Assessment of Testamentary Capacity and Vulnerability to Undue Influence

Mr. A, an 84-year-old man with no past psychiatric history, made a will leaving his estate to his stepdaughter in 1991, at which time he and his wife had been estranged from his stepson for many years. In the next few years, Mr. A gave financial gifts to his stepdaughter that allowed her to purchase houses that he and his wife shared with her, and he continued to live with her after his wife died in 1994. Mr. A was diagnosed with rectal cancer in 1994 and refused treatment. In 1995, he became incontinent and had difficulty caring for himself. His stepdaughter sought help from a home care program, and a worker came to assist Mr. A with a bath. Mr. A complained about the care he received, saying that he had been assaulted by being given a bath “with a hose.” He became suspicious of his stepdaughter’s motives. He also became increasingly upset when his stepdaughter went out to work as a seamstress, accusing her of being a prostitute. Mr. A contacted a friend of his stepson and complained of his situation. The stepson came to the town where Mr. A lived to investigate. He found Mr. A on the street several blocks from his home carrying a large sum of money. He immediately took Mr. A to a lawyer, and within 2 days a new will had been drafted that left Mr. A’s estate to the stepson. Mr. A moved in with his stepson. When seen a year later by a psychiatrist, Mr. A was diagnosed as having mild to moderate Alzheimer’s disease. He continued to live with his stepson until he died in 1997. His stepdaughter subsequently challenged the 1995 will. Did Mr. A have the capacity to draft a new will in 1995, and was he unduly influenced by his stepson? What are the legal, medical, and psychiatric issues that a psychiatrist should be aware of if called upon to assist in making these determinations at the time of the drafting of the will or retrospectively, when the will is being challenged? (Adapted from reference 1 .)

Testamentary capacity is a construct rooted in both the legal and medical domains, thus inviting a collaborative approach to its definition and assessment. Challenges to testamentary capacity are made on a legal basis, and the judge remains the final arbiter. However, the evidence to support a challenge may be informed by the assessment of a medical expert (2) .

We can expect challenges to testamentary capacity to increase during the coming decades as the number of older adults increases. The increasing complexity of modern families, where asset disposition is sensitive and complicated, may lead to feelings of rejection and injustice and result in more challenges. Finally, the high prevalence of cognitive impairment and dementia in older adults creates a fertile environment for challenges to wills. It therefore behooves psychiatrists and other experts to be aware of the legal, medical, and psychiatric issues that underlie the assessment of testamentary capacity and the role of undue influence—two concepts that are inextricably linked and often combined in legal challenges to wills.

The psychiatric issues related to retrospective challenges of testamentary capacity (see reference 2 for a recent review) also apply to contemporaneous assessments. In this article, we focus on these issues as well as their specific relationship to undue influence. Our discussion proceeds largely from a psychiatric viewpoint, but we also briefly review the legal constructs of capacity and undue influence. Finally, we review some clinical issues that are relevant to the understanding of the mental state of an individual whose will is being challenged and relate these to the case example.

Construct of Testamentary Capacity

A testator (male) or testatrix (female) is the person who is executing a will; here we use the term testator in a general sense for both genders. Testamentary capacity refers to the legal status of being capable of executing a will. All mental capacities are determined by two fundamental components: an ability to understand the relevant facts and an appreciation of the consequences of taking or not taking specific actions.

Testamentary capacity, as defined in Common Law and U.S., Canadian, and English jurisdictions, addresses its task-specific nature as opposed to the global status of mental illness (3 , 4) . In Banks v. Goodfellow , a commonly cited English case (5) , John Banks, the testator, clearly suffered from a chronic and serious mental disorder but was deemed capable with respect to the execution of his will because his delusions did not affect the distribution of his assets. The Banks v. Goodfellow criteria are outlined in Table 1 .

In U.S. jurisdictions, the definition of testamentary capacity is similar except that the doctrine of insane delusion is distinct from general testamentary capacity. Thus, it is possible for a testator to possess general testamentary capacity and yet suffer from an insane delusion that invalidates the will (6 , 7) .

Testamentary capacity, like other capacities, is not only task specific but also situation specific. On occasion, U.S. cases have explicitly articulated this principle, either with the term “situation specific” or, more commonly, by referring to the complexity of the testator’s situation or the general need to consider all facts and circumstances in determining testamentary capacity (8) . While these issues have not been well researched with respect to the assessment of testamentary capacity, they have been addressed in the literature on many other capacities, including capacity to consent to treatment (9 , 10 , 11) . In one model, specific legal standards (thresholds) for the determination of consent to treatment were extracted from case law and informed by the forensic psychiatry literature. These legal standards serve to incorporate situation-specific factors into the assessment of capacity, with thresholds increasing as the situation becomes more complicated ( Figure 1 ).

Although these legal standards were developed primarily in relation to the issue of consent to treatment, the principles that underlie them are potentially applicable to other complex capacities, such as testamentary capacity. In a simple, uncomplicated situation, the standard would be “simply evidencing a choice”; a higher standard would involve “showing appreciation of consequences”; and in a highly complex conflictual environment, a testator may have to reach an even higher legal standard, namely, “the provision of rational reasons expressed clearly and consistently.” For example, there would be significant concern when an extremely wealthy testator with even mild cognitive impairment distributes a huge estate with significant implications within an environment that is rife with conflict and complex family dynamics. This would contrast with a much simpler situation-specific circumstance in which the testator was a retired pensioner with mild cognitive impairment living with his wife of many years in a stable relationship in an uncomplicated family situation.

Previous work (2 , 12) has outlined “suspicious circumstances” that call for careful and detailed probing and documentation of rationale for disposition of assets in the preparation of a will. These circumstances, identified in an empirical review of a large series of testamentary cases, negate the presumption of capacity that often prevails (13) . Not all U.S. jurisdictions apply the presumption of capacity to wills, but those that do not, achieve an equivalent result by applying minimal standards to determine whether the will proponent has proved testamentary capacity (14) . “Undue influence” is a subcategory within suspicious circumstances.

Suspicious circumstances in the context of a challenge to a will include a radical change from previous consistently expressed wishes; evidence of a concurrent mental or neurologic disorder that may affect cognition, judgment, impulsivity, or reality testing; a dependent situation whereby the testator is particularly vulnerable to influence or even suggestion; multiple changes in the will made by the testator as a means of controlling individuals who are perceived as essential to the testator’s dependence or well-being.

Construct of Undue Influence

Undue influence is a strictly legal concept; the onus of proof is on those claiming undue influence. Frolik (15) and Spar and Garb (16) have attempted to delineate the indications of undue influence, which are summarized in Table 2 . Frolik argues that the doctrine of undue influence allows the courts to maintain a relatively low threshold for testamentary capacity and hence to preserve the principle of autonomy and individual freedom with respect to the distribution of one’s assets. This is exemplified in a situation that is relatively uncomplicated and unconflicted. In such a situation, a testator with moderate cognitive impairment could still be considered to have testamentary capacity. However, if the circumstances are more complex or there is a suggestion of undue influence, the legal threshold becomes higher and calls for more careful probing of rationale at the time of the execution of the will.

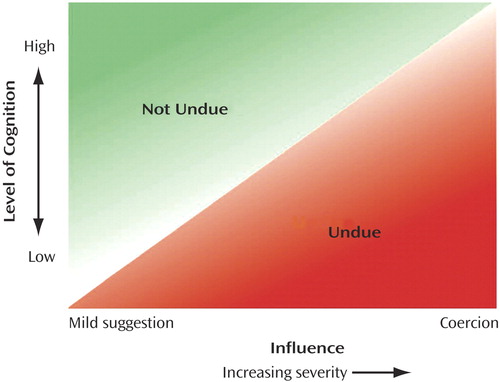

Historically, the notion of undue influence emphasized the concept of coercion, whereas subversion of will seems a more appropriate term. Subversion allows for a continuum of influence depending on the extent of cognitive impairment. The relationship between cognitive capacity and the notion of influence is illustrated in Figure 2 . The lower the capacity or cognitive status of an individual, the less influence would be required to determine that the individual was incapable or unduly influenced. Conversely, an individual with only mild impairment of cognitive function would have to be subjected to a severe level of influence to the point of coercion or containment before that influence would be considered undue.

Role of the Expert Witness or Assessor

At the time of the drafting of the will, lawyers make an initial assessment of testamentary capacity but may call upon experts to assist in specific circumstances. Experts may include neuropsychiatrists, geriatric psychiatrists, neuropsychologists, and others with a particular interest in capacity determinations. The role of the expert may involve confirmation of testamentary capacity when cognition or mental state is a concern. Similarly, experts may be asked to assess the potential role of undue influence. After the death of the testator, the will may be challenged, and experts can be called upon to give a retrospective opinion regarding capacity or undue influence. These assessments should always be made in the context of a careful review of available information, such as direct interview with the testator when alive, interviews with persons who had firsthand contact and experience with the testator, reviews of medical records, examinations for discovery, and legal documents. The expert should be able to formulate a comprehensive outline of clinical and environmental factors for consideration and offer an opinion for the court to consider. Ultimately, the court will make a decision based on a review of the evidence provided by the parties and witnesses as well as the expert opinion. Unfortunately, the case law on testamentary capacity is highly variable (17) , and there is no standardized forensic assessment instrument for this capacity.

The assessment of the environment (situation-specific factors) is important in the ultimate determination of capacity and of the impact of the influences that may have been brought to bear on the individual at the particular time in question. Thus, in the common situation where both testamentary capacity and undue influence are being considered, the fundamental question is whether an individual has the task-specific capacity to execute a will in the context of a specific environment. It is this complex interrelationship that should be the focus of assessments. Where suspicious circumstances exist, the assessor must inquire into specific areas (see below) but also assess higher-level cognition by probing the testator’s rationale for decisions as well as the testator’s appreciation of his or her circumstances and the impact of the distribution of his or her assets.

Documentation for Assessment of Testamentary Capacity and Undue Influence

In the absence of a validated assessment instrument, we propose that in addition to the traditional Banks v. Goodfellow criteria, the following issues should be addressed and documented in a forensic assessment, whether it is contemporaneous or retrospective:

Rationale for any dramatic changes or significant deviations from the pattern identified in prior wills or previous consistently expressed wishes regarding disposition of assets.

The appreciation of the consequences and impact of a particular distribution, especially if it deviates from or excludes “natural” beneficiaries, such as close family members or spouses.

Clarification of concerns about potential beneficiaries who are excluded from the will or bequeathed lower amounts than might have been expected—that is, ruling out the presence of a specific delusion or overvalued idea that influences the distribution.

Evidence of the presence of a specific neurologic or mental disorder that may affect cognition, judgment, or impulse control.

Evidence of behavioral disturbances or psychiatric symptoms at the time of the execution of a will, for example, behavioral and psychological symptoms of dementia such as agitation, impulsiveness, disinhibition, aggression, hallucination, and delusions.

The emotional/psychological milieu in which the testator lives, with specific reference to conflicts or tensions within the family, documenting the complexity and conflictual level of situation-specific factors.

The testator’s understanding and appreciation of any conflicts or tensions in his or her environment.

Evidence of a pathological or dependent relationship with a formal or informal caregiver, such as a younger woman who offers comfort and reassurance or plants seeds of suspiciousness toward family or friends.

Evidence of inconsistency in expressed wishes or an inability to communicate a clear, consistent wish with respect to the distribution of assets; for example, frequent will changes are sometimes made in a desperate attempt to garner care, support, or comfort at a time when the testator feels increasingly vulnerable or threatened.

Any of the indications of undue influence.

Specific questions posed to the testator may help in elucidating and probing the relationship between task-specific and situation-specific factors:

Can you tell me the reason(s) that you decided to make changes in your will?

Why did you decide to divide the estate in this particular fashion?

Do you understand how individual A might feel, having been excluded from the will or having been given a significantly less amount than previously expected or promised?

Do you understand the economic implications for individual B of this particular distribution in your will?

Can you tell me about the important relationships in your family and others close to you?

Can you describe the nature of any family or personal disputes or tensions that may have influenced your distribution of assets?

When a retrospective assessment is being conducted, assiduous review of medical records, examinations for discovery, and selective interviews of informants are needed to cast light on these issues.

Common Psychiatric Conditions That Can Affect Capacity and Vulnerability to Undue Influence

The conditions discussed below may affect cognition or perception, which in turn may have an effect on an individual’s ability to understand relevant facts related to testamentary capacity. These conditions may affect the person’s appreciation of consequences of specific actions or his or her interpretation of situation-specific factors. The expert clinician can help the lawyer or the courts by confirming the presence of these psychiatric conditions.

Dementias

Dementias such as Alzheimer’s disease, Lewy body dementia, and vascular cognitive impairment are characterized by diffuse cognitive deficits. In cases of obvious and severe cognitive impairment, there will be little need for subtle interpretations of brain function, and lawyers or the courts can assess the impact of the impairment without the help of experts. However, in many disputed cases, the level of cognitive impairment is relatively mild or subtle. Some individuals with dementia maintain their social graces and appear perfectly normal to the layperson. Therefore, probing and documentation of rationale for disposition, particularly in suspicious circumstances, are especially important to demonstrate that the individual is capable. In dementia, executive impairment is particularly important, as it can affect insight, perception, judgment, and impulse control. Mild forms of memory impairment can be associated with suspiciousness or even paranoid delusions as testators attempt to compensate for their memory deficits. In retrospective assessments, evidence for the progression of dementia after the last will was executed can help to support hypotheses about impaired thinking, perception, or judgment at the time of the execution of the will. While there is some evidence that courts have developed principles relevant to Alzheimer’s and other dementias, a deeper and wider knowledge base among jurists surely will enhance the law’s ability to adjudicate will contests (18) .

Alcohol

Alcoholism and alcohol abuse can have both acute and chronic effects on cognition, judgment, and behavior. In the acute phase of alcohol consumption, even small amounts of alcohol may affect perception, judgment, and impulsiveness. These mental changes could affect the testator’s decisions regarding the execution of a will. This was reflected in a case series in which substantive changes to the testator’s will closely preceded a suicide associated with alcohol abuse (19) . The effects of chronic alcohol abuse are similar to those described above for dementias. Without clearer guidance, however, courts and juries may not obtain a sufficient understanding of this type of impairment (20) .

Mood Disorders

Mood disorders, including depression and bipolar disorder, may produce cognitive distortions (delusions), compromise judgment, and cause irritability or impulsiveness. These acute or subacute changes may affect testamentary capacity and vulnerability to undue influence. Usually these changes in mental state can be identified during a specific episode, but in some cases they can become chronic.

Delusions

Paranoid delusions may be secondary to a number of clinical syndromes, including schizophrenia, delusional disorders, and other forms of neurologic disease, such as dementia, delirium, acquired brain injury, and other brain lesions. According to the Banks v. Goodfellow criterion, the testator must be free of any delusions that directly affect the distribution of the estate. Changes made in a will on the basis of a false belief make the will invalid. Even if such beliefs do not reach delusional intensity, they can make the testator vulnerable to undue influence. Careful questioning and probing by the assessor (medical or legal) will help to elicit the impact of these beliefs on the distribution of assets.

Common Cognitive Screening Tests

Clinicians tend to use a small number of cognitive screening tests that may be referred to in medical records or expert reports. These tests assess higher-level brain functions that control initiative, motivation, planning, impulse control, capacity for abstract thinking, and the exercise of judgment. The identification of subtle impairment of these functions in the context of a complex environment could easily produce a vulnerability to undue influence and affect testamentary capacity (21) . Assessors of testamentary capacity and undue influence and the courts must be able to interpret the significance of these commonly used tests. Clinicians and legal experts must understand that cognitive tests are not diagnostic of dementia and cannot be used as a measure of capacity. Their value lies in the ability to screen for cognitive impairment and to reflect changes in cognition over time. The Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE) and the clock-drawing test are the two most commonly used cognitive screening tests (22) .

The Mini-Mental State Examination

The MMSE is by far the most commonly used cognitive screening examination in the world. It includes seven cognitive domains or functions (23) , with a total possible score of 30: orientation to time (5 points), orientation to place (5 points), registration of three words (3 points), attention and calculation (5 points), recall of three words (3 points), language (8 points), and visuospatial ability (1 point).

The limitations of the MMSE include the fact that it does not test specifically for frontal or executive brain functions. The MMSE is heavily weighted toward orientation, short-term memory, and language skills. Nonetheless, the MMSE score has come to be used as a shorthand for the severity of cognitive dysfunction, and thus it is important that lawyers and clinicians understand the uses and limitations of the instrument and its scoring. The score alone is not necessarily a reflection of dementia or clinically significant cognitive impairment (24) . Scores below 26 suggest that a person is impaired. However, the MMSE score may be significantly influenced by factors such as native language, education, and premorbid IQ.

The Clock-Drawing Test

The clock-drawing test, which has been widely used as a cognitive screening instrument (25) , consists of a standardized circle with the instruction “This is a clock face; please put in the numbers so that it looks like a clock.” The patient is then instructed to “set the time to 10 past 11.” This test is useful as a cognitive screen because it subsumes many different brain functions covering a wide range of intellectual and perceptual skills: comprehension; planning; visual memory and reconstruction of a graphic; visuospatial abilities; motor programming and execution; numerical knowledge; abstract thinking (semantic instruction); inhibition of the tendency to be pulled by perceptual features of the stimulus (i.e., the “frontal pull” of the hands to “10” in the instruction “10 past 11”); concentration; and frustration tolerance.

The mix of visuospatial abilities as well as executive control functions makes the clock-drawing test particularly useful as a cognitive screening instrument. Although various methods of scoring and interpretation have been proposed, the test’s qualitative merits and simple global assessment are considered more important than complex scoring systems (25) .

SUMMARY AND RECOMMENDATIONS

In the case described, there are a number of suspicious circumstances, including a dramatic change in Mr. A’s last will from previous wills and from wishes that had previously been consistently expressed to his stepdaughter. There was an unnatural disposition involving an estranged stepson who appeared at the last minute. In addition, there are concerns about Mr. A’s cognition, perception, and judgment, given evidence of early cognitive impairment that was later confirmed as a dementia only 1 year after the execution of the last will.

Whether in retrospect one would declare the testator incapable purely because of cognitive issues is questionable. However, in light of the clear vulnerability caused by Mr. A’s early dementing illness, the impact of influence becomes much greater given that the beneficiary initiated the procurement of the will and gained undue benefit compared with the devoted stepdaughter. It seems likely that the stepson took advantage of Mr. A’s paranoid thinking, which was directed at the stepdaughter because of the perceptual distortions secondary to Mr. A’s dementing illness. Even though this was a retrospective assessment, the evidence appeared to be sufficiently strong to form an opinion on this question for the courts to consider and ultimately to determine.

The assessment of testamentary capacity and its interrelationship with vulnerability to undue influence bring together the medical and legal domains. The psychiatric and medical experts’ role is primarily to help lawyers and the courts make the best determination of testamentary capacity and to assess the role of undue influence. As the number of older people increases in the coming years, clinicians will likely be involved in these determinations with increasing frequency. Research in this area is needed, and it should involve a collaboration of the medical and legal domains to provide clearer guidelines for the assessment of these complex issues in individual cases (26) . Increased awareness within the legal profession of the importance of establishing testamentary capacity at the time of the execution of a will may lead to a greater demand for contemporaneous assessments and possibly avoid a court challenge at the time the will is brought for probate. Proposals to develop “lifetime capacity assessments” for this purpose merit exploration (17) .

1. Araujo v Neto, 2001, BCSC 935, 40 ETR (2d) 169Google Scholar

2. Shulman KI, Cohen CA, Hull I: Psychiatric issues in retrospective challenges of testamentary capacity. Int J Ger Psychiatry 2005; 20:63–69Google Scholar

3. Burns v Marshall, 767 So 2d 347, 353 (Ala 2000)Google Scholar

4. Matter of Khazaneh, NYS 2d, 2006 WL 3872843 (NY Sur), NY Slip Op 26547Google Scholar

5. Banks v Goodfellow, 1870, LR5 QB 549Google Scholar

6. In re Honigman’s Will, 168 NE 2d 676 (NY 1960)Google Scholar

7. American Law Institute: Restatement of the Law, Third: Property (Wills and Other Donative Transfers). Philadelphia: American Law Institute, 2003, section 8.1Google Scholar

8. Estate of Frisch, 5984 A 2d 1367, 1371 (NJ Super 1991)Google Scholar

9. Marson DC, McInturff B, Hawkins L, Bartolucci A, Harrell LE: Consistency of physician judgments of capacity to consent in mild Alzheimer’s disease. J Am Geriatr Soc 1997; 45:453–457Google Scholar

10. Marson DC, Earnst KS, Jamil F, Bartolucci A, Harrell LE: Consistency of physicians’ legal standard and personal judgment of competency in patients with Alzheimer disease. J Am Geriatr Soc 2000; 48:911–918Google Scholar

11. Grisso T: Evaluating Competencies: Forensic Assessments and Instruments. New York, Kluwer Academic Press/Plenum Publishers, 2003Google Scholar

12. Hull R, Hull I: Suspicious circumstances in relation to testamentary capacity and undue influence, in Estates: Planning, Administration, and Litigation. Law Society of Upper Canada, Special Lectures. Toronto, Carswell, 1996, pp 77–87Google Scholar

13. Appelbaum P, Roth L: Clinical issues in the assessment of competence. Am J Psychiatry 1981; 138:1462–1467Google Scholar

14. Atkinson TN, Handbook of the Law of Wills, 2nd ed. St Paul, Minn, West Publishing Company, 1953, pp 545–548Google Scholar

15. Frolik LA: The strange interplay of testamentary capacity and the doctrine of undue influence: are we protecting older testators or overriding individual preferences? Int J Law Psychiatry 2001; 24:253–266Google Scholar

16. Spar JE, Garb AS: Assessing competency to make a will. Am J Psychiatry 1992; 149:169–174Google Scholar

17. Champine P: Expertise and instinct in the assessment of testamentary capacity. Villanova Law Rev 2006; 51:25–94Google Scholar

18. Gorman WF: Testamentary capacity in Alzheimer’s disease. Elder Law Journal 1996; 4:225–246Google Scholar

19. Shulman KI, Hull IM, Cohen CA: Testamentary capacity and suicide: an overview of legal and psychiatric issues. Int J Law Psychiatry 2003; 26:403–415Google Scholar

20. Ex Parte Helms, 873 So 2d 1139, 1147 (Ala 2003)Google Scholar

21. Royall DR, Lauterbach EC, Cummings JL, Reeve A, Rummans TA, Kaufer DI, LaFrance WC Jr, Coffey CE: Executive control function: a review of its promise and challenges for clinical research. J Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci 2002; 14:377–405Google Scholar

22. Shulman KI, Herrmann N, Brodaty H, Chiu H, Lawlor B, Ritchie K, Scanlan JM: IPA survey of brief cognitive screening instruments. Int Psychogeriatrics 2006; 18:281–294Google Scholar

23. Folstein MF, Folstein SE, McHugh PR: “Mini-Mental State”: a practical method for grading the cognitive state of patients for the clinician. J Psychiatr Res 1975; 12:189–198Google Scholar

24. Landmark Trust v Goodhue, 782 A 2d 1219, 1226-27 (Vt 2001)Google Scholar

25. Shulman KI: Clock-drawing: is it the ideal cognitive screening test? Int J Ger Psychiatry 2000; 15:548–561Google Scholar

26. Peisah C: Reflections on changes in defining testamentary capacity. Int Psychogeriatrics 2005; 17:709–712Google Scholar