Eating Disorders: Hope Despite Mortal Risk

Eating disorders are still not considered a serious form of mental illness in some states and countries, resulting in a health care crisis for those currently suffering from these disorders, as well as their families (1) . This is puzzling, since there is considerable evidence that eating disorders are highly heritable, biologically based, severe mental disorders. As a prime example of the severity of these disorders, anorexia nervosa has consistently been shown to be associated with high morbidity and mortality. One review estimated the aggregate mortality rate at 0.56% per year, or approximately 5.6% per decade (2) .

It has not been certain, however, whether mortality rates are high for other eating disorders, such as bulimia nervosa and eating disorder not otherwise specified, the latter of which is the most common eating disorder diagnosis. In part, this is because it becomes difficult to locate patients and track their outcome over a long period. To circumvent such limitations, Crow and colleagues (3) analyzed data from all patients who presented for evaluation between 1979 and 1997 at a specialized eating disorder clinic at an academic medical center. In a longitudinal assessment of mortality reported on in this issue, the authors studied 1,885 individuals with anorexia nervosa (N=177), bulimia nervosa (N=906), or eating disorder not otherwise specified (N=802) over 8 to 25 years. A major strength of this outstanding study is that it avoids the usual limitations of follow-up studies of mortality because the investigators used computerized record linkage to the National Death Index, which provides vital status information for the entire United States, including cause of death extracted from death certificates.

Crow and colleagues found that crude mortality rates were 4.0% for anorexia nervosa, 3.9% for bulimia nervosa, and 5.2% for eating disorder not otherwise specified. Notably, all-cause standardized mortality ratios were significantly elevated for bulimia nervosa and eating disorder not otherwise specified, including suicide. As the authors note, it is well recognized that substantial medical complications are associated with vomiting, laxative abuse, and other purging behaviors. Moreover, the high suicide rate in bulimia nervosa is consistent with this disorder’s association with impulsivity and high comorbidity with mood, anxiety, and substance use disorders. In summary, the elevated mortality risks for bulimia nervosa and eating disorder not otherwise specified were similar to those for anorexia nervosa. These findings underscore the severity and public health significance of all types of eating disorders.

In another article in this issue, Steinhausen and Weber (4) comprehensively reviewed 79 studies consisting of 5,653 patients with bulimia nervosa to assess outcome, effect variables, and prognostic factors. Based on 27 of these studies, approximately 45% showed full recovery, whereas 27% improved considerably and 23% had a chronic protracted course. An earlier review by Steinhausen (5) found remarkably similar outcome statistics for anorexia nervosa. Using a series of cross-sectional data sets, the new study showed that the mean recovery rate from bulimia nervosa peaks in the interval of 4–9 years of follow-up and declines thereafter. Since longitudinal data were not used, it cannot be concluded that the developmental trajectory of bulimia nervosa is different from the course of anorexia nervosa, which showed a linear relationship indicating better outcome with increasing duration of follow-up. In fact, the few large longitudinal outcome studies of bulimia nervosa, using repeated assessments over an extended follow-up period, tend to provide a more favorable picture with increasing duration of follow-up.

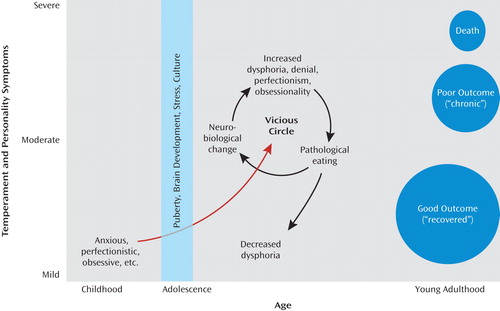

Together these papers add to recent developments in how we conceptualize the course and outcome of eating disorders ( Figure 1 ). Recent studies suggest that premorbid, genetically determined temperament and personality traits contribute to a vulnerability to developing anorexia nervosa and bulimia nervosa during adolescence in females (6 , 7) . State alterations secondary to pathological eating may sustain the illness and perhaps accelerate an out-of-control spiral in some patients. The Steinhausen studies support the contention that course and outcome may also show certain age-dependent patterns. Thus, a substantial number of patients may recover, in terms of remission of pathological eating and stabilization of weight, during their later teens or early 20s, although premorbid personality and temperament traits persist (8) .

a Childhood personality and temperament traits, which tend to be relatively mild, appear to contribute to a vulnerability to development of an eating disorder (7). Such traits may become intensified during adolescence as a consequence of the effects of multiple factors, such as puberty and gonadal steroids, development, stress, and cultural influences. For anorexia nervosa, there is a dysphoria-reducing character to dietary restraint (7, 9). In contrast, for bulimia nervosa, overeating is thought to relieve negative mood states (10–12). But chronic pathological eating leads to neurobiological changes that increase denial, rigidity, depression, anxiety, and other core traits, so that patients often enter a vicious circle. This results in a out-of-control downward spiral whereby a significant proportion of patients develop a chronic illness or die. Fortunately, a substantial portion of those with anorexia nervosa and bulimia nervosa recover by their early to mid-20s, although mild to moderate degrees of temperament and personality traits persist, often with positive attributes.

It is important to emphasize that these individuals—and their families—suffer for many years while symptomatic and, as the Crow et al. study (3) suggests, may be at risk of dying during this period of illness. Still, it is critical that insurance providers recognize that for many individuals, anorexia nervosa and bulimia nervosa do not constitute a black hole of endless treatment costs. In fact, appropriate treatment may keep people alive and healthy during the years that they are symptomatic. Such treatment counteracts the out-of-control spiral, minimizes medical complications, and presumably increases the likelihood of a good outcome. Moreover, many families get burned out during the seemingly endless struggles during the ill state. To prevent families from giving up, it is important to explain to them that many individuals with eating disorders do get better, but only after many years. Unfortunately, a subgroup of patients with eating disorders have a persistent chronic course and high mortality. Such findings raise the question of whether physiological factors contribute to outcome.

In this economic climate, there is a great need to find economical, effective therapies. Using an innovative and rigorous design, Peterson and colleagues (13) , reporting in this issue, compared three types of treatment for binge eating disorder. A total of 259 adults diagnosed with binge eating disorder were randomly assigned to a waiting list or to 20 weeks of therapist-led, therapist-assisted, or self-help group treatment. At end of treatment, the therapist-led (51.7%) and therapist-assisted (33.3%) conditions had higher binge eating abstinence rates than the self-help (17.9%) and waiting list (10.1%) conditions. However, no differences in abstinence rates were observed at the 6-month and 12-month follow-up assessments. Therapist-led group cognitive-behavioral treatment for binge eating disorder also led to greater reductions in binge eating frequency and lower attrition at end of treatment compared with group self-help treatment, although here too, no group differences were observed at the 6- and 12-month follow-ups. These findings suggest that self-help group treatment may be a viable alternative to therapist-led interventions in some settings. It should be noted, however, that the power of such treatments may be limited since many patients continued to have substantial degrees of binge behaviors at 12-month follow-up. Clearly, we still have much to learn about providing truly effective treatments for eating disorders.

1. Klump K, Bulik C, Kaye W, Treasure J, Tyson E: Eating disorders are serious mental illnesses. Int J Eat Disord 2009; 42:97–103Google Scholar

2. Sullivan PF: Mortality in anorexia nervosa. Am J Psychiatry 1995; 152:1073–1074Google Scholar

3. Crow SJ, Peterson CB, Swanson SA, Raymond NC, Specker S, Eckert ED, Mitchell JE: Increased mortality in bulimia nervosa and other eating disorders. Am J Psychiatry 2009; 166:1342–1346Google Scholar

4. Steinhausen H-C, Weber S: The outcome of bulimia nervosa: findings from one-quarter century of research. Am J Psychiatry 2009; 166:1331–1341Google Scholar

5. Steinhausen H-C: The outcome of anorexia nervosa in the 20th century. Am J Psychiatry 2002; 159:1284–1293Google Scholar

6. Lilenfeld L, Wonderlich S, Riso LP, Crosby R, Mitchell J: Eating disorders and personality: a methodological and empirical review. Clin Psychol Rev 2006; 26:299–320Google Scholar

7. Kaye W, Fudge J, Paulus M: New insight into symptoms and neurocircuit function of anorexia nervosa. Nat Rev Neurosci 2009; 10:573–584Google Scholar

8. Wagner A, Barbarich-Marsteller NC, Frank GK, Bailer UF, Wonderlich SA, Crosby RD, Henry SE, Vogel V, Plotnicov K, McConaha C, Kaye WH: Personality traits after recovery from eating disorders: do subtypes differ? Int J Eat Disord 2006; 39:276–284Google Scholar

9. Vitousek K, Manke F: Personality variables and disorders in anorexia nervosa and bulimia nervosa. J Abnorm Psychol 1994; 103:137–147Google Scholar

10. Abraham S, Beaumont P: How patients describe bulimia or binge eating. Psychol Med 1982; 12:625–635Google Scholar

11. Johnson C, Stuckey M, Lewis L, Schwartz D: Bulimia: a descriptive survey of 316 cases. Int J Eat Disord 1982; 2:3–16Google Scholar

12. Kaye WH, Gwirtsman HE, George DT, Weiss SR, Jimerson DC: Relationship of mood alterations to bingeing behaviour in bulimia. Br J Psychiatry 1986; 149:479–485Google Scholar

13. Peterson CB, Mitchell JE, Crow SJ, Crosby RD, Wonderlich SA: The efficacy of self-help group treatment and therapist-led group treatment for binge eating disorder. Am J Psychiatry 2009; 166:1347–1354Google Scholar