The Relationship Between Depressive Personality Disorder and Major Depressive Disorder: A Population-Based Twin Study

Abstract

Objective: One of the most important controversies regarding depressive personality disorder is the overlap with mood disorders. The aim of this study was to estimate the genetic and environmental sources of covariance between depressive personality disorder and major depressive disorder and to what extent genetic, shared, and unique environmental factors are specific to each disorder. Method: A total of 2,801 young adult twins from the Norwegian Institute of Public Health Twin Panel were assessed at personal interview for depressive personality disorder and major depressive disorder with the Structured Interview for DSM-IV Personality and the Composite International Diagnostic Interview. Bivariate Cholesky models were fitted to the data by using the Mx statistical program. Results: In the best-fitting model, the covariation between depressive personality disorder and major depressive disorder were accounted for by genetic and unique environmental factors only. A model that did not include genetic factors specific to major depressive disorder was rejected. The authors found no clear evidence for gender differences in sources of comorbidity of depressive personality disorder and major depressive disorder. Conclusions: Although depressive personality disorder and major depressive disorder share a substantial proportion of genetic and environmental risk factors, the results from this study support the hypothesis that the two disorders are distinct entities with overlapping, but not identical, etiologies.

Depressive personality disorder was first formally introduced in the fourth version of DSM and was included in Appendix B among other diagnostic categories in need of further study. The personality disorder work group for DSM-IV outlined research areas for depressive personality disorder (1) , one of the most important being the potential overlap between depressive personality disorder and mood disorders. Several studies have addressed this issue (2 – 7) , most finding substantial overlap between depressive personality disorder and both dysthymic disorder and major depressive disorder. However, although two studies used small nonclinical samples (5 , 7) , none were population-based.

Moderate to substantial heritability has been demonstrated for major depressive disorder (8 , 9) and recently also for depressive personality disorder (10) . Previous studies have found that depressive personality and mood disorders coaggregate in families (4 , 7 , 11 – 14) . However, family studies cannot distinguish between genetic and shared environmental causes of familiar aggregation. Bivariate twin studies can determine to what extent coaggregation of disorders results from genetic or common environmental factors (15) . To our knowledge, this has never been explored for depressive personality disorder and mood disorders.

In this study, we sought to determine the sources of co-occurrence between depressive personality disorder and major depressive disorder in a population-based sample of Norwegian twins. Specifically, we estimated to what extent these disorders shared the same genetic and environmental risk factors.

Method

Sample

The Norwegian Institute of Public Health Twin Panel includes twins identified through information in the National Medical Birth Registry, established Jan. 1, 1967, which receives mandatory notification of all live and stillbirths of at least 16 weeks’ gestation. The current panel includes information on 15,370 like- and unlike-sexed twins born from 1967 to 1979. Two questionnaire studies have been conducted, in 1992 (twins born 1967–1974) and in 1998 (twins born 1967–1979). Altogether, 12,700 twins received the second questionnaire, and 8,045 responded (response rate=63%). The sample included 3,334 pairs and 1,377 single responders. The Norwegian Institute of Public Health Twin Panel is described in detail elsewhere (16) .

Data for this report derive from an interview study of axis I and axis II psychiatric disorders, which began in 1999. The participants were recruited among 3,153 complete pairs who in the second questionnaire agreed to participate in the interview study and 68 drawn directly from the Norwegian Institute of Public Health Twin Panel. Of these 3,221 eligible pairs, 0.8% were unwilling or unable to participate, and in 16.2% of the pairs, only one twin agreed to the interview. After two contacts requesting participation (the maximum number of contacts allowed in the approval obtained from the Regional Committee for Medical Research Ethics), 38.2% did not respond. Altogether, 2,801 twins (44% of those eligible) were interviewed.

Zygosity was initially determined by questionnaire items previously shown to categorize correctly 97.5% of the pairs (16 , 17) . In all but 385 like-sexed pairs, zygosity was also determined by molecular methods based on the genotyping of 24 microsatellite markers. Seventeen of these pairs with DNA information (2.5%) were found to be misclassified by the questionnaire data and were corrected. From these data, we estimate that in our entire sample zygosity misclassification rates were under 1%, a rate that is unlikely to substantially bias results (18) .

Approval was received from the Norwegian Data Inspectorate and the Regional Ethical Committee, and written informed consent was obtained from all participants after complete description of the study.

Measurements

A Norwegian version of the Structured Interview for DSM-IV Personality (19) was used to assess personality disorders. This instrument is a comprehensive semistructured diagnostic interview for the assessment of all DSM-IV axis II diagnoses, including nonpejorative questions organized into topical sections rather than by disorders. This allows for a natural flow and increases the likelihood that useful information from related questions may be taken into account when rating related criteria. The specific DSM-IV criterion associated with each set of questions is rated with the following scoring guidelines: 0=“not present or limited to rare isolated examples,” 1=“subthreshold—some evidence of the trait but not sufficiently pervasive to consider the criterion present,” 2=“present—criterion is clearly present for most of the last 5 years,” 3=“strongly present.” The Structured Interview for DSM-IV Personality uses the “5-year rule,” meaning that the behavior, cognitions, and feelings predominating for most of the last 5 years are considered to be representative of the individual’s long-term personality functioning. The interview is conducted after the axis I interview, which helps the interviewer to distinguish more easily longstanding behavior reported by the subject from temporary states owing to an episodic psychiatric disorder.

The interviewers were mostly psychology students in their final part of training and experienced psychiatric nurses. They were trained by professionals (one psychiatrist and two psychologists) with extensive previous experience with the instrument and closely followed up individually during the data-collection period. Interrater reliability for depressive personality disorder was assessed by two raters scoring 70 audiotaped interviews. The number of subjects with categorically classified personality disorders was too low to calculate kappa coefficients. Instead, intraclass correlations for the scaled personality disorders were used. The correlation for depressive personality disorder was 0.96 if subthreshold criteria were included and 0.78 if a positive criterion was defined as a score of ≥2.

Axis I disorders were assessed with the Norwegian version of the computerized Munich Composite International Diagnostic Interview (CIDI) (20) , a comprehensive structured diagnostic interview for the assessment of DSM-IV axis I diagnoses and ICD-10 diagnoses. The CIDI has been shown to have good test-retest and interrater reliability (21 , 22) . The interviewers received a standardized training program for CIDI by teachers certified by the World Health Organization and were supervised closely during the data-collection period.

The interviews were carried out between June 1999 and May 2004 and were largely conducted face-to-face (231 interviews, 8.3%, were conducted by telephone). Twins in each pair were interviewed by different interviewers.

Statistics

Categorical diagnoses of depressive personality disorder and major depressive disorder based on DSM-IV were used for prevalence estimates. However, in this population-based sample of twins, the prevalence of categorical diagnoses of depressive personality disorder was too low to permit useful twin analyses. We used a dimensional approach (23) , constructing an ordinal variable based on the number of endorsed criteria. To optimize statistical power and produce maximally stable results, we used the number of endorsed subthreshold criteria (≥1) instead of criteria above threshold (≥2), assuming that the liability for each trait is continuous and normally distributed, i.e., that the classification 0–3 represents different degrees of severity. This assumption was evaluated with multiple threshold tests for each criterion. The same procedure was used to test the assumption that the number of positive criteria for depressive personality disorder represents different degrees of severity. All of the multiple threshold tests were done separately for each zygosity group, and none was significant (all p>0.05). Because the number of subjects who endorsed all or most of the criteria for a disorder was small, we collapsed the upper categories (four to seven criteria fulfilled) for the summed score, resulting in ordinal variables that included five categories.

In the classical twin model, individual differences in liability are assumed to arise from three latent factors: additive genetic (A) effects, common or shared environment (C) effects that include all environmental exposures shared by the twins and contribute to their similarity, and individual-specific or unique environment (E) effects that include all environmental factors not shared by the twins plus measurement error. Because monozygotic twins share all their genes and dizygotic twins share on average 50% of their segregating genes, A contributes twice as much to the resemblance in monozygotic compared to dizygotic twins for a particular trait or disorder. Both monozygotic and dizygotic twins are assumed to share all their C factors and none of their E factors.

Model fitting was performed with the software package Mx (24) . To test the degree to which the covariation between major depressive disorder and depressive personality disorder resulted from common factors, we applied a bivariate Cholesky structural equation model (25) , specifying three latent factors (A 1 , C 1 , and E 1 ) influencing both depressive personality disorder and major depressive disorder in addition to three factors (A 2 , C 2 , and E 2 ) accounting for residual influences specific to major depressive disorder. The choice of ordering was based on the assumption that depressive personality disorder is a long-standing trait developing early in life, whereas major depressive disorder has a later age of onset. The bivariate Cholesky model allows for testing possible scalar sex differences in genetic and environmental sources of covariance (26) , as well as calculating the correlations between genetic factors (r a ), shared environmental factors (r c ), and individual-specific environmental factors (r e ) that influence the two phenotypes.

A full model (ACE) including all latent variables and in which the genetic correlations for men and women were constrained to be equal was tested against nested submodels with reduced numbers of parameters. The fit of the alternative models can be compared with the difference in twice the log likelihood, which, under certain regularity conditions, is asymptomatically distributed as χ 2 with degrees of freedom equal to the difference in number of parameters (Δχ 2 test). According to the principle of parsimony, models with fewer parameters are preferable if they do not result in a significant deterioration of fit. An alternative method for model comparison that combines parsimony with explanatory power is Akaike’s information criterion (27) , calculated as Δχ 2 –Δ2df.

Twin studies rely upon the assumption that monozygotic and dizygotic pairs are equally exposed to environmental influences on the trait or disorder under study. We tested the validity of this assumption by applying polychotomous logistic regression with control for the correlational structure of our data using independent estimating equations as operationalized in the SAS procedure GENMOD (28) .We tested child contact (mean years in class together and years lived together) and adult contact (current frequency of phone contact, frequency of personal contact, and living proximity) and controlled for shared environment effects, genetic effects, age, sex, and zygosity. We tested whether the depressive personality disorder trait score/major depressive disorder in twin 1 interacted with the measure of contact to predict depressive personality disorder trait score/major depressive disorder in twin 2. A violation of the EEA would predict that twin 1’s depressive personality disorder trait score/major depressive disorder would be a better predictor of twin 2’s depressive personality disorder trait score/major depressive disorder in twins with high versus low contact. We found no significant effects of child or adult contact on depressive personality disorder traits or on major depressive disorder (p values for all interaction terms exceeded 0.10).

Results

Our final sample consisted of 2,801 participants, 1,777 women and 1,024 men. Of these, 2,790 completed both interviews, including the following numbers of complete pairs: 220 monozygotic males, 116 dizygotic males, 448 monozygotic females, 261 dizygotic females, 339 of the opposite sex, and 19 single responders. The mean age of the respondents was 28.1 years (range=19–36). Fifty-five (2.0%, 48 women and seven men) fulfilled the criteria for depressive personality disorder, and 394 (14.1%, 281 women and 113 men) had a lifetime history of major depressive disorder. Twenty-eight subjects with depressive personality disorder (50.9%) had a lifetime diagnosis of major depressive disorder, and 7.2% of those with major depressive disorder had depressive personality disorder (odds ratio=6.7, 95% confidence interval [CI]=3.9–11.3). One hundred and eighty-six (48.1%) of the subjects with major depressive disorder did not meet any of the seven depressive personality disorder criteria.

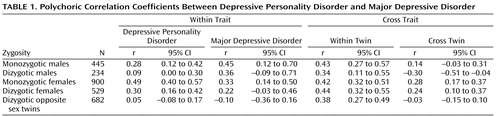

Polychoric correlation coefficients for depressive personality disorder and major depressive disorder for all five zygosity groups are given in Table 1 . Within individuals, liability to the two disorders was substantially correlated (column 7). The cross-twin correlations for both disorders were higher in monozygotic than in dizygotic twins, suggesting genetic effects. The cross-twin cross-trait correlations (column 9) were also higher for monozygotic than for dizygotic twins, suggesting that both genetic and shared environmental factors might account for the observed correlation between depressive personality disorder and major depressive disorder. For both depressive personality disorder and major depressive disorder, polychoric correlations were lower in dizygotic opposite twins than in same-sex dizygotic pairs, suggesting sex differences. However, this was not the case for the cross-twin cross-trait correlations.

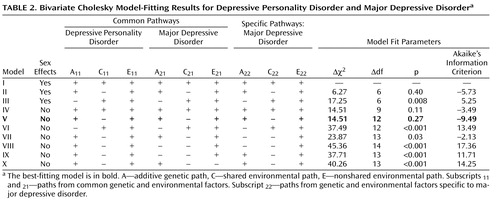

Table 2 displays the results of the model-fitting procedure. The full model (model 1) included all specified pathways from all latent variables (A 1 , C 1 , E 1 and A 2 , C 2 , and E 2 ) for depressive personality disorder and major depressive disorder and allowed path coefficients to differ between the sexes. In models II and III, we set to zero all shared environment and all of the genetic parameters, respectively. Model II resulted in an improvement of fit (Akaike’s information criterion=–5.73), whereas the model that included no genetic effects resulted in a deterioration in fit and was rejected by the χ 2 test. In the next set of models (models IV–X), we constrained the parameters to be equal in men and women (no sex effects). The AE model showed the lowest Akaike’s information criterion (–9.49) and had the overall best fit of those tested. The model with no specific A for major depressive disorder (model VII) fitted poorly. Dropping common A or common E resulted in models that were rejected by the χ 2 test.

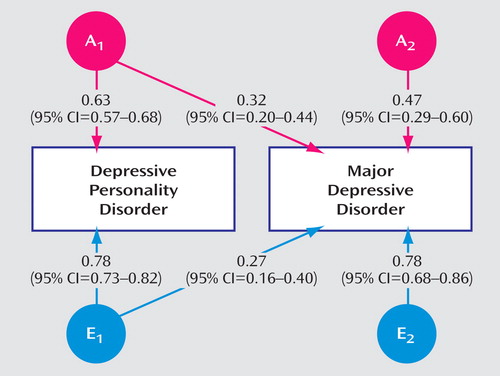

In the best-fitting model, r a (95% CI) was estimated to be 0.56 (95% CI=0.36–0.80), and r e was estimated at 0.33 (95% CI=0.20–0.44). This indicates that both genes and unique environmental experiences contribute to the comorbidity between depressive personality disorder and major depressive disorder.

Figure 1 shows the path coefficients for the best-fitting model. The parameter estimates for the two disorders can be calculated from the path coefficients. For depressive personality disorder, a 2 was 0.40 (0.63 2 ) and e 2 was 0.61 (0.78 2 ), and for major depressive disorder, a 2 was 0.32 (0.32 2 + 0.47 2 ) and e 2 was 0.68 (0.27 2 + 0.78 2 ). The correlation between the two disorders can be calculated as 0.63 × 0.32 + 0.78 × 0.27=0.41, which corresponds to the data given in Table 1 (column 5). Of note, genetic factors accounted for (48% [(0.63 × 0.28)/0.41] × 100) of this covariance and unique environmental factors the remaining 52%.

a A stands for additive genetic factors. E stands for unique environmental factors.

Discussion

The main aim of this study was to determine genetic and environmental sources of comorbidity between depressive personality disorder and major depressive disorder. The best-fitting model suggested that a substantial part of the covariation between the two disorders is accounted for by genes but also that major depressive disorder is influenced by genetic factors not shared with depressive personality disorder. We found no clear evidence for sex differences in genetic and environmental contributions to the comorbidity between depressive personality disorder and major depressive disorder.

To our knowledge, this is the first study to examine genetic and environmental sources of overlap between depressive personality disorder and major depressive disorder. We are aware of six family studies addressing the relationship between depressive personality disorder and axis I mood disorders: Klein (13) found an increase in bipolar disorder and major depressive disorder in the first-degree relatives of outpatients with depressive personality disorder and later replicated the latter finding in a population of undergraduates (7) . Cassano et al. (11) found that relatives of probands with depressive personality disorder and major depressive disorder had higher rates of mood disorders than relatives of those with major depressive disorder alone. Finally, McDermut et al. (4) found an increased risk of depression in relatives of patients with depressive personality disorder. Furthermore, two studies of patients with mood disorders found that their first-degree relatives had higher than expected prevalences of depressive personality disorder (12 , 14) . As noted, family studies cannot distinguish between genetic and shared environmental causes of familiar coaggregation. Lacking previous twin studies on depressive personality disorder and mood disorders, comparisons are restricted to studies on mood disorders and normal personality traits: depressive personality disorder correlated highly (0.50–0.75) with neuroticism in the five-factor model (29) . A strong correlation between neuroticism and depressive disorders is well established, and high levels of neuroticism predict later onset of major depressive disorder (30 – 32) . Two previous twin studies have shown that the co-occurrence of neuroticism and major depressive disorder is in part due to shared genetic factors, with genetic correlations of approximately 0.50–0.60 (30 , 31) . Our finding that common genetic factors also contribute to the covariance between depressive personality disorder and major depressive disorder agrees with these results.

Consistent with other studies of personality and depressive disorders, our best-fitting model did not include common environmental risk factors for depressive personality disorder and major depressive disorder. However, the power of the classical twin study when ordinal data are used is limited (33) . The data in Table 1 suggested that shared environmental effects could contribute to the correlation between depressive personality disorder and major depressive disorder. To further explore this, we tested a model that added common C to the best-fitting model. Although this model could not be rejected when compared to the full model, the parameter estimates for C were negligible (results available on request from the first author).

There was no sex difference in the magnitude of genetic and environmental contributions to the covariance of depressive personality disorder and major depressive disorder in our best-fitting model. We found evidence for gender differences in univariate analysis of depressive personality disorder in this sample (10) , but not for major depressive disorder (unpublished results). Although previous studies have shown conflicting results, the two largest studies to date have demonstrated gender differences for the heritability of depressive disorders as well (8 , 34) . The results regarding gender differences in the present sample must be interpreted with caution owing to the small number of dizygotic males and the low prevalence of depressive personality disorder.

There are several ways to explain the co-occurrence of multifactorial disorders (15) . In a cross-sectional study such as this, it is rarely possible to infer causality with high confidence. However, with such consistent findings of co-occurrence in a nonclinical sample, our findings cannot be due to selection bias. The mean age of onset of the first major depressive episode was 21.6 years (range=14–32). Personality disorders and traits are normally regarded as starting in late adolescence or early adulthood, so we may hypothesize that in most cases, depressive personality disorder or its traits were present before and thus may contribute to the onset of major depressive disorder (vulnerability model). On the other hand, we cannot rule out that personality pathology may, at least in part, be the consequence of prior episodes of major depression (scar model).

We tested the correlated liability model in which the co-occurrence of two or more disorders is due to overlapping risk-factors (15) and found that these consisted of both genetic and unique environmental factors. Depressive personality disorder and major depressive disorder could represent one more set of related psychiatric disorders that share, in part, the same genetic liability but manifest themselves differentially mainly as a consequence of environmental differences (35) . However, in contrast with findings from e.g., major depressive disorder and generalized anxiety disorder in which r a has been estimated at unity (36) , in the case of major depressive disorder and depressive personality disorder, it seems that about 50% of the genes involved contribute to one but not the other syndrome.

The results must be interpreted in light of five limitations. First, we would have wished to include bivariate analyses of depressive personality disorder and dysthymic disorder because this is the mood disorder regarded as having the most features in common with depressive personality disorder, but the prevalence was too low to permit useful twin analyses. However, we were able to examine recurrent major depression, although its low prevalence (men: 3.8%, women: 5.8%, total: 5.1%) made it impossible to explore sex effects. Since our best-fitting model for depressive personality disorder–major depressive disorder did not include sex differences, we tested bivariate models using recurrent major depressive disorder (defined as ≥two episodes) and specifying equal parameters for men and women. The best-fitting model was an AE model with parameter estimates very similar to those reported above (results available upon request from the first author). Second, a current depressive episode might have influenced the answers on personality traits (37) . However, the Structured Interview for DSM-IV Personality is based on how one usually regards oneself based on the last 5 years, and the interviewers are particularly trained to emphasize this. Furthermore, only 37 (9.4%) of the subjects with major depressive disorder reported having their last depressive episode within the previous 2 weeks, and 222 (56.3%) reported that it was more than 1 year since their last episode of major depression. Third, because of the low prevalence of depressive personality disorder, we did not examine the fully syndromal versions of this diagnosis. Instead, we examined a number of criteria using a low threshold of endorsement. Many have argued that personality disorders are best conceptualized as dimensional rather than dichotomous constructs (38) . Since twin analyses are based on the single liability threshold model, it should in principle make no difference if the variable studied is categorical or dimensional as long as the multiple threshold test indicates that this variable reflects the same liability that underlay the categorical diagnosis. The same argument applies to the threshold of endorsement used for the individual criteria, and the assumption that the liability for each criterion is continuous and normally distributed was supported by the multiple threshold test. We have previously found that heritability estimates for depressive personality disorder in women were the same regardless of whether the threshold ≥2 or ≥1 was used (10) . In the present study, reanalyses of the data with criteria threshold ≥2 and no sex effects yielded parameter estimates for the best-fitting AE model almost identical to the original model in which threshold ≥1 was used (results available on request from the first author). Fourth, although we included a large number of twins, substantial attrition was observed in this sample through three waves of contact consisting of two questionnaires and a personal interview. We report detailed analyses of the predictors of nonresponse elsewhere (unpublished work by Harris et al.). Cooperation was strongly and consistently predicted by female sex, monozygosity, older age, and higher educational status, but not symptoms of mental disorder. The second questionnaire included screening items for major depressive disorder and personality disorders. With control for demographic variables, the weighted scores for depressive personality disorder and major depressive disorder from the questionnaire did not predict participation in the personal interview. Fifth, these results were obtained from a particular sample of young Norwegians and may not be fully generalizable to other age cohorts or ethnic groups.

1. Phillips KA, Hirschfeld RM, Shea MT, Gunderson JG: Depressive personality disorder, in The DSM-IV Personality Disorders. Edited by Livesley WJ. New York, the Guilford, 1995, pp 287–302Google Scholar

2. Hirschfeld RM, Holzer CE III: Depressive personality disorder: clinical implications. J Clin Psychiatry 1994; 55(suppl):10–17Google Scholar

3. Klein DN, Shih JH: Depressive personality: associations with DSM-III-R mood and personality disorders and negative and positive affectivity, 30-month stability, and prediction of course of axis I depressive disorders. J Abnorm Psychol 1998; 107:319–327Google Scholar

4. McDermut W, Zimmerman M, Chelminski I: The construct validity of depressive personality disorder. J Abnorm Psychol 2003; 112:49–60Google Scholar

5. Ryder AG, Bagby RM, Dion KL: Chronic, low-grade depression in a nonclinical sample: depressive personality or dysthymia? J Personal Disord 2001; 15:84–93Google Scholar

6. Ryder AG, Schuller DR, Bagby RM: Depressive personality and dysthymia: evaluating symptom and syndrome overlap. J Affect Disord 2006; 91:217–227Google Scholar

7. Klein DN, Miller GA: Depressive personality in nonclinical subjects. Am J Psychiatry 1993; 150:1718–1724Google Scholar

8. Kendler KS, Gatz M, Gardner CO, Pedersen NL: A Swedish national twin study of lifetime major depression. Am J Psychiatry 2006; 163:109–114Google Scholar

9. Sullivan PF, Neale MC, Kendler KS: Genetic epidemiology of major depression: review and meta-analysis. Am J Psychiatry 2000; 157:1552–1562Google Scholar

10. Orstavik RE, Kendler KS, Czajkowski N, Tambs K, Reichborn-Kjennerud T: Genetic and environmental contributions to depressive personality disorder in a population-based sample of Norwegian twins. J Affect Disord 2007; 99:181–189Google Scholar

11. Cassano GB, Akiskal HS, Perugi G, Musetti L, Savino M: The importance of measures of affective temperaments in genetic studies of mood disorders. J Psychiatr Res 1992; 26:257–268Google Scholar

12. Klein DN, Clark DC, Dansky L, Margolis ET: Dysthymia in the offspring of parents with primary unipolar affective disorder. J Abnorm Psychol 1988; 97:265–274Google Scholar

13. Klein DN: Depressive personality: reliability, validity, and relation to dysthymia. J Abnorm Psychol 1990; 99:412–421Google Scholar

14. Klein DN: Depressive personality in the relatives of outpatients with dysthymic disorder and episodic major depressive disorder and normal controls. J Affect Disord 1999; 55:19–27Google Scholar

15. Neale MC, Kendler KS: Models of comorbidity for multifactorial disorders. Am J Hum Genet 1995; 57:935–953Google Scholar

16. Harris JR, Magnus P, Tambs K: The Norwegian Institute of Public Health Twin Panel: a description of the sample and program of research. Twin Res 2002; 5:415–423Google Scholar

17. Magnus P, Berg K, Nance WE: Predicting zygosity in Norwegian twin pairs born 1915–1960. Clin Genet 1983; 24:103–112Google Scholar

18. Neale MC: A finite mixture distribution model for data collected from twins. Twin Res 2003; 6:235–239Google Scholar

19. Pfohl B, Blum N, Zimmerman M: Structured Interview for DSM-IV Personality (SIDP-IV). Iowa City, University of Iowa, Department of Psychiatry, 1995Google Scholar

20. Wittchen HU, Pfister H: DIA-X Interviews (M-CIDI): Manual fur Screening-Verfahren und Interview: Interviewheft Langsschnittuntersuchung (DIA-X-Lifetime); Erganzungsheft (DIA-X-Lifetime); Interviewheft Querschnittuntersuchung (DIA-X 12 Monate); Erganzungsheft (DIA-X 12 Monate); PC-Programm zur Durchfuhrung des Interviews(Langs-und Querschnittuntersuchung); Auswertungsprogramm. Frankfurt, Austria, Swets & Zeitlinger, 1997Google Scholar

21. Wittchen HU: Reliability and validity studies of the World Health Organization–Composite International Diagnostic Interview (CIDI): a critical review. J Psychiatr Res 1994; 28:57–84Google Scholar

22. Wittchen HU, Lachner G, Wunderlich U, Pfister H: Test-retest reliability of the computerized DSM-IV version of the Munich—Composite International Diagnostic Interview (M-CIDI). Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol 1998; 33:568–578Google Scholar

23. Widiger TA, Samuel DB: Diagnostic categories or dimensions? a question for the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders—Fifth Ed. J Abnorm Psychol 2005; 114:494–504Google Scholar

24. Neale MC, Boker SM, Xie G, Maes HH: Mx: Statistical Modeling, 6th ed. Richmond, Va, Virginia Commonwealth University, Medical College of Virginia, 2003Google Scholar

25. Neale MC, Cardon LR: Methodology for genetic studies of twins and families. Dodrecht, the Netherlands, Klüver, 1992Google Scholar

26. Neale MC, Roysamb E, Jacobson K: Multivariate genetic analysis of sex limitation and G x E interaction. Twin Res Hum Genet 2006; 9:481–489Google Scholar

27. Akaike H: Factor-analysis and AIC. Psychometrica 1987; 52:317–332Google Scholar

28. SAS Institute: SAS Online Doc 9.1.3. Cary, NC, SAS Institute, 2005Google Scholar

29. Dyce JA, O’Connor BP: Personality disorders and the five-factor model: a test of facet-level predictions. J Personal Disord 1998; 12:31–45Google Scholar

30. Fanous A, Gardner CO, Prescott CA, Cancro R, Kendler KS: Neuroticism, major depression and gender: a population-based twin study. Psychol Med 2002; 32:719–728Google Scholar

31. Hettema JM, Neale MC, Myers JM, Prescott CA, Kendler KS: A population-based twin study of the relationship between neuroticism and internalizing disorders. Am J Psychiatry 2006; 163:857–864Google Scholar

32. Khan AA, Jacobson KC, Gardner CO, Prescott CA, Kendler KS: Personality and comorbidity of common psychiatric disorders. Br J Psychiatry 2005; 186:190–196Google Scholar

33. Neale MC, Eaves LJ, Kendler KS: The power of the classical twin study to resolve variation in threshold traits. Behav Genet 1994; 24:239–258Google Scholar

34. Kendler KS, Gardner CO, Neale MC, Prescott CA: Genetic risk factors for major depression in men and women: similar or different heritabilities and same or partly distinct genes? Psychol Med 2001; 31:605–616Google Scholar

35. Kendler KS, Prescott CA, Myers J, Neale MC: The structure of genetic and environmental risk factors for common psychiatric and substance use disorders in men and women. Arch Gen Psychiatry 2003; 60:929–937Google Scholar

36. Kendler KS: Major depression and generalised anxiety disorder: same genes, (partly) different environments—revisited. Br J Psychiatry Suppl 1996; 68–75Google Scholar

37. Lyle Stuart S, Simons AD, Thase ME, Pilkonis P: Are personality assessments valid in acute major depression? J Affect Disord 1992; 24:281–289Google Scholar

38. Skodol AE, Oldham JM, Bender DS, Dyck IR, Stout RL, Morey LC, Shea MT, Zanarini MC, Sanislow CA, Grilo CM, McGlashan TH, Gunderson JG: Dimensional representations of DSM-IV personality disorders: relationships to functional impairment. Am J Psychiatry 2005; 162:1919–1925Google Scholar