the concepts of transference and resistance, the unconscious, and the importance of early childhood experiences for personality development. Nevertheless, she introduced modifications to the classical model that were considered iconoclastic at the time. These included treating patients face to face with and without the couch, insisting that patients with schizophrenia can form transferences, focusing on the here and now of the therapeutic situation in addition to using it as a vehicle reflecting the patient's past relationships, stressing the impact of countertransferences and the therapist's values on the therapeutic work, seeking beyond (and before) the oedipal period of development for the sources of psychotic conflict, de-emphasizing classical libido and structural theory in favor of interpersonal, object relations theory, and attempting to help psychotic patients integrate rather than reject their disorder (the precursor of psychoeducation).

She was uniformly described as short in stature (at 4 feet, 10 inches) and tall in creativity, intellect, and character. Her many teachers, colleagues, students, patients, and analysands have attested to her extraordinary capacity to listen and empathize. She was always open and interested in exchanging ideas, and while forthright in her views she could alter them in response to new observations or to better theoretical framings of those observations. Over the course of her work at Chestnut Lodge, for example, Frieda moved from an initial position of seeing the patient as a victim of negative early experiences to a more balanced view that factored in the patient's contribution and responsibility. Ultimately, she regarded our patients as our teachers.

Address reprint requests to Dr. McGlashan, Yale Psychiatric Institute, 184 Liberty St., New Haven, CT 06519. Photograph courtesy of Dr. Fenton, Chestnut Lodge Research Institute.

1. Fromm-Reichmann F: Principles of Intensive Psychotherapy. Chicago, Chicago University Press, 1950Google Scholar