Posttraumatic Stress Disorder and Memory Problems After Female Genital Mutilation

Abstract

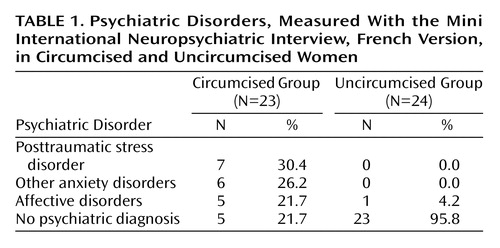

OBJECTIVE: This pilot study investigated the mental health status of women after genital mutilation. Although experts have assumed that circumcised women are more prone to developing psychiatric illnesses than the general population, there has been little research to confirm this claim. It was predicted that female genital mutilation is associated with a high rate of posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD). METHOD: The psychological impact of female genital mutilation was assessed in 23 circumcised Senegalese women in Dakar. Twenty-four uncircumcised Senegalese women served as comparison subjects. A neuropsychiatric interview and further questionnaires were used to assess traumatization and psychiatric illnesses. RESULTS: The circumcised women showed a significantly higher prevalence of PTSD (30.4%) and other psychiatric syndromes (47.9%) than the uncircumcised women. PTSD was accompanied by memory problems. CONCLUSIONS: Within the circumcised group, a mental health problem exists that may furnish the first evidence of the severe psychological consequences of female genital mutilation.

According to the World Health Organization definition (1), female genital mutilation (often referred to as “female circumcision”) “comprises all procedures involving the partial or total removal of the external female genitalia or other injury to the female genital organs whether for cultural, religious or other nontherapeutic reasons” (p. 25). The procedure is performed within a wide range of African ethnic groups. Appropriate estimations are that between 100 and 140 million women and girls have undergone the practice (1). Today, female genital mutilation is defined as a violation of human rights, and in many countries (e.g., Senegal, Burkina Faso) laws have been passed to outlaw female genital mutilation. Nevertheless, female genital mutilation is still performed by many African tribes. In Senegal, about 20% of the female population is estimated to be circumcised (2).

The age of the performance (of female genital mutilation) varies across and within countries. Most of the operations occur before the end of childhood (mainly between 4 and 10 years). The medical consequences have been broadly investigated. However, there has been hardly any research to qualify and quantify the impact on psychological health. Case studies mention phobias, depression, and sexual disorders (3). Nonetheless, it has been ignored that female genital mutilation, representing a violation of someone’s physical intactness, can be classified as a psychological trauma according to DSM-IV and a potential cause of posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD). Hence, the purpose of the study was to explore the relationship between female genital mutilation and psychiatric illnesses, especially PTSD. Despite the infliction of long-lasting somatic harm on most individuals, the fact that female genital mutilation is culturally embedded may represent a protective factor against the emergence of PTSD (4). In a subsidiary analysis, we also investigated whether or not the presence of PTSD is accompanied by declarative memory dysfunctions (deficits in active recall of previously encoded information), which are often found in other traumatized groups (5).

Method

The study was conducted over a 3-month period in the springtime of 2003 in the capital of Senegal, Dakar. A group of 47 Senegalese women were interviewed in French by one of the authors (A.B.). Before the interviews, the researcher spent some time, usually about 2 days, establishing a solid relationship with the participants, creating a mutual sense of trust. The purposes of the study, as well as the normal ethical standards of anonymity, were explained to the women in detail.

The groups consisted of 23 circumcised and 24 uncircumcised women. They were recruited by a nurse, private contacts, and after the start of the survey, by former participants. Exclusion criteria were neurological disorders, psychotic disorders, current substance dependence, circumcision before the age of 5, and a lack of language skills (French). The participants’ ages ranged from 15 to 40 years, averaging 22.9 years (SD=4.2). In terms of education, the average was 11.5 years (SD=2.3). Twenty-one percent of the subjects were married, and 79% were single. More than 80% of the entire group had already faced traumatic life experiences. The most often named traumatic life event was the sudden death of a friend or a family member, which 66% of the participants had already witnessed. The two groups of circumcised and uncircumcised women did not differ significantly in terms of age, education, marital status, or traumatic life experiences. The age of circumcision ranged between 5 and 14 years; the mean was 8.2 years (SD=2.7). In none of the cases were local analgesics or narcotics used.

A semistructured interview was performed comprising questions about demographic variables and questions concerning the event of circumcision and the subjects’ feelings toward it. The diagnostic interview in this study was the Mini International Neuropsychiatric Interview (6), a short structured interview that showed good reliability and validity compared to the Composite International Diagnostic Interview and to the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV (7). Furthermore, a short form of the Traumatic Life Event Questionnaire (E.S. Kubany, unpublished, 1995) was used to assess other traumatic life experiences. Short-term and long-term memory were measured with the Rey Figure Test (8).

Results

All but one circumcised participant remembered the day of her circumcision as extremely appalling and traumatizing. Over 90% of the women described feelings of intense fear, helplessness, horror, and severe pain, and over 80% were still suffering from intrusive reexperiences of their circumcision. For 78% of the subjects, the event was performed unexpectedly and without any preliminary explanation. The psychiatric diagnoses based on the Mini International Neuropsychiatric Interview are presented in Table 1 for circumcised and uncircumcised women. Almost 80% of the circumcised women met criteria for affective or anxiety disorders. PTSD was particularly highly presented (30.4%). In the group of uncircumcised women, only one subject fulfilled the diagnostic criteria for an affective disorder.

In the copy trial of the Rey Figure Test, no differences among the three groups appeared. However, in both the immediate and delayed trials, participants with PTSD performed significantly worse than the circumcised women without PTSD and the uncircumcised women (immediate recall: F=5.31, df=2, 43, p≤0.01; with Bonferroni correction: participants with PTSD > circumcised women without PTSD (p≤0.05), uncircumcised women (p≤0.01); delayed recall: F=4.73, df=2, 43, p≤0.01; with Bonferroni correction: participants with PTSD > circumcised women without PTSD (p≤0.05), uncircumcised women (p≤0.01). Circumcised women without PTSD and uncircumcised women were indistinguishable in both parameters.

Discussion

The results of this study indicated that female genital mutilation is likely to cause various emotional disturbances, forging the way to psychiatric disorders, especially PTSD. The high rate of PTSD of more than 30% in this group is comparable to the rate of PTSD of early childhood abuse, which, on average, ranges between 30% and 50% (9). Despite the fact that female genital mutilation presents a part of the participants’ ethnic background, the results imply that cultural embedment does not protect against the development of PTSD and other psychiatric disorders. In agreement with other studies (5), PTSD rather than trauma was associated with declarative memory dysfunction.

Although the results of this study support the claim that female genital mutilation exerts a major negative impact on mental health beyond somatic complications, some caution is warranted in interpreting these results. The small group size presents an important limitation, and the results do not allow general conclusions about the prevalence of psychiatric disorders after female genital mutilation. The composition characteristics of the group (i.e., the low age and the high level of education) might also have an influence on the findings of this study. The attempt to interview women with lower education levels with a female interpreter did not work out because of the sensitive subject and the highly secret nature of female genital mutilation.

Moreover, the low prevalence of female genital mutilation in Senegal may be important for the occurrence of psychiatric disorders, possibly representing another risk factor for the establishment of PTSD. Since only 20% of the female population have undergone female genital mutilation, the circumcised women are often aware that their status is not generally accepted in society. Even more, in schools and other public facilities, people are increasingly taught about the negative effects, creating an atmosphere against female genital mutilation (2). As a consequence, the assimilation of the trauma may be different from other African countries where circumcision is more widespread. Of course, many other factors, such as coping style, other traumatic experiences, information before circumcision, and sexual experiences, may also play an important role in mental health outcome. Nevertheless, this study provides an additional strong argument for the provision of culturally grounded knowledge that can contribute to the eradication of female genital mutilation. In the spirit of the expanding role of psychiatrists and psychologists in documenting human rights abuses, it is of great importance to continue the research and to support women suffering from emotional difficulties. The alarmingly high rates of psychiatric disturbance among this group of circumcised women provide important evidence that researchers, as well as clinicians, have an obligation to focus more attention on the urgent needs of circumcised women.

|

Received March 18, 2004; revisions received April 13, 2004, and July 4, 2004; accepted July 28, 2004. From the University Hospital Hamburg–Eppendorf, Germany; and the Clinical Neuropsychology Unit, Hospital for Psychiatry and Psychotherapy. Address correspondence and reprint requests to Dr. Moritz, Clinical Neuropsychology Unit, Hospital for Psychiatry and Psychotherapy, Martinistraße 52, 20246 Hamburg, Germany; [email protected] (e-mail). The authors thank Rouguyatou Niang, Fatou Mata Hanne, Fousseni Nassakou, Prof. Dr. Naber, Dr. Frauke Teegen, Prof. Dr. Bernhard Dahme, Emily Page, Lena Jelinek, and Florentine Larbig.

1. World Health Organization: Female Genital Mutilation: Integrating the Prevention and the Management of the Health Complications Into the Curricula of Nursing and Midwifery: A Student’s Manual. Geneva, WHO, 2001, pp 25–27Google Scholar

2. Kessler Bodiang C, Eppel G, Guèye AS: [Female Circumcision in the Area of Kolda in Senegal: Perceptions, Attitudes, and Practices.] Ziguinchor, Senegal, Gesellschaft für technische Zusammenarbeit (GTZ), 2001 (French)Google Scholar

3. Lightfoot-Klein H: Secret Wounds. Bloomington, Ind, First Books (Authorhouse), 2003Google Scholar

4. Fontana A, Rosenheck R: Traumatic war stressors and psychiatric symptoms among World War II, Korean, and Vietnam War veterans. Psychol Aging 1994; 9:27–33Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

5. Golier J, Yehuda R: Neuropsychological processes in post-traumatic stress disorder. Psychiatr Clin North Am 2002; 25:295–315Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

6. Sheehan DV, Lecrubier Y, Sheehan KH, Janavs J, Weiller E, Keskiner A, Schinka J, Knapp E, Sheehan MF, Dunbar GC: The validity of the Mini International Neuropsychiatric Interview (MINI) according to the SCID-P and its reliability. Eur Psychiatry 1997; 12:232–241Crossref, Google Scholar

7. Sheehan DV, Lecrubier Y, Sheehan KH, Amorim P, Janavs J, Weiller E, Hergueta T, Baker R, Dunbar GC: The Mini-International Neuropsychiatric Interview (MINI): the development and validation of a structured diagnostic psychiatric interview for DSM-IV and ICD-10. J Clin Psychiatry 1998; 59(suppl 20):22–33Google Scholar

8. Lezak MD: Neuropsychological Assessment, vol 3. Oxford, UK, Oxford University Press, 1995Google Scholar

9. Kessler RC, Sonnega A, Bromet E, Hughes M, Nelson CB: Posttraumatic stress disorder in the National Comorbidity Survey. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1995; 52:1048–1060Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar