Posttraumatic Stress Disorder in a Community Group of Former Prisoners of War: A Normative Response to Severe Trauma

Abstract

OBJECTIVE: The goal of this study was to assess and describe the long-term impact of traumatic prisoner of war (POW) experiences within the context of posttraumatic psychopathology. Specifically, the authors attempted to investigate the relative degree of normative response represented by posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) in comparison to other DSM axis I disorders often found to be present, either alone or concomitant with other disorders, in survivors of trauma. METHOD: A community group of 262 U.S. World War II and Korean War former POWs was recruited. These men had been exposed to the multiple traumas of combat, capture, and imprisonment, yet few had ever sought mental health treatment. They were assessed for psychopathology with diagnostic interviews and psychodiagnostic testing. Regression analyses were used to assess the contributions of age at capture, war trauma, and postwar social support to PTSD and the other diagnosed disorders. RESULTS: More than half of the men (53%) met criteria for lifetime PTSD, and 29% met criteria for current PTSD. The most severely traumatized group (POWs held by the Japanese) had PTSD lifetime rates of 84% and current rates of 59%. Fifty-five percent of those with current PTSD were free from the other current axis I disorders (uncomplicated PTSD). In addition, 34% of those with lifetime PTSD had PTSD as their only lifetime axis I diagnosis. Regression analyses indicated that age at capture, severity of exposure to trauma, and postmilitary social support were moderately predictive of PTSD and only weakly predictive of other disorders. CONCLUSIONS: These findings indicate that PTSD is a persistent, normative, and primary consequence of exposure to severe trauma. (Am J Psychiatry 1997; 154:1576–1581)

Many studies indicate that a majority of individuals exposed to severe trauma, such as former prisoners of war (POWs) (1–3), torture victims (4), and survivors of war in the former Yugoslavia (5), develop posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD). In a group of American POWs, a lifetime PTSD rate of 67% was found (1). Among schoolchildren exposed to a sniper attack, 58% met criteria for PTSD (6). The National Vietnam Veterans Readjustment Study (7) found high lifetime PTSD rates among veterans wounded in combat (67%). PTSD rates of 59% to 66% were reported among crime victims exposed to life threat combined with injury (8). The National Comorbidity Study (9) found lifetime PTSD rates among those exposed to severe trauma ranging from 39% for combat to 65% for rape. Studies in which exposure to trauma has been less severe, however, suggest that most subjects exposed to trauma did not develop PTSD (10–12). It further has been proposed that PTSD may represent an abnormal, rather than a normal, response to trauma (13, 14).

Exposure to trauma alone does not always lead to PTSD, and severity of trauma does not fully predict the likelihood of development of PTSD. Other contributing factors have been identified, including prior exposure to trauma (15), a history of childhood conduct problems (7), pretrauma personality (16), heritability (17), age at exposure to trauma (18, 19), and posttraumatic factors such as social support (20) and exposure to reactivating stressors (21). Green et al. (22) examined the contribution of premilitary, military, and postmilitary risk factors to PTSD and other postwar diagnoses in a sample of Vietnam veterans. Although pre- and postmilitary factors were contributory, PTSD was related primarily to war trauma. Panic disorder also was highly related to war trauma. Prewar functioning played a stronger role in several non-PTSD diagnoses.

Although risk factors other than trauma may affect posttraumatic psychiatric status when trauma is less severe or limited to a single exposure, these other risk factors may decrease in significance as the severity of and duration of exposure to trauma increase (23). Foy et al. (24) found that while Vietnam veterans with PTSD generally had the highest rates of family psychopathology, the contribution of family history was not significant for those with high levels of combat exposure; regardless of family history of mental illness, veterans with high levels of combat exposure developed high rates of PTSD. In a sample of POWs, family history of mental illness, premilitary adjustment problems, and severe childhood trauma did not predict development of PTSD (18).

Besides lack of control for severity of trauma, variance in assessment methods has affected the results of studies assessing PTSD. The National Institute of Mental Health Diagnostic Interview Schedule (DIS) (25), based on DSM-III criteria, often was used despite the low sensitivity of early versions to the presence of PTSD (26), particularly when they were administered by nonclinicians (7). For example, the DIS was used in community prevalence studies and yielded lifetime rates of 1.0% (10) and 1.3% (27). Three recent studies using DSM-III-R criteria reported significantly higher rates of PTSD. Structured interviews using a DSM-III-R version of the DIS found histories of PTSD in 12.3% of a sample of U.S. women (28) and among 11.3% of women and 6% of men enrolled in an urban health maintenance organization (11). Although the Composite International Diagnostic Interview (29) underdiagnoses PTSD (9), in the National Comorbidity Study it yielded a lifetime PTSD rate of 7.8% in the general population.

Rates of other disorders, most commonly other anxiety disorders, depression, and alcohol abuse, are elevated among those exposed to trauma (9, 30, 31). This comorbidity pattern resembles that found with other anxiety syndromes (32). Studies assessing both current and lifetime diagnoses, however, suggest that with time, co-occurring disorders fade while PTSD persists (7, 33, 34). In the National Vietnam Veterans Readjustment Study (7), the comorbidity of PTSD with a group of other common DIS-detected psychiatric disorders declined from approximately 99% lifetime to approximately 50% at the time of interview.

Particularly in community surveys of those exposed to severe trauma, PTSD has been shown to be central, common, and persistent, consistent with a view of PTSD as a normative response. With this in mind, we present data describing psychiatric disorders and their correlates in a community group of persons with histories of exposure to severe trauma.

METHOD

The subjects were community-residing former POWs who completed diagnostic interviews and psychodiagnostic testing at the Veterans Affairs (VA) Medical Center in Minneapolis. All were men and resided in Minnesota, Wisconsin, or North Dakota. Two were Native American, one was Hispanic, and the rest were white. Their median age was 71, and their median education was 12 years. They were recruited through direct mailings to POWs known to be residing in the area. Approximately two-thirds were receiving at least some of their health care from a VA medical center, and 7% were involved in mental health care at the time of recruitment. Follow-up telephone contacts with 344 potential subjects resulted in 262 completed assessments (76%) between August 1991 and August 1994. Forty-four (13%) were willing to participate but could not be scheduled because of ill health or distance from the VA Medical Center in Minneapolis; 38 (11%) declined to participate. Fifty-six of the POWs were held by Japan, 191 by Germany, and 15 by North Korea. After a complete description of the study to the subjects, written informed consent was obtained.

All subjects were administered the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-III-R Non-Patient Version Modified for the Vietnam Veterans Readjustment Study (SCID PTSD) (35) and the SCID Non-Patient Edition (36). Psychological testing assisted the diagnostic process; results are reported elsewhere (37). All four interviewers were experienced in psychodiagnosis and the assessment of combat-related PTSD. Eight interviews were directly observed by a second rater, and five interviews were taped and independently reviewed by two additional raters, allowing three pairs of observations for these cases. There were no disagreements as to the presence or absence of current or lifetime PTSD among these 23 possible pairs of ratings. In addition, there were no disagreements as to the presence or absence of the other most common current or lifetime axis I diagnoses among 130 possible pairs of ratings. Combat exposure was self-reported on the Combat Exposure Scale (38). Social support was indexed through the sum of responses to items from the Social Reintegration Scale (39). Data on demographic variables were obtained through use of a standard POW background questionnaire (40). Information from physical examinations performed shortly after repatriation was reviewed for a random sample of 36 POWs, and their current reports of age at capture, weight loss, and injuries in captivity were corroborated.

RESULTS

Exposure to Trauma and Prevalence of Disorders

Sixty-three percent of our group sustained wounds or injuries in the course of their combat and captivity. Duration of individual combat involvement ranged from 1 to 31 months (mean=4, SD=4). The subjects had a mean Combat Exposure Scale score of 21.5 (SD=7.2), placing the group in the moderate range of combat exposure (41). Their length of captivity ranged from 1 to 46 months (mean=16, SD=14). They experienced an average weight loss during captivity of 27.7% (SD=12.1%).

DSM-IV redefined PTSD criterion A (the stressor criterion), requiring that intense fear, helplessness, or horror be experienced during exposure to trauma. We reviewed DSM-III-R criterion A information and found that all subjects met DSM-IV criterion A. In addition, DSM-IV adds a criterion F, requiring that the PTSD symptoms cause clinically significant distress or impairment. One subject with current DSM-III-R PTSD did not appear distressed or impaired by his symptoms. His Global Assessment of Function Scale score was 85. The remaining subjects with current PTSD had a mean Global Assessment of Function Scale score of 65.7 (SD=9.1), suggesting mild symptoms. It is important to note, however, that these veterans demonstrated an ability to function under the most extreme circumstances, and many reported that an important survival skill was the suppression of their emotional reactions. Their primary sources of distress were indelible and intrusive memories, anxiety, and hyperarousal, rather than the social and occupational impairments that contribute heavily to the assignment of Global Assessment of Function Scale ratings.

DSM-IV also moves one symptom, physiological reactivity on exposure to cues, from criterion group D (increased arousal) to group B (reexperiencing the trauma). Rescored SCID data reclassified six subjects from lifetime DSM-III-R PTSD to absence of lifetime DSM-IV PTSD and three subjects from current DSM-III-R PTSD to absence of current DSM-IV PTSD. DSM-III-R results are reported below.

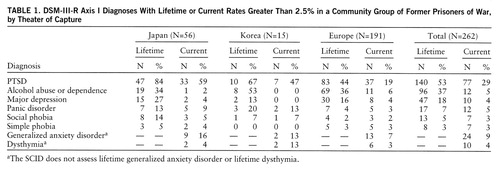

The mean number of lifetime axis I disorders per person was 2.3 (SD=1.3, range=0–7). PTSD was the most prevalent disorder: 53% (N=140) met lifetime criteria, and 29% (N=77) met current criteria (table 1). These findings are comparable to the National Vietnam Veterans Readjustment Study findings noted earlier (7). The lifetime rate of 37% for alcohol abuse or dependence is somewhat higher than the lifetime rate of 33% noted in the National Comorbidity Study (42) for males in the general population. As a group, POWs held by Germany had a lower degree of exposure to trauma than those held by Japan or Korea, with corresponding differences in rates of certain disorders. Two multivariate analyses of variance examined the interaction of diagnoses with theater of capture: for lifetime diagnoses, PTSD (F=16.0, df=2,260, p<0.0001), panic disorder (F=5.1, df=2,260, p<0.01), and social phobia (F=7.2, df=2,260, p<0.001) varied significantly by theater of capture. For current diagnoses, PTSD (F=19.9, df=2,260, p<0.0001) and panic disorder (F=5.0, df=2,260, p<0.01) varied significantly by theater of capture. Higher rates of these disorders for POWs held by Japan or Korea are observed in table 1.

Only 9.5% of the total group were free of all current PTSD symptoms. Eighty-two percent of subjects without current PTSD also were free of the other 33 current axis I disorders assessed by the SCID. Fifty-five percent of those with current PTSD were free of the other current axis I disorders; they had uncomplicated PTSD. In addition, 34% of those with lifetime PTSD had PTSD as their only lifetime axis I diagnosis.

Multivariate Prediction of PTSD and Other Axis I Disorders

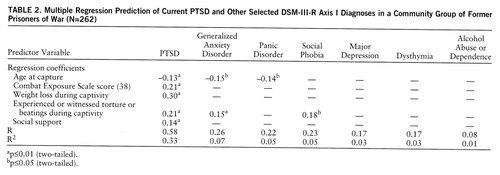

Table 2 summarizes multiple regression equations that used age at time of capture, indicators of exposure to trauma, and the social support index to predict current PTSD and the other most frequent current axis I disorders. Preliminary analyses showed that many theoretically relevant variables were not significantly correlated with axis I diagnoses and were statistically infrequent. For example, fewer than 2% admitted to treatment for a mental problem before service or to a family history of mental problems. Statistical transformations of these skewed variables did not yield significant correlations with axis I diagnoses; therefore, they were not included in table 2 analyses.

The five variables shown in table 2 were the only significant predictors of axis I diagnostic status, and together they accounted for 33% of the variance in PTSD status. Age at capture was negatively related to PTSD: being older during exposure to trauma was a protective factor against later PTSD. Table 2 also shows the much lower power of these variables to predict other axis I disorders. Only two of the variables were significant predictors of other disorders: age at capture (generalized anxiety and panic disorders) and the experience of torture or beatings (generalized anxiety disorder and social phobia). None of the prediction equations accounted for more than 7% of the variance in the other disorders. Parallel analyses (not shown) for the lifetime diagnoses yielded highly similar results, with the predictors accounting for 33% of the variance in lifetime PTSD status and no more than 7% of the variance in any of the other lifetime axis I disorders. Separate discriminant analyses (not shown) based on the predictor variables in table 2 yielded highly significant functions that correctly classified 77% of the lifetime PTSD cases and 80% of the current PTSD cases, through use of a jackknifed classification procedure. Parallel discriminant analyses attempting to predict the comorbid disorders were nonsignificant.

If response to trauma were nonspecific, a greater scattering of significant regression weights would be observed across table 2, as would a more robust ability to predict status of disorders other than PTSD. Table 2 shows, however, a concentration of predictive power under the disorder of PTSD, suggesting that response to trauma is better represented by PTSD than by the other disorders.

DISCUSSION

In accord with many previous reports, our findings indicate that PTSD is both a frequent and central consequence of exposure to severe trauma and is the diagnostic construct that best represents primary responses to trauma exposure. Consistent with other findings, we found lifetime PTSD in over half (53%) of our subjects; a substantial minority (29%) still met PTSD criteria 40–50 years after trauma exposure. In other words, only 45% of those with lifetime PTSD experienced symptom reduction sufficient to fall below current PTSD criteria. These findings also suggest that PTSD without comorbid axis I diagnoses may be more common in certain trauma-exposed groups than previous studies suggest.

Community surveys of individuals exposed to severe trauma (6–9) can lead to quite different conclusions than those suggested by studies of clinical samples. In the present study, few subjects had ever received mental health services, and all subjects were both exposed to combat and subjected to the hardships of capture and captivity. Their trauma exposure was comparable on common dimensions, and average levels of trauma exposure were high. To illustrate, we present histories of two veterans who had not sought mental health treatment and who met criteria for current and lifetime PTSD and no other axis I disorders.

Case 1. A 73-year-old white man reported a normal childhood; he left school after 11th grade to work full time. Although married, he was drafted at age 24, trained as a medic, and sent to north Africa in 1943. He provided acute care for combat-wounded Americans, including close friends, many of whom he could not save. He regrets following orders to not engage in combat; from a secure vantage point he helplessly watched a German machine gunner kill and wound Americans. He wishes that he had removed his Red Cross band and shot the machine gunner. During his 30 months as a POW he experienced multiple traumatic events including being captured; being flown to Italy on a plane that was attacked and landed with one engine on fire at an airfield under Allied attack; witnessing the mistreatment, segregation, and eventual disappearance of American Jewish POWs (“They were herded off, never to be seen again”); unsuccessfully trying to stop the execution of a fellow POW by his comrades; and removing dead civilians including children from destroyed bomb shelters.

Upon repatriation, he met his 2½-year-old son for the first time. He and his wife raised four children. Because his return to work at a brewery was unsatisfactory, he attended college for 2 years. He attempted to sell real estate for about a year, eventually returning to his original employer. He reported that before the war, he was “interested in everything” however, upon his return he was interested in very little. He now is “very choosy about activities and interests,” and his social contacts are limited to his family. He has had peptic ulcer disease and chronic arthralgias of his knees since World War II. His chief psychiatric complaints include intrusive recollections, difficulties falling asleep and staying asleep since the war (he averages only 4 hours of sleep per night), and feeling distant from and mistrustful of people outside his family. He has no close friendships and does not associate with other veterans. Any portrayal of disasters or injuries (e.g., coverage of the Gulf War and its bombings) provokes nightmares of his POW experiences. He never sought help for these problems and declined our offer of mental health treatment. His only axis I disorder was PTSD, lifetime and current.

Case 2. A 74-year-old white man reported a normal childhood; he left school after 10th grade to work and play semiprofessional baseball. His National Guard unit was activated in 1941 and sent to the Philippines. Japan attacked on Dec. 8, 1941. Following fierce combat with heavy casualties, mainland Allied forces surrendered April 9, 1942. Together with over 10,000 ill and underfed Americans, he was forced onto the Bataan Death March. As a POW, he witnessed senseless executions and endured beatings, death threats, malnutrition, and multiple untreated medical diseases (43). While he labored, his weight dropped from 155 to 80 pounds until he was too ill to work. In December 1944 he and 1,600 other POWs were forced into the hold of one of the last ships to leave the Philippines. Only half survived transport to Japan. The unmarked ship was sunk by American planes after leaving port; he swam to shore. He was recaptured and put on another ship that was hit by American planes near Formosa (Taiwan); he again swam to shore. The journey to Japan included 49 days of confinement in the overcrowded, intensely hot holds of three different ships with little food, water, or sanitation (44). Many POWs became delirious, attacked fellow POWs, and were killed. In Japan he labored in a coal mine for 12 hours per day, 10 days at a time, followed by 1 day off. Rations were about 1,000 calories per day. Anyone too ill to work was placed on half-rations. Camp officials were under orders to execute all POWs if America invaded Japan; instead, they abandoned the camp following the bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki and the Japanese surrender. Throughout his captivity and postwar life he has maintained an inner posture of resistance. He returned home, married, recuperated from tuberculosis, and began work for the Postal Service, where he remained a clerk for 36 years, failing to be promoted “because of my personality.” He and his wife raised three children.

His only axis I disorder was PTSD, lifetime and current. He complained of nervousness to several nonpsychiatrist physicians after World War II but was not referred for mental health services; he recalled being told that he would “have to live with it.” His records indicate that he refused tranquilizers. Since participation in the present study, he joined a POW support group that meets twice monthly. He appears anxious and speaks rapidly. He suffers a trauma-related phobia of closed spaces and from most of the PTSD symptoms, chiefly daily intrusive recollections, frequent nightmares, hypervigilance, and survivor guilt. His only social contacts are a few other POWs of Japan and his children.

Cases such as these appear in community samples and offer insights into chronic untreated psychiatric disorders such as PTSD. Generalizations about the effects of trauma are potentially misleading when drawn from studies of clinical populations that offer insights more specific to treatment-seeking samples. In such samples individuals with concomitant PTSD and other axis I disorders may be overrepresented, and factors other than trauma may have contributed to the observed psychopathology. See King and King's report (45) for a discussion of other validity issues in PTSD research.

Being older at the time of exposure to trauma appeared to reduce the risk for later PTSD symptoms; however, understanding of other protective factors is currently minimal. Research has emphasized vulnerability factors in the search for PTSD's causal bases. More emphasis on protective factors (46) is needed. Shifting more attention to those who experience few negative effects from exposure to trauma also might improve our understanding of recovery mechanisms and contribute to more effective treatment (47).

Our findings that 53% of all the POWs, including 84% of those held by Japan, met criteria for lifetime PTSD are consistent with other reports (1, 2) and indicate the persistence of trauma-related psychopathology in significant proportions of persons exposed to severe trauma. In this, as in a substantial number of other studies including many cited earlier, exposure to trauma was the strongest risk factor for the development of PTSD. Severity of exposure to trauma is clearly predictive of PTSD and less predictive of the other disorders commonly observed in trauma survivors. It has been suggested that the longer PTSD lasts, the less important the role of exposure to trauma becomes in explaining posttraumatic symptoms (48). Our data suggest otherwise: 45–50 years later, exposure to trauma remained the strongest predictor of PTSD symptoms. Our findings indicate that in the context of severe trauma, PTSD is a persistent, normative, and primary response.

|

|

Presented in part at the International Society for Traumatic Stress Studies Convention, Boston, Nov. 2–6, 1995. Received Sept. 16, 1996; revisions received Jan. 24 and May 7, 1997; accepted June 6, 1997. From the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs Medical Center, Minneapolis; and Department of Psychology, Institute of Child Development, and Department of Psychiatry, University of Minnesota, Minneapolis. Address reprint requests to Dr. Engdahl, Psychology Service (116B), VA Medical Center, One Veterans Dr., Minneapolis, MN 55417; [email protected] (e-mail). Supported by research funds from the Department of Veterans Affairs and by the Department of Veterans Affairs Medical Center, Minneapolis. The authors thank the prisoner of war volunteers, Julee Blake, Daniel Sandstrom, and Nicholas Michel for their assistance in this project.

1. Kluznik JC, Speed N, VanValkenburg C, McGraw R: Forty-year follow-up of United States prisoners of war. Am J Psychiatry 1986; 143:1443–1446Google Scholar

2. Goldstein G, van Kammen W, Shelly C, Miller DJ, van Kammen DP: Survivors of imprisonment in the Pacific theater during World War II. Am J Psychiatry 1987; 144:1210–1213Google Scholar

3. Eberly RE, Engdahl BE: Prevalence of somatic and psychiatric disorders among former POWs. Hosp Community Psychiatry 1991; 42:807–813Abstract, Google Scholar

4. Ramsay R, Gorst-Unsworth C, Turner S: Psychiatric morbidity in survivors of organised state violence including torture: a retrospective series. Br J Psychiatry 1993; 162:55–59Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

5. Weine SM, Becker DF, McGlashan TH, Laub D, Lazrove S, Vojvoda D, Hyman L: Psychiatric consequences of “ethnic cleansing”: clinical assessments and trauma testimonies of newly resettled Bosnian refugees. Am J Psychiatry 1995; 152:536–542Link, Google Scholar

6. Pynoos RS, Frederick C, Nader K, Arroyo W, Steinberg A, Eth S, Nunez F, Fairbanks L: Life-threat and posttraumatic stress in school-age children. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1987; 45:1057–1063Google Scholar

7. Kulka RA, Schlenger WE, Fairbank JA, Hough RL, Jordan BK, Marmar CR, Weiss DS: Trauma and the Vietnam War Generation: Report of Findings From the National Vietnam Veterans Readjustment Study. New York, Brunner/Mazel, 1990Google Scholar

8. Kilpatrick DG, Resnick HS: PTSD associated with exposure to criminal victimization in clinical and community populations, in Posttraumatic Stress Disorder: DSM-IV and Beyond. Edited by Davidson JRT, Foa EB. Washington DC, American Psychiatric Press, 1993, pp 113–146Google Scholar

9. Kessler RC, Sonnega A, Bromet E, Hughes M, Nelson CB: Posttraumatic stress disorder in the National Comorbidity Survey. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1995; 52:1048–1060Google Scholar

10. Helzer JE, Robins LN, McEvoy L: Post-traumatic stress disorder in the general population. N Engl J Med 1987; 317:1630–1634Google Scholar

11. Breslau N, Davis GC, Andreski P, Peterson E: Traumatic events and posttraumatic stress disorder in an urban population of young adults. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1991; 48:216–222Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

12. Southwick SM, Morgan A, Nagy LM, Bremner D, Nicholaou AL, Johnson DR, Rosenheck R, Charney DS: Trauma-related symptoms in veterans of Operation Desert Storm: a preliminary report. Am J Psychiatry 1993; 150:1524–1538Google Scholar

13. Worthington ER: Demographic and pre-service variables as predictors of post-military service adjustment, in Stress Disorders Among Vietnam Veterans: Theory, Research, and Treatment. Edited by Figley CR. New York, Brunner/Mazel, 1978, pp 173–187Google Scholar

14. Yehuda R, McFarlane AC: Conflict between current knowledge about posttraumatic stress disorder and its original conceptual basis. Am J Psychiatry 1995; 152:1705–1713Google Scholar

15. Bremner JD, Southwick SM, Johnson DR, Yehuda R, Charney DS: Childhood physical abuse and combat-related posttraumatic stress disorder in Vietnam veterans. Am J Psychiatry 1993; 150:235–239Link, Google Scholar

16. Schnurr PP, Friedman MJ, Rosenberg SD: Premilitary MMPI scores as predictors of combat-related PTSD symptoms. Am J Psychiatry 1993; 150:479–483Link, Google Scholar

17. True WR, Rice J, Eisen SA, Heath AC, Goldberg J, Lyons MJ, Nowak J: A twin study of genetic and environmental contributions to liability for posttraumatic stress symptoms. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1993; 50:257–264Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

18. Speed N, Engdahl BE, Schwartz J, Eberly RE: Posttraumatic stress disorder as a consequence of the POW experience. J Nerv Ment Dis 1989; 177:147–153Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

19. King DW, King LA, Foy DW, Gudanowski DM: Prewar factors in combat-related posttraumatic stress disorder: structural equation modeling with a national sample of female and male Vietnam veterans. J Consult Clin Psychol 1996; 64:520–531Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

20. Keane TM, Scott WO, Chavoya GA, Lamparski DM, Fairbank JA: Social support in Vietnam veterans with posttraumatic stress disorder: a comparative analysis. J Consult Clin Psychol 1985; 53:95–102Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

21. Solomon Z: Combat Stress Reaction: The Enduring Toll of War. New York, Plenum, 1993Google Scholar

22. Green BL, Grace MC, Lindy JD, Gleser GC, Leonard A: Risk factors for PTSD and other diagnoses in a general sample of Vietnam veterans. Am J Psychiatry 1990; 147:729–733Link, Google Scholar

23. March JS: The nosology of posttraumatic stress disorder. J Anxiety Disord 1990; 4:61–82Crossref, Google Scholar

24. Foy DW, Resnick HS, Sipprelle RC, Carroll EM: Premilitary, military, and postmilitary factors in the development of combat-related posttraumatic stress disorder. Behavior Therapist 1987; 10:3–9Google Scholar

25. Robins LN, Helzer JE, Croughan JL (eds): National Institute of Mental Health Diagnostic Interview Schedule, version III: PHS Publication ADM-T-42-3. Rockville, Md, NIMH, 1981Google Scholar

26. McFarlane AC, Papay P: Multiple diagnoses in posttraumatic stress disorder in the victims of natural disaster. J Nerv Ment Dis 1992; 180:498–504Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

27. Davidson RT, Hughes D, Blazer D, George LK: Posttraumatic stress disorder in the community: an epidemiological study. Psychol Med 1991; 21:1–19Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

28. Resnick HS, Kilpatrick DG, Dansky BS, Saunders BE, Best CL: Prevalence of civilian trauma and posttraumatic stress disorder in a representative national sample of women. J Consult Clin Psychol 1993; 61:984–991Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

29. World Health Organization: Composite International Diagnostic Interview (CIDI), version 1.0. Geneva, WHO, 1990Google Scholar

30. Brett EA: Classification of PTSD in DSM IV: anxiety disorder, dissociative disorder, or stress disorder, in Posttraumatic Stress Disorder: DSM-IV and Beyond. Edited by Davidson RT, Foa EB. Washington DC, American Psychiatric Press, 1993, pp 191–204Google Scholar

31. Rundell JR, Ursano RJ, Holloway HC, Silberman EK: Psychiatric responses to trauma. Hosp Community Psychiatry 1989; 40:68–74Abstract, Google Scholar

32. de Ruiter C, Rijkekn H, Garssen B, van Schaik A, Kraaimaat F: Comorbidity among the anxiety disorders. J Anxiety Disord 1989; 3:57–68Crossref, Google Scholar

33. Blank AS Jr: The longitudinal course of posttraumatic stress disorder, in Posttraumatic Stress Disorder: DSM-IV and Beyond. Edited by Davidson RT, Foa EB. Washington DC, American Psychiatric Press, 1993, pp 3–22Google Scholar

34. Page WF, Engdahl BE, Eberly RE: The persistence of PTSD in former POWs, in PTSD: Acute and Long-Term Responses to Trauma. Edited by Fullerton C, Ursano R. Washington, DC, American Psychiatric Press, 1997, pp 147–158Google Scholar

35. Spitzer RL, Williams JB: Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-III-R—Non-Patient Version Modified for the Vietnam Veterans Readjustment Study. New York, New York State Psychiatric Institute, Biometrics Research, April 1, 1987Google Scholar

36. Spitzer RL, Williams JBW, Gibbon M, First MB: Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-III-R—Non-Patient Edition (SCID-NP, Version 1.0). Washington, DC, American Psychiatric Press, 1990Google Scholar

37. Engdahl BE, Eberly RE, Blake JD: The assessment of posttraumatic stress disorder in World War II veterans. Psychol Assess 1996; 8:445–449Crossref, Google Scholar

38. Keane TM, Fairbank JA, Caddell JM, Zimmerling RT, Taylor KL, Moira CA: Clinical evaluation of a measure to assess combat exposure. Psychol Assess 1989; 1:53–55Crossref, Google Scholar

39. Laufer RS, Yaeger T, Frey-Wouters E, Donellan J: Post-war trauma: social and psychological problems of Vietnam veterans and their peers, in Legacies of Vietnam, vol III. Washington, DC, Veterans Administration, US Government Printing Office, 1981Google Scholar

40. Veterans Administration: Former POW Medical History: VA Form 10-0048. Washington, DC, US Government Printing Office, 1984Google Scholar

41. Spiro A, Schnurr PP, Aldwin CA: Prevalence of combat-related PTSD in older men. Psychol Aging 1994; 9:17–26Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

42. Kessler RC, Crum RM, Warner LA, Nelson CB, Schulenberg J, Anthony JC: Lifetime co-occurrence of DSM-III-R alcohol abuse and dependence with other psychiatric disorders in the National Comorbidity Survey. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1997; 54:313–321Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

43. Dawes G: Prisoners of the Japanese. New York, Morrow, 1993Google Scholar

44. Jones BB: The December Ship: A Story of Lt Col Arden R Boellner's Capture in the Philippines, Imprisonment, and Death in a World War II Japanese Hellship. Jefferson, NC, McFarland & Co, 1992Google Scholar

45. King DW, King LA: Validity issues in research on Vietnam veteran adjustment. Psychol Bull 1991; 109:107–124Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

46. Hendin H, Haas AP: Combat adaptations of Vietnam veterans without posttraumatic stress disorders. Am J Psychiatry 1984; 141:956–960Link, Google Scholar

47. Basic Behavioral Science Task Force: Basic behavioral science research for mental health: vulnerability and resilience. Am Psychol 1996; 51:22–28Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

48. McFarlane AC, Yehuda R: Resilience, vulnerability, and the course of posttraumatic reactions, in Traumatic Stress: The Effects of Overwhelming Experience on Mind, Body, and Society. Edited by van der Kolk BA, McFarlane AC, Weisaeth L. New York, Guilford Press, 1996, pp 155–181Google Scholar